What Is Cryptozoology and How Do You Become a Cryptozoologist?

Luther Urswick

Updated on June 17, 2019

Luther Urswick

Updated on June 17, 2019

With interests in science, nature, history and the paranormal, Luther explores topics from a unique and sometimes controversial perspective.

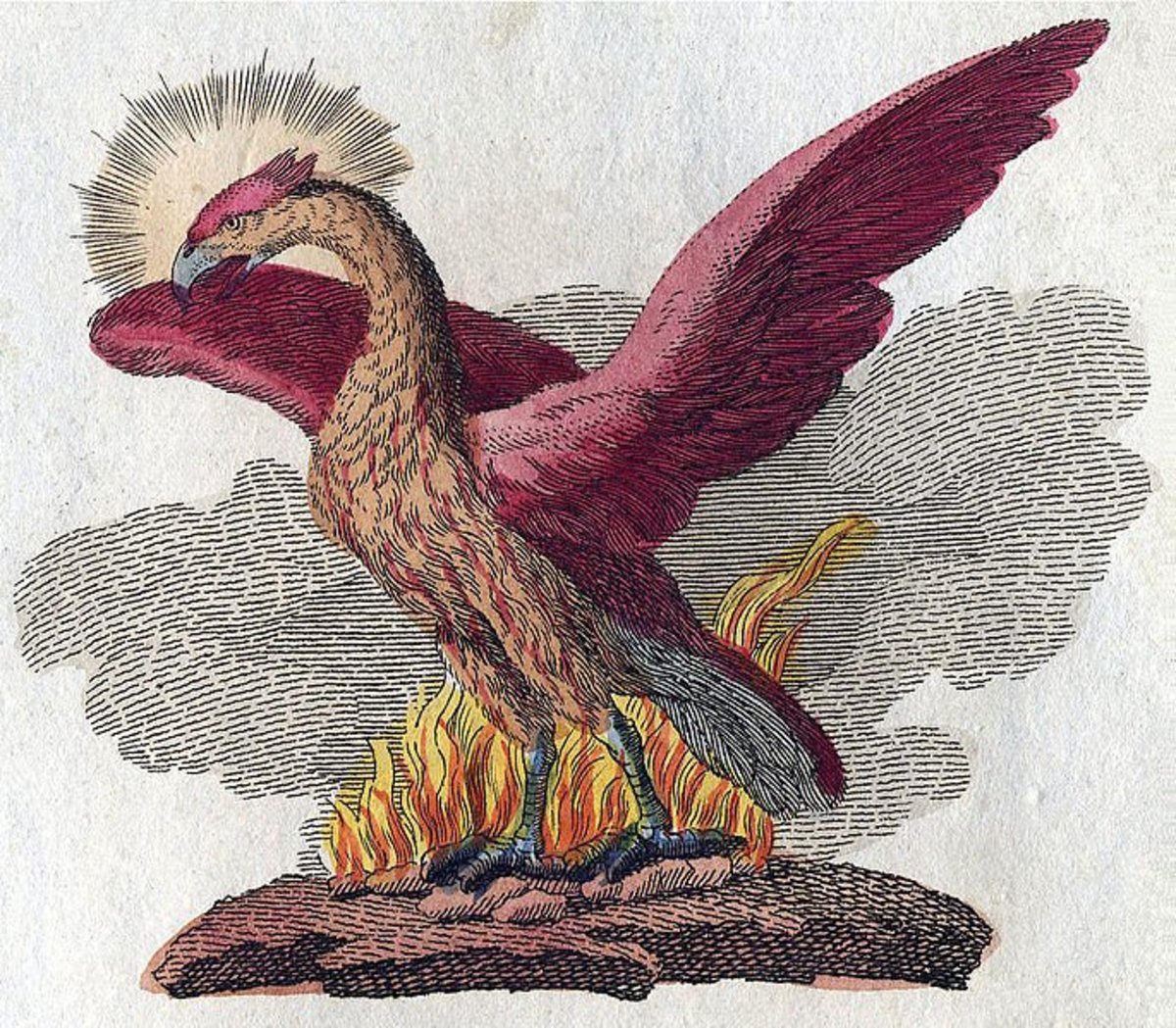

Legends of strange creatures have been with us since the beginning of time. Cryptozoologists study these animals, and sort of out fact from fiction. | Source

Legends of strange creatures have been with us since the beginning of time. Cryptozoologists study these animals, and sort of out fact from fiction. | Source

What Is Cryptozoology?

