Stay positive, Scott Morrison: when you berate people for bad behaviour, they do it more

by Peter Bragge and Liam Smith, The Conversation

COVID-19 is a rare moment in time where individual behaviours can have profound impacts on society.

To address some of the negative impacts, politicians are talking to the public using a style familiar to anyone who has looked after children: forceful and direct appeals to stop engaging in unhelpful behaviours.

Take the example of hoarding. A week ago, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said: "Stop hoarding. I can't be more blunt about it. Stop it. … It's one of the most disappointing things I've seen in Australian behaviour in response to this crisis."

Victoria Premier Daniel Andrews and NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian used similar "stop doing this" communication.

Clearly, this is borne out of frustration. But this approach to behaviour change may do more damage than good for three reasons that are well-established in behavioural science: negative normative messaging, paternalistic messaging and untrusted messengers.

Saying 'don't do' something makes the behaviour more likely

It's widely known in the behavioural sciences that our impressions of what other people are doing influence our own behaviour.

In research conducted by leading psychology researchers, including Wes Schultz and Robert Cialdini, people were informed how much energy their neighbours were using to see what the impact would be on their own usage.

Importantly, it influenced high- and low-energy users in different ways—high users reduced their usage, but low users increased theirs.

The lesson here is that people look for signals—both consciously and unconsciously—that tell them what behaviours are normal, and this perception is a powerful influence on their own behaviour.

So when leaders say "stop doing" something, people can interpret this as "lots of people are doing this, otherwise they wouldn't be saying not to" and "because lots of people are doing it, it's a normal thing to do."

So the message can have the opposite effect to what is intended—the undesirable behaviour increases because it is perceived as normal.

One positive-focused campaign that worked

As behavioural researchers, we've used this established principle to craft a successful mass-media public campaign in Victoria.

Several years ago, the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services faced the challenge of unnecessary calls to the 000 emergency call centre rising faster than population growth.

Our background research showed that previous campaigns focusing on "don't do this" messaging caused a rise in unnecessary calls to 000 because it promoted "negative norms".

So, we focused on the opposite—a positive (do this) campaign, Save Lives. Save Ambulances for Emergencies. A follow-up campaign, Meet the Team highlighted alternatives to dialling 000 for minor ailments—pharmacies, the nurse-on-call service and local general practitioners.

These campaigns were successful in shifting attitudes to appropriate ambulance use, leading to changes in the target behaviour - fewer unnecessary calls to 000. Ambulance Victoria CEO Tony Walker said: "In my mind it's helped save lives … We saw a reduction in calls—around 50 less per day and that's 10 ambulances that were therefore available."

Why 'top-down' messaging is ineffective

When politicians frame a message in a paternalistic way to constituents, it can also be ineffective for at least two reasons.

The first is the behaviour politicians are seeking to correct can seem perfectly reasonable and rational to the people doing it. Thus, berating people for such behaviour is likely to be ineffective. (For example, they might say, "my situation is different because…" or "I'm doing it for my family".)

As a result, the message and/or the source would be dismissed. This may lead to people then dismissing future messages from politicians.

Another issue is that messaging done in a "top down" way threatens our autonomy - one of the most important human needs, and one directly related to well-being.

When autonomy is threatened, people react in various ways. These include expressions of distrust ("I don't like it") or doubt ("is this needed?"), avoidance of the message, and—most importantly in the COVID-19 context—efforts to reassert autonomy by defying change.

The paternalistic tone is compounded by the fact that unfortunately, politicians are not the flavour of the month.

Research shows trust of federal and state governments is at an all-time low, with nearly two-thirds of people believing politicians lack honesty and integrity.

And as highlighted in a recent report published by the Australian and New Zealand School of Government, addressing this issue, like COVID-19, is not a "quick fix".

How should the messaging be changed?

So, what should the government be doing differently in its coronavirus messaging? Here are a few simple strategies.

First, emphasise positive behaviours. Thanking people for their good behaviour, which Berejiklian also did in her address, is a good start. This could also draw upon how well communities responded to the summer bushfire crisis. For example, a positive message might say: "Just as in the bushfires, Australians are looking after each other in the COVID-19 response. Many people are heeding advice to stay at home. This is saving lives. "

Second, alter the paternalistic tone to more inclusive language that makes people feel part of the change. Governments and other messengers should amplify messages that say "together, we are fighting a virus to save lives".

Finally, consider other messengers. For example, good proponents for non-hoarding behaviours may be older, well-respected Australians such as retired AFL player Ron Barassi or former Governor-General Quentin Bryce. The voices of respected figures like these may reach people that tune out anything politicians say.

This is an incredibly difficult time for governments and other leaders. They are getting the very best advice from medical experts, based on the best knowledge available, about what behaviours can flatten the curve of coronavirus infections.

Adding insights from behavioural science can help ensure the messages they deliver have the best possible effectWe're running out of time to use Endgame C to drive coronavirus infections down to zero

Provided by The Conversation

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Sunday, March 29, 2020

Coronavirus shines a light on fractured global politics at a time when cohesion and leadership are vital

by Tony Walker, The Conversation

Leaders of the world's largest economies came together at a virtual G20 this week to "do whatever it takes to overcome the coronavirus pandemic". But the reality is that global capacity to deal with the greatest challenge to international well-being since the second world war is both limited and fractured.

A G20 statement at the end of a 90-minute hookup of world leaders said the right things about avoiding supply-chain disruptions in the shipment of medical supplies, and their agreement to inject A$8.2trillion into the global economy.

By all accounts, interactions between the various players were more constructive than previous such gatherings in the Donald Trump era.

However, emollient words in the official statement, in which the leaders pledged a "common front against this common threat", could not disguise deep divisions between the various players.

The US and China might have acknowledged the need for coordinated action to deal with the pandemic and its economic consequences, but this hardly obscures the rift between the world's largest economies.

While Trump says he and Chinese President Xi Jinping have a good relationship, the fact remains Washington and Beijing are at loggerheads over a range of issues that are not easily resolved.

These include trade in all its dimensions. And central to that is a technology "arms race".

Then there is Trump's persistent—and deliberately provocative—reference to a "Chinese virus". Beijing has strongly objected to this characterisation.

Overriding all of this is China's quest for global leadership in competition with the US and its allies. The US and its friends see this quest as both relentless and disruptive.

In its response to the coronavirus pandemic, which originated in China's Hubei province, Beijing has sought to overcome world disapproval of its initial efforts to cover up the contagion by stepping up its diplomatic efforts.

In this we might contrast China's approach with that of the Trump administration, which continues to emphasise an inward-looking "America first" mindset.

These nativist impulses have been reinforced by a realisation of America's dependence on Chinese supply chains. The US imports a staggering 90% of its antibiotics from China, including penicillin. America stopped manufacturing penicillin in 2004.

In remarks to pharmaceutical executives earlier this month, Trump said dependence on Chinese pharmaceutical supply chains reinforced the

"importance of bringing all of that manufacturing back to America."

Tepid American support for international institutions like the United Nations and its agencies, including, principally, the World Health Organisation, is not helpful in present circumstances.

Trump's verbal onslaught against "globalism" in speeches to the UN has undermined confidence in the world body and called into question American support for multilateral responses to global crises.

Ragged responses to the coronavirus pandemic are a reminder of the dangers inherent in a world in which global leadership has withered.

In Europe, leaders spent most of Thursday arguing over whether a joint communique would hint at financial burden-sharing to repair the damage to their economies.

Germany and the Netherlands are resisting pressures to contribute to a "coronabonds" bailout fund to help countries like Italy and Spain, hardest hit by the pandemic.

