In a previous article (Quester, 2019) I introduced readers to some aspects of the life of Gustavo Rol (1903-1994), to whom many attributed disconcerting paranormal feats. I propose here to try and bring into clearer focus the man’s character and personality; his efforts to contextualize his powers - which he referred to as ‘possibilities’ - within a spiritual and ethical framework; and to debate the credibility of the extraordinary occurrences ascribed to him over more than six decades of his adult life.

By way of introduction, I begin with a few representative anecdotes reported by Remo Lugli (1997), a highly respected Italian journalist and writer. His book is generally regarded as one of the most accurate biographical accounts of Rol’s life, whom he regularly frequented from 1972 to 1980. Lugli includes numerous testimonies from his own experiences, and from several other sources (the complete collection of anecdotes can be found in Rol, 2018).

Source

An Experiment with Books and Cards

Lugli tells us of a letter to the Turin newspaper La Stampa, published in the 20 August 1978 edition and signed by Diego de Castro, director of the Institute of Statistics of the University of Turin, and an investigator of paranormal claims. De Castro begins by concurring with professional debunkers that most ostensibly paranormal phenomena are fraudulently produced: most, though not all. And he recounts that nearly two decades earlier Rol had been invited to lunch at the house of de Castro’s father in law, that the academic also attended. At one point, Rol invited him to pick at random a book from among a set of twenty volumes with identical hardback covers. He then asked him to choose also at random three cards from a deck belonging to the house owner and select based on the outcome a book page number. He was next instructed to hold the still closed book in his hands and press it on his chest. The book, which Rol never touched, was authored by Victor Hugo. Rol then wrote in French ‘The Valentinians slept with their bears’. De Castro opened the volume and looked up the first lines of the page, which read ‘The Valentinians sleeping with their bears’. The same procedure was followed with accurate results with one Italian and one German book. De Castro challenges anyone to find the deception in this demonstration.

