New documents and interviews reveal how time after time, the e-commerce giant put speed, profit, and explosive growth before public safety.

AN EXCERPT FROM

“Machine-Oriented System”

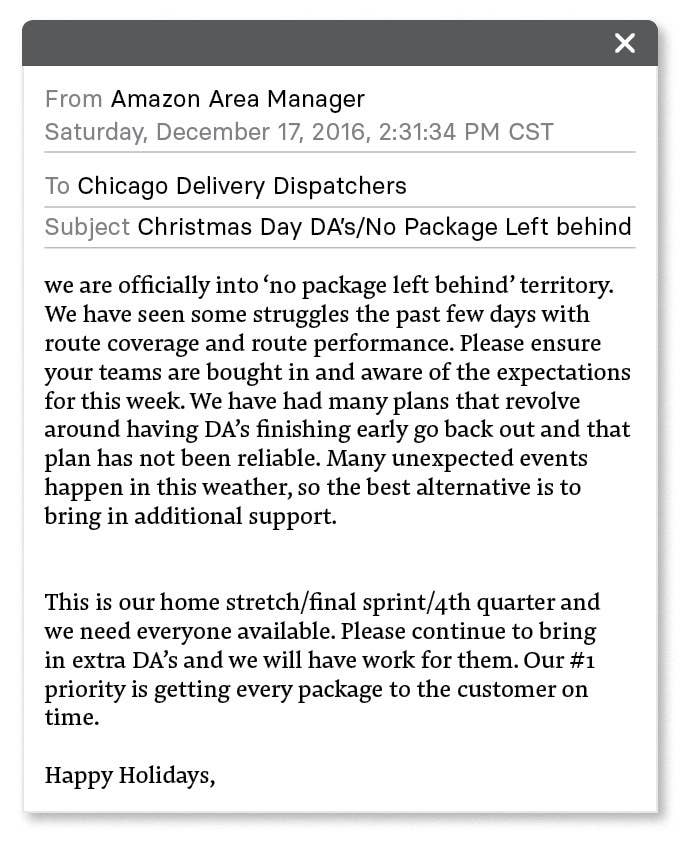

By late 2016, Amazon had launched delivery stations in most major metro areas, and it was hurrying to expand to smaller cities in order to keep up with demand. As the critical peak season approached, the pace was straining many contractors.

That fall, Amazon invited representatives from more than a dozen contractors to a New Jersey conference room overlooking Manhattan for the company’s first delivery summit. The meeting was supposed to be a forum for constructive feedback about the program. Instead, attendees recalled, it dragged on for hours as contractors barraged Amazon managers with complaints about nearly every aspect of the system they had created.

Contractors protested that Amazon forced drivers to wait for hours, then overloaded them with boxes and expected them to complete deliveries in an unrealistic time frame. Drivers quit constantly because the job, which often required them to deliver as many as 300 packages a day, was so demanding. Amazon’s unreliable routing and navigation software only made matters worse, according to two people who attended.

Amazon required delivery contractors to use an app called Rabbit, which not only scanned packages but also told drivers which packages to deliver in which order and provided turn-by-turn directions. But the company began using the in-house app before it was ready, former Amazon employees say. After the app’s launch, Trip O’Dell, a design manager, was tasked with heading a team to make improvements to Rabbit, which he described as a work in progress. “In sort of the typical Amazon way where you will try something then stomp on the accelerator, it often ends up ready, fire, aim.”

O’Dell recruited an idealistic band of designers to Amazon with the pitch that they were going to make life on the road better for drivers. But Paula Wood, a member of this group, quickly became disillusioned with the technology and Amazon’s commitment to drivers. “It was ludicrous to expect drivers to be able to deliver in the tiny slices of time,” Wood said. “They put humans into a machine-oriented system.”