The word cryptozoology means literally the "study of hidden animals”, those which some people believe are out there but science has yet to officially acknowledge.

Think of Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster. You know, those creatures that make your friends smile, nod and slowly move away from you whenever you bring them up in conversation. These mystery creatures (the animals, not your friends) are known as cryptids.

Cryptozoology has unfortunately earned a reputation with the mainstream public as a kooky diversion, practiced by the same guys who contact UFOs using modified CB radios while wearing hats made from tin foil. However, the good cryptozoologists are more about science than silliness, and have hatched some compelling theories over the years to explain sightings of unusual animals.

But even the best cryptozoologists have a lot working against them. A serious biologist or zoologist who spends their time and money in the pursuit of some mythical creature is risking career suicide. There is little grant money to be had for a researcher who decides to take a year away from teaching at the University and treks off to the Himalayas in hopes of meeting a Yeti.

Along with financial struggles and losing the respect of your mainstream peers comes the frustration of limited results for your efforts. Progress moves slowly in cryptozoology, and new discoveries and evidence are hard to come by. A researcher may spend a lifetime searching in vain.

So why do they do it? What makes these people tick? And do they ever really come up with any evidence aside from footprints and blurry pictures?

What Do Cryptozoologists Study?

If cryptozoology is the study of unknown animals than one could argue that by going into your backyard and turning up rocks in the hopes of finding some undiscovered bug you are indeed a cryptozoologist. You’re searching for unknown animals, and it’s a lot less expensive and time consuming than a month-long trip to Africa.

In fact, there are likely thousands if not millions of undiscovered insect species in the world, most of them in deep jungles. So why aren’t more cryptozoologists creeping around in the rainforest with a magnifying glass?

It’s not so simple. There is no debate that there are countless undiscovered animals in the world. However, there is a great deal of debate regarding the remaining species of large fauna yet to be discovered.

Cryptozoology is about finding the big animals, those creatures that many of us believe can’t possibly have gone undiscovered for so long. Some are so bizarre that there must be a supernatural component to their existence. Some are believed to be real animals, yet to be discovered by science.