This reluctance comes despite a warning from European Central Bank president Christine Lagarde that the continent is facing a crisis of "epic" proportions.

Resistance to a push by European leaders, led by France's Emmanuel Macron, to collectively underwrite debt obligations risks fracturing the union.

These sorts of geopolitical tensions are inevitable if the pandemic continues to spread and, in the process, exerts pressures on the developed world to do more to help both its own citizens and those less fortunate.

In an alarming assessment of the risks of contagion across conflict zones, the International Crisis Group (ICG) identifies teeming refugee camps in war-ravaged northern Syria and Yemen as areas of particular concern.

In both cases, medical assistance is rudimentary, to say the least, so the coronavirus would not be containable if it were to get a grip.

In its bleak assessment, the ICG says: "The global outbreak has the potential to wreak havoc in fragile states, trigger widespread unrest and severely test international crisis management systems. Its implications are especially serious for those caught in the midst of conflict if, as seems likely, the disease disrupts humanitarian aid flows, limits peace operations and postpones ongoing efforts at diplomacy."

In all of this, globalisation as a driver of global growth is in retreat at the very moment when the world would be better served by a "globalised" response to a health and economic crisis.

These challenges are likely to far exceed the ability of the richest countries to respond to a global health emergency.

The disbursement of A$8.2trillion to stabilise the global economy will likely come to be regarded as a drop in the bucket when the full dimensions of a global pandemic become apparent.

In the past day or so the United States became the country hardest hit by coronavirus, surpassing China and Italy.

Medical experts contend the spread of coronavirus in the US will not peak for several weeks. This is the reality Trump appears to have trouble grasping.

Leaving aside the response of countries like the US, China, Italy, Spain and South Korea, whose health systems have enabled a relatively sophisticated response to the virus, there are real and legitimate concerns about countries whose healthcare capabilities would quickly become overburdened.

In this category are countries like Pakistan, India, Indonesia and Bangladesh, which is housing some 1 million Rohingya refugees.

Questions that immediately arise following the "virtual" leaders' summit are:

- How would the world cope with a raging pandemic that is wiping out tens of thousands in places like Syria and Yemen?

- What body will coordinate the $8.2trillion to stabilise the global economy?

- What role will the International Monetary Fund play in this rescue effort?

- What additional resources might be allocated to the World Health Organisation to coordinate a global effort to withstand a health tsunami?

The short answer to these questions is that the world is less well-equipped to deal with a crisis of these dimensions than it might have been if global institutions were not under siege, as they are.

The present situation compares unfavourably with the G20 responses to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008/9. Then, American leadership proved crucial.

In this latest crisis, no such unified global leadership has yet emerged.

The further splintering of an international consensus and retreat from a globalising world as individual states look out for themselves may well prove one of the enduring consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. This would be to no-one's particular advantage, least of all the vulnerable

Three countries have kept coronavirus in check; here's how they did itVietnam. South Korea. Taiwan.

by Dennis Thompson

by Dennis Thompson

Seoul, South Korea

All three countries are placed uncomfortably close to China, the initial epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic that's now swept across the world.

But they also have one other thing in common: They've each managed to contain their COVID-19 infections, preventing the new coronavirus from reaching epidemic proportions within their borders.

How did they did so might provide lessons to the United States and elsewhere, experts say.

Reacting early was key.

South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam each recognized the novel coronavirus as a threat from the outset, and aggressively tested suspected cases and tracked potential new infections, public health experts said.

"Finding cases and isolating them so they're not transmitting forward—that's the tried and true way of controlling an infectious disease outbreak, and when you analyze what was done in many Asian countries, you will find that at its core," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

The first cases of what is now called COVID-19 appeared in Wuhan, China, in early to mid-December, linked to a live animal and seafood market located next to a major train station.

Most of the world took a watch-and-wait approach, but not Vietnam, said Ravina Kullar, an infectious diseases researcher and epidemiologist with Expert Stewardship Inc. in Newport Beach, Calif.

"They actually started preparing for this on Dec. 31. They were testing on Dec. 31," Kullar said. "They were proactive, and that I think is a key to preventing epidemics. They were overly cautious, and that really benefited the country."

Vietnamese government officials also began hosting press conferences at least once a day, where they supplied honest and forthright information about the status of the coronavirus.

"They were very open and honest with the citizens of Vietnam, and that really served them well," Kullar said.

There have been just 153 confirmed cases in Vietnam, which has a population of more than 96 million, according to Johns Hopkins coronavirus tracking.

A lack of testing in other countries has led to the widespread implementation of authoritarian measures like lockdowns to prevent the spread of coronavirus, Adalja noted.

"If you don't have the diagnostic testing capacity, there may be a tendency to use very blunt tools like shelter-in-place orders, because you don't know where the cases are and where they aren't," Adalja said.

South Korea initiated a system of patient "phone booths" to help people get quickly and safely tested for COVID-19, Kullar said.

"One person at a time can enter one side of this glass-walled booth, they grab a handset, and they are connected with a hospital worker standing on the other side of the glass," Kullar said.

Using a pair of rubber gloves set into the wall, the health care worker can swab the patient without potentially exposing themselves to the virus, Kullar said.

"The hospital is able to tell the patient their results within seven minutes. We don't have anything like that at all," Kullar said. "They had this quickly put in place in most hospitals to get patients swabbed in a way where you don't have direct contact with a health care worker."

A country of 50 million, South Korea currently has 9,241 confirmed cases of COVID-19. While cases continue to climb there, they have done so with a much more gradual slope in March after a steep spike in February.

South Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan all learned lessons from the 2003 SARS epidemic and built up their public health infrastructure to be able to immediately respond to future crises, experts said.

Just 81 miles from mainland China, Taiwan had every reason to become a hotbed of COVID-19 activity. There's a regular and steady flow of population between the island and China.

But there only have been 252 confirmed cases among the island's 23 million citizens.

As with Vietnam, Taiwan began screening passengers flying in from Wuhan as early as Dec. 31, according to the Asia Times.

The island expanded its screening within a week to include anyone who recently traveled to either Wuhan or the Hubei province in which the city is located.

Taiwan also instituted border controls, quarantine orders and school closures, and set up a command center for quick communication between local governments and their citizens.

Although the United States missed its chance to head off a COVID-19 epidemic, and is well on its way to becoming the pandemic's new epicenter, these lessons drawn from other countries could still be used to help manage infections in the months and years ahead, Adalja and Kullar said.

Public health measures like quick testing and contact tracing need to be in place and ready to go by the time states start to lift their lockdowns, Adalja said.

"There is going to be a point where we have to start thinking about how we move forward into a next phase of the response, and that will be finding cases and isolating them," Adalja said. "As part of that, we will need to have diagnostic testing hopefully at the point of care to be able to identify those patients. We missed the early opportunity to do this, but we do have the ability to do that now as we go into a different phase of the response."

The experience in Taiwan and South Korea show that democracies can respond effectively to an epidemic, Kullar noted. And China, with its totalitarian regime, has seen no new cases of local spread in almost a week.

Another example, and a European one at that, is Germany. Although the country has the world's fifth-highest number of confirmed cases (43,646), there only have been 239 deaths.

Kullar cited the German health care system as the reason why people are surviving the virus, in particular the country's nursing corps.

"They have 13 nurses per 1,000 people, which is some of the highest than any of the other heavily affected COVID-19 countries," Kullar said. "The higher number of nurses show that nurses are the backbone of the hospitals, especially in ICU care. They've made sure to really focus in on patient management and survival."Follow the latest news on the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak

More information: Johns Hopkins University has more about COVID-19 case tracking.