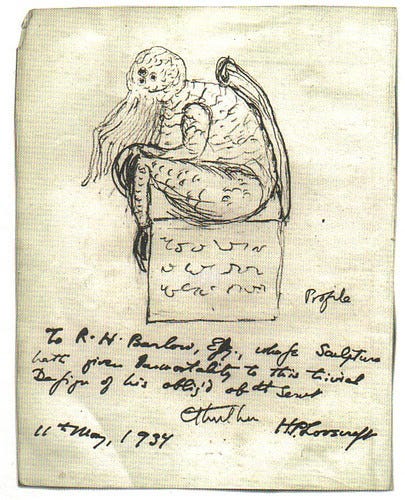

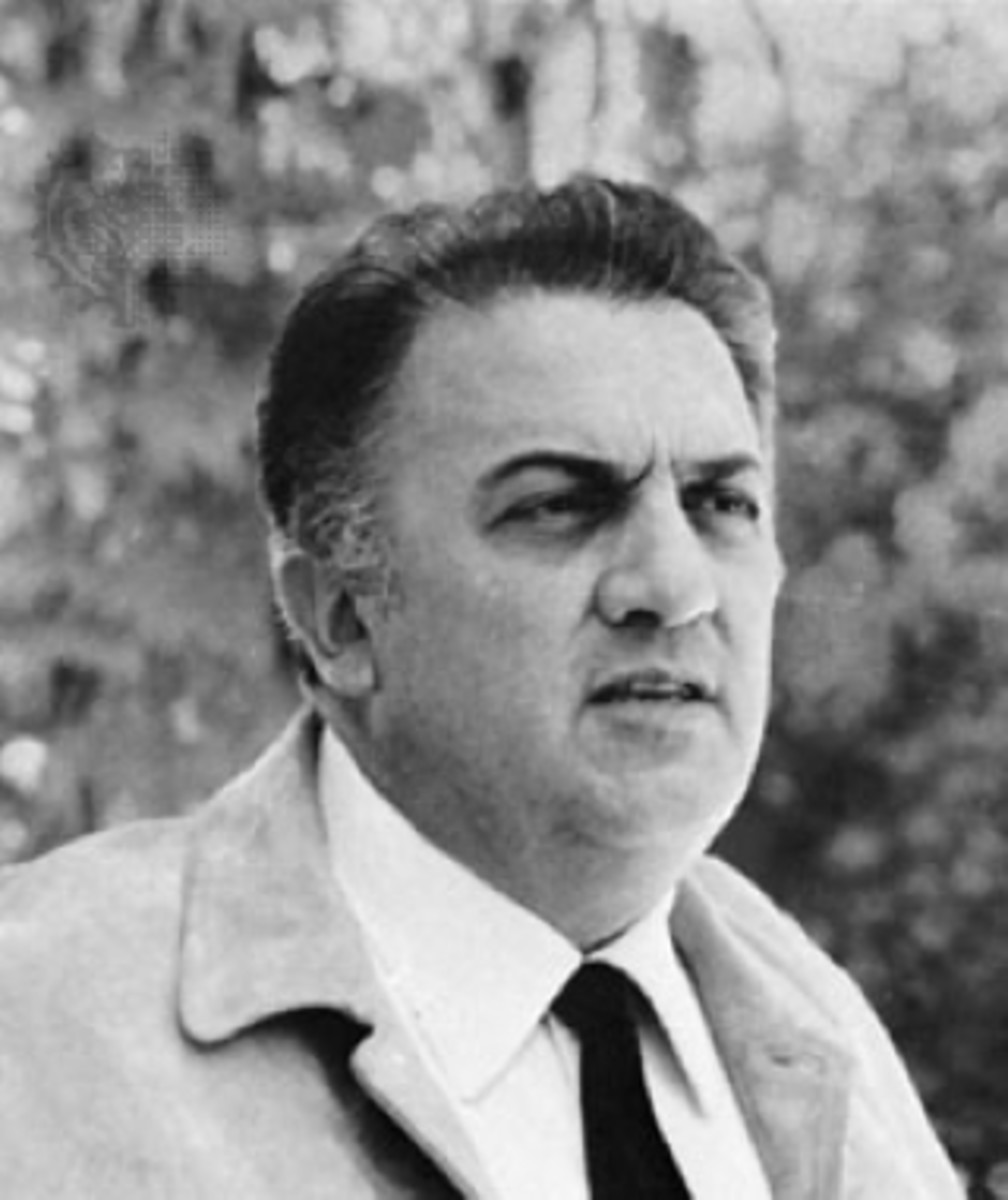

Federico Fellini in the Seventies | Source

Of a 6 of Clubs, a Hornet, and a Famous Movie Director

On the 6 August 1965 edition of the Milan based national newspaper Corriere della Sera, noted journalist and writer Dino Buzzati recounts a few episodes involving Rol and Federico Fellini - the director of acclaimed movies such as La Dolce Vita, 8 1/2, Amarcord and several others, whose centenary birth is currently being celebrated around the world -. Fellini and Rol enjoyed a close friendship that lasted from 1963 until the death of the the artist, in 1993.

The Oscar winning director told Buzzati of another ‘experiment’ also involving cards, which turned out to be somewhat disturbing.

Rol had invited him to pick up at random without showing it a playing card from a deck, which happened to be the 6 of clubs, and then to indicate which card he would like it to be turned it into; Fellini chose the 10 of hearts. Rol then instructed the artist to hold the selected card against his chest, and to make sure never to look at it. Fellini suspected that the injunction was perhaps a sly invitation to do the opposite... in any case, he was much too curious, and stole a look at the card by slightly lifting it from his chest. ‘And then I saw – in Buzzati’s reporting of Fellini’s testimony - an horrendous thing that words cannot describe.... matter was breaking up, a grey and watery mush that was quiveringly decomposing, a disgusting amalgam in which the black club symbols were melting and red streaks emerging... At this point I felt a hand grabbing my stomach and turning it upside down. An indescribable nausea... and then I found in my hand the ten of hearts.’(p. 143). Fellini felt sick and could neither sleep nor eat for two days.

