TODAY IN HISTORY FEBRUARY 13, 1945

‘The Most-Fearful Nightmare’:

75 Years After The (FIRE) Bombing Of Dresden

In the final winter of World War II, allied bombers

reduced one of Germany’s most elegant cities to

rubble, killing tens of thousands (CIVILIANS) and

sparking a bitter debate over whether the attack

was justified.

(NO! IT WAS AND IS A WAR CRIME)

A British Royal Air Force memo to pilots also noted the bombing

would incidentally “show the Russians when they arrive what

Bomber Command can do.”

EVEN BEFORE THE OFFICIAL START OF THE COLD WAR

THE ALLIES WERE PREPARED TO MARCH ON RUSSIA

A store in the ruins in late 1945 selling toiletries and beauty products,

as well as fertilizer and house paint.

People started to clear away the rubble in 1952.

People started to clear away the rubble in 1952.

SEVEN YEARS AFTER THE BOMBING AND END OF WWII

Many of Dresden’s architectural treasures were rebuilt using historical

photographs, as well as chunks of carved stone rescued from the rubble for reference.

at Dresden in 1945?

JOHN WEAR • MARCH 24, 2019

Introduction

The bombing of Dresden remains one of the deadliest and morally most-problematic raids of World War II. Three factors make the bombing of Dresden unique: 1) a huge firestorm developed that engulfed much of the city; 2) the firestorm engulfed a population swollen by refugees; and 3) defenses and shelters even for the original Dresden population were minimal.[1] The result was a high death toll and the destruction of one of Europe’s most beautiful and cultural cities.

Many conflicting estimates have been made concerning the number of deaths during the raids of Dresden on February 13-14, 1945. Historian Richard J. Evans estimates that approximately 25,000 people died during these bombings.[2] Frederick Taylor estimates that from 25,000 to 40,000 people died as a result of the Dresden bombings.[3] A distinguished commission of German historians titled “Dresden Commission of Historians for the Ascertainment of the Number of Victims of the Air Raids on the City of Dresden on 13/14 February 1945” estimates the likely death toll in Dresden at around 18,000 and definitely not more than 25,000.[4] This later estimate is considered authoritative by many sources.READ ON THIS IS A CONSPIRACY THEORY/ALT HISTORY/MUCKRAKING SITE

BUT THIS IS SOURCED ARTICLE, FROM THE RIGHT USES DISGRACED

HOLOCAUST DENIAL SOURCES SUCH AS DAVID IRVING

RAF heavy bombers are seen dropping bombs over Dresden, Germany toward

the end of World War II in this remarkable archive footage from 1945.

Introduction

The bombing of Dresden remains one of the deadliest and morally most-problematic raids of World War II. Three factors make the bombing of Dresden unique: 1) a huge firestorm developed that engulfed much of the city; 2) the firestorm engulfed a population swollen by refugees; and 3) defenses and shelters even for the original Dresden population were minimal.[1] The result was a high death toll and the destruction of one of Europe’s most beautiful and cultural cities.

Many conflicting estimates have been made concerning the number of deaths during the raids of Dresden on February 13-14, 1945. Historian Richard J. Evans estimates that approximately 25,000 people died during these bombings.[2] Frederick Taylor estimates that from 25,000 to 40,000 people died as a result of the Dresden bombings.[3] A distinguished commission of German historians titled “Dresden Commission of Historians for the Ascertainment of the Number of Victims of the Air Raids on the City of Dresden on 13/14 February 1945” estimates the likely death toll in Dresden at around 18,000 and definitely not more than 25,000.[4] This later estimate is considered authoritative by many sources.READ ON THIS IS A CONSPIRACY THEORY/ALT HISTORY/MUCKRAKING SITE

BUT THIS IS SOURCED ARTICLE, FROM THE RIGHT USES DISGRACED

HOLOCAUST DENIAL SOURCES SUCH AS DAVID IRVING

RAF heavy bombers are seen dropping bombs over Dresden, Germany toward

the end of World War II in this remarkable archive footage from 1945.

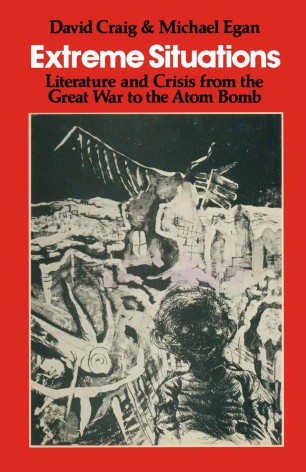

Slaughterhouse Five Or The Children's Crusade

by Kurt Vonnegut

Publication date 1969-01-01

Publication date 1969-01-01

Topics fiction

Collection opensource

Language English

Kurt Vonnegut's absurdist classic Slaughterhouse-Five introduces us to Billy Pilgrim, a man who becomes unstuck in time after he is abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore. In a plot-scrambling display of virtuosity, we follow Pilgrim simultaneously through all phases of his life, concentrating on his (and Vonnegut's) shattering experience as an American prisoner of war who witnesses the firebombing of Dresden.

