ByJean Lotus

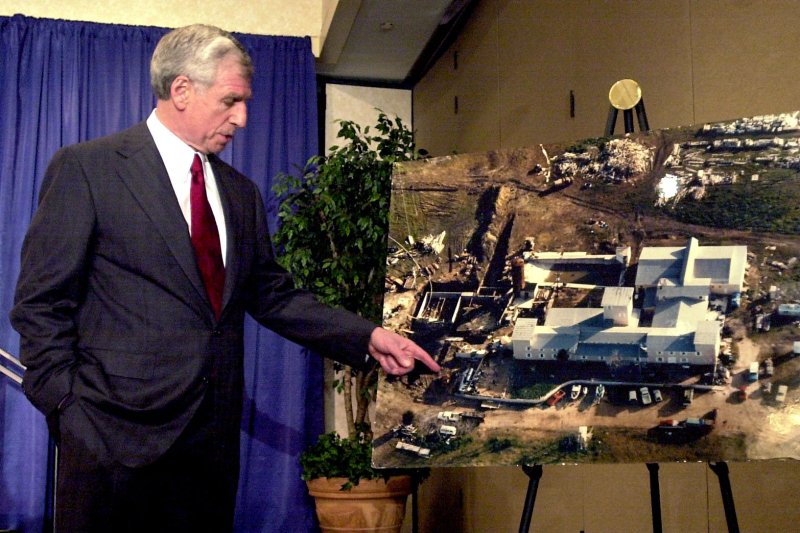

A still shot from the film "Welcome Strangers" shows recently released immigrants in Colorado arriving at Casa de Paz, a hospitality house where they can temporarily stay before traveling to family. Photo courtesy of "Welcome Strangers"

DENVER, Feb. 28 (UPI) -- The plight of immigrants stranded far from home after being released from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention near Denver is the focus of a new independent film that shows how volunteers come to their aid.

Welcome Strangers, a short that premiered this month at Montana's Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, explores immigrants' vulnerabilities when they leave an ICE detention center with little other than the clothes on their backs and a bag of paperwork.

The film focuses on volunteers at Casa de Paz, a Denver-area organization that helps immigrants who just have been been released from the 1,800-bed privately run GEO Group facility in Aurora, Colo.

"Immigrants are released out the back door of the detention center at night, with no identification, food or money," said Garret Savage, the film's producer. "Volunteers and citizens have recognized this problem and show up every night to pick them up."

RELATED Homeland Security: Tensions rising in crowded migrant detention facilities

Released detainees can stay at the Casa de Paz house in Aurora for up to three days while they contact family members, eat home-cooked meals, take hot showers and arrange transportation to their ultimate destination, founder Sarah Jackson said. Jackson owns and lives in the house.

"You could be overjoyed you're finally free, and yet you are frozen in fear because you just don't know what to do," Jackson told UPI. "It just boils down to the fact that immigrants are released from detention, and it's nobody's responsibility to make sure the person gets to where they need to go."

The GEO Group detention center is situated in an industrial park. The film shows volunteers approaching detainees standing in the dark, asking them if they need help.

Released detainees can stay at the Casa de Paz house in Aurora for up to three days while they contact family members, eat home-cooked meals, take hot showers and arrange transportation to their ultimate destination, founder Sarah Jackson said. Jackson owns and lives in the house.

"You could be overjoyed you're finally free, and yet you are frozen in fear because you just don't know what to do," Jackson told UPI. "It just boils down to the fact that immigrants are released from detention, and it's nobody's responsibility to make sure the person gets to where they need to go."

The GEO Group detention center is situated in an industrial park. The film shows volunteers approaching detainees standing in the dark, asking them if they need help.

RELATED Nationwide protests demand closure of migrant detention centers

Many of the immigrants do need help, although ICE contends that detainees have resources to make plans for after they're released.

"The [GEO Group] lobby is open 24/7 and people will choose to wait there when it's cold," Alethea Smock, public affairs officer in the Denver ICE office, said in an email. Detainees have access to phones to call their home consulates, she said.

But volunteers say detainees are released in the clothes in which they were arrested, sometimes even pajamas.

Many of the immigrants do need help, although ICE contends that detainees have resources to make plans for after they're released.

