I GIVE IT FOUR OUT OF FIVE STARS

Billion Dollar Brain (1967)

Rating: ★★

UK. 1967.

Crew

Director – Ken Russell, Screenplay – John McGrath, Based on the Novel by Len Deighton, Producer – Harry Saltzman, Photography – Billy Williams, Music – Richard Rodney Bennett, Music Conductor – Marcus Dods, Special Effects – Kit West, Makeup – Benny Royston & Freddie Williamson, Production Design – Syd Cain. Production Company – Jovera S.A.

Cast

Michael Caine (Harry Palmer), Karl Malden (Leo Newbigen), Ed Begley (General Midwinter), Francoise Dorleac (Anya), Oscar Homolka (Colonel Stok), Guy Doleman (Colonel Ross), Vladek Sheybal (Dr Eiwort), Milo Sperber (Basil)

Plot

Secret agent Harry Palmer has quit MI5 and is now working not very successfully as a private detective. He receives a telephone call from a computer that gives him the cryptic assignment to deliver a flask of eggs to a Dr Kaarna in Helsinki. When he arrives, Harry finds that Kaarna has been murdered and in his place is Harry’s old friend, the American Leo Newbigen. Harry is forcibly recruited back by his old MI5 boss and told that the eggs contain a deadly virus. He is ordered to investigate the activities of an organization known as Crusade for Freedom. Travelling between Latvia, Moscow and Texas, Harry discovers that behind Crusade for Freedom is Texan oil billionaire General Midwinter who has harnessed a super-computer (his “billion dollar brain”) to plan a revolution in Latvia with the intent of bringing down the Soviet Union.

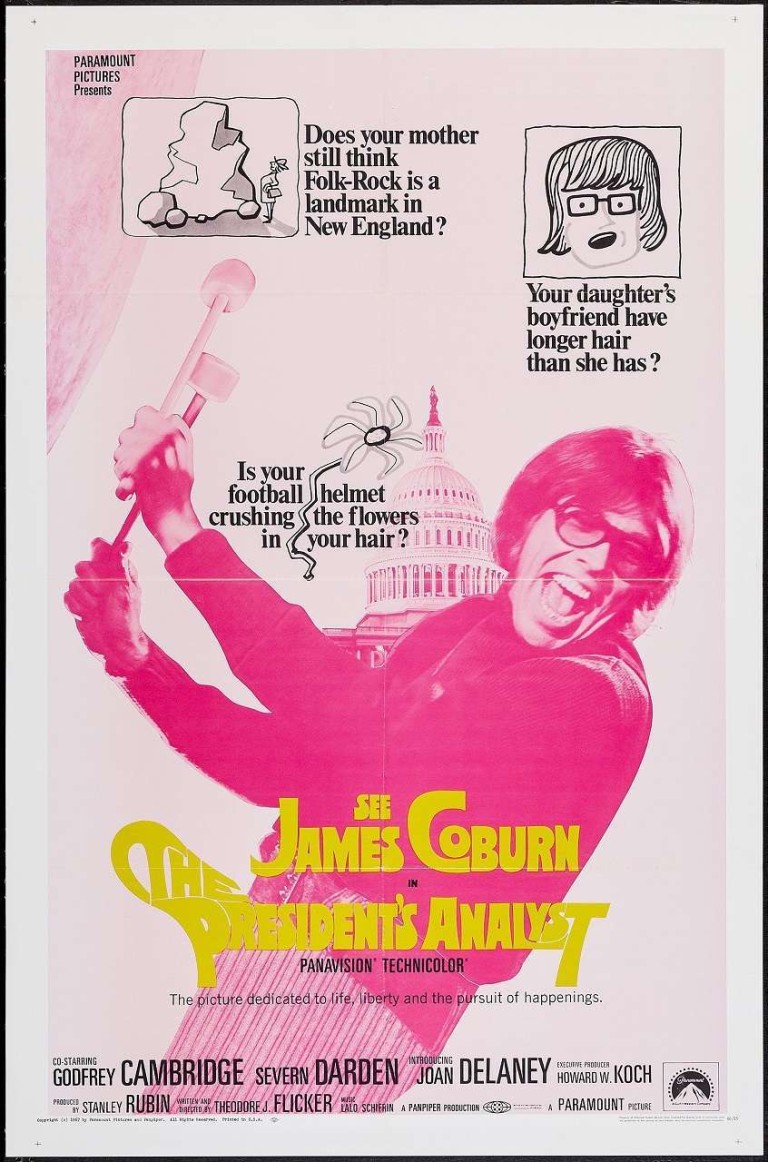

When the James Bond films became a phenomenon in the mid-1960s, dozens of imitators followed. The most prolific of these were absurd comic spectacles such as the Matt Helm films with Dean Martin – The Silencers (1966), Murderers Row (1966), The Ambushers (1967) and The Wrecking Crew (1969) – and the more amusing Our Man Flint films with James Coburn – Our Man Flint (1966) and In Like Flint (1967). There were a great many imitators in this comically silly vein. Amid these, there was a far less substantial body of serious spy films such as The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965), The Deadly Affair (1967) and The Quiller Memorandum (1967).

