As the trade war heightens US-China tensions, distrust of Chinese-American scientists and experts is prompting unfounded FBI investigations, intimidation and harassment

Peter Waldman 31 Jan, 2020

As the trade war heightens US-China tensions, distrust of Chinese-American scientists and experts is prompting unfounded FBI investigations, intimidation and harassmen

For days after his FBI interrogation, Wei Su wondered: where had the microphone been? The agents had played him a scratchy recording of a conversation he’d had with a friend at a restaurant in Eatontown, New Jersey. Both men found it strange when an unasked-for pot of hot tea arrived at their table, but only later did Su, an award-winning scientist for the United States Army’s Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate, form a hypothesis. He thinks the teapot was bugged.

On the recording, Su says, he can be heard telling his friend in Chinese to always use English when they spoke on the phone because the government was monitoring his calls. “When you work with us, you need to be careful,” he warned. Su says the FBI demanded to know if “us” was a reference to Chinese intelligence. No, he answered, “us” simply meant his employer, the army.

Nevertheless, questions about Su’s loyalty would propel a multi-year investigation that, in 2016, prompted the US Department of Defence to revoke the top-secret security clearance he’d held for 24 years. He retired the next year: humiliated, angry and, the Pentagon later admitted, completely innocent.

The short, bespectacled scientist, who loves to kayak, garden and play the piano, now divides his time between Maryland and Florida with his wife of 32 years, Elaine, a retired branch chief for a different army communications lab. The government’s case against him amounted to a tempest in a teapot, Su says, if not a listening device as well.

Some of my clients won’t even call or visit their own mother in China to avoid having to disclose the ‘foreign contact’

Alan Edmunds, lawyer

Su’s ordeal reflects how the US government’s distrust of China, which flared during the Obama administration and has erupted openly during President Donald Trump’s trade war, has mutated into distrust of Chinese-Americans. Signs of this heightened scrutiny emerged last July when FBI director Christopher Wray told the Senate Judiciary Committee that the bureau was investigating more than 1,000 cases of attempted theft of US intellectual property, with “almost all” leading back to China.

Last year the US National Institutes of Health, working with the FBI, started probes into about 180 researchers at more than 70 hospitals and universities, seeking undisclosed ties to China. Some suspected scientists were instructed by their associates in China to conceal their connections to the country, says Ross McKinney, chief scientific officer for the Association of American Medical Colleges. “The presumption of trust is blown by the fact that there’s a systematic approach to lying,” he says.