Don't let the ease of reading fool you--Vonnegut's isn't a conventional, or simple, novel. He writes, "There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick, and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces. One of the main effects of war, after all, is that people are discouraged from being characters..." Slaughterhouse-Five (taken from the name of the building where the POWs were held) is not only Vonnegut's most powerful book, it is as important as any written since 1945. Like Catch- 22, it fashions the author's experiences in the Second World War into an eloquent and deeply funny plea against butchery in the service of authority. Slaughterhouse-Five boasts the same imagination, humanity, and gleeful appreciation of the absurd found in Vonnegut's other works, but the book's basis in rock-hard, tragic fact gives it a unique poignancy--and humor.

Kurt Vonnegut's absurdist classic Slaughterhouse-Five introduces us to Billy Pilgrim, a man who becomes unstuck in time after he is abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore. In a plot-scrambling display of virtuosity, we follow Pilgrim simultaneously through all phases of his life, concentrating on his (and Vonnegut's) shattering experience as an American prisoner of war who witnesses the firebombing of Dresden.

Don't let the ease of reading fool you--Vonnegut's isn't a conventional, or simple, novel. He writes, "There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick, and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces. One of the main effects of war, after all, is that people are discouraged from being characters..." Slaughterhouse-Five (taken from the name of the building where the POWs were held) is not only Vonnegut's most powerful book, it is as important as any written since 1945. Like Catch- 22, it fashions the author's experiences in the Second World War into an eloquent and deeply funny plea against butchery in the service of authority. Slaughterhouse-Five boasts the same imagination, humanity, and gleeful appreciation of the absurd found in Vonnegut's other works, but the book's basis in rock-hard, tragic fact gives it a unique poignancy--and humor.

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.'s classic novel comes to life in this haunting and darkly humorous film from acclaimed director George Roy Hill. Billy Pilgrim (Michael Sacks) is an ordinary World War II soldier with one major exception: he has mysteriously become unstuck in time. Billy goes on an uncontrollable trip back and forth from his birth in New York to life on a distant planet and back again to the horrors of the 1945 fire-bombing of Dresden. This dazzling and thought-provoking drama co-stars Ron Leibman and Valerie Perrine.

Christina Jarvis

The Vietnamization of World War II in Slaughterhouse-Five and Gravity’s Rainbow

If World War II was the straightforward movie everyone could be in,Vietnam was the sequel that was so confused that it demanded a review of the original. Perhaps the seeds of a later confusion were present in the midst of seeming clarity. —George Roeder, The Censored War

Goodbye to Berlin

Erich Mendelsohn designed some of the world's finest buildings

- and helped destroy the German capital.

By Jonathan Glancey Mon 12 May 2003

Mendelsohn's mock German Village in the Utah desert,

based on a 1920s Berlin terrace.

Deep in a desiccated, Utah desert, surrounded by mountains and fringed with scorched sage and saltbush, stand the surreal remains of German Village. Out of bounds, out of place, out of time and 90 miles from Salt Lake City, it is surely the most bizarre feature of Dugway Proving Ground, a test site created by the Allied military during the second world war to develop weapons of mass destruction for use against civilian targets in Germany and Japan.

All that survives of German Village is a single block of high-gabled, prewar Berlin working-class housing. It is accurate in every respect. And it should be: commissioned by the chemical warfare corps of the US army, it was designed by Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953), the German architect who settled in the US in 1941 after a spell in England.

I was alerted to the story of German Village by Mike Davis, who features it in his provocative book Dead Cities: A Natural History, a study of the vulnerability of modern cities from New York to Tokyo to destruction by man and nature. Mendelsohn's involvement in this deathly project, seemed, at first, bizarre. A Jew from Allenstein in East Prussia (today, Olsztyn in Poland), Mendelsohn settled in Berlin, where he trained as an architect after studying economics in Munich. From the trenches of the great war he sent home visionary sketches of extraordinary streamlined, or expressionist, buildings. In 1919, during the great flu epidemic, he began work on the Einstein Tower, an astrophysics laboratory for the German mathematician and scientist, at Potsdam on the edge of Berlin.

Over the next 10 or 12 years, Mendelsohn developed beautiful, sweeping, clean-lined, light-filled architecture - much of it in Berlin - that appeared to catch the spirit of the old German Enlightenment and represent it afresh in the uncertain days of the Weimar Republic. These included the Metal Workers Union building, the Universum Cinema on Kurfürstendamm, the Columbushaus (Galeries Lafayette) and several villas, including his own. Outside Berlin, the streamlined department stores he built for Schocken at Nuremberg, Stuttgart and Chemnitz were hugely influential worldwide.

Mendelsohn left for England when Hitler was voted into power in 1933. Here, with the Russian-born dandy Serge Chermayeff, he built, among a number of fine houses, the De la Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea.

How can this Erich Mendelsohn be the architect of the dark and deathly German Village in the Utah desert? Mendelsohn left no correspondence or notebooks relating to the Dugway Proving Ground project, where napalm and poison gases were developed and tested. He had been under gas attack in the trenches, yet it is hard not to think that his primary motivation in the desert of Utah was revenge on the Nazis. If this seems fair enough, what remains disturbing is the fact that this work was expressly designed to destroy working-class districts of Berlin, including Wedding and Pankow. These had been communist strongholds, virulently anti-Hitler, before the Gestapo and SS all but destroyed opposition to the Nazi regime.

A concerted Allied attack, by the British and US air force on working-class districts of German and Japanese cities had, however, become more or less official policy by 1943. Churchill wanted to gas them. Killed and mutilated in sufficient numbers, the German working class would, he argued, rise up against Hitler and bring a quick end to the war. "It is absurd to consider morality on this topic," he told RAF planners when the first German V1 rockets fell on London. "I want the matter studied in cold blood by sensible people, and not by psalm-singing uniformed defeatists."