Fellini again, still as reported by Buzzati. The artist and Rol were seated on a bench in the lovely Valentino Park, not far from Rol’s home in Turin. The latter was silent, a bit melancholic, immersed in his thoughts. A baby sitter was seated on another bench at some distance, seemingly about to doze off; her charge, an infant, was sleeping in a pram. Fellini noticed that an unusually big hornet was making rounds just above the baby carriage. ‘Look over there - he cried - we better rush and chase it away’. ‘No, no need of that’, was Rol’s reply. He pointed his right hand in the direction of the insect, snapped his fingers, and the hornet immediately fell onto the ground, stone dead. ‘Oh, I am sorry - Rol continued – I should not have let you see this!’(p. 143 ).

Parco del Valentino, Turin Italy | Source

Annamaria Is Very Sick

Rol frequently visited hospitals trying to be helpful to patients, and on several occasions addressed strangers on the streets advising them of seeing their doctors urgently, having perceived a danger to their health that apparently was always confirmed. He was also repeatedly asked by physicians and surgeons to help them with a diagnosis and even to attend especially challenging surgeries, and according to these practitioners he was invariably helpful.

The following episode is fairly typical of several others. On a day in August 1972 in Turin Rol happened to meet an acquaintance, the owner of a car repair shop. He found him in a state of dejection and asked the reasons for it. It was about his daughter Annamaria, recovered in a hospital for a severe case of meningitis. She was in a coma, and according to the medical team her case was hopeless, probably terminal. Even if she recovered from the coma, he was told, she would be seriously handicapped for the rest of her life. Rol requested a photograph of Annamaria, and when he had it in his hands declared with assurance ‘We shall save her, do not worry, we shall save her’. (p. 140). He left with the photograph. A few days later the girl recovered from her coma, steadily improved, and was eventually declared in complete remission, with no adverse consequences. The curing physicians regarded this as a sort of medical miracle. Annamaria went on to enjoy a full and healthy life, married and had two children.

St. Joseph of Cupertino is lifted in flight at the

site of the Basilica of Loreto, by Ludovico Mazzanti

(18th century) | Source

Why Did Rol Refuse Any Test of His ‘Possibilities’?

On the front page (!) of La Stampa on 13 August 1978, Arturo Carlo Jemolo, a highly regarded jurist and academic, addressed a ‘respectful’ appeal to Gustavo Rol - whose seriousness, disinterestedness and moral integrity he fully acknowledged ‘along with everybody’ - that he accept to submit to a rigorous scrutiny of his extraordinary ‘experiments’, by allowing for instance the introduction of audiovisual apparatus in his home when producing his marvels, and more generally by submitting to laboratory based tests of his abilities. The article generated a number of letters in the following days from members of the academic and scientific community, including the one by de Castro referred to above.

Jemolo’s invitation was by no means the only one that Rol received over the years from researchers in Italy and abroad. He invariably declined to submit to such ‘scientific’ tests. Also, although some of the ‘experiments’ that he carried out either in his own or in friend’s homes were attended by magicians - supposedly especially adept at detecting trickery -, he admitted these individuals purely on a basis of friendship, and always refused to invite other professional stage magicians who had repeatedly made such a request.

