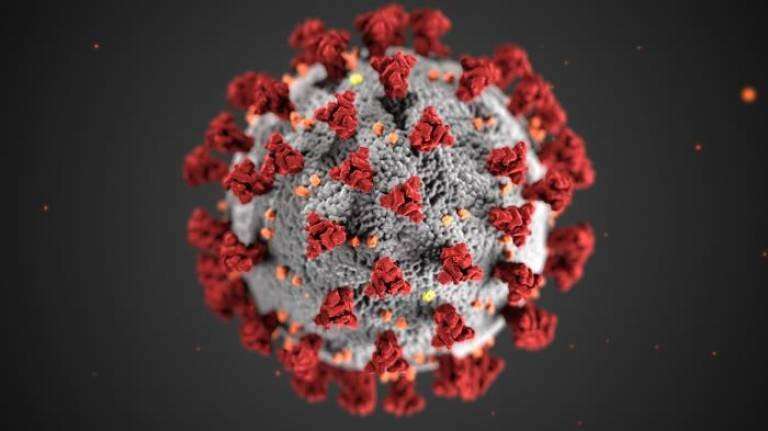

Research: Lockdowns need to last more than six weeks to contain COVID-19

People around the world are wondering how long COVID-restrictions have to last in order to curtail the pandemic.

A research study on 36 countries and 50 U.S. states has found that aggressive intervention to contain COVID-19 must be maintained for at least 44 days. The study is co-authored by Professor Gerard Tellis of USC Marshall School of Business, Professor Ashish Sood of UC Riverside's A. Gary Anderson Graduate School of Management, and Nitish Sood, a student at Augusta University studying Cellular & Molecular Biology. The paper is published in the open sources journal SSRN and is titled, "How Long Must Social Distancing Last."

MARCH 27/2020 MODELING HOW NOT TO PRACTICE

PANDEMIC SOCIAL DISTANCING

HEALTH CARE WORKERS PROTEST ON THEIR NEED FOR PPE AND SAFE WORKING CONDITIONS PRACTICING SAFE DISTANCING ON THE PICKET LINE

The authors identify two simple, intuitive, and generalizable metrics of the spread of disease: daily growth rate and time to double cumulative cases. Daily growth rate is the percentage increase in cumulative cases. Time to double, or doubling time, is the number of days for cumulative cases to double at the current growth rate. Time to double in disease spread is the opposite of half-life in drug metabolism.

"Counts of total or new cases can be misleading and difficult to compare across countries," Professor Tellis said. "Growth rate and Time to double are critical metrics for an accurate understanding of how this disease is spreading."

Given these two metrics, the researchers defined three measurable benchmarks for analysts and public health managers to target:

- Moderation: when growth rate stays below 10% and doubling time stays above seven days.

- Control: when growth rate stays below 1% and doubling time stays above 70 days.

- Containment: when growth rate remains 0.1% and doubling time stays above 700 days.

"These simple, intuitive, and universal benchmarks give public health officials clear goals to target in managing this pandemic," Professor Sood said.

Preliminary results using this model to analyze the data suggest that once aggressive interventions are in place, large countries take almost three weeks to see moderation, one month to get control, and 45 days to achieve containment. With less aggressive intervention, it can take much longer. Important differences exist by size of country. Public health administrators should note larger countries take longer to see moderation.

The authors defined aggressive intervention as lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, mass testing and quarantines.

"Singapore and South Korea adopted the path of massive test and quarantine, which seems to be the only successful alternative to costly lockdowns and stay-at-home orders," Nitish Sood said.

Their research focuses on diffusion of innovations, new products, and new technologies. The same concepts and tools can be applied to analyze the spread of COVID-19 and the effects of measures to stop it.

"Even though huge differences exist among countries, it's striking to see so many similarities from aggressive intervention to moderation, control, and containment of the spread of the disease," Professor Sood said.

Professor Tellis added, "Besides size of country, borders, cultural greetings (bowing versus handshaking and kissing), temperature, humidity, and latitude may explain these differences."

The researchers say their analysis bolsters the case for adopting aggressive measures, whether it's the aggressive lockdowns of Italy or California, massive testing and quarantine of South Korea or Singapore, or a combination of both as seen in China. However, the U.S. may have a unique challenge because of its federal constitution.

Only half of the states have adopted aggressive intervention and that at varying times. Should these states achieve control or containment, they may be vulnerable to contagion from states that were late to do so, the researchers say.Lack of testing doesn't explain why Japan has so far escaped the worst of the coronavirus

More information: Gerard J. Tellis et al. How Long Should Social Distancing Last? Predicting Time to Moderation, Control, and Containment of COVID-19, SSRN Electronic Journal (2020). DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.356299