Sensible people included the prime minister's favourite scientific adviser, Professor Frederick Lindemann (Lord Cherwell), who insisted that "the bombing must be directed essentially against working-class houses. Middle-class houses have too much space around them, and so are bound to waste bombs." Psalm-singing uniformed defeatists included the US's air force's celebrated commander Jimmy Doolittle, who took against Churchill's proposed Operation Thunderclap that aimed to kill 275,000 Berliners in a single 2,000-plane raid scheduled for August 1944. It did not take place.

Washington's war secretary Henry Stimson said he did not want "the United States to get the reputation of outdoing Hitler in atrocities". His less diplomatic deputy, Robert Lovett, pleading the case for adopting anti-personnel bombs loaded with napalm and white phosphorous, said: "If we are going to have a total war, we might as well make it as horrible as possible." Churchill trumped Lovett by calling on US president Franklin D Roosevelt to speed up production of a promised 500,000 top-secret "N-bombs" - filled with anthrax, developed at Dugway - to be dropped on Berlin and five other German cities.

As the debate raged in political and military circles, Mendelsohn, with scientists from Standard Oil and German-emigre set designers from Hollywood's RKO studio, set to work on German Village. RKO expertise contributed the design of proletarian Berlin interiors down to the last detail. Using forced labour (inmates from Utah state prison), German Village and its six "mietskasernen" (rent barracks) apartment blocks were completed in 44 days, in time for experiments scheduled from May 1943.

Mendelsohn and his team had done a good job. Their designs were far superior to the German housing built in England for test destruction by the RAF at Harmondsworth, near Heathrow airport. Assaulted by napalm, gas, anthrax and incendiary bombs, German Village was rebuilt several times during 1943. Nearby, the Japanese Village (long since vanished), designed by the Czech-educated architect Antonin Raymond (1888-1976), paved the way for incendiary attacks on working-class districts of Tokyo. On March 9 1945, 334 US air force B-29 superfortress bombers dropped 2,000 tons of napalm and magnesium incendiaries on the timber and paper houses of Asakusa. Officially, 83,793 Japanese were killed, 40,918 injured and 265,171 buildings destroyed. The same month, German Village aided the fire raids on Dresden. By the time Germany surrendered in May 1945, US and British raids had destroyed 45% of German housing. And, as Davis wryly observes: "Allied bombers pounded into rubble more 1920s socialist and modernist utopias than Nazi villas."Mendelsohn was the architect of some of the very best of these white, concrete dreams. Dugway, Davis argues, "led the way to the deaths of, say, two million Axis civilians", and German Village remains "a monument to the self-righteousness of punishing 'bad places' by bombing them".

There is no doubt that Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan had to be defeated; but did the Allies really need German Village, Japanese Village and the refined architectural efforts of Mendelsohn and Raymond? At the fiery dawn of the 20th century, beneath the civilised, enlightened facades of Britain and the US, as well as Germany and Japan, was a desire for expansion, destruction and terrible revenge. Sitting on the sun-deck of Mendelsohn's pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea, this axis of modern evil seems so very far removed, as far away, in fact, as the sole surviving "rent barrack" of German Village, Utah.

· Dead Cities: A Natural History by Mike Davis, The New Press, £16.95.

Deep in a desiccated, Utah desert, surrounded by mountains and fringed with scorched sage and saltbush, stand the surreal remains of German Village. Out of bounds, out of place, out of time and 90 miles from Salt Lake City, it is surely the most bizarre feature of Dugway Proving Ground, a test site created by the Allied military during the second world war to develop weapons of mass destruction for use against civilian targets in Germany and Japan.

All that survives of German Village is a single block of high-gabled, prewar Berlin working-class housing. It is accurate in every respect. And it should be: commissioned by the chemical warfare corps of the US army, it was designed by Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953), the German architect who settled in the US in 1941 after a spell in England.

I was alerted to the story of German Village by Mike Davis, who features it in his provocative book Dead Cities: A Natural History, a study of the vulnerability of modern cities from New York to Tokyo to destruction by man and nature. Mendelsohn's involvement in this deathly project, seemed, at first, bizarre. A Jew from Allenstein in East Prussia (today, Olsztyn in Poland), Mendelsohn settled in Berlin, where he trained as an architect after studying economics in Munich. From the trenches of the great war he sent home visionary sketches of extraordinary streamlined, or expressionist, buildings. In 1919, during the great flu epidemic, he began work on the Einstein Tower, an astrophysics laboratory for the German mathematician and scientist, at Potsdam on the edge of Berlin.

Over the next 10 or 12 years, Mendelsohn developed beautiful, sweeping, clean-lined, light-filled architecture - much of it in Berlin - that appeared to catch the spirit of the old German Enlightenment and represent it afresh in the uncertain days of the Weimar Republic. These included the Metal Workers Union building, the Universum Cinema on Kurfürstendamm, the Columbushaus (Galeries Lafayette) and several villas, including his own. Outside Berlin, the streamlined department stores he built for Schocken at Nuremberg, Stuttgart and Chemnitz were hugely influential worldwide.

Mendelsohn left for England when Hitler was voted into power in 1933. Here, with the Russian-born dandy Serge Chermayeff, he built, among a number of fine houses, the De la Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea.

