by Jim Erickson, University of Michigan

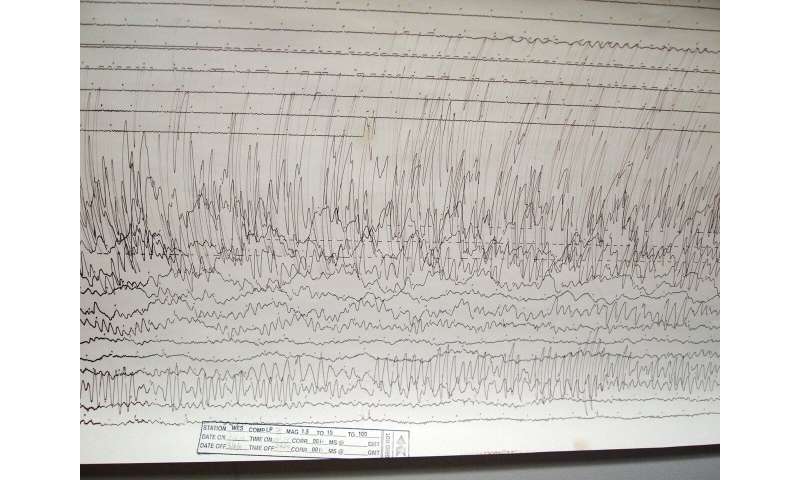

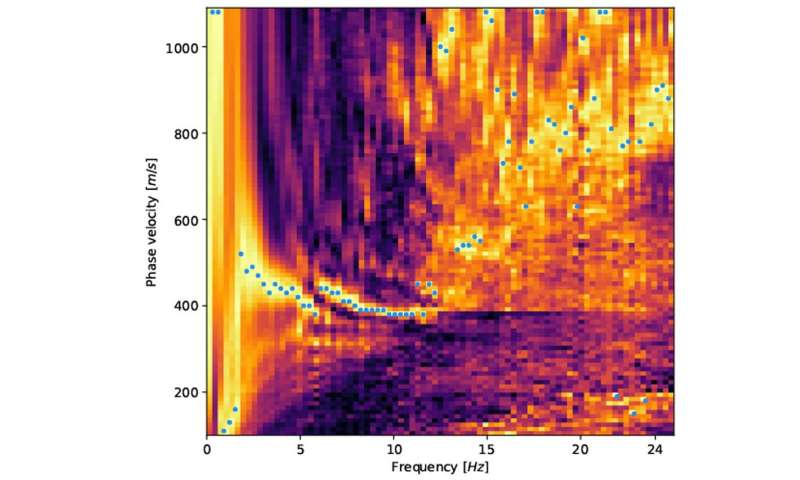

Analysis of seismic wave velocities using distributed acoustic sensing technique with fiber-optic cables. Credit: Zack Spica

A new study from a University of Michigan researcher and colleagues at three institutions demonstrates the potential for using existing networks of buried optical fibers as an inexpensive observatory for monitoring and studying earthquakes.

A new study from a University of Michigan researcher and colleagues at three institutions demonstrates the potential for using existing networks of buried optical fibers as an inexpensive observatory for monitoring and studying earthquakes.

The study provides new evidence that the same optical fibers that deliver high-speed internet and HD video to our homes could one day double as seismic sensors.

"Fiber-optic cables are the backbone of modern telecommunications, and we have demonstrated that we can turn existing networks into extensive seismic arrays to assess ground motions during earthquakes," said U-M seismologist Zack Spica, first author of a paper published online Feb. 12 in the journal JGR Solid Earth.

The study was conducted using a prototype array at Stanford University, where Spica was a postdoctoral fellow for several years before recently joining the U-M faculty as an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. Co-authors include researchers at Stanford and from Mexico and Virginia.

"This is the first time that fiber-optic seismology has been used to derive a standard measure of subsurface properties that is used by earthquake engineers to anticipate the severity of shaking," said geophysicist Greg Beroza, a co-author on the paper and the Wayne Loel Professor in Stanford's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.

To transform a fiber-optic cable into a seismic sensor, the researchers connect an instrument called a laser interrogator to one end of the cable. It shoots pulses of laser light down the fiber. The light bounces back when it encounters impurities along the fiber, creating a "backscatter signal" that is analyzed by a device called an interferometer.

Changes in the backscatter signal can reveal how the fiber stretches or compresses in response to passing disturbances, including seismic waves from earthquakes. The technique is called distributed acoustic sensing, or DAS, and has been used for years to monitor the health of pipelines and wells in the oil and gas industry.

The new study in JGR Solid Earth extends previous work with the 3-mile Stanford test loop by producing high-resolution maps of the shallow subsurface, which scientists can use to see which areas will undergo the strongest shaking in future earthquakes, Beroza said.

In addition, the study demonstrates that optical fibers can be used to sense seismic waves and obtain velocity models and resonance frequencies of the ground—two parameters that are essential for ground-motion prediction and seismic-hazard assessment. Spica and his colleagues say their results are in good agreement with an independent survey that used traditional techniques, thereby validating the methodology of fiber-optic seismology.

This approach appears to have great potential for use in large, earthquake-threatened cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, Tokyo and Mexico City, where thousands of miles of optical cables are buried beneath the surface.

"What's great about using fiber for this is that cities already have it as part of their infrastructure, so all we have to do is tap into it," Beroza said.

Many of these urban centers are built atop soft sediments that amplify and extend earthquake shaking. The near-surface geology can vary considerably from neighborhood to neighborhood, highlighting the need for detailed, site-specific information.