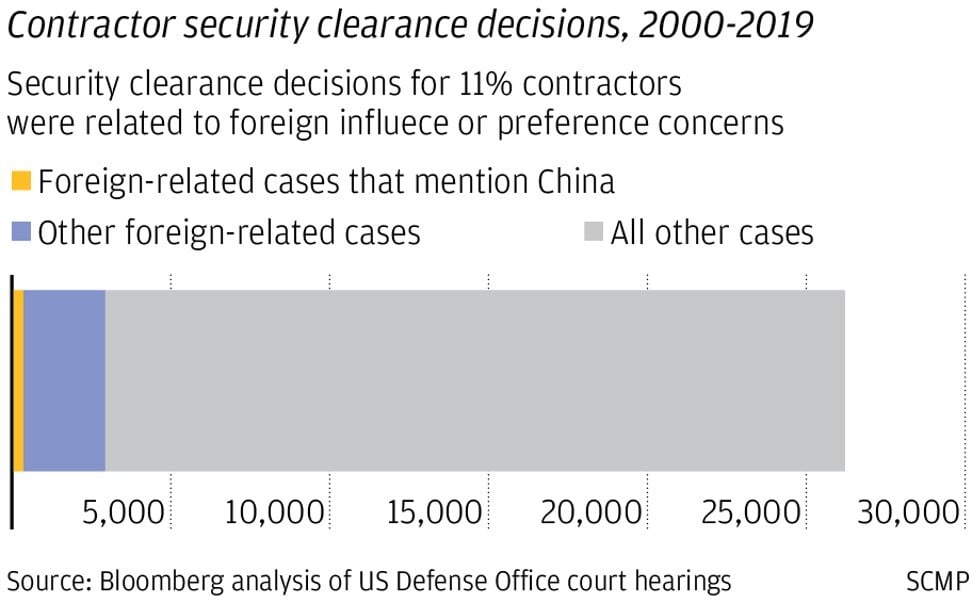

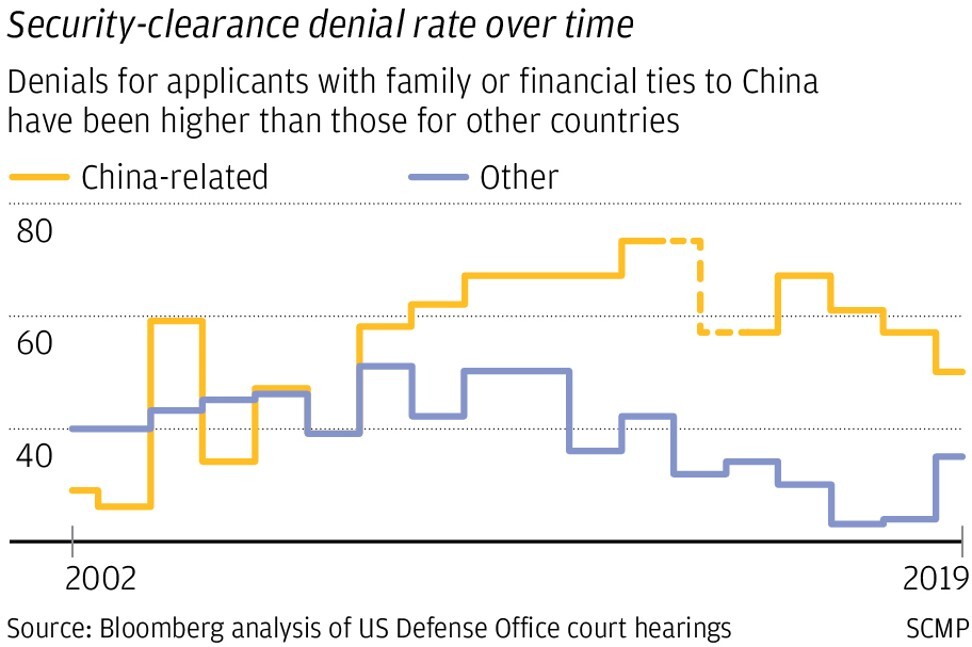

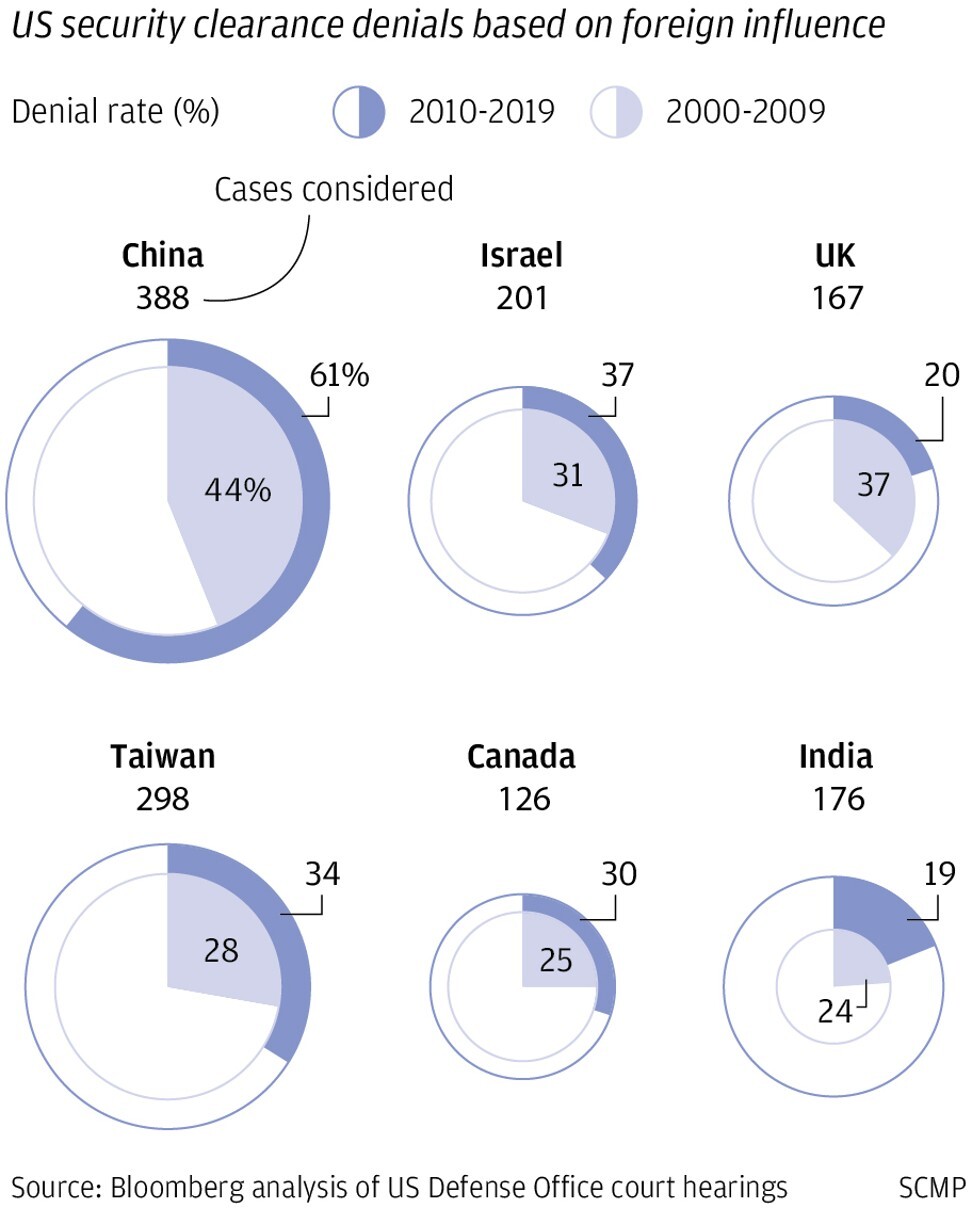

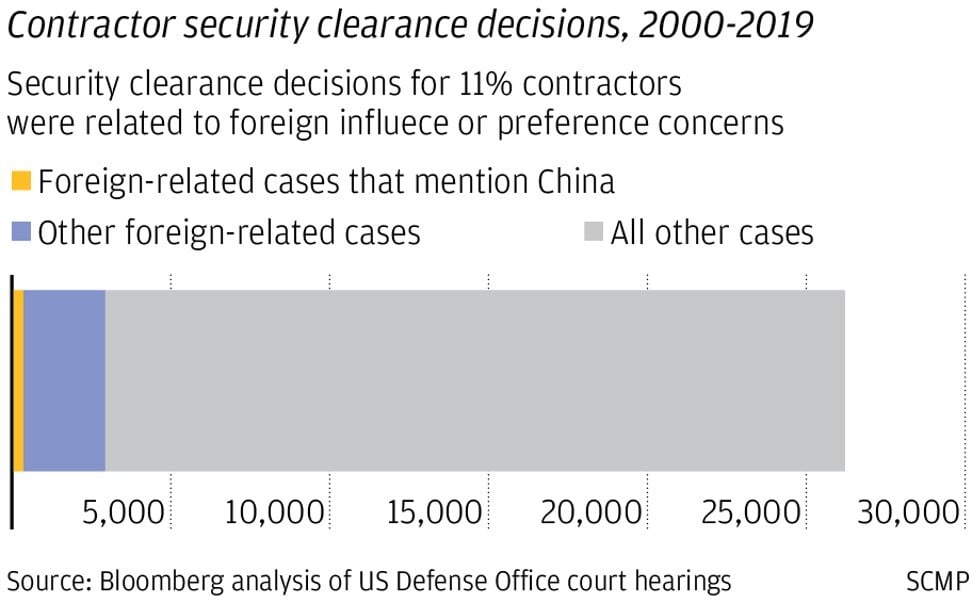

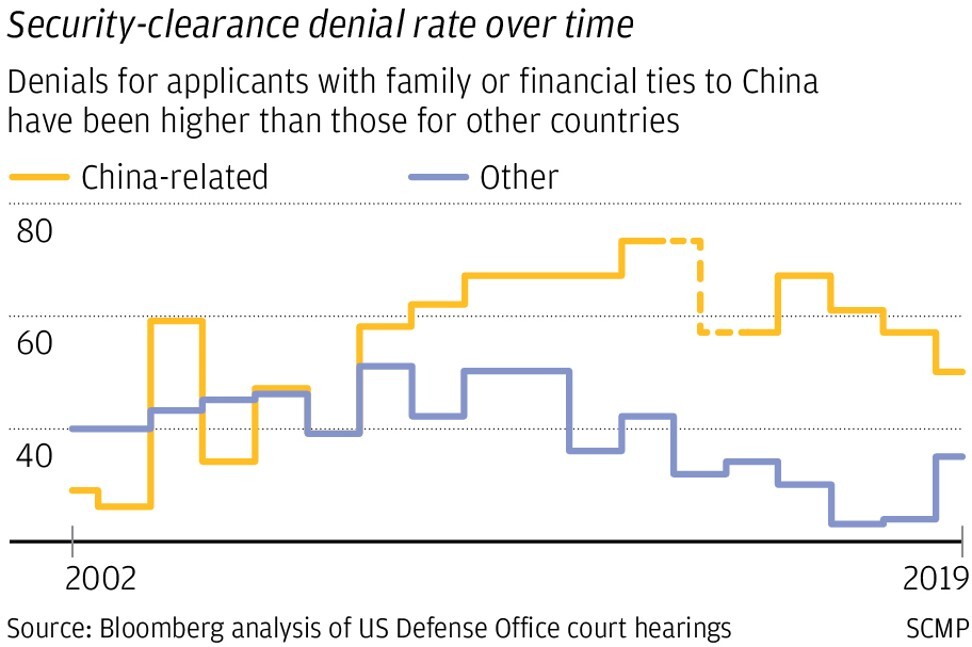

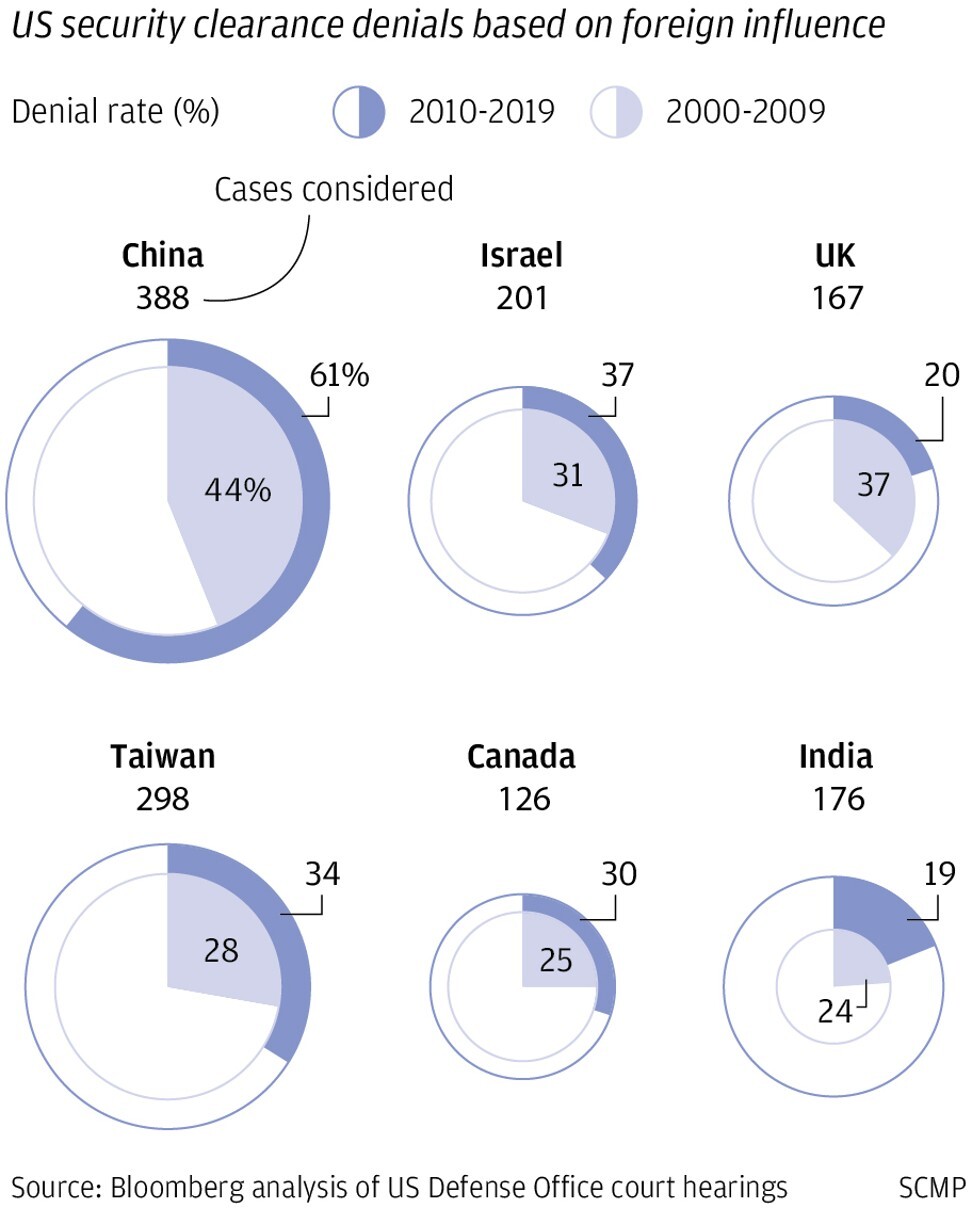

A Bloomberg News analysis of more than 26,000 security-clearance decisions for federal contractors since 1996 demonstrates another facet of the government’s steep loss of faith in Americans with ties to China. From 2000 to 2009, clearance applicants with connections to China – such as family or financial relationships – were denied Pentagon clearances at the same rate as applicants with links to all other countries: 44 per cent. But from 2010 to October 31, 2019, the China-related denial rate jumped to 61 per cent, and the rate for all other countries fell to 34 per cent.

‘Extreme flight risk’: Zhang Yujing, Chinese woman arrested at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago club, owns US$1.3 million home and BMW, court told

Chinese woman arrested at Mar-a-Lago ‘owns US$1.3 million home, BMW’

US academics condemn ‘racial profiling’ of Chinese students and scholars over spying fears

Top Chinese intelligence agency, former EU ambassador embroiled in German spy investigation

Even people with ties to Iran and Russia, among the most often rebuffed applicants in the early 2000s with denial rates of 64 per cent and 52 per cent, respectively, have had their rejection rates fall since 2010, to 48 per cent and 45 per cent. That compares with a 17-point jump in the rate of China-linked denials. Some lawyers who specialise in helping applicants get security clearances say they won’t accept Chinese-American clients any more for fear of wasting their money.

“It’s gotten to the point that some of my clients won’t even call or visit their own mother in China to avoid having to disclose the ‘foreign contact’,” says Alan Edmunds, who has practised national-security law for 41 years. “I’ve never seen the DOD [Department of Defence], or other three-letter agencies, in such a heightened state of sensitivity.”