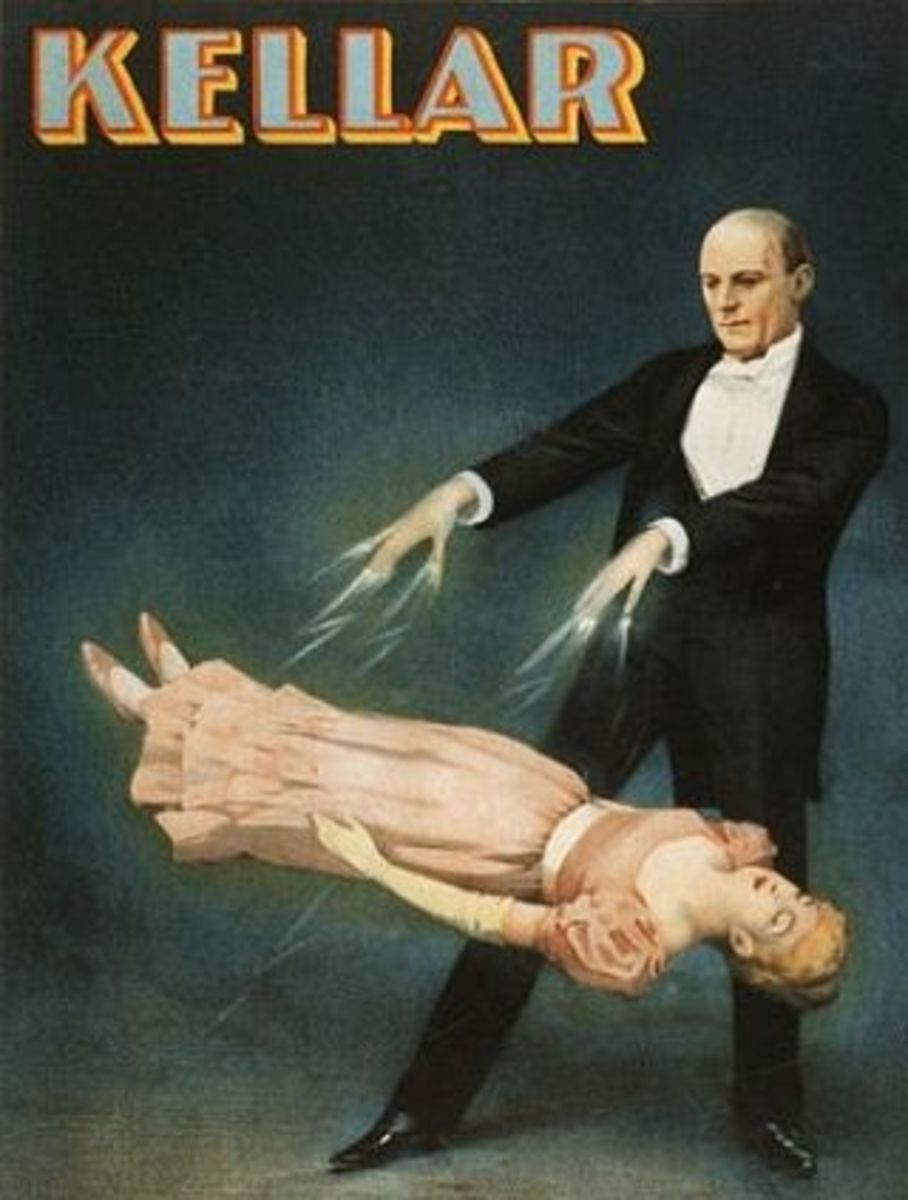

A few magicians who never attended Rol’s experiments claimed that a large part of them - especially those involving the manipulation of playing cards and others seemingly requiring telepathic and clairvoyant powers - could be duplicated with the use of ordinary techniques employed by stage conjurers and illusionists.

Whereas this may well be the case in a general way, it is essential to appreciate that reproducing a certain effect under conditions different from those applying to the original experiment is hardly probatory for dismissing the latter’s authenticity. A stage magician can simulate to great effect a person’s ability to levitate through the use of appropriate contrivances. This hardly denies by itself the reality of levitation if indeed obtained under non contrived circumstances, as claimed for instance for a number of Christian mystics and saints (most notably perhaps Saint Joseph of Cupertino (1603-1663), the subject of a recent study by Michael Grosso, 2015). Also, as noted, a few magicians did attend Rol’s experiments, and testified to the soundness of his procedures.

Rol outlined a number of reasons for refusing any systematic testing of his abilities under well controlled conditions.