But they also have one other thing in common: They've each managed to contain their COVID-19 infections, preventing the new coronavirus from reaching epidemic proportions within their borders.

How did they did so might provide lessons to the United States and elsewhere, experts say.

Reacting early was key.

South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam each recognized the novel coronavirus as a threat from the outset, and aggressively tested suspected cases and tracked potential new infections, public health experts said.

"Finding cases and isolating them so they're not transmitting forward—that's the tried and true way of controlling an infectious disease outbreak, and when you analyze what was done in many Asian countries, you will find that at its core," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

The first cases of what is now called COVID-19 appeared in Wuhan, China, in early to mid-December, linked to a live animal and seafood market located next to a major train station.

Most of the world took a watch-and-wait approach, but not Vietnam, said Ravina Kullar, an infectious diseases researcher and epidemiologist with Expert Stewardship Inc. in Newport Beach, Calif.

"They actually started preparing for this on Dec. 31. They were testing on Dec. 31," Kullar said. "They were proactive, and that I think is a key to preventing epidemics. They were overly cautious, and that really benefited the country."

Vietnamese government officials also began hosting press conferences at least once a day, where they supplied honest and forthright information about the status of the coronavirus.

"They were very open and honest with the citizens of Vietnam, and that really served them well," Kullar said.

There have been just 153 confirmed cases in Vietnam, which has a population of more than 96 million, according to Johns Hopkins coronavirus tracking.

A lack of testing in other countries has led to the widespread implementation of authoritarian measures like lockdowns to prevent the spread of coronavirus, Adalja noted.

"If you don't have the diagnostic testing capacity, there may be a tendency to use very blunt tools like shelter-in-place orders, because you don't know where the cases are and where they aren't," Adalja said.

South Korea initiated a system of patient "phone booths" to help people get quickly and safely tested for COVID-19, Kullar said.

"One person at a time can enter one side of this glass-walled booth, they grab a handset, and they are connected with a hospital worker standing on the other side of the glass," Kullar said.

Using a pair of rubber gloves set into the wall, the health care worker can swab the patient without potentially exposing themselves to the virus, Kullar said.

"The hospital is able to tell the patient their results within seven minutes. We don't have anything like that at all," Kullar said. "They had this quickly put in place in most hospitals to get patients swabbed in a way where you don't have direct contact with a health care worker."

A country of 50 million, South Korea currently has 9,241 confirmed cases of COVID-19. While cases continue to climb there, they have done so with a much more gradual slope in March after a steep spike in February.

South Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan all learned lessons from the 2003 SARS epidemic and built up their public health infrastructure to be able to immediately respond to future crises, experts said.

Just 81 miles from mainland China, Taiwan had every reason to become a hotbed of COVID-19 activity. There's a regular and steady flow of population between the island and China.

But there only have been 252 confirmed cases among the island's 23 million citizens.

As with Vietnam, Taiwan began screening passengers flying in from Wuhan as early as Dec. 31, according to the Asia Times.

The island expanded its screening within a week to include anyone who recently traveled to either Wuhan or the Hubei province in which the city is located.

Taiwan also instituted border controls, quarantine orders and school closures, and set up a command center for quick communication between local governments and their citizens.

Although the United States missed its chance to head off a COVID-19 epidemic, and is well on its way to becoming the pandemic's new epicenter, these lessons drawn from other countries could still be used to help manage infections in the months and years ahead, Adalja and Kullar said.

Public health measures like quick testing and contact tracing need to be in place and ready to go by the time states start to lift their lockdowns, Adalja said.

"There is going to be a point where we have to start thinking about how we move forward into a next phase of the response, and that will be finding cases and isolating them," Adalja said. "As part of that, we will need to have diagnostic testing hopefully at the point of care to be able to identify those patients. We missed the early opportunity to do this, but we do have the ability to do that now as we go into a different phase of the response."

The experience in Taiwan and South Korea show that democracies can respond effectively to an epidemic, Kullar noted. And China, with its totalitarian regime, has seen no new cases of local spread in almost a week.

Another example, and a European one at that, is Germany. Although the country has the world's fifth-highest number of confirmed cases (43,646), there only have been 239 deaths.

Kullar cited the German health care system as the reason why people are surviving the virus, in particular the country's nursing corps.

"They have 13 nurses per 1,000 people, which is some of the highest than any of the other heavily affected COVID-19 countries," Kullar said. "The higher number of nurses show that nurses are the backbone of the hospitals, especially in ICU care. They've made sure to really focus in on patient management and survival."Follow the latest news on the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak

More information: Johns Hopkins University has more about COVID-19 case tracking.

Confusion and poor messaging led to hoarding, experts suggest

by Karen Nikos-Rose, UC Davis

Hoarding is wrong, and you should not do it, all our experts agree. But the reasons people are overbuying—and that you cannot always find toilet paper, milk, eggs, and cleaning supplies after several states issued a shelter-in-place order—are complex.

An expert from the Graduate School of Management and a psychiatrist, both from University of California, Davis, each agreed there was some messaging by political leaders and others that scared people into over-buying. They were in conversation with the local KCRA news anchor team about that Wednesday. We also have a law professor who analyzed the law and found that hoarding is not necessarily illegal.

People acting rationally

Don Palmer, professor at the UC Davis Graduate School of Management, has expertise in organizations, and he said his expertise moves around the edges of the current pandemic. He has opined about the hoarding issue recently.

"Commentators often portray people as irrational when they rush to the store and buy everything in sight, calling it 'panic buying.'"

"But in this case," he said, "most people were likely acting rationally."

Consumers got unclear messages

"Public health and political figures issued pronouncements exhorting the public to make sure they had a 30-day supply of necessities.," Palmer said. "So people went out right after the pronouncements and purchased abnormally large quantities of the things they usually purchase. The fact that this mass buying often resulted in rising prices made matters worse. Those who live paycheck to paycheck—and there are many in our society—likely were particularly quick to shop, because they could least afford the rising prices."

He said in a recent interview: "I think the hoarding and the panic buying is a product of a number of things, one of which is the fact that when you are not getting a message which you can trust about the situation, you are left to figure things out on your own. One way to figure things out on your own is to say, "I'm going to imagine the worst.'"

Bad for the community

Dr. Peter Yellowlees, chief wellness officer for the UC Davis health system, and a professor of psychiatry, said in an interview in Salon that the message that isn't getting out is that "we will get through this … And people are going to need to help each other, and one way to help each other is not to hoard large amounts so your neighbors have nothing … ."

Some hoarding may be illegal

Federal law provides for restriction of hoarding, and it may soon come into effect," said Gabriel "Jack" Chin, a professor of law who teaches criminal procedure. "For purposes of national defense, the U.S. Code allows the president to designate certain things as 'scarce materials' and restrict accumulation 'in excess of the reasonable demands of business, personal, or home consumption as he deems necessary,'" he noted.

As it happens, President Trump issued an executive order this week delegating authority to the secretary of Health and Human Services to designate items under that law. The concern, though, is about "personal protective equipment and sanitizing and disinfecting products," Chin said.

Toilet paper might not be covered

If HHS acts, the federal government may be able to take legal action against individuals or corporations who hoard these essential goods. But consumer goods such as toilet paper or food are not likely to be designated as scarce materials, Chin said.

As for buying goods and making a profit on reselling them, the current law only really applies to businesses, not individuals, he explained.