How can this Erich Mendelsohn be the architect of the dark and deathly German Village in the Utah desert? Mendelsohn left no correspondence or notebooks relating to the Dugway Proving Ground project, where napalm and poison gases were developed and tested. He had been under gas attack in the trenches, yet it is hard not to think that his primary motivation in the desert of Utah was revenge on the Nazis. If this seems fair enough, what remains disturbing is the fact that this work was expressly designed to destroy working-class districts of Berlin, including Wedding and Pankow. These had been communist strongholds, virulently anti-Hitler, before the Gestapo and SS all but destroyed opposition to the Nazi regime.

A concerted Allied attack, by the British and US air force on working-class districts of German and Japanese cities had, however, become more or less official policy by 1943. Churchill wanted to gas them. Killed and mutilated in sufficient numbers, the German working class would, he argued, rise up against Hitler and bring a quick end to the war. "It is absurd to consider morality on this topic," he told RAF planners when the first German V1 rockets fell on London. "I want the matter studied in cold blood by sensible people, and not by psalm-singing uniformed defeatists."

Sensible people included the prime minister's favourite scientific adviser, Professor Frederick Lindemann (Lord Cherwell), who insisted that "the bombing must be directed essentially against working-class houses. Middle-class houses have too much space around them, and so are bound to waste bombs." Psalm-singing uniformed defeatists included the US's air force's celebrated commander Jimmy Doolittle, who took against Churchill's proposed Operation Thunderclap that aimed to kill 275,000 Berliners in a single 2,000-plane raid scheduled for August 1944. It did not take place.

Washington's war secretary Henry Stimson said he did not want "the United States to get the reputation of outdoing Hitler in atrocities". His less diplomatic deputy, Robert Lovett, pleading the case for adopting anti-personnel bombs loaded with napalm and white phosphorous, said: "If we are going to have a total war, we might as well make it as horrible as possible." Churchill trumped Lovett by calling on US president Franklin D Roosevelt to speed up production of a promised 500,000 top-secret "N-bombs" - filled with anthrax, developed at Dugway - to be dropped on Berlin and five other German cities.

As the debate raged in political and military circles, Mendelsohn, with scientists from Standard Oil and German-emigre set designers from Hollywood's RKO studio, set to work on German Village. RKO expertise contributed the design of proletarian Berlin interiors down to the last detail. Using forced labour (inmates from Utah state prison), German Village and its six "mietskasernen" (rent barracks) apartment blocks were completed in 44 days, in time for experiments scheduled from May 1943.

Mendelsohn and his team had done a good job. Their designs were far superior to the German housing built in England for test destruction by the RAF at Harmondsworth, near Heathrow airport. Assaulted by napalm, gas, anthrax and incendiary bombs, German Village was rebuilt several times during 1943. Nearby, the Japanese Village (long since vanished), designed by the Czech-educated architect Antonin Raymond (1888-1976), paved the way for incendiary attacks on working-class districts of Tokyo. On March 9 1945, 334 US air force B-29 superfortress bombers dropped 2,000 tons of napalm and magnesium incendiaries on the timber and paper houses of Asakusa. Officially, 83,793 Japanese were killed, 40,918 injured and 265,171 buildings destroyed. The same month, German Village aided the fire raids on Dresden. By the time Germany surrendered in May 1945, US and British raids had destroyed 45% of German housing. And, as Davis wryly observes: "Allied bombers pounded into rubble more 1920s socialist and modernist utopias than Nazi villas."Mendelsohn was the architect of some of the very best of these white, concrete dreams. Dugway, Davis argues, "led the way to the deaths of, say, two million Axis civilians", and German Village remains "a monument to the self-righteousness of punishing 'bad places' by bombing them".

There is no doubt that Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan had to be defeated; but did the Allies really need German Village, Japanese Village and the refined architectural efforts of Mendelsohn and Raymond? At the fiery dawn of the 20th century, beneath the civilised, enlightened facades of Britain and the US, as well as Germany and Japan, was a desire for expansion, destruction and terrible revenge. Sitting on the sun-deck of Mendelsohn's pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea, this axis of modern evil seems so very far removed, as far away, in fact, as the sole surviving "rent barrack" of German Village, Utah.

· Dead Cities: A Natural History by Mike Davis, The New Press, £16.95.

Web result

German Village (Dugway Proving Ground) - Wikipedia

MacArthur fellow Mike Davis is the author of “City of Quartz”, “Ecology of Fear”, “Magical

Urbanism”, and -- with Kelly Mayhew and Jim Miller -- of “Under the Perfect Sun”. He lives

in San Diego.

Errol Morris is a filmaker who produced such works at Vernon, Florida, The Thin Blue Line,

and Fast, Cheap & Out of Control.