Wood said that on many routes, drivers didn’t have enough time to go to the bathroom or eat, so they skipped meals and breaks and urinated in bottles. Navigation directions were terrible, she said. Drivers were, for example, directed to curbs that were no-stopping zones during rush hour. The Rabbit sent drivers on dangerous paths, back and forth across busy roads, she said, full of repeated U-turns and left turns, like the ones that killed Covey and Acerra.

Research shows left turns can be risky because they require the driver to cross oncoming traffic, and the pillar between the windshield and the door can make it harder to see pedestrians in crosswalks. The algorithm that powers the turn-by-turn directions UPS uses, by contrast, programs out most left turns.

One former Amazon manager recalled watching a driver on a ride-along pounding furiously on the phone while shouting: “I hate this Rabbit! I hate this Rabbit!”

The company said there are “hundreds of technologists at Amazon who are focused on continuously improving the functionality of the Rabbit app” and, based on feedback from drivers and contractors, it has made more than 500 changes this year alone. Amazon added that it has “included functionality to avoid left and U-turns, even if that means a route takes longer” and that drivers “have always been able to stop at any time to take a bathroom break.”

Penny Register-Shaw, a former FedEx lawyer, was hired by Amazon in September 2016 to whip the delivery contractor program into shape, according to four people familiar with the program at the time. One of her first orders of business was to attend the New Jersey summit, where at least one contractor said he felt like at last someone was listening and would present the plight of drivers to Amazon management.

But Register-Shaw had trouble persuading her bosses. She spoke gently and slowly, the cadence of her voice reflecting her Tennessee upbringing, and was interrupted so frequently by her new Amazon colleagues that she rarely finished a sentence, according to several people who worked with her.

Register-Shaw and her team proposed changes to make deliveries safer for both drivers and the public, according to interviews with people familiar with the group. They recommended a drug-testing regimen for contractor drivers who were already on the road. The plan called for random tests “so drivers would not know when they were coming,” said a person familiar with the white paper proposing the tests. But the idea was nixed by higher-ups, according to people familiar with the matter.

Asked about this account, Lunak, the Amazon spokesperson, initially said it was false. But when asked additional questions about the company’s drug-testing practices, she explained that Amazon required “comprehensive” preemployment drug screening and said that drivers “are subject to additional screening if there is reasonable cause or if there is an accident.”

At some delivery stations, drivers had to retrieve their vans from distant lots before picking up their packages, and that often put them behind schedule before they even began their routes, according to two people on Register-Shaw’s team. They said her group pushed for closer parking and when that did not happen, the group recommended that drivers’ travel time be taken into account when planning shifts. That idea did not move forward either.

Members of Register-Shaw’s team were mortified by reports of drivers urinating in bottles rather than taking bathroom breaks, and even defecating outside of customers’ homes. “Humans don’t do that unless they’re under tremendous pressure,” a former member of the team said.

In early 2018, an audit team that Register-Shaw had assigned to evaluate the growing pool of delivery contractors working for Amazon reported that it had discovered dozens of the companies were out of compliance.

Some contractors didn’t have the amount of insurance Amazon required, and others weren’t paying for legally mandated overtime and rest breaks, according to several people familiar with the audit.

The findings posed a problem for Udit Madan, the executive Amazon had just put in charge of its last-mile program, according to people familiar with the audit team’s work. Putting as many drivers on the road as possible every day was a priority for Amazon. In one delivery station, the package count nearly doubled overnight, according to a manager who worked there; the e-commerce giant could ill afford to lose established delivery partners to carry those shipments to the customer.

“You felt the pressure,” said a person close to the audit team. “If you take 200 vans off the street, that would have an impact on the customer promise of two-day delivery.”

Register-Shaw eventually took the fall, resigning rather than firing members of the audit team, according to a person familiar with the matter. The head of the audit team was forced out soon after, and the team was dispersed. When asked to comment about the details in this report, Register-Shaw, who now works for Amazon’s largest retail competitor, Walmart, answered, “I wish I could have done more.”