California passed a law after the Northridge earthquake in 1994 against price gouging. It applies during a national, state or local emergency declared based on an outbreak of disease or for almost any other reason, he said. Aimed primarily at businesses, it prohibits them from selling products or services at more than a 10 percent increase of the pre-emergency price, unless the seller can prove that a greater price increase is based on increased cost of goods, labor or materials. The restriction on price increases applies to a wide range of goods and services, including food, emergency supplies, medical supplies, housing, and repair and reconstruction services.

The law, Chin said, does not prohibit hoarding of toilet paper, medicine, food or anything else.

"Overall, it is fair to say that these laws are controversial and hard to enforce, but they appear to be constitutional. They are controversial because there is a general principle in this country that you are allowed to speculate," and sell products for a higher price, he said.

"On the other hand, not everything is a matter of money."

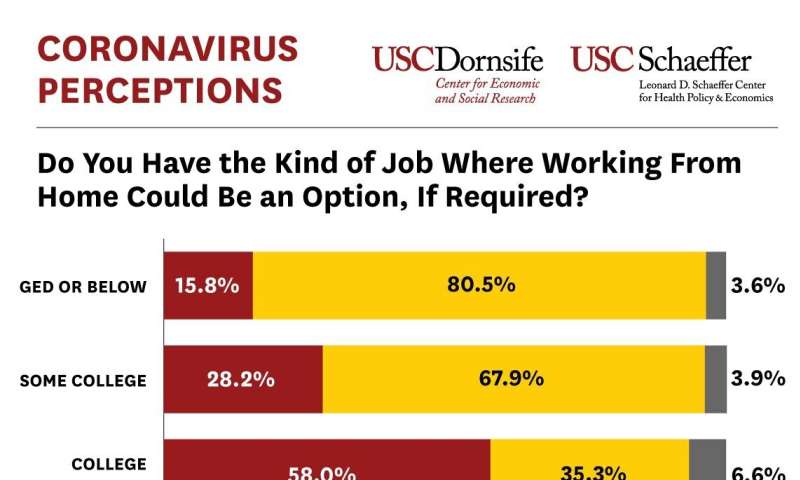

Though the COVID-19 recession may feel different, its victims will look the same

by Stephanie Hedt, University of Southern California

Credit: University of Southern California

The great recession, which hit the world at the end of 2007 affected workers and families in the U.S. in very different ways. Workers with low socioeconomic status (SES) – those with fewer skills and education, as well as racial and ethnic minorities—were especially hurt by the downturn. Foreclosures were concentrated among minorities, and households with lower incomes.

While the COVID-19 pandemic and the impending recession feel unprecedented, one pattern is eerily familiar. Low-SES workers and households are most likely to be hit hardest again. In a survey we conducted in the Understanding America Study between March 10 and March 16, we asked respondents three questions about how the COVID-19 pandemic might affect their work and income. We asked whether their jobs allow them to work from home if required. We also asked how likely they think it is that they will lose their job or run out of money within the next three months.

The figure below shows how the ability to work from home varies by education. Fifty-eight percent of people with a college degree say that working from home is an option, while only 16 percent of respondents with a GED or high school education say that working from home is possible. A similar breakdown by income shows that about 55 percent of respondents with household incomes above $75,000 believe they can work from home if needed. For incomes below $50,000 that it drops to below 30 percent. Comparisons by race show that 42.5 percent of whites have the option of working from home, compared to about 31-32 percent of blacks and Hispanics/Latinos.

While white-collar workers can meet remotely through teleconferences, Slack, email and other applications, many blue-collar jobs require face-to-face and physical interactions that cannot be carried out remotely. Retail clerks and people in vocational trades must be physically present to carry out their jobs. This requirement makes them vulnerable to quarantine restrictions that mandate the closure of non-essential businesses and otherwise limit in-person economic activity.

When asked for the percent chance they we will lose their job as a consequence of the coronavirus epidemic, patterns are very similar. Compared to those with a college degree, workers with a high school education perceive nearly-double the chance they could lose their job in the next three months (13.5% versus 8%). Similarly, workers with household incomes below $25,000 perceived a risk of unemployment that was nearly three times higher than workers with household incomes greater than $75,000 (18.7% versus 6.5%). Whites report an average probability of job loss equal to about 8 percent, while Hispanics/Latinos believe their probability of job loss is more than twice as high (18%).

The pattern is similar, but even more pronounced when asked about the probability of running out of money in three months. For example, among low income households that probability is above 20 percent, while for the highest incomes it is only one third as high, about 7 percent. Whites on average report a probability of running out of money in three months equal to about 10 percent, while blacks think that probability is twice as high (19%), and Hispanics/Latinos report a probability that is two and a half times higher; they believe that on average they have a 25 percent chance of running out of money in three months. We will see whether these perceptions are accurate in the coming months. However, they suggest that COVID-19 is translating into substantially greater economic insecurity for low-SES people.

Of course, there is also a big difference between the effect of the Great Recession and the one triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Great Recession was related to economic imbalances in the housing market, and was not directly about the viability of face-to-face jobs. In the current crisis, the need to work face to face exposes low-SES workers to additional infection risks that high-SES workers can avoid. Disparities in access to healthcare may further compound this pattern. The people who are most vulnerable to the economic effects of the pandemic, are also most likely to have their health compromised as a result.Coronavirus puts casual workers at risk of homelessness

More information: Data cited is available online: uasdata.usc.edu/page/COVID-19+Corona+Virus

'We're trying to keep our heads above water': U.S. healthcare workers fight shortages - and fear

By Kristina Cooke, Gabriella Borter and Joseph Ax Reuters 29 March 2020

A coronavirus testing site outside International Community Health Services during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Seattle

By Kristina Cooke, Gabriella Borter and Joseph Ax

LOS ANGELES/NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. nurses and doctors on the front lines of the battle against the new coronavirus that has infected tens of thousands of Americans and killed hundreds are shellshocked by the damage that the virus wreaks - on patients, their families and themselves.

Nurses and doctors describe their frustration at equipment shortages, fears of infecting their families, and their moments of tearful despair.

NEW YORK CONFIRMED CASES: 53,324. DEATHS: 773

Dr. Arabia Mollette, an emergency medicine physician, has started praying during the cab ride to work in the morning. She needs those few minutes of peace - and some lighthearted banter with the cafeteria staff at Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center in Brooklyn at 6:45 a.m. - to ground her before she enters what she describes as a "medical warzone." At the end of her shift, which often runs much longer than the scheduled 12 hours, she sometimes cannot hold back tears.

"We're trying to keep our heads above water without drowning. We are scared. We're trying to fight for everyone else's life, but we also fight for our lives as well," Mollette said.

The hospitals where she works, Brookdale and St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx, are short of oxygen tanks, ventilators and physical space. Seeing the patients suffer and knowing she might not have the resources to help them feels personal for Mollette, who grew up in the South Bronx and has family there and in Brooklyn.

"Every patient that comes in, they remind me of my own family," she said.

At least one emergency nurse at a Northwell Health hospital in the New York City area is wondering how much longer she can take the strain.

After days of seeing patients deteriorate and healthcare workers and family members sob, she and her husband, who have a young son, are discussing whether she should leave the job she has done for more than a decade.

The emergency room, always a hotbed of frenetic activity, is now dominated by coronavirus cases. There are beds all over the waiting room. The nurse, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said she sees family members dropping off sick relatives and saying goodbye.

"You can't really tell them they might be saying goodbye for the last time," she said.

On Thursday, some nurses and doctors were brought to tears after days of physical and emotional fatigue.