Cynthia McGovern, spokeswoman for the Defence Counterintelligence and Security Agency, said in an email that the department doesn’t comment on specific cases, but that adjudicators “strive to ensure each individual case is decided based on all relevant information and in the best interest of national security”.

Su’s case tracks the rising alarm – and alarmism – over the past decade. Su, 67, earned his undergraduate degree in China and his doctorate in electrical engineering at City University of New York in 1992. From 1994 until he retired, he worked at the army’s Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate, known as I2WD, a stealthy lab that develops electronic warfare systems to enable military forces to communicate and eavesdrop without enemy interference.

An elected fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Su has 170 scientific papers and 35 patents in his name. His mentor and frequent collaborator, I2WD’s former chief scientist John Kosinski, wrote in a 2015 job recommendation that Su had achieved “an almost unheard-of distinction: his personally developed, army-owned software product was adopted for use within certain offices of the [National Security Agency]”.

In 2011, after 17 years of routine, periodic reviews of his security clearance, Su started receiving frequent visitors to his office from the FBI and US military intelligence. Eventually, he says, they demanded he confess to spying for China lest he end up “like the Rosenbergs”. When Su insisted he was a loyal American, FBI agents placed him under surveillance and threatened to have a Swat team arrest him in his home in front of his family, he says. “It was an opportunity to catch a big fish and make their careers,” says Su.

Too often, distrust of people of Chinese heritage drives decision-making at the FBI and other US security agencies, according to interviews with more than a dozen people who have worked as federal investigators. One of them, Mike German, worked as an FBI special agent from 1988 to 2004. In his book, Disrupt, Discredit, and Divide (2019), he argues that FBI leaders have propagated Chinese and other ethnic stereotypes since September 11 as part of an effort to focus more heavily on domestic counter-intelligence.