"The [GEO Group] lobby is open 24/7 and people will choose to wait there when it's cold," Alethea Smock, public affairs officer in the Denver ICE office, said in an email. Detainees have access to phones to call their home consulates, she said.

But volunteers say detainees are released in the clothes in which they were arrested, sometimes even pajamas.

RELATED ICE deports survivor of New Orleans hotel collapse

"They're shoved out the back door at night after their attorney's office is closed, with paperwork and left to figure out their next move," said Carmen Mireles, who coordinates immigrant cases for a Longmont, Colo., law firm.

"Thank God for Casa de Paz, because they send a volunteer to the detention center every night without fail," Mireles said.

U.S. Rep. Jason Crow, D-Aurora, battled for access to the GEO Group facility last year. His staffers now tour it twice a month.

"ICE officers will give a heads up to Casa about how many people are being released, and the detainees know to look our for Casa volunteers either at the facility or a gas station nearby," said Anne Feldman, Crow's local spokeswoman.

Casa de Paz director Jackson, who works during the day at a software company, coordinates hundreds of volunteers, who donate clothing, toiletries and frequent flyer miles and prepare hot meals. They also visit detainees and accompany them to the airport.

"Sarah is my angel," volunteer Oliver, a Cameroon native, said in the 21-minute film. Oliver spent six months in detention until he was granted political asylum and was released from GEO Group -- knowing nothing about Colorado, he said. The film shows the reunification of Oliver with his daughter and wife, who had been held in California.

Another immigrant, Javier, released on an asylum petition, makes a phone call to his wife and son in Mexico in the film. He told U.S. officials he had been beaten by gangs in Mexico.

"To the men who beat me, I am a dead man," he said in the documentary.

But Javier worried that his remaining family members were in danger. He had been in detention for three months without speaking to family.

In the past eight years, 2,903 visitors have stayed at Casa de Paz. These include immigrants seeking asylum, those who have been released on bail and detainees' family members. They came from 73 countries, including those in Central America, Cameroon, Fiji, Haiti, India, Italy, Mexico, Nepal, Sudan and Vietnam.

"What we're doing is quite simple and basic, giving things that are not difficult like a meal, a ride to the airport," Jackson said.

Shuffling detained immigrants between facilities across the country makes it harder to comply with court orders in their home states, advocates say.

"It's a logistical nightmare," Denver area immigration attorney Tiago Guevara said. "The government relocates you hundreds of miles from where you live, detaining you for several months so you can't work, and then releases you essentially homeless."

In Colorado, ICE also confiscates passports and IDs, making it difficult for detainees to pass through Transportation Security Administration checkpoints at the airport when trying to get home in time to meet court dates, he said.

Jackson said the environment for immigrants is more difficult than it was a year ago. Some guests are so anxious they won't even take a walk around the block, fearing they will picked up again by ICE, she said.

"It's just continually getting harder and harder to deal with the reality that our country is increasingly becoming more fearful of the 'other,'" she added.

"For a lot of the guests who come to the Casa, they fled trauma, persecution, death and other horrors. And then our government welcomes them with more terror to put them through -- it's just not necessary," Jackson added.

Jackson and Casa de Paz also created an interactive traveling exhibit that was displayed at a 2019 Denver-area TEDx event called Julia's Journey. The exhibit depicts the path of an asylum-seeking mother who stayed at Casa de Paz with her child after being held at the privately run GEO Group center.

"Immigrant detention has become a money-making business, and you can feel pretty depressed about it," Jackson said.

Capturing the human emotions of both immigrants released from detention and the volunteers who help them was the goal of filmmakers, Savage said.

Filmmakers plan grass-roots screenings near other U.S. detention centers.

"We want to show the film to people who may have one idea of what an immigrant looks like in their head," Savage said.

"They might have an idea that an immigrant is a lawbreaker who should not be helped, but not everyone is in detention because they committed a crime. Many are seeking asylum and escaping from trauma in their own countries."

Casa de Paz's mission has also opened the eyes and hearts of hundreds of volunteers, Jackson said.

"You don't need a lot of resources, but if we all give a bit, we can make a big difference. It gives us an experience of seeing our humanity through the eyes of a stranger."