"People were just breaking down," she said. "Everyone is pretty much terrified of being infected ... I feel like a lot of staff are feeling defeated."

At first, she was not too worried about her safety since the coronavirus appeared to be deadliest among the elderly and those with underlying health conditions.

That confidence dissolved after seeing more and more younger patients in serious condition.

"At the beginning, my mentality was, 'Even if I catch it, I'll get a cold or a fever for a couple of days,'" she said. "Now the possibility of dying or being intubated makes it harder to go to work."

There is no official data on the number of healthcare workers who have contracted the virus, but one New York doctor told Reuters that he knew of at least 20.

WASHINGTON STATE CONFIRMED CASES: 4,310. DEATHS: 189

A Seattle nurse has started screening patients for coronavirus at the door of her hospital, a different job from her usual work on various specialty procedures.

She doesn't talk about her new job at home, because she doesn't want to worry her school-aged children, she said. Her husband does not understand her work and tells her to decline tasks that could put her at risk.

"I'm like, 'Well it's already unsafe in my opinion,'" she said.

But she is nervous about having to separate from her family if she contracts the virus.

"I'll live in my car if I have to. I'm not getting my family sick," she said.

The nurse spoke on condition of anonymity because she is not allowed to speak to the media.

During her last shift, she was told to give symptomatic patients napkins to cover their faces instead of masks - and not to wear a mask herself. She ignored that and wore a surgical mask, but she worries less experienced staff heeded the guidance.

"We get right in their faces to take their temperatures because we do not have six-feet-away infrared thermometers," she said. "The recommendations seem to change based on how many masks we have."

Her hospital has put a box outside for the community to donate masks because they are so short of supplies.

She blames the government for not doing more to prepare and coordinate: "People should not have to die because of poor planning."

MICHIGAN CONFIRMED CASES: 4,650. DEATHS: 111

Nurse Angela, 49, says the emergency room at her hospital near Flint, Michigan, is eerily quiet. "We've all been saying this is the calm before storm," said Angela, who asked that only her first name be used.

The patients who trickle in are "very sick" with the COVID-19 respiratory illness, she said, "and they just decline really quickly."

As they go from room to room, the nurses discuss how many things they are contaminating due to their limited protective equipment.

"You'd have to walk around with someone with Clorox wipes all night walking behind you," she said. "The contamination is just so scary for me."

She accepts that she and most of her colleagues may be infected. But she is worried about her daughter and her sister, who are both nurses, and she worries about infecting her 58-year-old husband.

Angela's daughter has sent her three children, including an 18-month-old who suffers from asthma, to stay with their father to avoid possibly infecting them.

"I normally see my grandchildren twice a week and I haven't seen them. It's hard. I just cannot fathom what my daughter's going through," Angela said.

Many of her co-workers have done the same, packing off children to live with relatives because they are terrified, not so much of contracting the disease, but of passing it on.

Some of them are talking about quitting because they feel unprotected.

Angela would not judge them, she said, but she told a friend recently, "You have to remember, what if your kid gets sick or your mom gets sick, who's going to take care of them when you take them to the hospital if all of us just leave?"

(Reporting by Gabriella Borter, Kristina Cooke and Joey Ax; Editing by Ross Colvin and Daniel Wallis)

By Kristina Cooke, Gabriella Borter and Joseph Ax Reuters 29 March 2020

A coronavirus testing site outside International Community Health Services during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Seattle

By Kristina Cooke, Gabriella Borter and Joseph Ax

LOS ANGELES/NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. nurses and doctors on the front lines of the battle against the new coronavirus that has infected tens of thousands of Americans and killed hundreds are shellshocked by the damage that the virus wreaks - on patients, their families and themselves.

Nurses and doctors describe their frustration at equipment shortages, fears of infecting their families, and their moments of tearful despair.

NEW YORK CONFIRMED CASES: 53,324. DEATHS: 773

Dr. Arabia Mollette, an emergency medicine physician, has started praying during the cab ride to work in the morning. She needs those few minutes of peace - and some lighthearted banter with the cafeteria staff at Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center in Brooklyn at 6:45 a.m. - to ground her before she enters what she describes as a "medical warzone." At the end of her shift, which often runs much longer than the scheduled 12 hours, she sometimes cannot hold back tears.

"We're trying to keep our heads above water without drowning. We are scared. We're trying to fight for everyone else's life, but we also fight for our lives as well," Mollette said.

The hospitals where she works, Brookdale and St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx, are short of oxygen tanks, ventilators and physical space. Seeing the patients suffer and knowing she might not have the resources to help them feels personal for Mollette, who grew up in the South Bronx and has family there and in Brooklyn.

"Every patient that comes in, they remind me of my own family," she said.

At least one emergency nurse at a Northwell Health hospital in the New York City area is wondering how much longer she can take the strain.

After days of seeing patients deteriorate and healthcare workers and family members sob, she and her husband, who have a young son, are discussing whether she should leave the job she has done for more than a decade.

The emergency room, always a hotbed of frenetic activity, is now dominated by coronavirus cases. There are beds all over the waiting room. The nurse, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said she sees family members dropping off sick relatives and saying goodbye.

"You can't really tell them they might be saying goodbye for the last time," she said.

On Thursday, some nurses and doctors were brought to tears after days of physical and emotional fatigue.

"People were just breaking down," she said. "Everyone is pretty much terrified of being infected ... I feel like a lot of staff are feeling defeated."

At first, she was not too worried about her safety since the coronavirus appeared to be deadliest among the elderly and those with underlying health conditions.

That confidence dissolved after seeing more and more younger patients in serious condition.

"At the beginning, my mentality was, 'Even if I catch it, I'll get a cold or a fever for a couple of days,'" she said. "Now the possibility of dying or being intubated makes it harder to go to work."

There is no official data on the number of healthcare workers who have contracted the virus, but one New York doctor told Reuters that he knew of at least 20.

WASHINGTON STATE CONFIRMED CASES: 4,310. DEATHS: 189

A Seattle nurse has started screening patients for coronavirus at the door of her hospital, a different job from her usual work on various specialty procedures.

She doesn't talk about her new job at home, because she doesn't want to worry her school-aged children, she said. Her husband does not understand her work and tells her to decline tasks that could put her at risk.

"I'm like, 'Well it's already unsafe in my opinion,'" she said.

But she is nervous about having to separate from her family if she contracts the virus.

"I'll live in my car if I have to. I'm not getting my family sick," she said.

The nurse spoke on condition of anonymity because she is not allowed to speak to the media.

During her last shift, she was told to give symptomatic patients napkins to cover their faces instead of masks - and not to wear a mask herself. She ignored that and wore a surgical mask, but she worries less experienced staff heeded the guidance.

"We get right in their faces to take their temperatures because we do not have six-feet-away infrared thermometers," she said. "The recommendations seem to change based on how many masks we have."

Her hospital has put a box outside for the community to donate masks because they are so short of supplies.

She blames the government for not doing more to prepare and coordinate: "People should not have to die because of poor planning."

MICHIGAN CONFIRMED CASES: 4,650. DEATHS: 111

Nurse Angela, 49, says the emergency room at her hospital near Flint, Michigan, is eerily quiet. "We've all been saying this is the calm before storm," said Angela, who asked that only her first name be used.

The patients who trickle in are "very sick" with the COVID-19 respiratory illness, she said, "and they just decline really quickly."

As they go from room to room, the nurses discuss how many things they are contaminating due to their limited protective equipment.

"You'd have to walk around with someone with Clorox wipes all night walking behind you," she said. "The contamination is just so scary for me."