In 2005, the bureau introduced an initiative that used US census data to map US neighbourhoods by race and ethnicity and guide FBI surveillance of potential terrorists and spies, German wrote. In 2009, the bureau justified opening such an assessment of Chinese communities in San Francisco on the grounds that organised crime had existed “for generations” in the city’s Chinatown, according to an FBI memo obtained in 2011 by the American Civil Liberties Union.

FBI internal training materials released at the same time featured presentations on “The Chinese”, which were full of generalisations about Confucian relationships (“authority and subordination is accepted”) and the concept of saving face.

“The training is a form of othering, which is a dangerous thing to do to a national security workforce learning to identify the dangerous ‘them’ they’re supposed to protect ‘us’ from,” says German, now a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, at New York University Law School. “Even the title, ‘The Chinese’, imagines 1.4 billion people sharing the same characteristics. It seems more likely to implant bias than to educate agents about the complex behaviour of spies.”

LaRae Quy, who worked as an FBI counter-intelligence agent for 24 years before retiring in 2006, believes the generalisations are justified. People from China, unlike Russians, maintain close ties to their homeland that make them particularly vulnerable to recruiting as spies by Chinese intelligence, she says. “You’re American-born, but you’re Chinese at heart,” says Quy, who is now an author and executive consultant.

When people who want to work for the DOD, either as contractors or employees, are denied security clearances, they can ask the Pentagon’s Defence Office of Hearings and Appeals (DOHA) for an administrative review. DOHA’s decisions regarding employees, such as Su, are kept private. But the agency publishes its decisions on contractors, with names of applicants and witnesses redacted.