Perhaps most importantly, he always insisted that he was not in a position to produce or reproduce his phenomena at will, simply because he had no control over them. They occurred spontaneously, though not randomly, ‘almost like the impulse of an unknown order’, he wrote quoting Goethe, or often when driven by a desire to be helpful. The exercise of his ‘possibilities’ occurred in an altered state of consciousness whose access - it is not hard to imagine - was not favored by the kind of physical, psychological and social conditions a laboratory environment usually provides.

Many people, including some scientists, all too often tend to discount the fact that a method of investigation should be tailored to its object, not the other way around; and when they do, the results are unlikely to be satisfactory. For instance, Behaviorism, the dominant system of psychology in North America for a good half of the past century, in its drive to develop a scientific psychology modeled upon the physical sciences enforced research protocols from which not just the ‘soul’, but even the ‘mind’ was expunged, all that remained being the study of functional relationships between an extremely simplified ‘environment’ and basic behavioural responses, best exemplified by studies of animal behaviour. Although this approach did produce many valuable findings, it ultimately proved unable to do justice to the complexities of human nature.

In short, it is reasonable to require that a research methodology be appropriate for its subject matter. Rol himself in early September 1978 replied to the public invitations from Jemolo and others discussed above (Lugli, 1995, p.190 ff.). He noted that at one time he had believed that his ‘possibilities’ were biologically based, and as such, he seemed to imply, amenable to standard scientific investigation. Yet, after attempting no better specified ‘controls’ to identify the bio-psychological basis of his possibilities, he found that his powers vanished, and returned only after he dismissed this approach. He then realized that their occurrence had an altogether different origin. According to Rol abilities such as his belong strictly to the realm of spirit, which science at present is incapable of capturing within its physicalistic nets.

However, as stated by Franco Rol (2014), ‘[Gustavo] Rol was not contrary to scientific experiments on his ‘possibilities’, and he actually spent his entire life trying to find someone in the scientific field who was suitable to receive his knowledge through a long apprenticeship as it usually occurs in the spiritual fields (in these cases, one refers to ‘initiation’). No experimentation that did not respect these criteria could be contemplated.'

Unsurprisingly, Rol’s invitation went unheeded.

Along with a refusal to subject himself to procedures of control on ‘methodological’ grounds, other variables played a role in his choice. The very idea of control carries a thinly disguised inquisitorial whiff, perhaps even including the suspicion of fraudulent behavior. This in itself could be regarded as an offensive, unnecessary and undesirable a state of affairs to submit to by someone like Rol, who never sought to gain material advantages nor explicit celebrity status from his experiments. He also always indicated that his ‘possibilities’ were effectual and deployable only within a strict ethical injunction of their being of clear benefit to others.

He insisted that undue emphasis upon his experiments detracted the attention from what these experiments pointed to and what their real significance was, which most mattered to him.

Kellar's "Levitation of Princess Karnac" | Source

A Skeptical Viewpoint

Of course, these explanations can be interpreted in a radically different way. Quite simply: Rol possessed none of the skills attributed to him; he was only a supremely gifted magician and illusionist, as indeed intimated by some members of the Italian Committee for the Control of Affirmations about the Pseudosciences (CICAP). Rol refused to submit himself to stringent controls because they would have revealed the all too earthly nature of his supposed powers.

As shown by the anecdotes described above and in my previous article, many of Rol’s feats involved real world, naturally occurring situations. Regarding the reality of these, all we have is the testimony of those who witnessed them. How believable are they? Were they perhaps in their majority dishonest, or the naive victims of trickery, or all too willingly self-deluded?

Giuditta Dembech, a friend and collaborator who has extensively written about Rol (e.g., Dembech, 2005), noted that ‘Entering his apartment was crossing a threshold into a marvelous place. One felt like Alice in Wonderland.’ (History Channel, 2014). And Remo Lugli wrote that Rol’s home ‘appeared to many as a place to dream about yet unreachable, a fairy tale address. Among his admirers, if one could boast of having been received by Rol at his home, he was looked upon as a rarity, as a person blessed by destiny, and was immediately overwhelmed by questions’ (1997, p. 29).