The Harry Palmer films offered a marriage between the two approaches, casting Michael Caine as a cheeky bespectacled womanising Cockney spy but also placing him into a realistic milieu. Billion Dollar Brain was the third of the Harry Palmer films, following the non-genre The Ipcress File (1965) and Funeral in Berlin (1966). (These were followed thirty years later by two made-for-cable follow-ups, Bullet to Beijing (1995) and Midnight in St Petersberg (1996), in which Michael Caine again reprised the role). The films were based on a series of books by Len Deighton, a writer who regularly specialises in spy fiction. (In an interesting piece of trivia, the spy hero who always narrates in the first person in the books was left unnamed by Len Deighton but was given the name of Harry Palmer in the films and this is something that the series of books have now come to be generically known as).

The Harry Palmer series was produced by Harry Saltzman, the co-producing partner with Albert R. Broccoli of all the James Bond films up until The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). Saltzman developed an interest in creating a more realistic alternative to James Bond after hiring Len Deighton to write the initial (subsequently abandoned) script for From Russia with Love (1963). (Len Deighton also later wrote the script for the legendary unmade James Bond film Warhead).

Billion Dollar Brain was also the second film to be directed by Ken Russell. Russell had previously made the obscure French Dressing (1963), as well a number of highly acclaimed tv plays and documentaries about various composers and artists for the BBC. Alas, Ken Russell is the wrong director for this type of spy thriller, which makes a virtue out of a more realistic milieu than the fantasy world of the Bond films.

The other Harry Palmer films scaled the extravagantly unreal excesses of the Bond films back to the tightly wound, real world espionage plotting as patented by John Le Carré. By contrast, Billion Dollar Brain is surely the Harry Palmer series’ equivalent of a Roger Moore era James Bond film. It is certainly the biggest budgeted of all the Harry Palmer films and sees the series trying to compete in the same arena as contemporary Bond films like Thunderball (1965) and You Only Live Twice (1967), offering up huge sets, lavish action set-pieces and a mad super-villain.

You cannot deny that Billion Dollar Brain is visually an extremely impressive film. The Helsinki locations, which stand in both for themselves as well as Latvia and Moscow, are photographed with a widescreen flourish. There are some fine sets, particularly the huge control room that houses the title super-computer. The climactic scenes with racing steam trains, buzzing snowmobiles, missiles disguised in oil tankers and an army in white snow camouflage gear heading into action, before the tankers are shot down and swallowed up in a collapsing iceflow, is easily on a par with the production work for some of the Bond films of the same era. Certainly, Billion Dollar Brain is free of the schoolboyish smuttiness and lunatic excesses that characterized much of Ken Russell’s subsequent films, but it also has a giddy extravagance that the other Harry Palmer films do not.

Where the film bogs down is in a plot where it is often not clear what is happening. Things seem to happen without reason – you are not sure why Karl Malden suddenly receives order to assassinate his girlfriend Francoise Dorleac; why Vladek Sheybal’s scientist decides to kill himself; or why the Latvian rebels are raiding Soviet trucks (in scenes that seem mounted by Ken Russell as a slapstick caper). These are eventually explained but up until the point they are you have the feeling of being inside a giant juggernaut, moving from location to location and operating on a set of rules that are never communicated to the audience.

Most noticeably, the computer that heavily features, is even referred to in the title, is of little relevance to the film. There is an impressive opening – with it calling Michael Caine in the middle of the night, giving him an assignment and asking him to make Yes/No responses. While it seems clear that the filmmakers were trying to appropriate elements from the Space Age, the computer never actually does anything. All of its operations are simple substitutions for standard spy antics – issuing orders, filing information. It is never harnessed for extra computational power and certainly comes nowhere near the science-fictional artificial intelligence that the publicity machine tried to pump it up into being. Nor is it ever explained how the machine is crucial to General Midwinter’s plan to overthrow the Soviet Union.