DOHA judges apply 13 federal guidelines to determine trustworthiness. Most are common sense, such as an applicant’s drug and criminal history, or whether any debts could motivate the sale of secrets. They also consider each country’s espionage risk by two key guidelines, “foreign influence” and “foreign preference”, which in essence ask whether applicants have friends, family, property or other foreign ties that could compromise their loyalty to the US. Federal law stipulates the benefit of the doubt lies with the government: “Any doubt concerning personnel being considered for access to classified information will be resolved in favour of the national security.”

In a representative DOHA decision in 2018, the 61-year-old founder of a machinery-design company sought security clearance to work on his company’s defence contracts. He emigrated from China to the US in 1985, earned a doctorate, became an American citizen, and has two grown daughters born in the US. He also has real estate, retirement accounts and substantial financial interests in the US, wrote DOHA judge Noreen Lynch.

She noted “no evidence” he or his father and two sisters in China were approached for sensitive information by Chinese intelligence agents. And though the businessman used to visit and send money to his 90-year-old father annually, he stopped a few years ago as a result of his security-clearance investigation.

Siding with the Pentagon, Lynch took “administrative notice” of a US finding that China and Russia are “the most aggressive” sponsors of economic spying. She wrote: “Applicant’s close relationship to his father and sisters, who are vulnerable to potential Chinese coercion, outweighs his connections to the United States.” Clearance denied.

The idea that having friends or family in China makes Chinese-Americans vulnerable to coercion by Chinese agents, directly or through their loved ones, is a premise of most of DOHA’s China-linked denials. In Lynch’s 12-page ruling, the word “coercion” appears 11 times.

In the cross hairs: US accuses Chinese-American scientists of spying

5 May 2018

National-security lawyers question that notion. “I dare say you will find no evidence of this threat being real. Logical? Yes. Real? No,” says Mark Zaid, who represents numerous security-clearance applicants. (He’s also co-counsel for the Ukraine whistle-blower.)

The coercion concept is a holdover from the Cold War, when Soviet-bloc governments blackmailed their own citizens to get family members to spy for communist regimes, according to a 2017 report published by the Pentagon’s Defence Personnel and Security Research Centre.

“Threatening to harm a person’s relatives living under Communist control in Eastern Europe, or threatening to publicly reveal one’s sexual identity, have not been effective coercion strategies” since the fall of the Berlin Wall, wrote the report’s author, Katherine Herbig, of Northrop Grumman Technology Services.

Of the 141 US convictions for espionage and related crimes from 1980 to 2015 – 22 of them involving China – coercion was not a “strong motivation” in a single case, says the report. And at least 12 of the 22 people convicted of spying for China were not ethnic Chinese, according to Jeremy Wu, a retired federal official who analysed China espionage cases for an academic research paper.

For army engineer Wei Su the trouble began in 2011, when he was approached by a stranger at his hotel while attending a technical conference in Auckland, New Zealand. The man said he was with Taiwanese intelligence and asked Su if he had given information to China. Su brushed him off and reported the incident immediately to his supervisor in Maryland.

When he returned to the US, he says, a military intelligence agent told him he must have done something wrong to warrant the “foreigner’s” approach and urged Su to confess. Su says he has never had any improper contact with any Chinese official.

Over the next 21 months, Su endured six aggressive interrogation sessions, alternating between military intelligence agents and the FBI. They pressured Su to admit to working for China, which he steadfastly denied. They accused him of inventing a technology for embedding digital watermarks in DVDs not for the commercial purpose of protecting intellectual property, as stated in his research, but rather to spirit secrets to China. They said a friend of Su’s told them Su had contacted Chinese officials while visiting his dying father in China, in 2007. A lie, Su says.

In an email, FBI spokeswoman Carol Cratty says the bureau does not comment on specific cases nor does it “initiate investigations based on an individual’s race, ethnicity, national origin or religion”.

According to Su, FBI agents threatened to knock down his door and arrest him at 5am, and hound him until his health gave out. They asked his relatives, friends and neighbours if he was a spy, Su says, after which many stopped talking to him. He says interrogators from military intelligence warned him multiple times that the punishment for espionage was the electric chair. (The federal government hasn’t used the chair for executions since 1957.) They asked, again and again, “Why would you work for the US government when you can get a great job in private industry?” He told them the army scientists who recruited him had convinced him a government lab offered the best opportunities to do advanced research.

Su says the FBI believed he was slipping secrets to Mengchu Zhou, an engineering professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, in Newark, who would pass them on to the Chinese consulate in New York. At the time, Su was running a government contract with Zhou to do unclassified research on decoding signals.

Zhou says the FBI questioned him more than 10 times about Su, as well as about his own frequent social and professional contacts with delegations and diplomats from China. “They were trying to establish a link between Wei Su, me and the consulate,” Zhou says.

I sat across the table from my boss, who was a two-star general, scratching our heads on this

Henry Muller Jnr

The FBI put him on a polygraph, Zhou says, and repeatedly asked a single question: “Is Wei Su a spy?” He flunked, they told him, but agents refused to show Zhou his wave graph. “They wanted to scare me into telling them Wei Su was a spy but, of course, it wasn’t true,” Zhou says.

Zhou thinks the FBI was tapping his phone when he and Su agreed to meet for dinner in 2011 at the now-closed Sawa Hibachi Steakhouse & Sushi Bar, near the Jersey Shore, a meal both men remember for the now-suspect teapot. Su says the FBI agents seemed sure they had a smoking gun after that night.

And yet, after they confronted Su, investigators seemed to back off. Zhou still had to endure multi-hour delays when returning from overseas, as immigration agents searched his electronic devices, he says.

Su says he heard nothing from investigators for 2½ years. Then, in 2015, he was notified by his boss, Henry Muller Jnr, that his security clearance had been suspended because of new “counter-intelligence information”. Muller, now retired, says he wanted Su to take on a senior technical position once his security clearance was sorted out. But no one at military intelligence would say what the new information was. “I sat across the table from my boss, who was a two-star general, scratching our heads on this,” Muller says. “It seemed very nebulous at the time. But that’s the way these security guys work. There’s nothing you can do about it.”