Recently I read a chapter from Mike Davis' Dead Cities that reminded me of part of Errol

Morris' documentary Fog of War. They both talk about the use of firebombs in World War II:

bombs designed not to destroy military compounds but rather to destroy dense, urban

civilian populations in order to weaken the morale of the enemy.

firebomb n : a bomb that is designed to start fires; are most effective against flammable

targets (such as fuel) [syn: incendiary bomb, incendiary] v : attack with incendiary bombs;

"The rioters fire-bombed the stores"

Search Results

Sep 5, 2018 - 20 posts - 6 authors

The bombing of Dresden was a British/American aerial bombing attack ... By now, the thousands of fires from the burning city could be seen more ... In the Utah desert, during the Second World War, the Americans ... From Mike Davis ... Tokio not A Bombed, (burning in Napalm) looks similar to Hiroshima ?Web results

fire power not only has the ability to destroy assets physically; it is also a most useful weapon ... coalition's offensive air campaign during Operation Desert Storm ... Biddle, Tami Davis, “British and American Approaches to Strategic Bombing: Their Origins and ... Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima and Hamburg, may drive home to.

180 DEGREES OUT: The Change in U.S. Strategic Bombing Applications, 1935-1955.

By John M. Curatola

Professor Theodore A. Wilson, Advisor

This dissertation examines how the U.S. Army/Air Force developed strategic bombing

applications during the 1930s and then changed them during World War II and in early

Cold War planning. This narrative history analyzes the governmental, military, and

social influences that changed U.S. bombing methods. The study addresses how the Air

Force diverted from a professed strategy of precision bombardment during the inter-war

years only to embrace area, fire, and atomic bombardment during WW II. Furthermore,

the treatise continues in this vein by examining how the USAF developed atomic and

thermonuclear applications during the post war era and the Cold War.

Oct 2, 2014 - As Mike Davis recalls, initial discussions of singling out the mansions of the Nazi ... a replica of the slum districts of Berlin was built in the Utah desert, ... but Roosevelt eventually came around, and the bombing of Dresden was ... had had his eye on the potential for firebombing Japan as far back as 1932: ...

A look at the Allied “Revenge Bombings” in Dresden, Berlin, Tokyo, ... Accounts describing the “Battle of Britain” refer to these bombings but ... Boren, Zachary Davies. ... Heavy AA fire prevented them from being accurate; the bombs caused

bombing with Kaiser-made "goop" had ...

Desert Storm. ... Tokyo and Dresden, area bombing in both theaters of war, and the dropping of the ... indiscriminate civilian attacks as firebombing, area bombing, and the ... Michael Walzer and William V. O'Brien, believe that jus ad bellum ... Tami Davis Biddle, "Air Power," in The Laws of War: Constraints on Warfare in the.

Berlin and Tokyo resonated favorably with public opinion at the time, changing ... One can find numerous histories of specific strategic bomb- ... Richard G. Davis. Since ... B-17 Flying Fortresses attack railway centers in Dresden . ... B-29s drop fire bombs on Yokohama . ... Coalition Sorties against Scuds, DESERT STORM .

Aerial Attacks on Civilians and the Humanitarian Law of War ...

by M Lippman - 2002 - Cited by 40 - Related articles

See George B. Davis, The Launching of Projec- tiles from ... ary 1945 attack on Dresden in eastern Germany.67 Estimates are that, follow- ... the fire-bomb raids as "one of the most ruthless and barbaric killings of non- ... Judge Michael A. ... See International Military Tribunal at Tokyo (1948), in II THE LAW OF WAR: A.

by H Reinhold - 2002 - Cited by 12 - Related articles

Dec 15, 2005 - Ambassador David C. Scheffer, Lieutenant Colonel Michael A. Newton and Major ... EDOIN, THE NIGHT TOKYO BURNED (1987); Chris af Jochnick & Roger ... editorial, Simon Jenkins called firebombing, such as Dresden, ... Also called "The Second Persian Gulf War" and "Operation Desert Storm."

by PA Werth - Cited by 4 - Related articles

port of Mike Hilbruner (U.S. Forest Service, retired) is sincerely appreciated. University, C. ... Davis, K.P. 1959. Forest fire: ... Desert ecotones in which fire has historically been limited by low fuel ... in 1921 when a magnitude 7.9 earthquake hit the Tokyo,. Japan ... War II city bombings of Hamburg, Dresden, and Hiroshima.

BRITAIN 1939-1945: THE ECONOMIC COST OF STRATEGIC BOMBING

By John Fahey

Department of History

The strategic air offensive against Germany during World War II formed a major

part of Britain’s wartime military effort and it has subsequently attracted the

attention of historians. Despite the attention, historians have paid little attention

to the impact of the strategic air offensive on Britain. This thesis attempts to

redress this situation by providing an examination of the economic impact on

Britain of the offensive. The work puts the economic cost of the offensive into its

historical context by describing the strategic air offensive and its intellectual

underpinnings. Following this preliminary step, the economic costs are described

and quantified across a range of activities using accrual accounting methods. The

areas of activity examined include the expansion of the aircraft industry, the cost

of individual aircraft types, the cost of constructing airfields, the manufacture and

delivery of armaments, petrol and oil, and the recruitment, training and

maintenance of the necessary manpower. The findings are that the strategic air

offensive cost Britain £2.78 billion, equating to an average cost of £2,911.00 for

every operational sortie flown by Bomber Command or £5,914.00 for every

Germany civilian killed by aerial bombing. The conclusion reached is the

damage inflicted upon Germany by the strategic air offensive imposed a very

heavy financial burden on Britain that she could not afford and this burden was a

major contributor to Britain’s post-war impoverishment.