Michael Caine never managed to look more devilishly sexy than he was in the Harry Palmer films, outfitted in an unappealing set of horn rim glasses while drifting through the spectacle with cheerful Cockney cheekiness. Although, amidst all the spectacle of the latter half, Caine’s playing gets lost – unlike the other Harry Palmer films, he plays a distinct supporting part to the show. Ed Begley [Sr] gives an OTT performance as General Midwinter, something that seems to be trying to be coming close to a Bond villain, where he is serviced by some amusingly well written speeches. Oscar Homolka steals much of the film with his sly performance as an unexpectedly friendly Russian general. In the before-they-were-famous category, one can see a young Donald Sutherland in a role as a computer technician who issues a warning into a telephone and Susan George as a Russian girl on the train.

The look of the bespectacled Cockney spy was later borrowed by Michael Myers in his spy film spoof Austin Powers, International Man of Mystery (1997) and sequels. In a nice touch, Michael Caine was cast as Austin Powers’ father in Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002). One of the running gags in Austin Powers was of people standing or placing objects in front of others when they are naked, although you can see that this was actually patented here with Michael Caine standing in various convenient positions to hide Francoise Dorleac’s nudity during the bathhouse scenes.

The only other Len Deighton work of genre note adapted to the screen was the tv mini-series SS-GB (2017) based on his 1978 novel, an alternate history detective story set in an England that is occupied by Nazis after they won World War II. There was also the non-genre tv mini-series Game, Set, and Match (1988), based on Deighton’s Bernard Samson series of spy novels. The only other film work Deighton was involved with is as producer of the musical satire Oh, What a Lovely War! (1969) but he was so dissatisfied with the process that he had his name removed.

Ken Russell’s other films of genre interest are:– the historical witch persecution film The Devils (1971); the deranged adaptation of The Who’s rock opera Tommy (1975); the mind-bending sf film Altered States (1980); the psycho-sexual thriller Crimes of Passion (1984); Gothic (1986), centred around the events leading up to the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s writing Frankenstein; the campy Bram Stoker adaptation The Lair of the White Worm (1988); Mindbender (1996), a biopic of the fake psychic Uri Geller; The Fall of the Louse of Usher (2002), Russell’s demented home movie take on Edgar Allan Poe; and an episode of the horror anthology Trapped Ashes (2006).

Trailer here

Director: Ken Russell

Category: Science Fiction

Themes: Spy Films, Super-Computers, Artificial Intelligence, Communism and the Cold War, Film Series and Sequels, Films of 1967

MORE VIDEOS:

MORE VIDEOS:

'Caine Below Zero' - the making of Billion Dollar Brain

HarryPalmerMovieSite

A featurette/short 'making of' documentary about the Harry Palmer movie 'Billion Dollar Brain' of 1967 starring Michael Caine. The colour of the 16 mm film was very red so it has been changed into b & w.

The Bafta winning and multi-Oscar nominated British composer Richard Rodney Bennett created a suitably eerie soundtrack for this 1967 Ken Russell take on the harry palmer spy franchise. In this - the third installment in the harry palmer series - michael caine finds himself in the icy wastes of finland, caught up in the machinations of a deranged ant-communist texan billionaire General Midwinter (played superbly by Ed Begley) intent upon destroying the soviet union by invading latvia with his huge private army. The Soviets are out to foil Midwinter's crazy plans however in the shape of the beautiful - and deadly- spy 'Anya', played by Francois Dorleac, who's last movie this would be before her tragic death only a month later in a car accident .

After producing the first two Harry Palmer movies to provide a more realistic, intellectual alternative to his cartoonish James Bond series, producer Harry Saltzman "Bonded" it up for this third entry after THE IPCRESS FILE and FUNERAL IN BERLIN. Although a troubled production with BIG SLEEP-level plot complications and an unlikely director in arthouse favorite Ken Russell, it's considered the liveliest of the Palmer series. Magnetic leading lady Francoise Dorleac (Catherine Deneuve's sister) was killed in an car accident soon after filming completed. As always, find more great cinematic classics at http://www.trailersfromhell.com

FILM STILLS BILLION DOLLAR BRAIN

ALTERNATIVE TRAILER

A short clip from the movie 'Billion Dollar Brain'. It shows the operation of a Honeywell H200 cmputer from the mid 1960s. You would turn on AC, wait for all the cooling fans to spin up, clear core, mounot several 1/2 inch tapes, load the card reader and then you are ready to compute. I maintained and programmed computers like this from 1965 onward.

This is the first computer I ever worked on. I learned how to install and maintain a system like this back in 1965. It had 24K characters of memory, several tape drives, a card reader and a line printer. Random access storage devices were still a few years away for this model.