It took 13 months for the Pentagon to issue Su a “statement of reason” for his clearance suspension. The classified memo rehashed settled questions from Su’s background investigations in 1997, 2002 and 2010, he says. It accused him of enjoying “unexplained affluence” and asked how his family took five holidays in 10 years on a household income of US$270,000 a year, according to Su’s rebuttal documents.

The memo questioned whether he had received undisclosed funds from China to pay off a mortgage in 2009, two years after visiting the country, and whether a US$34,000 deposit in Su’s account came from “financially profitable criminal acts”. It also accused Su of concealing contacts with two former classmates from China.

Su responded to the allegations line by line. His family holidays to Europe, Southeast Asia, Mexico and China were budget tours that came to about US$150 a day per person. He documented all his paid-off debts and explained that the US$34,000 deposit was a US government cheque to compensate military homeowners when the army closed Fort Monmouth, in New Jersey, and moved Su’s command to Maryland’s Aberdeen Proving Ground. He enclosed affidavits from past background investigations to prove he had properly disclosed his contacts with Chinese friends.

Six months later, in October 2016, the Pentagon sent a “letter of revocation” cancelling his clearance. The final notice dropped the financial allegations but claimed Su failed to fully disclose his classmate contacts in the early 2000s, even after an investigator had put him on “explicit notice” in 2004 that he had to disclose them. After the revocation, Su continued to work on unclassified research, while fighting to clear his name with arbiters at the Pentagon’s Consolidated Adjudications Facility, known as the CAF.

In November 2017, he got a break. The federal Office of Personnel Management, which handled his background investigations for security clearances, agreed to correct several misstatements in the investigators’ 2004 and 2010 reports to show he had appropriately disclosed his classmate contacts. Su sent the corrections to the CAF and retired from the army at the end of 2017.

In May 2018 he received a short letter from the CAF. Based on the corrected record, it said, the Pentagon’s previous letters suspending and revoking Su’s security clearance “are not accurate and are hereby rescinded”.

“Even now, it’s like a nightmare,” Su says. “The investigators didn’t realise Chinese-Americans are Americans, not Chinese.”

Text: Bloomberg BusinessWeek

Data analysis by Andre Tartar

For days after his FBI interrogation, Wei Su wondered: where had the microphone been? The agents had played him a scratchy recording of a conversation he’d had with a friend at a restaurant in Eatontown, New Jersey. Both men found it strange when an unasked-for pot of hot tea arrived at their table, but only later did Su, an award-winning scientist for the United States Army’s Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate, form a hypothesis. He thinks the teapot was bugged.

On the recording, Su says, he can be heard telling his friend in Chinese to always use English when they spoke on the phone because the government was monitoring his calls. “When you work with us, you need to be careful,” he warned. Su says the FBI demanded to know if “us” was a reference to Chinese intelligence. No, he answered, “us” simply meant his employer, the army.

Nevertheless, questions about Su’s loyalty would propel a multi-year investigation that, in 2016, prompted the US Department of Defence to revoke the top-secret security clearance he’d held for 24 years. He retired the next year: humiliated, angry and, the Pentagon later admitted, completely innocent.

The short, bespectacled scientist, who loves to kayak, garden and play the piano, now divides his time between Maryland and Florida with his wife of 32 years, Elaine, a retired branch chief for a different army communications lab. The government’s case against him amounted to a tempest in a teapot, Su says, if not a listening device as well.

Some of my clients won’t even call or visit their own mother in China to avoid having to disclose the ‘foreign contact’Alan Edmunds, lawyer

Su’s ordeal reflects how the US government’s distrust of China, which flared during the Obama administration and has erupted openly during

President Donald Trump’s trade war, has mutated into distrust of Chinese-Americans. Signs of this heightened scrutiny emerged last July when

FBI director Christopher Wray told the Senate Judiciary Committee that the bureau was investigating more than 1,000 cases of attempted theft of US intellectual property, with “almost all” leading back to China.

Last year the US National Institutes of Health, working with the FBI, started probes into about 180 researchers at more than 70 hospitals and universities, seeking undisclosed ties to China. Some suspected scientists were instructed by their associates in China to conceal their connections to the country, says Ross McKinney, chief scientific officer for the Association of American Medical Colleges. “The presumption of trust is blown by the fact that there’s a systematic approach to lying,” he says.

A Bloomberg News analysis of more than 26,000 security-clearance decisions for federal contractors since 1996 demonstrates another facet of the government’s steep loss of faith in Americans with ties to China. From 2000 to 2009, clearance applicants with connections to China – such as family or financial relationships – were denied Pentagon clearances at the same rate as applicants with links to all other countries: 44 per cent. But from 2010 to October 31, 2019, the China-related denial rate jumped to 61 per cent, and the rate for all other countries fell to 34 per cent.

In other words, more than three-fifths of applicants who have ties to China are rejected for security clearances to work for government contractors, while two-thirds of applicants with ties to other countries are approved.

US academics condemn ‘racial profiling’ of Chinese students over spying fears

Even people with ties to Iran and Russia, among the most often rebuffed applicants in the early 2000s with denial rates of 64 per cent and 52 per cent, respectively, have had their rejection rates fall since 2010, to 48 per cent and 45 per cent. That compares with a 17-point jump in the rate of China-linked denials. Some lawyers who specialise in helping applicants get security clearances say they won’t accept Chinese-American clients any more for fear of wasting their money.

“It’s gotten to the point that some of my clients won’t even call or visit their own mother in China to avoid having to disclose the ‘foreign contact’,” says Alan Edmunds, who has practised national-security law for 41 years. “I’ve never seen the DOD [Department of Defence], or other three-letter agencies, in such a heightened state of sensitivity.”