She accepts that she and most of her colleagues may be infected. But she is worried about her daughter and her sister, who are both nurses, and she worries about infecting her 58-year-old husband.

Angela's daughter has sent her three children, including an 18-month-old who suffers from asthma, to stay with their father to avoid possibly infecting them.

"I normally see my grandchildren twice a week and I haven't seen them. It's hard. I just cannot fathom what my daughter's going through," Angela said.

Many of her co-workers have done the same, packing off children to live with relatives because they are terrified, not so much of contracting the disease, but of passing it on.

Some of them are talking about quitting because they feel unprotected.

Angela would not judge them, she said, but she told a friend recently, "You have to remember, what if your kid gets sick or your mom gets sick, who's going to take care of them when you take them to the hospital if all of us just leave?"

(Reporting by Gabriella Borter, Kristina Cooke and Joey Ax; Editing by Ross Colvin and Daniel Wallis)

Coronavirus: Alameda Health System agrees to pay sick nurses following protest

Alameda Health System agrees workers won’t have to use vacation time if infected treating COVID-19 patients and forced to self-isolate

“I have witnessed the deficiencies of Alameda Health System management, ranging from utter indifference to patient safety to a blatant disregard for their frontline healthcare workers,” Mawata Kamara, an ER nurse in San Leandro, said in a news release. “Any calls for accountability and transparency has been met with silence. It’s clear to us as frontline workers that a systemic change needs to happen immediately if we want to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Alameda Health System agrees workers won’t have to use vacation time if infected treating COVID-19 patients and forced to self-isolate

1 of 18

OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA - MARCH 26: Alameda Health System nurses, doctors and workers hold signs during a protest in front of Highland Hospital on March 26, 2020 in Oakland, California. Dozens of health care workers with Alameda Health System staged a protest to demand better working conditions and that proper personal protective equipment be provided in the effort to slow the spread of COVID-19. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

By DYLAN BOUSCHER | dbouscher@bayareanewsgroup.com | Bay Area News Group

March 29, 2020 at 5:45 a.m.

This story is available to all readers in the interest of public safety.

Frontline workers at Alameda Health System won a significant concession from top management after demanding changes amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Hours after holding a protest outside Highland Hospital in Oakland, a public safety net facility that sees patients regardless of their insurance status, the nurses were assured they won’t have to use vacation time if they become infected at work. The unionized nurses at Alameda Heath System confirmed a key victory on Twitter on Thursday.

The group earlier in the day had been protesting staffing issues and supply shortages at the facility.

Among the staffing issues raised was the practice of nurses not being compensated if they became ill after attending to patients with COVID-19 and having to use vacation time for days spent self-isolating.

Two hours after the workers rallied, CEO Delvecchio Finley announced the hospitals would pay workers exposed to the virus on the clock, according to John Pearson, an emergency room nurse at Highland Hospital. The hospitals will start compensating exposed workers on April 1. But at least two employees exposed before then, an ER tech and nurse at Highland, will not lose vacation time for days spent self-isolating, Pearson said.

“This win is really meaningful to us because it shows that what we’re doing is working and that it’s going to take pressure of workers sticking together just to keep the public safe,” Pearson said. “I’m worried that if we don’t have strong state and federal level resources coming in extremely quickly and on a big scale, that we are not going to be ready for this and the death toll is going to be a lot bigger than it needs to be.”

But the sick time victory proved to be a little hollow on Friday when AHS laid off one of two clinical nurse specialists responsible for teaching health care providers new equipment and techniques.

CEO and Chief Nurse gave our ONLY ER Nurse educator a lay-off notice & are trying to force her into a non union job that’s much worse, exploiting the COVID-19 crisis to water down our training. *PUT THEM ON BLAST:* dfinley@alamedahealthsystem.org jmcinnes@alamedahealthsystem.org pic.twitter.com/THQLRDBHuG

— John Pearson RN (@OaklandNurse) March 27, 2020

Management at the hospitals did not immediately respond to comment.

Negotiations between the union and AHS leaders continue on a contract originally set to expire Tuesday, but an agreement was reached on a one month extension. Health care workers asked the Alameda County Board of Supervisors to retake control of and management over AHS, arguing not doing so could worsen the pandemic outbreak.

Pearson, the chapter president for SEIU Local 1021, the union representing approximately 3,600 Alameda Health System workers at four hospitals and three clinics across the East Bay, has spent the last several weeks asking local and state officials via Twitter to send more personal protective equipment to the facilities.

He said community donations of disinfecting wipes, disposable N-95 masks and gowns, though appreciated, are not enough at Highland, where Pearson said hand sanitizer is also running out, contradicting management reassuring workers there is enough available.

Beyond the statewide lack of medical gloves, gowns, masks and shields, Alameda Health Systems workers raised concerns about a shortage of PAPRs, filtered masks worn by patients undergoing COVID-19 treatment. Two days before the Highland Hospital rally, the union organized a fundraiser on GoFundMe to purchase five more on top of the three the system already owned.

San Leandro Hospital workers said AHS issues are not exclusive to Highland.

OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA - MARCH 26: Alameda Health System nurses, doctors and workers hold signs during a protest in front of Highland Hospital on March 26, 2020 in Oakland, California. Dozens of health care workers with Alameda Health System staged a protest to demand better working conditions and that proper personal protective equipment be provided in the effort to slow the spread of COVID-19. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

By DYLAN BOUSCHER | dbouscher@bayareanewsgroup.com | Bay Area News Group

March 29, 2020 at 5:45 a.m.

This story is available to all readers in the interest of public safety.

Frontline workers at Alameda Health System won a significant concession from top management after demanding changes amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Hours after holding a protest outside Highland Hospital in Oakland, a public safety net facility that sees patients regardless of their insurance status, the nurses were assured they won’t have to use vacation time if they become infected at work. The unionized nurses at Alameda Heath System confirmed a key victory on Twitter on Thursday.

The group earlier in the day had been protesting staffing issues and supply shortages at the facility.

Among the staffing issues raised was the practice of nurses not being compensated if they became ill after attending to patients with COVID-19 and having to use vacation time for days spent self-isolating.

Two hours after the workers rallied, CEO Delvecchio Finley announced the hospitals would pay workers exposed to the virus on the clock, according to John Pearson, an emergency room nurse at Highland Hospital. The hospitals will start compensating exposed workers on April 1. But at least two employees exposed before then, an ER tech and nurse at Highland, will not lose vacation time for days spent self-isolating, Pearson said.

“This win is really meaningful to us because it shows that what we’re doing is working and that it’s going to take pressure of workers sticking together just to keep the public safe,” Pearson said. “I’m worried that if we don’t have strong state and federal level resources coming in extremely quickly and on a big scale, that we are not going to be ready for this and the death toll is going to be a lot bigger than it needs to be.”

But the sick time victory proved to be a little hollow on Friday when AHS laid off one of two clinical nurse specialists responsible for teaching health care providers new equipment and techniques.

CEO and Chief Nurse gave our ONLY ER Nurse educator a lay-off notice & are trying to force her into a non union job that’s much worse, exploiting the COVID-19 crisis to water down our training. *PUT THEM ON BLAST:* dfinley@alamedahealthsystem.org jmcinnes@alamedahealthsystem.org pic.twitter.com/THQLRDBHuG

— John Pearson RN (@OaklandNurse) March 27, 2020

Management at the hospitals did not immediately respond to comment.