Is this the key to so many wondrous tales from so many people? To be able to tell the world, not only of having met the great man, but also of having assisted to one of his prodigies, the reality of which one would testify to even when personally uncertain of its reality, or even by being a willing participant in a collective deception, in order to gain a measure of glamour from it? Being admitted to Rol’s circle of intimates was notoriously difficult. What chances would one have of being retained within this circle if one were to express doubts and uncertainties about what had been seen?

A skeptic would likely find this line of reasoning entirely serviceable as a way of dismissing the reality of the many ‘impossible things’ attributed to Rol, which deeply challenge the established intellectual order, and offend the narrow rationality upon which a materialist’s world view is based (see also Quester, 2019b, 2019c). The skeptic’s explanation is most likely the correct one, she might argue, since it is by far the simplest, and based upon, not just scientistic prejudices, but the evidence of our lives, in which the marvellous rarely if at all makes its appearance for most of us. This sort of reasoning is often seen as a loose interpretation of Ockham’s razor. This would be ironic in this context, considering that the franciscan friar used it to defend the reality of miracles...

But then again, how really plausible, rational, and ‘simple’ is such a view? Rol produced his phenomena for over 60 years, in the presence of a conspicuous number of people: decent and honourable so-called ‘ordinary’ citizens, as well as denizens of the high society, many highly educated professionals including physicians and surgeons who did not hesitate to draw from his mysterious gifts in the more difficult cases, and a large number of internationally acclaimed personalities, who presumably did not need to accrue extra glamour from the frequentation of Mr. Rol. Were they all self-deluded, or worse still tacit accomplices in a deception that went on for so long?

Mariano Tomatis, a skeptic, recognizes that mere tricks could not have sufficed in creating a prestige as broad as the one Rol enjoyed. What is needed, it seems, is to realize that Rol had extraordinary charisma. His very presence - people often commented upon his commanding physique, his penetrating eyes, his authoritative manners, especially his awesome reputation, and the aura of mystery that surrounded him - enabled him ‘to act on the perception of those who saw him in action, managing even to shape the inner world of his spectators’ (Tomatis, 2009). In other words, Rol could induce people to perceive - and to further convince themselves that they were actually seeing - what was not there, or rather what he wanted them to believe was there: nothing else was needed.

In terms of this view, it was Rol’s personal charisma that led to his being granted ostensibly supernatural powers, which belief in turn induced people to perceive and attest to the impossible in accordance with his commands. But where did his remarkable charisma come from, really? What brought it about?

Max Weber (1864-1920), the immensely influential sociologist, wrote extensively upon the origins of authority in society, including what he referred to as 'pure charisma' (see Hansen, 2001). And he emphasized that the granting of such charismatic authority demands that the recipient first prove him- or herself by performing miracles, by displaying superior paranormal powers. In Weber’s view then the display of such powers is the precondition for a person’s charisma, whereas in Tomati’s thinking as I understand it the attribution of paranormal powers, which led people to perceive and believe in accordance with the charismatic’s Rol’s wishes, resulted from his otherwise acquired authority. Were Rol’s remarkable personal attributes enough? Unlikely. What then? Plain trickery? If so we are back to the beginning, for Tomatis doubts this to be a sufficient factor.

The question of whether Rol was but an illusionist in turn begs the question of his motivations, and of his character. Was he the kind of person who could be tempted by a long life of deceit? What could he gain from it, given that beyond a selected group of friends and acquaintances he always refused to give public demonstrations of his abilities, refused to appear in TV shows, declined to be turned into a celebrity or a sort of guru surrounded by throngs of adoring disciples, never accepted any money from those he helped, and indeed frequently and generously helped people in material, physical and psychological distress? With very few exceptions, he was the recipient of a very large number of attestations of, not just his extraordinary abilities, but also of his benevolent personality and ethical scruples.