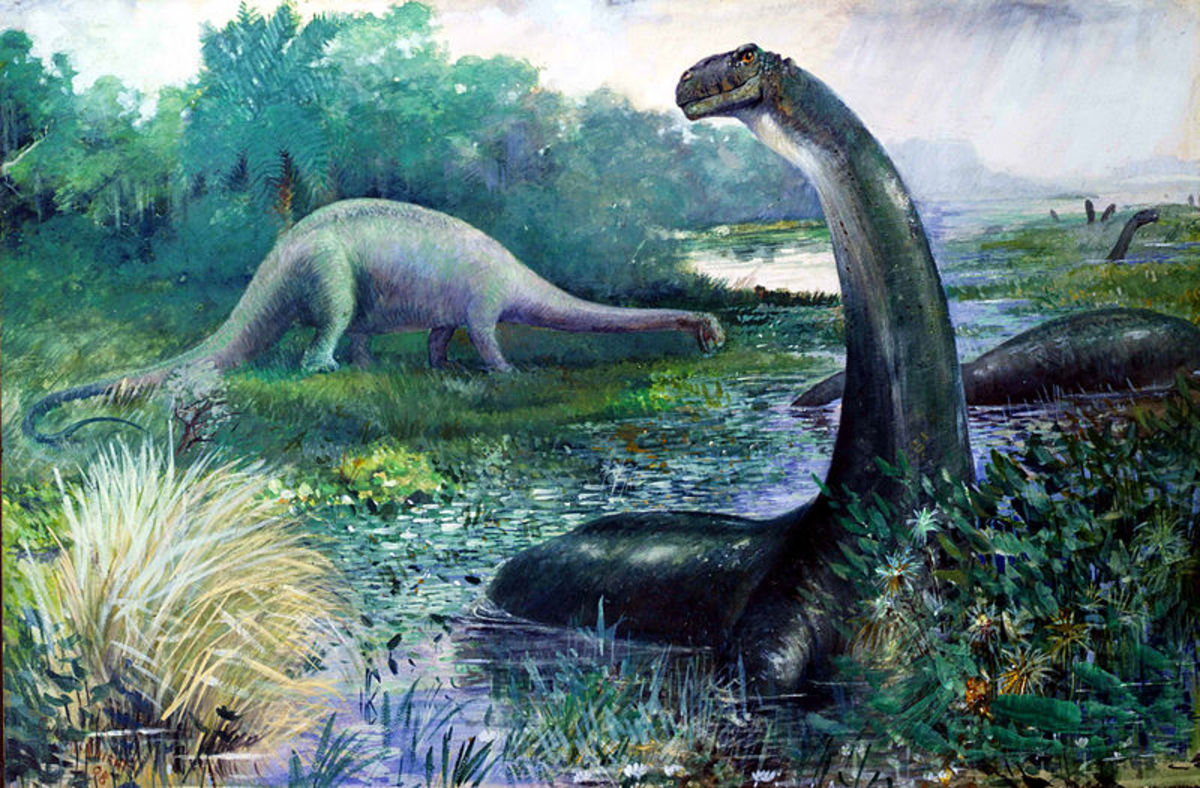

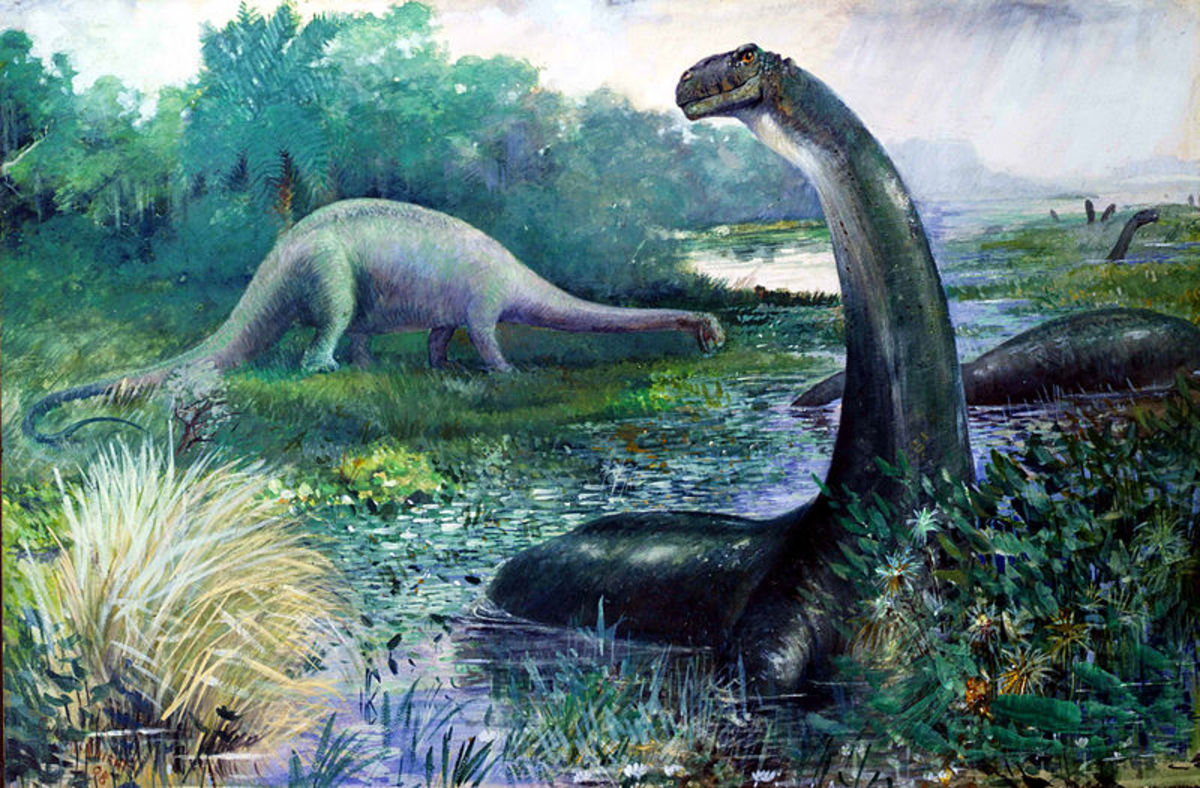

Others are creatures that we know once roamed the Earth, but science tells us they went extinct long ago. Some say there are fascinating prehistoric beasts still lurking in far corners of the world, even living dinosaurs.

This is the part that separates cryptozoology from mainstream science. Logically, it makes little sense for many of these creatures to have eluded human detection, and we often dismiss the idea of their existence as borderline absurd.

Still, many of us are intrigued. Wouldn’t it be interesting if some of these fantastic tales of bizarre animals proved to be true? And that’s what makes a cryptozoologist get out of bed in the morning. We’re all interested in the possibility of the unknown, but they get out there and look for it.

How to Become a Cryptozoologist

If you’re considering a career in cryptozoology it’s probably a good idea to take a step back and think things through. While there are a handful of researchers who make a living writing books, lecturing and even hosting TV shows or radio programs, for most cryptozoologists it is a labor of love.

That’s an artistic way of saying you probably aren’t going to make much money doing it. In fact, you’ll spend a lot of money in the process. That doesn't mean cryptozoology isn’t a worthwhile pursuit, but you do need to be realistic about it.

There are no real qualifications to becoming a cryptozoologist, no degree programs and no governing body. You simply need to have an interest, and get out and do it. However, it is important to note that earning the respect of your peers (other serious researchers) will serve as a kind of credentialing process.

There are all kinds of monster hunters out there, and those who give cryptozoology a bad name are no help to the emerging science.

If you believe you want to pursue cryptozoology in your spare time, or even see if you can somehow make a career out of it, it’s a good idea to look at comparable mainstream sciences as your main area of study.

You may go to school and earn a degree in anthropology, zoology, marine biology or some other natural science, with the eventual goal of become a professor. Teachers get lots of time off, and at least you’d have a glimmer of hope for snagging some grant money for your studies.

