BY CHANTAL DA SILVA ON 2/27/20

The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) saw a 23 percent surge in calls in the days following disgraced film producer Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction.

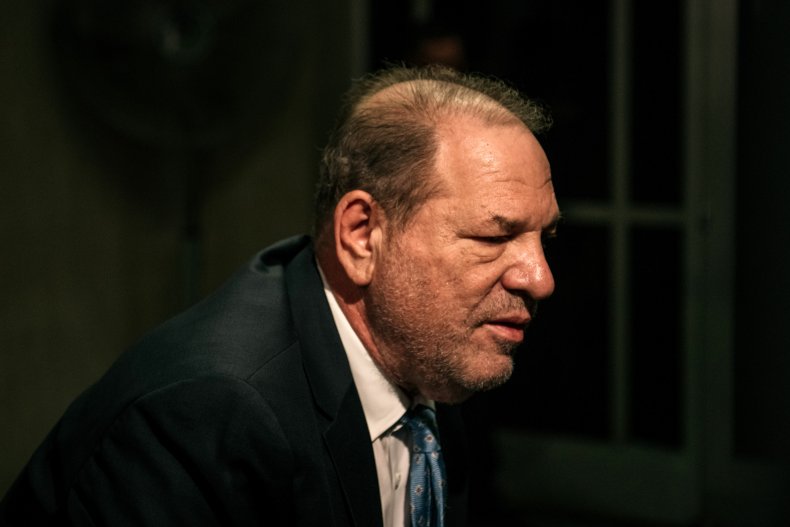

On Monday, Weinstein, 67, was found guilty on two sex abuse charges, including rape in the third degree and committing a criminal sexual act. He was acquitted of three further charges, including the two most serious charges against him of predatory sexual assault and rape in the first degree.

While the film producer has been accused of attacking dozens of women, predominantly in the film industry, the charges in this case centered around accusations made by two women: Jessica Mann and Miriam Haley, who accused Weinstein of targeting them early on in their careers.

On the day of Weinstein's conviction and on the following day, a Tuesday, RAINN said its national sexual assault hotline experienced a 23 percent increase in call volume.

In a statement shared with Newsweek, Erinn Robinson, RAINN's press secretary, said she believed "the media attention surrounding Harvey Weinstein's case is leading many more survivors to reach out for help."

In many cases, she said, women were coming to share their stories "for the first time."

Robinson said RAINN has experienced a similar effect throughout the course of other high-profile cases, including that of Bill Cosby, who had also faced widespread sexual misconduct allegations and was convicted of three counts of aggravated indecent assault in April 2018.

Disgraced movie producer Harvey Weinstein enters New York City Criminal Court on February 24, 2020 in New York City. Weinstein was convicted of sexual assault charges.SCOTT HEINS/GETTY

Disgraced movie producer Harvey Weinstein enters New York City Criminal Court on February 24, 2020 in New York City. Weinstein was convicted of sexual assault charges.SCOTT HEINS/GETTYDuring the Senate Judiciary Committee's hearing into accusations of sexual misconduct against now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, RAINN saw a massive surge in calls to its sexual assault hotline.

As Christine Blasey Ford delivered her testimony before the committee, RAINN said it had seen a 147 percent increase in calls compared with a typical weekday.

The rise in calls was so significant that RAINN had to notify users it was experiencing "unprecedented wait times" for its online chat system, while the organization encouraged those to call its hotline, 800.656.HOPE instead.

"Hearing about sexual violence in the media and online can be very difficult for survivors and their loved ones," RAINN had said in a Twitter statement. "Remember to take care of yourself during these times."

"Hopefully, the facts that a defendant with all of the power and legal resources that money can buy can be found guilty, and that public opinion was heavily in favor of the victims, will give hope to other survivors and prosecutors that these cases will be taken seriously and that they too can get justice," Robinson said in a separate statement to Newsweek.

"Having already seen an uptick in visitors to the National Sexual Assault Hotline this week, we anticipate that more survivors will reach for support. We are humbled to be able to help these survivors in their healing," she said.

This article has been updated to include a statement from RAINN's Erinn Robinson.

Correction: This article previously stated that the surge in calls to RAINN's sexual assault hotline occurred on the Tuesday and Wednesday following Weinstein's Monday, February 24 conviction. It occurred on the day of his conviction and the day following.