I reported in a previous article (Quester 1919a) some comments about his abilities; I may add just another one here: Prof. Giorgio Di Simone wrote that Rol ‘is beyond discussion one of the human beings most endowed with those capabilities which through their effects supersede the ordinary barriers of the physical, psychical and spiritual world, [thus enabling him] to draw on a multiplicity of perceptions and paranormal manifestations that raise him to his own dimension, a superhuman dimension...’ (Lugli, 1997, p. 172).

As for Rol the man, Dino Buzzati wrote in 1965: ‘Something beneficial radiates [from Rol] onto others. This is the essential characteristic... of those rare men who rose, by transcending themselves, to a high spiritual level, and as a consequence to authentic goodness’(Rol, 2014).

Nico Orengo, an Italian writer, poet, and journalist, saw in him an ‘extremely religious’ man, and thought of him as a ‘lay saint’.

Rol was a friend of the Agnelli family, the powerful founders of the then Turin based automaker FIAT, and of Vittorio Valletta, its CEO of from 1946 to 1966, who wrote of his ‘admiration’ for Rol and his ‘ultra-humanitarian work’. Cesare Romiti, another legendary CEO of FIAT spoke of him as a ‘mystery’ which ‘defies comprehension’.

I could continue with many other quotations emphasizing Rol’s probity and integrity; but the above ones should suffice in providing a sense of the nearly universal positive response an encounter with this man elicited.

Saint Peter Square, Rome | Source

Rol’s Spiritual Views

Gustavo Rol attempted throughout his life to understand his ‘possibilities’ by placing them within a spiritual context, which I shall but briefly touch upon here.

He always emphasized that he ought not be regarded as a nearly unique individual, a sort of mutant endowed with strange powers beyond the reach of most men and women. On the contrary, as he wrote in his diary: ‘Behind the visible world there is an invisible world hidden to our senses and to thought which is driven [bound to] by them. I have understood that man, by developing certain faculties, dormant in him, can penetrate this hidden world, the invisible world. Each one of us is an initiate, he has inside himself the key to knowledge. Magic is part of everybody’s life.’(as quoted by Izzo, 2016).

This invisible world is the world of spirit. According to Rol ’Each thing has its own spirit’(Lugli, 1997, p.3). What differentiates us from ostensibly inanimate objects is the fact that our spirit is ‘intelligent’: conscious, creative and capable of acting upon the material world even beyond the commonly acknowledged laws of nature. Along with spirit, ‘man’ is endowed with a soul who can aspire to immortality, which leaves the body upon death and returns to God who created it. The spirit instead remains on earth, as a sort of psychic residue, containing all the information pertaining to any individual’s history and abilities - an ancient view revived in the early 20th century in the West by Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) under the term ‘akaschic record’, that Rol may have arrived at independently on the basis of his own experiences.

In the case of a human being, his or her intelligent spirit has the potential of being energized and activated through the mediation of individuals like Rol capable of entering a state of ‘sublime consciousness’ - which he defined in various ways, including as a state of union with the absolute. It should therefore be clear that it is not the ‘dead’ who come back, as in the spiritualist tradition, and who intervene in seances through the mediation of a medium: just their intelligent spirit. Rol always expressed his extraneity to both the views of spiritualism and its practices.

On the other hand, Rol always declared himself a fervent Christian, and specifically a Catholic one; therefore the question of how his views cohere with Roman Catholic doctrine is of some interest. To my knowledge, the Church never pronounced itself on Rol’s thought. His views on the 'intelligent spirit' in particular have been regarded by some as fundamentally extraneous to Catholic doctrine (e.g., Introvigne, 2000).

It has been suggested (Rol, 2012) that this term be understood as referring not to a specific doctrine, but to an empirical fact, which ought to be accepted as such. Whereas this approach has the merit of defusing the matter somewhat, not everyone would be prepared to grant the term this status. Regardless, as philosophers and historians of science have made clear over the past decades, even within the most mature scientific disciplines ‘naked’ facts are in very short supply, for a scientific ‘fact’ acquires its status and significance within the context of a given theory: it is always, in other words, ‘theory laden’. Therefore, the question of how this notion - and Rol's overall views - related to his Catholicism seems to me to retain its interest.