Negotiations between the union and AHS leaders continue on a contract originally set to expire Tuesday, but an agreement was reached on a one month extension. Health care workers asked the Alameda County Board of Supervisors to retake control of and management over AHS, arguing not doing so could worsen the pandemic outbreak.

Pearson, the chapter president for SEIU Local 1021, the union representing approximately 3,600 Alameda Health System workers at four hospitals and three clinics across the East Bay, has spent the last several weeks asking local and state officials via Twitter to send more personal protective equipment to the facilities.

He said community donations of disinfecting wipes, disposable N-95 masks and gowns, though appreciated, are not enough at Highland, where Pearson said hand sanitizer is also running out, contradicting management reassuring workers there is enough available.

Beyond the statewide lack of medical gloves, gowns, masks and shields, Alameda Health Systems workers raised concerns about a shortage of PAPRs, filtered masks worn by patients undergoing COVID-19 treatment. Two days before the Highland Hospital rally, the union organized a fundraiser on GoFundMe to purchase five more on top of the three the system already owned.

San Leandro Hospital workers said AHS issues are not exclusive to Highland.

“I have witnessed the deficiencies of Alameda Health System management, ranging from utter indifference to patient safety to a blatant disregard for their frontline healthcare workers,” Mawata Kamara, an ER nurse in San Leandro, said in a news release. “Any calls for accountability and transparency has been met with silence. It’s clear to us as frontline workers that a systemic change needs to happen immediately if we want to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic.”

---30---

Some Kenyan nurses refusing coronavirus patients in protest over gear shortages

By Reuters March 27, 2020

Kenyan nurses wear protective gear during a demonstration of preparations for any potential coronavirus cases at the Mbagathi Hospital, isolation centre for the disease, in Nairobi, Kenya.Reuters

NAIROBI – Nurses in Kenya’s capital and at least two towns have launched protests or refused to treat suspected coronavirus patients because the government has not given them enough protective gear or training, a medical union chief said.

Only a fraction of Kenya’s estimated 100,000 healthcare workers had received any instruction in how to protect themselves, Seth Panyako, the secretary general of the Kenya National Union of Nurses, told Reuters.

Government spokesman Cyrus Oguna said he would check into the reports of the training and protective gear shortages.

Kenya had reported 28 cases of the coronavirus and one death as of Friday. The virus has so far been multiplying across Africa more slowly than in Asia or Europe – but the World Health Organization has warned the continent’s window to curb the infection is narrowing every day.

Nurses in the western Kenyan town of Kakamega and the coastal town of Kilifi ran away when patients with coronavirus symptoms came to their hospitals over the past two weeks, Panyako said on Thursday.

Nurses at Nairobi’s Mbagathi County Hospital went on a go-slow protest last week in protest at a lack of protective gear and training. They feared catching the disease and infecting their families, Panyako said.

“The government is not taking it seriously when health workers run away,” he said.

“My clear message to the government … give them the protective equipment they need.”

Panyako, whose union represents 30,000 health workers, said he had only heard of 1,200 staff getting training in how to protect themselves.

A host of initiatives have sprung up to fill the gaps.

Kenyan start-up Rescue.co, whose Flare app functions as the Uber for private ambulances in Kenya, last week began offering training and protective equipment for the 600 nurses and paramedics using its network.

One paramedic on a course told Reuters he had previously refused to attend a suspected coronavirus patient because he did not have training.

“The team was scared so we didn’t go,” he said, declining to give his name.

Caitlin Dolkart, who co-founded rescue.co, said her company had applied for government permission for trained paramedics to carry out coronavirus tests in patients’ homes.

“They are on the frontlines of responding to patients,” she said. “They have to be protected.”

Plan to divert Chihuahua’s water to US aborted after protests escalate

Protesters set fire to several vehicles belonging to the National Guard and Conagua.

Plan to divert Chihuahua’s water to US aborted after protests escalate

Disgruntled farmers torched 6 vehicles belonging to the National Guard and water commission

Published on Friday, March 27, 2020

The National Water Commission (Conagua) announced on Thursday that it would not divert additional water from a dam in Chihuahua to settle a 220-million-cubic-meter “water debt” with the United States after protests against the diversion turned violent.

Conagua said in a Twitter post Thursday afternoon that it had taken the decision to stop the additional water diversion from the La Boquilla dam due to farmers’ rejection of the move, whose aim was to comply with the 1944 bilateral water treaty between Mexico and the United States.

Chihuahua farmers have long argued that the massive water diversion planned by Conagua would leave them with insufficient water.

On Wednesday night, Conagua doubled the quantity of water being diverted from La Boquilla, located on the Conchos River about 200 kilometers south of Chihuahua city, from 55 cubic meters per second to 110 cubic meters per second.

The water commission’s plan was to divert the additional water to the Rio Grande on the Mexico-United States border for use by the latter country.

The move to increase the water flow out of La Boquilla triggered an aggressive response by farmers on Thursday morning. They set four National Guard vehicles on fire and also torched two Conagua vehicles in Delicias, a city 100 kilometers north of the dam.

The farmers also set up a blockade on federal highway 45 between Delicias and Lázaro Cárdenas, the newspaper Milenio reported. Two members of the National Guard and one farmer were injured in a violent clash there.

A video report by the newspaper El Universal shows disgruntled farmers throwing stones at police and attacking them with large sticks in a separate clash outside the La Boquilla dam.

Farmers have staged several protests against the diversion of water from La Boquilla, and stormed the fenced-off dam precinct on February 4, staging a sit-in until they were removed by the National Guard the next day.

Chihuahua Governor Javier Corral, who announced last month that his government would support the farmers in their fight for water, said in a video posted to Twitter on Friday that he was happy with Conagua’s decision to stop the additional diversion of water from La Boquilla.

He called the decision to open additional sluices at the dam “erratic” and “foolish.”

In a statement released before Conagua’s decision to back down on its diversion plan, the Chihuahua government said the decision to divert additional water from La Boquilla violated agreements the two parties had reached.

Corral said that he wasn’t informed of the decision, as Conagua claimed, and called for the water commission to close the sluices it opened on Wednesday night.

Source: Milenio (sp)

Coronavirus

Mexico’s community of makers is banding together to support the medical response to the growing outbreak of Covid-19.

A health care worker at a hospital in Guanajuato with one of the makers' masks.

Makers community goes to work on protective shields for health workers

More than 300 3D printers are turning out shields to protect workers from Covid-19

Published on Saturday, March 28, 2020

• Full coronavirus coverage here

Using more than 300 3D printers, laser cutters and other tools, at least 250 groups of makers and innovators across the country are dedicating as much time as they can to the manufacture of protective face shields for doctors, nurses and other medical personnel who are currently treating people with coronavirus and are likely to see a much greater influx of patients as the outbreak of the disease worsens.

Groups have formed in Mexico City and states across the country, including Puebla, Michoacán, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Yucatán, Nuevo León and Guerrero, and hospitals in several states have already taken delivery of plastic face masks.

The makers’ work is especially important given that healthcare workers across Mexico protested this week to demand personal protective equipment such as face masks so that their safety is ensured while treating Covid-19 patients.

According to a report by the newspaper El Economista, the makers in Mexico became aware of the need to start making masks after chatting via the internet with their counterparts in countries such as Italy, Spain and the United States, where there have been massive outbreaks of Covid-19 and thousands of deaths.

Many of the designs being used in Mexico were shared by members of the makers’ communities in those countries.

One of the leaders of the efforts in Mexico is Abraham Trujillo, a mechatronics engineer in Acapulco, Guerrero, and head of the México Makers Covid-19 organization, which is coordinating the work of many of the makers’ groups across the country.