Amazon disputed aspects of this account, saying that its monitoring of delivery contractors has improved since the leadership reshuffle. “Due to issues with the auditing program at the time, the team was moved to a centralized compliance organization,” Amazon said in a statement. “That move and new leadership, created immediate results, including increasing the scope and rate of the audits.”

Madan did not respond to questions sent through an Amazon spokesperson. The company said it monitors its contractors’ compliance with the law and expects those who are not performing to correct their problems within 30 days or “risk having their contract terminated.”

“Our transportation network is not about anyone working faster than is safe,” Amazon said in a statement. “It’s about processes and our overall operations network coming together to be able to serve customers.”

Caroline Gutman for BuzzFeed News

Vans line up to depart after loading at the South San Francisco Amazon facility.

Stuck in the Mud

In June 2018, Amazon invited the news media to Seattle for an event at a picturesque venue overlooking Elliott Bay. Instead of unveiling a new drone or other high-tech project, Dave Clark, standing in front of a van, announced that the company was rebooting its delivery network, shifting much of its package volume to smaller contractors.

The new firms would manage between 20 and 40 routes apiece, compared with hundreds run by the bigger contractors Amazon had previously signed up. Amazon would make it as easy as possible: It helped new delivery companies with legal paperwork, arranged for leases of new vans emblazoned with the company logo and even recommended preferred vendors to handle insurance and payroll. Would-be entrepreneurs — some with no experience in logistics — rushed to sign up for the program, which handed Amazon even more control over nearly every aspect of delivery while also increasing its financial leverage over the tiny firms.

At the same time the program was gearing up, at Amazon managers were putting the final touches on an ambitious road safety plan, the one that aspired to make the company “the safest last mile carrier in the world.”

The July 2018 document, titled "World Wide Amazon Logistics on Road Safety Plan," emphasized that achieving that goal would require a radical shift in the company’s safety culture. Each delivery station, for example, would have a “number of days safe” sign on the wall, all vehicles would be professionally inspected every year for roadworthiness, prospective hires would face more vetting and Amazon would implement a zero-tolerance policy for serious safety violations.

It also detailed the plan in which instructors from the National Traffic Safety Institute would teach new drivers a “defensive driving curriculum.”

“Training is a critical first step to creating the right culture, building a shared vocabulary, and developing the right behaviors,” the plan said.

Although Amazon managers overseeing delivery initially greeted the goals of the safety plan with enthusiasm, according to one person familiar with the plan, their tune changed as the all-important peak season approached.

Between Thanksgiving and Christmas 2018, Amazon roughly doubled its shipments nationwide from the previous year, surpassing the billion package mark for the first time. The company encouraged its delivery contractors to recruit as many drivers as possible. Amazon for its part hired an additional 3,949 employee drivers in the space of just a few weeks, renting “nearly every van in the United States” for them to drive, internal documents show.

In the end, the peak 2018 season looked very little like what the safety team had laid out in its proposal just four months earlier.

Employees charged with inspecting new delivery stations for safety compliance noted in an internal memo that they had been unable to visit every new station prior to launch. In some stations they did manage to visit during peak season, they were chagrined to discover scenes of chaos: inadequately trained managers, severe understaffing, haphazard traffic flows for delivery vans entering and exiting stations, and packages scattered on the floor.

Many of the stations were little more than tents erected in suburban parking lots, referred to internally as “Carnival” stations. Often, the sites suffered from a shortage of bathrooms, unsanitary working conditions, insufficient heat, a lack of ice scrapers for vehicles and poor drainage, according to internal memos and interviews with current and former Amazon employees. Some stations flooded, drivers and packages were “exposed to wind, rain, and snow,” and some parking lots became mired in thick mud that stranded delivery vans. One memo offered a solution for the mud: Put bags of kitty litter in every van.

Human resources employees complained that they “operated with a skeleton crew” while being tasked with recruiting and hiring thousands of seasonal employees who were subsequently taught how to do their jobs by instructors who “lacked the requisite skills to train someone.”