Yet getting that kind of information can be a challenge with traditional techniques, which involve the deployment of large seismometer arrays—thousands of such instruments in the Los Angeles area, for example.

"In urban areas, it is very difficult to find a place to install seismic stations because asphalt is everywhere," Spica said. "In addition, many of these lands are private and not accessible, and you cannot always leave a seismic station standing alone because of the risk of theft.

"Fiber optics could someday mark the end of such large scale and expensive experiments. The cables are buried under the asphalt and crisscross the entire city, with none of the disadvantages of surface seismic stations."

The technique would likely be fairly inexpensive, as well, Spica said. Typically, commercial fiber-optic cables contain unused fibers that can be leased for other purposes, including seismology.

For the moment, traditional seismometers provide better performance than prototype systems that use fiber-optic sensing. Also, seismometers sense ground movements in three directions, while optical fibers only sense along the direction of the fiber.

The 3-mile Stanford fiber-optic array and data acquisition were made possible by a collective effort from Stanford IT services, Stanford Geophysics, and OptaSense Ltd. Financial support was provided by the Stanford Exploration Project, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Schlumberger Fellowship.

The next phase of the project involves a much larger test array. A 27-mile loop was formed recently by linking optical fibers on Stanford's historic campus with fibers at several other nearby locations.

The other authors of the JGR Solid Earth paper are Biondo Biondi of Stanford, Mathieu Perton of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Eileen Martin of Virginia Tech.

Explore furtherResearchers build a 'billion sensors' earthquake observatory with optical fibers

"Fiber-optic cables are the backbone of modern telecommunications, and we have demonstrated that we can turn existing networks into extensive seismic arrays to assess ground motions during earthquakes," said U-M seismologist Zack Spica, first author of a paper published online Feb. 12 in the journal JGR Solid Earth.

The study was conducted using a prototype array at Stanford University, where Spica was a postdoctoral fellow for several years before recently joining the U-M faculty as an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. Co-authors include researchers at Stanford and from Mexico and Virginia.

"This is the first time that fiber-optic seismology has been used to derive a standard measure of subsurface properties that is used by earthquake engineers to anticipate the severity of shaking," said geophysicist Greg Beroza, a co-author on the paper and the Wayne Loel Professor in Stanford's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.

To transform a fiber-optic cable into a seismic sensor, the researchers connect an instrument called a laser interrogator to one end of the cable. It shoots pulses of laser light down the fiber. The light bounces back when it encounters impurities along the fiber, creating a "backscatter signal" that is analyzed by a device called an interferometer.

Changes in the backscatter signal can reveal how the fiber stretches or compresses in response to passing disturbances, including seismic waves from earthquakes. The technique is called distributed acoustic sensing, or DAS, and has been used for years to monitor the health of pipelines and wells in the oil and gas industry.

The new study in JGR Solid Earth extends previous work with the 3-mile Stanford test loop by producing high-resolution maps of the shallow subsurface, which scientists can use to see which areas will undergo the strongest shaking in future earthquakes, Beroza said.

In addition, the study demonstrates that optical fibers can be used to sense seismic waves and obtain velocity models and resonance frequencies of the ground—two parameters that are essential for ground-motion prediction and seismic-hazard assessment. Spica and his colleagues say their results are in good agreement with an independent survey that used traditional techniques, thereby validating the methodology of fiber-optic seismology.

This approach appears to have great potential for use in large, earthquake-threatened cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, Tokyo and Mexico City, where thousands of miles of optical cables are buried beneath the surface.

"What's great about using fiber for this is that cities already have it as part of their infrastructure, so all we have to do is tap into it," Beroza said.

Many of these urban centers are built atop soft sediments that amplify and extend earthquake shaking. The near-surface geology can vary considerably from neighborhood to neighborhood, highlighting the need for detailed, site-specific information.

Yet getting that kind of information can be a challenge with traditional techniques, which involve the deployment of large seismometer arrays—thousands of such instruments in the Los Angeles area, for example.

"In urban areas, it is very difficult to find a place to install seismic stations because asphalt is everywhere," Spica said. "In addition, many of these lands are private and not accessible, and you cannot always leave a seismic station standing alone because of the risk of theft.

"Fiber optics could someday mark the end of such large scale and expensive experiments. The cables are buried under the asphalt and crisscross the entire city, with none of the disadvantages of surface seismic stations."

The technique would likely be fairly inexpensive, as well, Spica said. Typically, commercial fiber-optic cables contain unused fibers that can be leased for other purposes, including seismology.

For the moment, traditional seismometers provide better performance than prototype systems that use fiber-optic sensing. Also, seismometers sense ground movements in three directions, while optical fibers only sense along the direction of the fiber.

The 3-mile Stanford fiber-optic array and data acquisition were made possible by a collective effort from Stanford IT services, Stanford Geophysics, and OptaSense Ltd. Financial support was provided by the Stanford Exploration Project, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Schlumberger Fellowship.

The next phase of the project involves a much larger test array. A 27-mile loop was formed recently by linking optical fibers on Stanford's historic campus with fibers at several other nearby locations.

The other authors of the JGR Solid Earth paper are Biondo Biondi of Stanford, Mathieu Perton of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Eileen Martin of Virginia Tech.

Explore furtherResearchers build a 'billion sensors' earthquake observatory with optical fibers

More information: Zack J. Spica et al, Urban Seismic Site Characterization by Fiber‐Optic Seismology, Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth (2020). DOI: 10.1029/2019JB018656