Or you may wish to pursue another totally unrelated field. Cryptozoolgists come from every profession, and have taken many diverse paths. You may wish to choose something where you can make tons of money to fund your yearly expeditions in search of the Megalodon shark!

What Would You Do?

You're looking out your kitchen window into your backyard one morning and you spot Bigfoot! You get a clear view, and you're sure it is him. You even snap a couple of pictures. What do you do next?

Find a buyer for the pictures and cash in. Cha ching!

Get on the phone and tell everyone I know. This is so cool!

Tell only a few people I can trust to keep a secret.

Tell nobody and keep the pictures safe. It's a private experience between me and nature.

Check myself into the hospital. Hopefully this delusion was just caused by something I ate.See results

Where It All Began

No doubt humans have been telling tall tales about strange animals since the invention of language, but what we think of as modern cryptozoology is likely only a bit older than a century. In 1892 a Dutch zoologist named Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans published the manuscript called The Great Sea Serpent.

Here, Oudemans contends that sighting of sea serpents may be attributed to an as-yet-unknown species of giant, elongated seal. Oudemans was a respected scientist, the director of the Dutch Royal Zoological Gardens, but few took his book seriously. And they still haven’t found the giant seal.

Explorer and researcher Bernard Heuvelmans is another notable figure in early cryptozoology. In 1955 Heuvelmans published On theTrack of Unknown Animals, a book that earned him the title of Father of Cryptozoology . Heuvelmans’s book laid out a detailed account of cryptids from around the world, and inspired many a young mind to take up their pursuit.

Nowadays, you can hardly click on the television without coming across a show on cryptozoology. Finding Bigfoot, which airs on Animal Planet, is perhaps the most noteworthy. Destination Truth (Syfy Channel), and Beast Hunter (National Geographic Channel) are other shows which have delved heavily into the search for unknown creatures.