He told El Economista that almost 800 people are working with México Makers Covid-19 to produce face masks from sheets of acetate and other materials.

Trujillo said that approximately 700 masks were made with 3D printers this week, 300 of which have already been delivered to hospitals. He explained that the majority of people participating in the mask-making efforts do not usually work in manufacturing jobs.

Trujillo added that México Makers Covid-19 coordinators in states across the country are contacting local hospitals to find out if they need additional masks for their staff. He also said that the office supplies store Lumen has agreed to donate sheets of acetate so that the different groups can make more masks.

The group is also seeking donations from the public of acetate sheets, elastic bands, laser cutters and 3D printers. The group can be contacted via email at donaciones@mexicomakers.org.

A health care worker at a hospital in Guanajuato with one of the makers' masks.

Makers community goes to work on protective shields for health workers

More than 300 3D printers are turning out shields to protect workers from Covid-19

Published on Saturday, March 28, 2020

• Full coronavirus coverage here

Using more than 300 3D printers, laser cutters and other tools, at least 250 groups of makers and innovators across the country are dedicating as much time as they can to the manufacture of protective face shields for doctors, nurses and other medical personnel who are currently treating people with coronavirus and are likely to see a much greater influx of patients as the outbreak of the disease worsens.

Groups have formed in Mexico City and states across the country, including Puebla, Michoacán, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Yucatán, Nuevo León and Guerrero, and hospitals in several states have already taken delivery of plastic face masks.

The makers’ work is especially important given that healthcare workers across Mexico protested this week to demand personal protective equipment such as face masks so that their safety is ensured while treating Covid-19 patients.

According to a report by the newspaper El Economista, the makers in Mexico became aware of the need to start making masks after chatting via the internet with their counterparts in countries such as Italy, Spain and the United States, where there have been massive outbreaks of Covid-19 and thousands of deaths.

Many of the designs being used in Mexico were shared by members of the makers’ communities in those countries.

One of the leaders of the efforts in Mexico is Abraham Trujillo, a mechatronics engineer in Acapulco, Guerrero, and head of the México Makers Covid-19 organization, which is coordinating the work of many of the makers’ groups across the country.

He told El Economista that almost 800 people are working with México Makers Covid-19 to produce face masks from sheets of acetate and other materials.

Trujillo said that approximately 700 masks were made with 3D printers this week, 300 of which have already been delivered to hospitals. He explained that the majority of people participating in the mask-making efforts do not usually work in manufacturing jobs.

Trujillo added that México Makers Covid-19 coordinators in states across the country are contacting local hospitals to find out if they need additional masks for their staff. He also said that the office supplies store Lumen has agreed to donate sheets of acetate so that the different groups can make more masks.

The group is also seeking donations from the public of acetate sheets, elastic bands, laser cutters and 3D printers. The group can be contacted via email at donaciones@mexicomakers.org.

Clemente, right, delivers masks to a hospital in Morelia, Michoacán.

In Guanajuato, two young entrepreneurs who operate an on-demand 3D printing business in the city of León have also turned their focus to producing protective face shields. Omar Ramos and María de la Barrera came up with their own mask design by combining different characteristics of protective shields made by makers in both Italy and Spain.

They have already made several dozen masks that they have distributed to hospitals in León and other Guanajuato cities. Ramos and de la Barrera’s business, impresion3d.mx (Spanish only), is also seeking donations to support their mask-making efforts.

Two other members of the makers’ community supporting the response to Covid-19 are Diego Villegas Orozco and Moisés Clemente Guzmán.

Villegas, a dental surgeon, is acting as a coordinator for mask-making groups in Mexico City and has already delivered a batch of 30-40 masks to six hospitals including La Raza National Medical Center, whose workers have protested a lack of protective equipment twice in the past week.

He told El Economista that just three people had joined the efforts to make plastic face shields by last Sunday but that number grew to 88 during the week. Villegas said that the makers in the capital have the capacity to produce triple the number of masks they made this week (220 approximately) provided they have sufficient materials.

For his part, Clemente, a 3D printing hobbyist, is making face masks in Morelia, Michoacán, where he works for a digital education platform. He has already donated his creations to hospitals in his home state as well as Jalisco, San Luis Potosí and Querétaro.

Clemente said that each mask he makes costs 50 pesos (US $2) to produce, adding that he hoped that other people with access to 3D printers and knowledge about how to use them would also join the mask-making initiative.

Another Mexican supporting the efforts, albeit from afar, is Marco Antonio Castro Cosío, who lives in one of the global hotspots of Covid-19 – New York City.

From the Big Apple, the Jalisco native is helping to establish relationships between hospitals in his home state and makers currently producing face masks. The digital innovation researcher said that his aim is to ensure that Mexican medical personnel have sufficient protective equipment to treat an expected influx of Covid-19 patients.

“It appears that the tsunami will reach us [Mexico] later so we have to prepare. Here in New York, a lot of the makers who want to help can’t find materials anymore because we’re at home [in quarantine] now and the majority of stores are not open,” Castro said.

He added that it makes him “very happy” to see so many people contributing to the efforts to respond to Covid-19 in Mexico, where there were 717 confirmed cases of the disease as of Friday and 12 coronavirus-related deaths.

Source: El Economista (sp)

In Guanajuato, two young entrepreneurs who operate an on-demand 3D printing business in the city of León have also turned their focus to producing protective face shields. Omar Ramos and María de la Barrera came up with their own mask design by combining different characteristics of protective shields made by makers in both Italy and Spain.

They have already made several dozen masks that they have distributed to hospitals in León and other Guanajuato cities. Ramos and de la Barrera’s business, impresion3d.mx (Spanish only), is also seeking donations to support their mask-making efforts.

Two other members of the makers’ community supporting the response to Covid-19 are Diego Villegas Orozco and Moisés Clemente Guzmán.

Villegas, a dental surgeon, is acting as a coordinator for mask-making groups in Mexico City and has already delivered a batch of 30-40 masks to six hospitals including La Raza National Medical Center, whose workers have protested a lack of protective equipment twice in the past week.

He told El Economista that just three people had joined the efforts to make plastic face shields by last Sunday but that number grew to 88 during the week. Villegas said that the makers in the capital have the capacity to produce triple the number of masks they made this week (220 approximately) provided they have sufficient materials.

For his part, Clemente, a 3D printing hobbyist, is making face masks in Morelia, Michoacán, where he works for a digital education platform. He has already donated his creations to hospitals in his home state as well as Jalisco, San Luis Potosí and Querétaro.

Clemente said that each mask he makes costs 50 pesos (US $2) to produce, adding that he hoped that other people with access to 3D printers and knowledge about how to use them would also join the mask-making initiative.

Another Mexican supporting the efforts, albeit from afar, is Marco Antonio Castro Cosío, who lives in one of the global hotspots of Covid-19 – New York City.

From the Big Apple, the Jalisco native is helping to establish relationships between hospitals in his home state and makers currently producing face masks. The digital innovation researcher said that his aim is to ensure that Mexican medical personnel have sufficient protective equipment to treat an expected influx of Covid-19 patients.

“It appears that the tsunami will reach us [Mexico] later so we have to prepare. Here in New York, a lot of the makers who want to help can’t find materials anymore because we’re at home [in quarantine] now and the majority of stores are not open,” Castro said.

He added that it makes him “very happy” to see so many people contributing to the efforts to respond to Covid-19 in Mexico, where there were 717 confirmed cases of the disease as of Friday and 12 coronavirus-related deaths.

Source: El Economista (sp)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)