Cynthia McGovern, spokeswoman for the Defence Counterintelligence and Security Agency, said in an email that the department doesn’t comment on specific cases, but that adjudicators “strive to ensure each individual case is decided based on all relevant information and in the best interest of national security”.

Su’s case tracks the rising alarm – and alarmism – over the past decade. Su, 67, earned his undergraduate degree in China and his doctorate in electrical engineering at City University of New York in 1992. From 1994 until he retired, he worked at the army’s Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate, known as I2WD, a stealthy lab that develops electronic warfare systems to enable military forces to communicate and eavesdrop without enemy interference.

An elected fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Su has 170 scientific papers and 35 patents in his name. His mentor and frequent collaborator, I2WD’s former chief scientist John Kosinski, wrote in a 2015 job recommendation that Su had achieved “an almost unheard-of distinction: his personally developed, army-owned software product was adopted for use within certain offices of the [National Security Agency]”.

In 2011, after 17 years of routine, periodic reviews of his security clearance, Su started receiving frequent visitors to his office from the FBI and US military intelligence. Eventually, he says, they demanded he confess to spying for China lest he end up “like the Rosenbergs”. When Su insisted he was a loyal American, FBI agents placed him under surveillance and threatened to have a Swat team arrest him in his home in front of his family, he says. “It was an opportunity to catch a big fish and make their careers,” says Su.

Too often, distrust of people of Chinese heritage drives decision-making at the FBI and other US security agencies, according to interviews with more than a dozen people who have worked as federal investigators. One of them, Mike German, worked as an FBI special agent from 1988 to 2004. In his book, Disrupt, Discredit, and Divide (2019), he argues that FBI leaders have propagated Chinese and other ethnic stereotypes since September 11 as part of an effort to focus more heavily on domestic counter-intelligence.

FBI Director Christopher Wray. Photo: AP

In 2005, the bureau introduced an initiative that used US census data to map US neighbourhoods by race and ethnicity and guide FBI surveillance of potential terrorists and spies, German wrote. In 2009, the bureau justified opening such an assessment of Chinese communities in San Francisco on the grounds that organised crime had existed “for generations” in the city’s Chinatown, according to an FBI memo obtained in 2011 by the American Civil Liberties Union.

FBI internal training materials released at the same time featured presentations on “The Chinese”, which were full of generalisations about Confucian relationships (“authority and subordination is accepted”) and the concept of saving face.

“The training is a form of othering, which is a dangerous thing to do to a national security workforce learning to identify the dangerous ‘them’ they’re supposed to protect ‘us’ from,” says German, now a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, at New York University Law School. “Even the title, ‘The Chinese’, imagines 1.4 billion people sharing the same characteristics. It seems more likely to implant bias than to educate agents about the complex behaviour of spies.”

LaRae Quy, who worked as an FBI counter-intelligence agent for 24 years before retiring in 2006, believes the generalisations are justified. People from China, unlike Russians, maintain close ties to their homeland that make them particularly vulnerable to recruiting as spies by Chinese intelligence, she says. “You’re American-born, but you’re Chinese at heart,” says Quy, who is now an author and executive consultant.

When people who want to work for the DOD, either as contractors or employees, are denied security clearances, they can ask the Pentagon’s Defence Office of Hearings and Appeals (DOHA) for an administrative review. DOHA’s decisions regarding employees, such as Su, are kept private. But the agency publishes its decisions on contractors, with names of applicants and witnesses redacted.

DOHA judges apply 13 federal guidelines to determine trustworthiness. Most are common sense, such as an applicant’s drug and criminal history, or whether any debts could motivate the sale of secrets. They also consider each country’s espionage risk by two key guidelines, “foreign influence” and “foreign preference”, which in essence ask whether applicants have friends, family, property or other foreign ties that could compromise their loyalty to the US. Federal law stipulates the benefit of the doubt lies with the government: “Any doubt concerning personnel being considered for access to classified information will be resolved in favour of the national security.”

In a representative DOHA decision in 2018, the 61-year-old founder of a machinery-design company sought security clearance to work on his company’s defence contracts. He emigrated from China to the US in 1985, earned a doctorate, became an American citizen, and has two grown daughters born in the US. He also has real estate, retirement accounts and substantial financial interests in the US, wrote DOHA judge Noreen Lynch.

She noted “no evidence” he or his father and two sisters in China were approached for sensitive information by Chinese intelligence agents. And though the businessman used to visit and send money to his 90-year-old father annually, he stopped a few years ago as a result of his security-clearance investigation.

Siding with the Pentagon, Lynch took “administrative notice” of a US finding that China and Russia are “the most aggressive” sponsors of economic spying. She wrote: “Applicant’s close relationship to his father and sisters, who are vulnerable to potential Chinese coercion, outweighs his connections to the United States.” Clearance denied.

The idea that having friends or family in China makes Chinese-Americans vulnerable to coercion by Chinese agents, directly or through their loved ones, is a premise of most of DOHA’s China-linked denials. In Lynch’s 12-page ruling, the word “coercion” appears 11 times.

In the cross hairs: US accuses Chinese-American scientists of spying

5 May 2018

National-security lawyers question that notion. “I dare say you will find no evidence of this threat being real. Logical? Yes. Real? No,” says Mark Zaid, who represents numerous security-clearance applicants. (He’s also co-counsel for the

Ukraine whistle-blower.)

The coercion concept is a holdover from the Cold War, when Soviet-bloc governments blackmailed their own citizens to get family members to spy for communist regimes, according to a 2017 report published by the Pentagon’s Defence Personnel and Security Research Centre. “Threatening to harm a person’s relatives living under Communist control in Eastern Europe, or threatening to publicly reveal one’s sexual identity, have not been effective coercion strategies” since the fall of the Berlin Wall, wrote the report’s author, Katherine Herbig, of Northrop Grumman Technology Services.