Last January, various departments within Amazon’s logistics operation shared memos detailing “lessons learned” during 2018’s peak season.

Managers overseeing the delivery contractors lamented that there was still “no current metric to measure safety” among their tens of thousands of drivers. During peak, those managers noted, drivers were frequently caught speeding through parking lots, yet there was no way to hold them accountable.

In a memo filed this past January by the group overseeing delivery contractors, one manager warned, “We need a greater focus on safety.”

A group at Amazon responsible for education and training, meanwhile, reported in its memo that it had fallen far short of its hiring goals for driver trainers. Nearly three weeks after peak season ended, 24 delivery stations still didn’t have any driver training at all, the memo said.

In a statement, Amazon said all delivery drivers are required to undergo training “before they are able to deliver even one package.” The company also said that the use of interim facilities such as Carnival stations is “standard practice” in the logistics industry and that it is currently converting those sites into permanent delivery stations.

Internal Amazon documents show that managers in charge of the delivery contractor program worried that the pressure on the system would only intensify during the 2019 holiday rush, as Amazon planned to build 80 new delivery stations, triple the size of its delivery contractor program, and, in April, make overnight delivery the default option for Prime members.

In a memo filed this past January by the group overseeing delivery contractors, one manager warned, “We need a greater focus on safety.”

Bloomberg / Getty Images

Demonstrators hold signs outside Jeff Bezos's penthouse during a protest in New York City on Dec. 2.

Fantastic Plus

Today, Amazon’s delivery operations are under increasing scrutiny as the press, politicians and Amazon’s own former managers question the company’s aggressive approach to logistics.

Citing the BuzzFeed News and ProPublica investigations on the hidden human toll of Amazon’s delivery network, US Sen. Richard Blumenthal in September lambasted the company. On Twitter he called Amazon “callous,” “heartless,” and “morally bankrupt.”

Amazon’s Clark tweeted back, “Senator you have been misinformed.” He wrote that the company took responsibility for its actions and had requirements for safety, insurance, and “numerous other safeguards for our delivery service partners which we regularly audit for compliance.”

A few days later, Blumenthal and two other senators, Sherrod Brown and Elizabeth Warren, demanded answers from Bezos.

“Innocent bystanders — as young as 9 months old — have lost their lives and sustained serious injuries from drivers improperly trained and under immense pressure by Amazon to meet delivery deadlines,” the senators wrote in a September letter to Jeff Bezos. “It is simply unacceptable for Amazon to turn the other way as drivers are forced into potentially unsafe vehicles and given dangerous workloads.”

In the run-up to this year’s peak season, Amazon has adjusted the benchmarks it uses to monitor the performance of its delivery contractors, introducing new safety metrics, according to interviews with delivery contractors and reviews of scorecards used to measure their performance. For example, Amazon began tracking the use of seatbelts by drivers and incorporating that data into weekly scores for delivery businesses. Data is collected through an app that most drivers must use and that monitors speed, acceleration, and braking, among other metrics.

Every week, Amazon rates the performance of its more than 800 delivery contractors. Those that earn the highest scores — identified by Amazon as “fantastic” or “fantastic plus” — receive bonus pay, which some delivery contractors say can represent the difference between losing money or turning a profit.

In a scorecard from November, safety represented 17% of the total score, compared with 33% for a category labeled “quality.” Amazon said that if a delivery contractor doesn’t have a high combined score in its safety and compliance metrics, it cannot reach “fantastic” or “fantastic plus” overall, and that firms that consistently receive low scores can be threatened with termination or see their routes reduced.

In the end, Bezos didn’t reply to the senators’ letter. Instead, a company lobbyist did. He wrote that Amazon empowered hundreds of small businesses through its delivery contractor program and outlined safety and labor compliance tools that he said went far beyond what’s required by law.

“Safety,” the lobbyist wrote, “is Amazon’s top priority.”