In a letter to his brother, Rol wrote that ‘saying that God is in the sun, in the worm, in the ash of a cigarette, even in a playing card is to assert the truth.’(Rol, 2012, p. 425). And God of course is also in us, our higher attributes reflecting the fact that we were made in God’s image. It seems also clear that Rol regarded God not just as coextensive with nature, as in pantheism, but also transcending it. In philosophic parlance his views can therefore be regarded as a variety of panentheism. This view seems to me to accord with a number of Christian Churches, including the Orthodox Catholic Church, the closest to the Church of Rome on spiritual grounds. And of course, with Non-Western metaphysical traditions as well.

Rol assigned great importance to the spiritual underpinnings of his possibilities and their manifestations. As noted, he repeatedly asserted that these remarkable phenomena did not matter in themselves – except I would imagine in the case of the help he was at times able to bring to people in distress -, but as evidence of the higher reaches of human nature, for which ‘nothing is impossible’ once a certain level of spiritual development is attained; of the imperishability of its makeup; of the existence of God within and outside creation. He often regretted that this higher context went lost in favor of a facile fascination with his prodigies.

And Now What?

And so, dear reader, you decide: was Gustavo Adolfo Rol one of the most accomplished conjurers of all time, one of the most skilled illusionists, perhaps hypnotists who ever lived, who somehow managed to command the allegiance of not a few people over a very long life? Or was he something far more enigmatic and astonishing?

The choice as proposed here may seem too stark. However, although more nuanced interpretations are certainly possible, this dichotomy should be allowed to stand in a preliminary inquiry such as this one.

For what is worth, I remain uncomfortably aware of the ‘impossible’, in some cases even ‘outrageous’ nature of the feats attributed to him. I have abstained from reporting anecdotes even more extraordinary than the ones presented here because I could not bring myself to accept them. In absence of a direct personal experience under unsuspicious conditions, it is difficult for anyone with a questioning turn of mind to grant unqualified credence to the feats of this remarkable man. Even personal witnessing of this sort of events might yet leave many of us with a residue of doubt, as we are prone to doing under extraordinary circumstances - ‘I cannot believe my eyes!’-.

The great American psychologist and philosopher Williams James (1842-1910), who investigated matters paranormal for many years (though of a somewhat different nature), remarked at the end of his long quest that he remained as uncertain about the true nature of these phenomena as when he had started it, and even wondered whether such a state of affairs was meant to be, as if we were not allowed to peer beyond the curtain, so to speak.

He may well be turn out to be right.

Still, the more I learn about Rol’s life the stronger I feel that it may hide a truly wondrous mystery, and that it is in any case decidedly worthy of serious study.

1. All quotations from Italian sources are translated by J. P. Quester, the pen name of the author of this article.

Dembech, G. (2005). Rol - Il Grande Precursore, con CD, Torino, Ariete Multimedia.

Grosso, M. (2015). The Man Who Could Fly: St. Joseph of Copertino and the Mystery of Levitation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Hansen, G. P. (2001). The Trickster and the Paranormal. Xlibris Corp.

Izzo, P. (2016) Rol, La scienza e lo spirito. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=reD_RT3ljZU

Lugli, R. (1997). Gustavo Rol – Una Vita di Prodigi 2nd ed. Edizioni Mediterranee.

Rol, F. (2012) Il Simbolismo di Rol, 3rd Ed.

Rol, F. (2014). FAQ about Gustavo Adolfo Rol. Retrieved from

ht

Rol, F. (2012) Il Simbolismo di Rol, 3rd Ed.

Rol, F. (2018). The Unbelievable Gustavo Adolfo Rol. Lulu.com

Rol, F. (2018). The Unbelievable Gustavo Adolfo Rol. Lulu.com

© 2020 John Paul Quester

A recently retired academic, with a background in psychology and philosophy.