Of the 141 US convictions for espionage and related crimes from 1980 to 2015 – 22 of them involving China – coercion was not a “strong motivation” in a single case, says the report. And at least 12 of the 22 people convicted of spying for China were not ethnic Chinese, according to Jeremy Wu, a retired federal official who analysed China espionage cases for an academic research paper.

For army engineer Wei Su the trouble began in 2011, when he was approached by a stranger at his hotel while attending a technical conference in Auckland, New Zealand. The man said he was with Taiwanese intelligence and asked Su if he had given information to China. Su brushed him off and reported the incident immediately to his supervisor in Maryland.

When he returned to the US, he says, a military intelligence agent told him he must have done something wrong to warrant the “foreigner’s” approach and urged Su to confess. Su says he has never had any improper contact with any Chinese official.

Over the next 21 months, Su endured six aggressive interrogation sessions, alternating between military intelligence agents and the FBI. They pressured Su to admit to working for China, which he steadfastly denied. They accused him of inventing a technology for embedding digital watermarks in DVDs not for the commercial purpose of protecting intellectual property, as stated in his research, but rather to spirit secrets to China. They said a friend of Su’s told them Su had contacted Chinese officials while visiting his dying father in China, in 2007. A lie, Su says.

In an email, FBI spokeswoman Carol Cratty says the bureau does not comment on specific cases nor does it “initiate investigations based on an individual’s race, ethnicity, national origin or religion”.

According to Su, FBI agents threatened to knock down his door and arrest him at 5am, and hound him until his health gave out. They asked his relatives, friends and neighbours if he was a spy, Su says, after which many stopped talking to him. He says interrogators from military intelligence warned him multiple times that the punishment for espionage was the electric chair. (The federal government hasn’t used the chair for executions since 1957.) They asked, again and again, “Why would you work for the US government when you can get a great job in private industry?” He told them the army scientists who recruited him had convinced him a government lab offered the best opportunities to do advanced research.

Su says the FBI believed he was slipping secrets to Mengchu Zhou, an engineering professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, in Newark, who would pass them on to the Chinese consulate in New York. At the time, Su was running a government contract with Zhou to do unclassified research on decoding signals.

Zhou says the FBI questioned him more than 10 times about Su, as well as about his own frequent social and professional contacts with delegations and diplomats from China. “They were trying to establish a link between Wei Su, me and the consulate,” Zhou says.

I sat across the table from my boss, who was a two-star general, scratching our heads on thisHenry Muller Jnr

The FBI put him on a polygraph, Zhou says, and repeatedly asked a single question: “Is Wei Su a spy?” He flunked, they told him, but agents refused to show Zhou his wave graph. “They wanted to scare me into telling them Wei Su was a spy but, of course, it wasn’t true,” Zhou says.

Zhou thinks the FBI was tapping his phone when he and Su agreed to meet for dinner in 2011 at the now-closed Sawa Hibachi Steakhouse & Sushi Bar, near the Jersey Shore, a meal both men remember for the now-suspect teapot. Su says the FBI agents seemed sure they had a smoking gun after that night.

And yet, after they confronted Su, investigators seemed to back off. Zhou still had to endure multi-hour delays when returning from overseas, as immigration agents searched his electronic devices, he says.

Su says he heard nothing from investigators for 2½ years. Then, in 2015, he was notified by his boss, Henry Muller Jnr, that his security clearance had been suspended because of new “counter-intelligence information”. Muller, now retired, says he wanted Su to take on a senior technical position once his security clearance was sorted out. But no one at military intelligence would say what the new information was. “I sat across the table from my boss, who was a two-star general, scratching our heads on this,” Muller says. “It seemed very nebulous at the time. But that’s the way these security guys work. There’s nothing you can do about it.”

It took 13 months for the Pentagon to issue Su a “statement of reason” for his clearance suspension. The classified memo rehashed settled questions from Su’s background investigations in 1997, 2002 and 2010, he says. It accused him of enjoying “unexplained affluence” and asked how his family took five holidays in 10 years on a household income of US$270,000 a year, according to Su’s rebuttal documents.

The memo questioned whether he had received undisclosed funds from China to pay off a mortgage in 2009, two years after visiting the country, and whether a US$34,000 deposit in Su’s account came from “financially profitable criminal acts”. It also accused Su of concealing contacts with two former classmates from China.

Su’s boss, Henry Muller Jnr.

Su responded to the allegations line by line. His family holidays to Europe, Southeast Asia, Mexico and China were budget tours that came to about US$150 a day per person. He documented all his paid-off debts and explained that the US$34,000 deposit was a US government cheque to compensate military homeowners when the army closed Fort Monmouth, in New Jersey, and moved Su’s command to Maryland’s Aberdeen Proving Ground. He enclosed affidavits from past background investigations to prove he had properly disclosed his contacts with Chinese friends.

Six months later, in October 2016, the Pentagon sent a “letter of revocation” cancelling his clearance. The final notice dropped the financial allegations but claimed Su failed to fully disclose his classmate contacts in the early 2000s, even after an investigator had put him on “explicit notice” in 2004 that he had to disclose them. After the revocation, Su continued to work on unclassified research, while fighting to clear his name with arbiters at the Pentagon’s Consolidated Adjudications Facility, known as the CAF.

In November 2017, he got a break. The federal Office of Personnel Management, which handled his background investigations for security clearances, agreed to correct several misstatements in the investigators’ 2004 and 2010 reports to show he had appropriately disclosed his classmate contacts. Su sent the corrections to the CAF and retired from the army at the end of 2017.

In May 2018 he received a short letter from the CAF. Based on the corrected record, it said, the Pentagon’s previous letters suspending and revoking Su’s security clearance “are not accurate and are hereby rescinded”.

“Even now, it’s like a nightmare,” Su says. “The investigators didn’t realise Chinese-Americans are Americans, not Chinese.”

Text: Bloomberg BusinessWeek

Data analysis by Andre Tartar