By John Fahey

Department of History

The strategic air offensive against Germany during World War II formed a major

part of Britain’s wartime military effort and it has subsequently attracted the

attention of historians. Despite the attention, historians have paid little attention

to the impact of the strategic air offensive on Britain. This thesis attempts to

redress this situation by providing an examination of the economic impact on

Britain of the offensive. The work puts the economic cost of the offensive into its

historical context by describing the strategic air offensive and its intellectual

underpinnings. Following this preliminary step, the economic costs are described

and quantified across a range of activities using accrual accounting methods. The

areas of activity examined include the expansion of the aircraft industry, the cost

of individual aircraft types, the cost of constructing airfields, the manufacture and

delivery of armaments, petrol and oil, and the recruitment, training and

maintenance of the necessary manpower. The findings are that the strategic air

offensive cost Britain £2.78 billion, equating to an average cost of £2,911.00 for

every operational sortie flown by Bomber Command or £5,914.00 for every

Germany civilian killed by aerial bombing. The conclusion reached is the

damage inflicted upon Germany by the strategic air offensive imposed a very

heavy financial burden on Britain that she could not afford and this burden was a

major contributor to Britain’s post-war impoverishment.

Search Results

Web results

Strategic Air Warfare and Nuclear Strategy

THE FORMULATIONOF MILITARY POLICY IN THE TRUMAN ADMINISTRATION, 1945-1950

Patrick W. Steele. B.A., M.A.

Marquette University, 2010

This work analyzes the military decision making within the Truman

administration that culminated in the purchases of aircraft and the establishment of a

virtual nuclear only strategy. When Harry S. Truman became President in April 1945, the

United States Army Air Force (USAAF) was in the formative stage of a firebombing

campaign that attempted to burn the Japanese out of the war by targeting the civilian

population. Four months later, the use of nuclear bombs ushered in the atomic age and

completely altered the military and political decision-making processes within the

administration. Despite evidence to the contrary about the efficacy of strategic bombing,

the military view of the atomic bomb as an ultimate arbiter of warfare whose use virtually

guaranteed victory on American terms was immediately embraced across all the armed

forces.

Article (PDF Available) in City 8(2):165-196 · July 2004

DOI: 10.1080/1360481042000242148

Stephen Graham Newcastle University

Abstract

We tend to see contemporary cities through a peace-time lens and war as somehow exceptional. In this ambitious paper, long in historical range and global in geographical scope, Steve Graham unmasks and displays the very many ways in which warfare is intimately woven into the fabric of cities and practices of city planners. He draws out the aggression which we should see as the counterpart of the defensive fortifications of historic towns, continues with the re-structuring--often itself violent--of Paris and of many other cities to enable the oppressive state forces to patrol and subordinate the feared masses. Other examples take us through the fear of aerial bombardment as an influence on Le Corbusier and modernist urban design to the meticulous planners who devised and monitored the slaughter in Dresden, Tokyo and other targets in World War 2. Later episodes, some drawing on previously classified material, show how military thinking conditioned urbanisation in the Cold War and does so in the multiple 'wars' now under way--against 'terrorism' and the enemy within . City has carried some exceptional work on war and 'urbicide' but this paper argues that, for the most part, the social sciences are in denial and ends with a call for action to confront, reveal and challenge the militarisation of urban space.

|

| https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-1-349-16180-5 |

Introduction

My research is concerned with the ‘staging’ of the landscapes of twentieth century

military conflict in the American and European theatres of war. An investigation of the

history, theory, and application of camouflage provides the basis for a discussion of the

interrelation between camouflage and scenography. The emphasis will be on the

visualisation of landscape and the strategies adopted to control the conditions of

perception; to demonstrate how the wartime landscape was a constructed space of the

imagination- an object of vision and a place of action reinvented and redefined through

the ‘logistics of perception’ and the aerial view. The focus will be on the scenarios,

terrain models and scenic effects of the wartime scenographers. Examples of decoy

landscapes including camouflage and terrain models will be used to illustrate how

scenographic methods were deployed to create and visualise strategies of disguise and

exposure.

This is a multi-disciplinary perspective informed by a wide range of literature

concerning perception, the aerial view, the miniaturisation of landscape, the theatrical

metaphor, landscape as theatre and the theatre of war. I intend to discuss the wartime

construction of performative spaces and experiences by professional scenographers and

to analyse the construction and viewing in complex (scenographic, aesthetic,

psychological, historic) terms. Both identification and distancing were necessary for the

wartime scenographers to deal with their activities. Creativity, subjectivity and

theatricality were prerequisites to design and construct an effective terrain model and I

wish to show how the creation of a ‘theatre of war’ came to be at conflict with itself in

the work of the camoufleurs. In this dissertation I use the term strategic scenography to

refer to practices produced during wartime. The waging of war depends upon the

mobilization of a range of artistic and performative activities. The theory and practice of

conflict is not only informed by the tactical rules of engagement or the technicalities of

ballistics and surveillance, weapons systems, operations but by the language and cultural

frames provided by theatre. Similarly the strategy of the military is to impose their own

vision of war on theatre practice through recruiting manuals, training manuals,

propaganda and film

The city as destructive system: wildfires, Dresden and the case against urban sprawl

Since I wrote about the first glimpse of the bushfire season here in Sydney a few weeks ago, attention has switched to the south-west of the USA, where devastating wildfires continue to burn across California. While bushfires or wildfires have been a part of both areas since time immemorial (see also France, Portugal, South Africa, Greece, the Balkans, etc.) there seems little doubt that the drought attributed to climate change is exacerbating the situation. So fires both get worse and more widespread.