So if all these people are out there looking why don’t we have crystal-clear photos of a smiling Sasquatch with his arm around a researcher by now? What exactly are these people looking for, and what are the chances of finding it?

Oudemans's search for the legendary sea serpent led him to suggest sightings were due to a strange, rare seal. | Source

Oudemans's search for the legendary sea serpent led him to suggest sightings were due to a strange, rare seal. | Source

Strange and Elusive Creatures

Below you'll read about a few of the more famous creatures in the world of cryptozoology. None of these animals have been proven my mainstream science, but nevertheless there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest they are out there. As a cryptozoologist you may specialize in the study of one or more of these creatures.

Bigfoot

He’s the star of the cryptozoology world, known to deftly elude researchers but then reveal himself to anyone with a camera incapable of shooting a clear picture.

Called Sasquatch in the Pacific Northwest, Skunk Ape in the South and Yeti in the Himalayas, Bigfoot is believed to be a species of undiscovered ape, possibly evolved from the extinct Gigantopithecus Blacki.

Sightings date back to Native American times, and in modern days Bigfoot is spotted in just about every inch of the United States and Canada, so it seems your chances of spotting him are better than they are for most creatures on this list.

Amazing Evidence from the Show "Finding Bigfoot"

Loch Ness Monster

Second only to the big, hairy guy listed above, Nessie is said to inhabit Loch Ness of Scotland.

It’s a huge lake and extremely deep. The lake is connected to the ocean by waterways, leading some to believe Nessie could be a sea creature of some kind, or at least travel that route to and from the ocean.

Furthering that theory is the debate of whether or not Loch Ness contains the food necessary to support a population of such large creatures. Like other lake monsters such as Ogo Pogo and Champ, Nessie is thought by some to be a Plesiosaur, a species of aquatic reptile long gone extinct.

Orang Pendek

Translated to “Short Person” in Indonesian, Orang Pendek is a small, hairy, bipedal humanoid creature spotted in the jungles of Sumatra.

Like a tiny Bigfoot, Orang Pendek may be an undiscovered species of ape or other primitive hominid. But it may also share a much closer relation to humans.

The discovery of the bones of a species of small, prehistoric human dubbed Homo floresiensis on the Indonesian island of Flores sparked the theory that Orang Pendek may be a related species, hidden in the jungles and rarely seen.

Mapinguari

It’s a giant beast that terrorizes locals in the South American jungles, with a mouth on its stomach, backward-facing feet, huge claws and a horrible stench.

It might sounds crazy, but some researchers think the Mapinguari may be a species of giant ground sloth thought to have gone extinct thousands of years ago.

Megatherium was a species of massive sloth that some researchers think may have existed as recently as 15,000 years ago. Could it be that this beasty that terrorizes natives in the jungle is actually a living Megatherium? Until somebody finds one, we just don’t know.

Megalodon Shark

Thousands of years ago a massive shark over 50 feet in length stalked the world’s oceans and some say it is still around.

Like a monstrous great white it fed on marine mammals, in this case enormous whales and other large creatures. It was called Carcharodon Megalodon, and it was the apex predator of its day and the largest carnivore ever to exist on this planet.

While modern science says it went extinct thousands of years in the past, some say Meg is still around today, lurking deep in the ocean. Strange creatures once thought extinct have resurfaced before, and we still have a huge percentage of the ocean left to explore. Could Megalodon still be out there?

Mokele Mbembe

Is it possible that there are isolated places in the world where dinosaurs still exist, undocumented by modern science and lost to history?

Mokele Mbembe is a beast known to local tribes in the African Congo. It is described as having the body of an elephant with a long neck and small head. To some brave researchers, this sounds like a sauropod dinosaur.

But Mokele Mbeme isn’t the only dino still plodding around in Africa. Several different types of creatures have been spotted in and around the Congo River basin, leading some researchers to think a small remnant population of dinosaurs may well exist in Africa.

It makes absolutely no sense based on what we know of the history of the planet, but there is no denying that people are spotting strange things in Africa, and they describe them as dinosaurs.

