Anterior insula activation restores prosocial behavior in animal model of opioid addiction

A new study in animals suggests that the social and interpersonal problems associated with opioid addiction might be reversible.

Researchers in the Arizona State University Department of Psychology previously used an animal model of opioid addiction and empathy to show that animals stopped prosocial behaviors—helping another animal—when heroin was available. The same research group has now shown that activating the anterior insula restored prosocial behaviors in opioid-addicted animals. The study will be published in Social Neuroscience and is now available online.

Researchers in the Arizona State University Department of Psychology previously used an animal model of opioid addiction and empathy to show that animals stopped prosocial behaviors—helping another animal—when heroin was available. The same research group has now shown that activating the anterior insula restored prosocial behaviors in opioid-addicted animals. The study will be published in Social Neuroscience and is now available online.

"As a master's student, I led support groups for opioid addicts, and the biggest problems people wanted help dealing with were social. Our finding in an animal model of opioid addiction that chemogenetic activation of the anterior insula restores prosocial behavior suggests a glimmer of hope that some of the social behavioral deficits in opioid addiction are not permanent," said Seven Tomek, who just defended her doctoral dissertation at ASU. Tomek is first author on the paper and received training in substance abuse treatment while earning her master's in clinical psychology from the University of North Carolina, Wilmington.

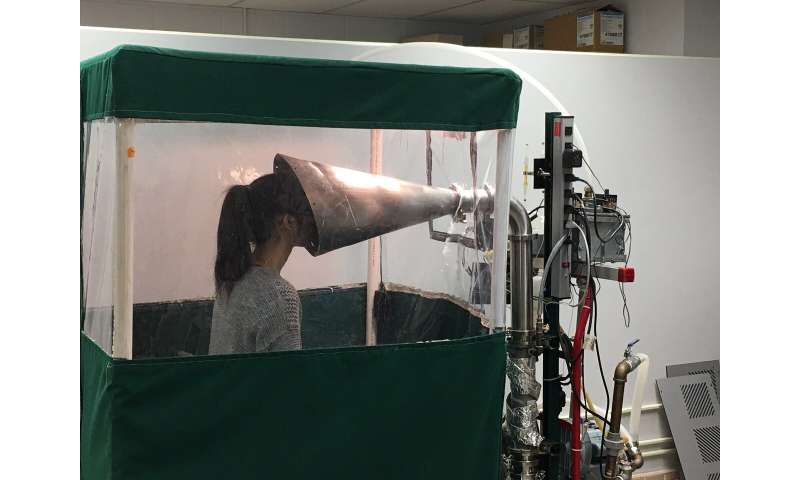

To measure prosocial behavior, the researchers trained animals to free another animal that was trapped in a clear plastic tube. The animals had access to heroin for two weeks and then were given the choice of consuming heroin or helping another animal. Like before, the animals again chose heroin over helping another.

To try and restore the prosocial behaviors in the animals, the research team targeted a brain region involved in both prosocial behaviors like helping and addictive behaviors like craving: the anterior insula.

"We designed our animal study based on work in people showing that damage in the anterior insula area—from a stroke for example—was correlated with easily quitting cigarette smoking," Tomek said. "This brain area is also important for motivation and emotions in people."

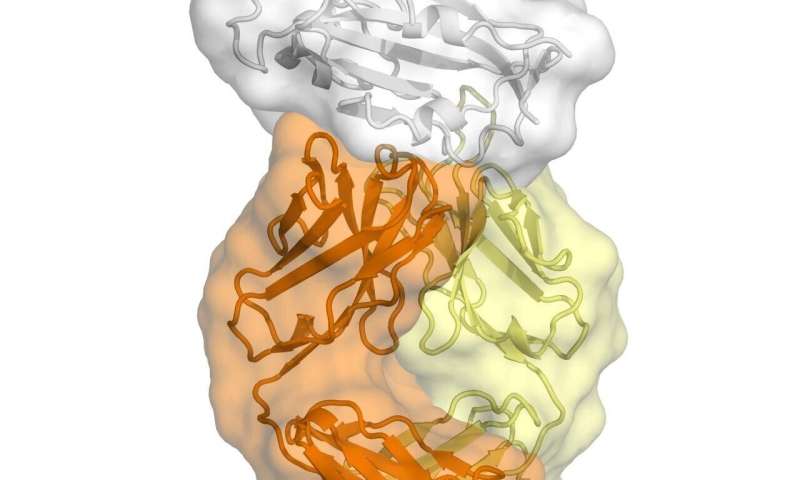

The insula is nicknamed the "hidden lobe" because it is tucked underneath the brain's frontal, parietal and temporal lobes. This location makes access difficult, so the research team used chemogenetic methods—called Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs, or DREADDs for short—to selectively activate the anterior insula in the animals. Using DREADDs is like installing a smart lock on specific neurons, and then only granting access the lock when scientists want to activate the neurons. The DREADD method inserts mutant receptors into neurons, and those receptors can only be activated by a chemical that is not naturally present in the body.

"Once we activated the excitatory DREADD in the anterior insula, the animals started rescuing the trapped animals again," Tomek said.

The research team tested the role of anterior insula activation twice. In the first experiment, the animals who underwent DREADD activation helped other animals 67% of the time when heroin was available. The control group only helped other animals 17% of the time. In the second experiment, activation of the anterior insula was again associated with helping other animals 67% of the time. The second control group helped other animals 44% of the time.

"This work demonstrates an important role for the anterior insula in opioid addiction and shows the possibilities of changing a social behavior that has been compromised by drug use," said Foster Olive, professor of psychology at ASU and senior author on the paper.

More information: Seven E. Tomek et al, Restoration of prosocial behavior in rats after heroin self-administration via chemogenetic activation of the anterior insular cortex, Social Neuroscience (2020). DOI: 10.1080/17470919.2020.1746394

Provided by Arizona State