By chance I also happened to recently read an astonishing, sobering article on the bombings of Dresden and Hiroshima in the Second World War, entitled 'The Mongol devastations', by Jörg Friedrich. (Originally publishd in Die Welt, on 10 February, 2005, it's hugely enlightening on this horrific, unnecessarily brutal end to the war, amidst the post-war carve-up of Europe and Asia, suggesting that the bombing by the British and Americans was essentially just a strategic show of strength to the Russians - "the demonstration of a capacity" - using already-defeated Germany and Japan as no more than a token.)

Friedrich's article, when taken with images of the wildfires in California, and those around Australian cities in recent years, gave me pause to consider how urban form and fire are related. I don't want to use the terrible fires around California, and in Australia before them, as my own spurious token in an academic argument about urban planning. And yet I can't help but correlate urban sprawl with placing more and more people into areas consistently threatened by fire. In this, the contemporary form of the sprawling city is not only something that is bad for the city in general - you could argue that point of course, but I don't think it can really be doubted - but also just supremely dangerous.

We're now seeing deaths, upheaval of communities, destruction of property and vast economic losses. And this is to do with the form of the city,

In Friedrich's words, in their numbing horror, we see that urban form itself, as well as the motivation of bombers, either encouraged or discouraged the flames of late-World War 2. He describes the malevolent science of firebombing developed by the allies as they studied the effects of fire on various cities. These designers - why not use that word? - attempted to create more efficient city-destroying systems. In effect, they were a form of urban planner, yet looking at the landscape, structure and fabric of the city in order to destroy rather than create. Friedrich makes clear it was planning, rational enquiry and product development, with strategists asking questions such as "How could similar death zones be made to be safer, more manageable, more cost-effective and larger?" and describing the race to the atom bomb as "the most formidable development project of all time". (Disconcertingly, you can almost perceive this stance on the RAF Bomber Command's website, in the grimly satisfied terms deployed to describe their bombing of Dresden, which they still claim to have been of military importance, running against Friedrich's well-researched counterpoint.)

A lengthy quotation from Friedrich's article:

"The fire bombing of Hamburg killed 45,000 people overnight, more than the Luftwaffe had achieved in nine months of dropping bombs on England. Only eight weeks earlier,the fire in Wuppertal had resulted in 3,000 deaths, an unprecedented figure until then."

"The fire in Wuppertal burnt in the air circulation pattern particular to enclosed river valleys. In Hamburg it was the dry summer heat; in Heilbronn, Dresden and Pforzheim it was winter snow. Tokyo was built almost entirely of wood and paper, Darmstadt of sandstone, Munster of brick. Hildesheim and Halberstadt were criss-crossed by narrow streets lined with half-timbered houses, Mannheim was divided into classic quadrants, Dortmund and Duisburg were made up of sprawling 19th century blocks. The thermonuclear planners delved into the fund of knowledge left by the area bombing of the Axis powers. This was the only way to understand how individual cities burn."

"The historic fires in San Francisco, Hamburg and London had nothing in common with the procedure whereby in only 17 minutes (Würzburg) or 21 minutes (Dresden), cities were showered with hundreds of thousands of incendiary bombs. These sparked thousands of fires, which within three hours became a flaming sea, several square kilometres wide. Large natural fires normally have a single source, and are driven for days by the wind. But war statistics showed that such winds played a minor role in fires caused by bombs. The real destructive power was not in the wind that drives the fire, but in the fire itself, which unleashes its own hurricane on the ground."

"Neither buildings nor people can escape the logic of the elements of fire and air. A fire starts, it sets the air in motion, fire and air form a vortex extinguishing life and all that belongs to it: books, altars, hospitals, asylums, jails and jailers, the block warden and his child, the armourers, the people's court and all the people in it, the slave's barracks and the Jew's hideout, the strangler as well as the strangled. Hiroshima and Dresden, Tokyo and Kassel were transformed from cities into destructive systems. The agent of change is the bomb war, and the bomb war is its construction site."

Of course, the 'motives' behind the wildfires and bushfires - save for cases of arson - are entirely different, being the result of systemic interactions between wind, climate and terrain. Yet this is a dynamic system and at least one of those variables has been actively altered by humankind, and by city dwellers most of all. Developing Friedrichs' notion - that cities can become destructive systems - can we see that the form of the contemporary sprawl city, 65 years later, might be becoming a new kind of destructive system?

If the early-20th century urban forms of Hamburg, Tokyo, and Dresden set up their own destruction under the extreme conditions of their time - a bomb war, in that case - the new urban form of Sydney and San Diego in the early-21st century might also be setting up destructive systems, inadvertently unleashing a similar firestorm but at the edges of the sprawling city. In both cases, the combination of urban form introduced to a new agent of change results in the hurricane of fire: in the Second World War, firebombing destroys cities, flames sweeping from the centre out. In the 21st century, the rising temperatures create tinder-dry conditions in the bush and fire attacks the city from the edges inwards, edges that have begun to extend well into dangerous territory.

In The Economist's recent piece on the wildfires, Joel Kotkin all but suggests that cities are over-extending their reach:

"Recent (fires) have caused more damage than those 30 years ago, because the population has grown and many more Californians have moved out of city centres and built big homes surrounded by foliage. “In more remote areas, you're more susceptible to fire,” argues Mr Kotkin, “and nature still has a lot of power.”