One month after that letter was sent, a contractor delivering Amazon packages in a suburban Chicago townhouse complex turned left on a private drive, striking a toddler who had wandered into a puddle in the roadway.

“She didn’t see him,” said Deputy Chief Ron Wilke of the Lisle Police Department, which is still investigating the crash.

The 23-month-old boy died at the hospital that same day. ●

MORE ON THIS

Amazon’s Next-Day Delivery Has Brought Chaos And Carnage To America’s Streets — But The World’s Biggest Retailer Has A System To Escape The Blame Caroline O'Donovan · Aug. 31, 2019

Amazon Is Firing Its Delivery Firms Following People's Deaths Ken Bensinger · Oct. 11, 2019

Ken Bensinger is an investigative reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in Los Angeles. He is the author of "Red Card," on the FIFA scandal. His DMs are open.

Caroline O'Donovan is a senior technology reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in San Francisco.

James Bandler is a senior reporter covering business and finance at ProPublica

Patricia Callahan is a senior reporter covering business for ProPublica.

Doris Burke is a research reporter at ProPublica.

Last updated on December 24, 2019, at 4:23 p.m. ET

“Machine-Oriented System”

By late 2016, Amazon had launched delivery stations in most major metro areas, and it was hurrying to expand to smaller cities in order to keep up with demand. As the critical peak season approached, the pace was straining many contractors.

That fall, Amazon invited representatives from more than a dozen contractors to a New Jersey conference room overlooking Manhattan for the company’s first delivery summit. The meeting was supposed to be a forum for constructive feedback about the program. Instead, attendees recalled, it dragged on for hours as contractors barraged Amazon managers with complaints about nearly every aspect of the system they had created.

Contractors protested that Amazon forced drivers to wait for hours, then overloaded them with boxes and expected them to complete deliveries in an unrealistic time frame. Drivers quit constantly because the job, which often required them to deliver as many as 300 packages a day, was so demanding. Amazon’s unreliable routing and navigation software only made matters worse, according to two people who attended.

Amazon required delivery contractors to use an app called Rabbit, which not only scanned packages but also told drivers which packages to deliver in which order and provided turn-by-turn directions. But the company began using the in-house app before it was ready, former Amazon employees say. After the app’s launch, Trip O’Dell, a design manager, was tasked with heading a team to make improvements to Rabbit, which he described as a work in progress. “In sort of the typical Amazon way where you will try something then stomp on the accelerator, it often ends up ready, fire, aim.”

O’Dell recruited an idealistic band of designers to Amazon with the pitch that they were going to make life on the road better for drivers. But Paula Wood, a member of this group, quickly became disillusioned with the technology and Amazon’s commitment to drivers. “It was ludicrous to expect drivers to be able to deliver in the tiny slices of time,” Wood said. “They put humans into a machine-oriented system.”

Wood said that on many routes, drivers didn’t have enough time to go to the bathroom or eat, so they skipped meals and breaks and urinated in bottles. Navigation directions were terrible, she said. Drivers were, for example, directed to curbs that were no-stopping zones during rush hour. The Rabbit sent drivers on dangerous paths, back and forth across busy roads, she said, full of repeated U-turns and left turns, like the ones that killed Covey and Acerra.

Research shows left turns can be risky because they require the driver to cross oncoming traffic, and the pillar between the windshield and the door can make it harder to see pedestrians in crosswalks. The algorithm that powers the turn-by-turn directions UPS uses, by contrast, programs out most left turns.

One former Amazon manager recalled watching a driver on a ride-along pounding furiously on the phone while shouting: “I hate this Rabbit! I hate this Rabbit!”

The company said there are “hundreds of technologists at Amazon who are focused on continuously improving the functionality of the Rabbit app” and, based on feedback from drivers and contractors, it has made more than 500 changes this year alone. Amazon added that it has “included functionality to avoid left and U-turns, even if that means a route takes longer” and that drivers “have always been able to stop at any time to take a bathroom break.”