Similarly, an excellent recent documentary on bushfires on Australia's ABC Radio National makes a similar point about the "urban interface" and its new proximity to bushfires:

"The cities are sprawling outwards, into bushland, and closer to national parks. In Melbourne, it's the hills around the city; in Sydney it's the northern and southern suburbs and the Blue Mountains area. The edges of Adelaide, Brisbane, Perth and Hobart are all places where the city now meets the bush head-on."

In the same programme, Naomi Brown, CEO of the Australasian Fire Authorities Council, sounds frustrated that people don't see this "bigger picture" of urban development's role in recent bushfires around Australian cities:

"They very rarely have the ability or the inclination to take a few steps back and look at the really big picture on what actually led up to these fires, what's happening with land management ... You know, why is the vegetation doing what it's doing, what is happening with land planning. You know why are structures and developments where they are. You very rarely get that big look at what the total picture is"

Ross Bradstock, Head of the University of Woolongong's Centre for Environmental Risk Management:

"You know, there's hard decisions to make because real estate is valuable, and people value their lifestyles and all those sorts of things. And to some degree you know, you can't have your cake and eat it. People can't live right in the bush, and expect to enjoy low risk of damage to their property. So there's always going to be hard choices to make about the way development is managed in the future"

I recall Barista's post of last year, describing how those fires affected Melbourne:

"Now Melbourne - ultra-sophisticated, urban, discursive, computerised, air-conditioned, internationalised - carries an elemental haze of smoke. I walk the dog on beaches that smell of hydrogen sulphide and ash. My partner Susie reaches fretfully for her athsma inhaler"

The site for ABC's Background Briefing has a series of images of new habitation in and around the Ku-rin-gai National Park north of Sydney, such as this street, sitting just below the fire-blackened trees on the skyline.

I'm currently reading David Peace's shattering new novel Tokyo Year Zero, which is set in the almost mortally-wounded Tokyo of 1946. The sense of the city in ruins, physically and psychologically, has rarely been rendered more evocatively - Tokyo is utterly defeated, on its knees - yet each image also implicitly prompts you to consider how Tokyo responded, building one of the most advanced, civilised and affluent cities of our time.

It is possible to calibrate the symbiotic relationship between cities and cultures - indeed, it's manipulating cities through the legislation of property development that has led to sprawl. What's more complex here, as with much these days, is that the imagery and problem is not rendered in sharp black-and-white contrast - a burnt-out Dresden or Tokyo - but is more amorphous, dynamically distributed and insidious. The sense of a few cities glowing at their edges, with a complex set of underlying causes, does not in itself provide enough traction for change. (Note Bryan Finoki's recent reportage from Flint, Michigan, a city largely in an advanced stage of decay, caught in the wake of contemporary economic development and struggling to respond. This slow demise may prove fatal, as opposed to the quick double-tap incapacitation of firebombing. Ironically, if the causal factors are apparently difficult to perceive until it's almost too late, the resolution of imagery has increased such that we can see the effects of these changes almost as vividly as those images of Dresden and Tokyo, and certainly from more angles; see the maps of CNN or Wikipedia. A form of City Informational Modeling - a derivation of BIM - may enable us to see - the changing city in real-time.)

So without undergoing world war, without the bomb as an "agent of change", we seem to have still developed the conditions for burning cities, through little more than avarice and a culture of individualism. It's not a time for pointing the finger at individuals suffering terrible upheaval and dealing with huge personal loss. It is a time, however, to look at the patterns of urban development - and the wider political context - that created this situation, with the fringes of metro areas the fastest growing parts of the USA and Australia. Not just enabling cities to sprawl but subsidising and encouraging them to do so, as Dolores Hayden suggests. In the context of accelerating a climate change, it has only increased the likelihood of bushfires in inhabited areas. This careless combination has already proved deadly in Australia and California.

The only good that could come from these ongoing reports at the singed urban interface would be an increased impetus to reverse both these trends and focus on re-building the high-density city, diminishing the need for a sprawl of over-large detached houses with their associated environmental cost, and thus remaining easily defensible against these natural fires.

The cities described by Friedrich were old European or Asian forms and, frankly, didn't stand a chance:

"... There were cities like Berlin that did not work right. The width of the streets, the firewalls, the abundance of greenery and canals opposed the fire-injections and responded wrong. But Dresden's narrow streets, decorative old town and wooden buildings fed the fires according to plan. The carefully selected triangle between the Ostragehege park and the main railway station functioned as a "fire-raiser". The old cities, bent with age, testimonies to the distant past, were best suited to such attacks. Freiburg, Heilbronn, Trier, Mainz, Nuremberg, Paderborn, Hildesheim, Halberstadt, Würzburg: this avenue of German history shared the lot of Dresden in these months. For the allied fire bomb strategists, the study of their material composition was a science in itself."

But San Diego and Sydney are new cities - New World cities, even - and if urban progress is to mean anything, they shouldn't really be on fire. The "study of their material composition" doesn't need to be that forensic for us to realise it's not scalable to sprawl. Taking a reductionist approach, as if we were allied scientists attempting to come up with a formula for destroying new cities, you might conclude:

urban sprawl + climate change = destructive fires

Aleksei Likhachev, the chief of Russian state nuclear power company Rosatom

Aleksei Likhachev, the chief of Russian state nuclear power company Rosatom