Penny Register-Shaw, a former FedEx lawyer, was hired by Amazon in September 2016 to whip the delivery contractor program into shape, according to four people familiar with the program at the time. One of her first orders of business was to attend the New Jersey summit, where at least one contractor said he felt like at last someone was listening and would present the plight of drivers to Amazon management.

But Register-Shaw had trouble persuading her bosses. She spoke gently and slowly, the cadence of her voice reflecting her Tennessee upbringing, and was interrupted so frequently by her new Amazon colleagues that she rarely finished a sentence, according to several people who worked with her.

Register-Shaw and her team proposed changes to make deliveries safer for both drivers and the public, according to interviews with people familiar with the group. They recommended a drug-testing regimen for contractor drivers who were already on the road. The plan called for random tests “so drivers would not know when they were coming,” said a person familiar with the white paper proposing the tests. But the idea was nixed by higher-ups, according to people familiar with the matter.

Asked about this account, Lunak, the Amazon spokesperson, initially said it was false. But when asked additional questions about the company’s drug-testing practices, she explained that Amazon required “comprehensive” preemployment drug screening and said that drivers “are subject to additional screening if there is reasonable cause or if there is an accident.”

At some delivery stations, drivers had to retrieve their vans from distant lots before picking up their packages, and that often put them behind schedule before they even began their routes, according to two people on Register-Shaw’s team. They said her group pushed for closer parking and when that did not happen, the group recommended that drivers’ travel time be taken into account when planning shifts. That idea did not move forward either.

Members of Register-Shaw’s team were mortified by reports of drivers urinating in bottles rather than taking bathroom breaks, and even defecating outside of customers’ homes. “Humans don’t do that unless they’re under tremendous pressure,” a former member of the team said.

In early 2018, an audit team that Register-Shaw had assigned to evaluate the growing pool of delivery contractors working for Amazon reported that it had discovered dozens of the companies were out of compliance.

Some contractors didn’t have the amount of insurance Amazon required, and others weren’t paying for legally mandated overtime and rest breaks, according to several people familiar with the audit.

The findings posed a problem for Udit Madan, the executive Amazon had just put in charge of its last-mile program, according to people familiar with the audit team’s work. Putting as many drivers on the road as possible every day was a priority for Amazon. In one delivery station, the package count nearly doubled overnight, according to a manager who worked there; the e-commerce giant could ill afford to lose established delivery partners to carry those shipments to the customer.

“You felt the pressure,” said a person close to the audit team. “If you take 200 vans off the street, that would have an impact on the customer promise of two-day delivery.”

Register-Shaw eventually took the fall, resigning rather than firing members of the audit team, according to a person familiar with the matter. The head of the audit team was forced out soon after, and the team was dispersed. When asked to comment about the details in this report, Register-Shaw, who now works for Amazon’s largest retail competitor, Walmart, answered, “I wish I could have done more.”

Amazon disputed aspects of this account, saying that its monitoring of delivery contractors has improved since the leadership reshuffle. “Due to issues with the auditing program at the time, the team was moved to a centralized compliance organization,” Amazon said in a statement. “That move and new leadership, created immediate results, including increasing the scope and rate of the audits.”

Madan did not respond to questions sent through an Amazon spokesperson. The company said it monitors its contractors’ compliance with the law and expects those who are not performing to correct their problems within 30 days or “risk having their contract terminated.”

“Our transportation network is not about anyone working faster than is safe,” Amazon said in a statement. “It’s about processes and our overall operations network coming together to be able to serve customers.”

Caroline Gutman for BuzzFeed News

Vans line up to depart after loading at the South San Francisco Amazon facility.

Stuck in the Mud

In June 2018, Amazon invited the news media to Seattle for an event at a picturesque venue overlooking Elliott Bay. Instead of unveiling a new drone or other high-tech project, Dave Clark, standing in front of a van, announced that the company was rebooting its delivery network, shifting much of its package volume to smaller contractors.

The new firms would manage between 20 and 40 routes apiece, compared with hundreds run by the bigger contractors Amazon had previously signed up. Amazon would make it as easy as possible: It helped new delivery companies with legal paperwork, arranged for leases of new vans emblazoned with the company logo and even recommended preferred vendors to handle insurance and payroll. Would-be entrepreneurs — some with no experience in logistics — rushed to sign up for the program, which handed Amazon even more control over nearly every aspect of delivery while also increasing its financial leverage over the tiny firms.

At the same time the program was gearing up, at Amazon managers were putting the final touches on an ambitious road safety plan, the one that aspired to make the company “the safest last mile carrier in the world.”

The July 2018 document, titled "World Wide Amazon Logistics on Road Safety Plan," emphasized that achieving that goal would require a radical shift in the company’s safety culture. Each delivery station, for example, would have a “number of days safe” sign on the wall, all vehicles would be professionally inspected every year for roadworthiness, prospective hires would face more vetting and Amazon would implement a zero-tolerance policy for serious safety violations.

It also detailed the plan in which instructors from the National Traffic Safety Institute would teach new drivers a “defensive driving curriculum.”

“Training is a critical first step to creating the right culture, building a shared vocabulary, and developing the right behaviors,” the plan said.

Although Amazon managers overseeing delivery initially greeted the goals of the safety plan with enthusiasm, according to one person familiar with the plan, their tune changed as the all-important peak season approached.

Between Thanksgiving and Christmas 2018, Amazon roughly doubled its shipments nationwide from the previous year, surpassing the billion package mark for the first time. The company encouraged its delivery contractors to recruit as many drivers as possible. Amazon for its part hired an additional 3,949 employee drivers in the space of just a few weeks, renting “nearly every van in the United States” for them to drive, internal documents show.

In the end, the peak 2018 season looked very little like what the safety team had laid out in its proposal just four months earlier.

Employees charged with inspecting new delivery stations for safety compliance noted in an internal memo that they had been unable to visit every new station prior to launch. In some stations they did manage to visit during peak season, they were chagrined to discover scenes of chaos: inadequately trained managers, severe understaffing, haphazard traffic flows for delivery vans entering and exiting stations, and packages scattered on the floor.

Many of the stations were little more than tents erected in suburban parking lots, referred to internally as “Carnival” stations. Often, the sites suffered from a shortage of bathrooms, unsanitary working conditions, insufficient heat, a lack of ice scrapers for vehicles and poor drainage, according to internal memos and interviews with current and former Amazon employees. Some stations flooded, drivers and packages were “exposed to wind, rain, and snow,” and some parking lots became mired in thick mud that stranded delivery vans. One memo offered a solution for the mud: Put bags of kitty litter in every van.

Human resources employees complained that they “operated with a skeleton crew” while being tasked with recruiting and hiring thousands of seasonal employees who were subsequently taught how to do their jobs by instructors who “lacked the requisite skills to train someone.”

Last January, various departments within Amazon’s logistics operation shared memos detailing “lessons learned” during 2018’s peak season.

Managers overseeing the delivery contractors lamented that there was still “no current metric to measure safety” among their tens of thousands of drivers. During peak, those managers noted, drivers were frequently caught speeding through parking lots, yet there was no way to hold them accountable.

In a memo filed this past January by the group overseeing delivery contractors, one manager warned, “We need a greater focus on safety.”

A group at Amazon responsible for education and training, meanwhile, reported in its memo that it had fallen far short of its hiring goals for driver trainers. Nearly three weeks after peak season ended, 24 delivery stations still didn’t have any driver training at all, the memo said.

In a statement, Amazon said all delivery drivers are required to undergo training “before they are able to deliver even one package.” The company also said that the use of interim facilities such as Carnival stations is “standard practice” in the logistics industry and that it is currently converting those sites into permanent delivery stations.

Internal Amazon documents show that managers in charge of the delivery contractor program worried that the pressure on the system would only intensify during the 2019 holiday rush, as Amazon planned to build 80 new delivery stations, triple the size of its delivery contractor program, and, in April, make overnight delivery the default option for Prime members.

In a memo filed this past January by the group overseeing delivery contractors, one manager warned, “We need a greater focus on safety.”

Bloomberg / Getty Images

Demonstrators hold signs outside Jeff Bezos's penthouse during a protest in New York City on Dec. 2.

Fantastic Plus

Today, Amazon’s delivery operations are under increasing scrutiny as the press, politicians and Amazon’s own former managers question the company’s aggressive approach to logistics.

Citing the BuzzFeed News and ProPublica investigations on the hidden human toll of Amazon’s delivery network, US Sen. Richard Blumenthal in September lambasted the company. On Twitter he called Amazon “callous,” “heartless,” and “morally bankrupt.”

Amazon’s Clark tweeted back, “Senator you have been misinformed.” He wrote that the company took responsibility for its actions and had requirements for safety, insurance, and “numerous other safeguards for our delivery service partners which we regularly audit for compliance.”

A few days later, Blumenthal and two other senators, Sherrod Brown and Elizabeth Warren, demanded answers from Bezos.

“Innocent bystanders — as young as 9 months old — have lost their lives and sustained serious injuries from drivers improperly trained and under immense pressure by Amazon to meet delivery deadlines,” the senators wrote in a September letter to Jeff Bezos. “It is simply unacceptable for Amazon to turn the other way as drivers are forced into potentially unsafe vehicles and given dangerous workloads.”

In the run-up to this year’s peak season, Amazon has adjusted the benchmarks it uses to monitor the performance of its delivery contractors, introducing new safety metrics, according to interviews with delivery contractors and reviews of scorecards used to measure their performance. For example, Amazon began tracking the use of seatbelts by drivers and incorporating that data into weekly scores for delivery businesses. Data is collected through an app that most drivers must use and that monitors speed, acceleration, and braking, among other metrics.

Every week, Amazon rates the performance of its more than 800 delivery contractors. Those that earn the highest scores — identified by Amazon as “fantastic” or “fantastic plus” — receive bonus pay, which some delivery contractors say can represent the difference between losing money or turning a profit.

In a scorecard from November, safety represented 17% of the total score, compared with 33% for a category labeled “quality.” Amazon said that if a delivery contractor doesn’t have a high combined score in its safety and compliance metrics, it cannot reach “fantastic” or “fantastic plus” overall, and that firms that consistently receive low scores can be threatened with termination or see their routes reduced.

In the end, Bezos didn’t reply to the senators’ letter. Instead, a company lobbyist did. He wrote that Amazon empowered hundreds of small businesses through its delivery contractor program and outlined safety and labor compliance tools that he said went far beyond what’s required by law.

“Safety,” the lobbyist wrote, “is Amazon’s top priority.”

One month after that letter was sent, a contractor delivering Amazon packages in a suburban Chicago townhouse complex turned left on a private drive, striking a toddler who had wandered into a puddle in the roadway.

“She didn’t see him,” said Deputy Chief Ron Wilke of the Lisle Police Department, which is still investigating the crash.

The 23-month-old boy died at the hospital that same day. ●

Amazon’s Next-Day Delivery Has Brought Chaos And Carnage To America’s Streets — But The World’s Biggest Retailer Has A System To Escape The Blame Caroline O'Donovan · Aug. 31, 2019

Amazon Is Firing Its Delivery Firms Following People's Deaths Ken Bensinger · Oct. 11, 2019

Ken Bensinger is an investigative reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in Los Angeles. He is the author of "Red Card," on the FIFA scandal. His DMs are open.

Caroline O'Donovan is a senior technology reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in San Francisco.

James Bandler is a senior reporter covering business and finance at ProPublica

Patricia Callahan is a senior reporter covering business for ProPublica.

Doris Burke is a research reporter at ProPublica.

Last updated on December 24, 2019, at 4:23 p.m. ET