Could some dinosaurs have survived extinction and still live today? | Source

Could some dinosaurs have survived extinction and still live today? | Source

Do You Believe in Strange Creatures?

“Do you believe” is really the wrong question to ask in cryptozoology. Because we’re talking about animals that may be real, belief is irrelevant. Science can and should bear out the existence of these creatures over time, if they exist. Any interest in exploring unknown cryptids should spur from the facts available, not some mystical belief in the wonders of the universe.

Most of these creatures, by way of sightings and other evidence, merit at least some level of scientific investigation. We’ve all heard the old cliché about the remaining unexplored parts of our globe, and what a shame it would be to ignore our curiosity for amazing discoveries. It would be an incredible thing to validate a legend.

Or would it? What if a population of Bigfoot were discovered and documented by mainstream science? True, it would amaze and shock the world, and the name of the researcher who found them would go down in history.

But what next? Do we put them in a zoo? Dissect and analyze them? While we all would like to see the mysteries of the world revealed? Would the final result of such a discovery be worth it? Perhaps some mysteries are better left alone.

No matter what is eventually discovered, it’s hard to imagine that mankind’s of the unknown will ever be satisfied. There will never be a shortage of stories of strange creatures or people willing to go out and look for them. There will always be a place in the world for Cryptozoology .

Is Finding Bigfoot a Good Idea?

What would happen if a population of Sasquatch were discovered?

They'd be tagged, bagged and carted off to some research facility.

On the surface it would seem like a good thing, but they'd be exploited soon enough.

Laws would be passed and they would be protected.

It would be awesome, and we're evolved enough to treat them right.See results

Xi Jinping, Winnie the Pooh and the Canadian origins of the bear that’s banned in ChinaXi Jinping

Comparisons between the beloved character and the Chinese president might have gone viral, but few are aware that Winnie’s story began in Canada during World War I

Patrick Blennerhassett 30 Dec, 2019

While most are now familiar with satirical comparisons of Chinese President Xi Jinping and popular children’s cartoon character Winnie the Pooh, fewer may know that the lovable bear’s origins lead all the way to a heartland Canadian city during the first world war.

Now, for the first time since “ Xi the Pooh” took root in 2013 – leading to Winnie’s likeness being banned in China, whether as a stuffed toy, paper mask or social-media sticker – the author of two books on the bear’s history, and great-granddaughter of Winnie’s original owner, has spoken about the bear’s enduring worldwide popularity (except, you know, in that one place).

“It is so outrageous and absurd,” says Canadian Lindsay Mattick, whose award-winning children’s books are still available in China despite the controversy. “To ban something like Winnie the Pooh, one of the most loving, peaceful and happy stories of all time, is really quite sad.”

Lindsay Mattick, the great-granddaughter of Harry Colebourn,

Winnie’s original owner, and author of the book Finding Winnie.

Photo: Lindsay Mattick

In 1914, a trainload of military men pulled into White River, Ontario, on their way to training in Quebec before heading to the war in Europe. During the brief stop, a 27-year-old Canadian soldier, Harry Colebourn, originally from England, made a purchase from a trapper: a black bear cub.

Lindsay Mattick, the great-granddaughter of Harry Colebourn,

Winnie’s original owner, and author of the book Finding Winnie.

Photo: Lindsay Mattick

In 1914, a trainload of military men pulled into White River, Ontario, on their way to training in Quebec before heading to the war in Europe. During the brief stop, a 27-year-old Canadian soldier, Harry Colebourn, originally from England, made a purchase from a trapper: a black bear cub.

The trapper had killed the mother but said he could not do the same to its cub. Smitten, Colebourn handed over some cash and dubbed the female cub Winnie, after his adopted hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Colebourn took Winnie to England, where she became the regimental mascot of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps before, realising the severity of the fighting, he reluctantly gave her to London Zoo. Winnie went on to become a star attraction, catching the eye of a little boy called Christopher Robin Milne, who renamed his teddy bear Winnie in her honour.

His bear and other toy animals would inspire his father, author A.A. Milne, in 1926 to create Winnie-the-Pooh (“Pooh” was Christopher Robin’s name for a swan), one of the world’s most beloved children’s characters, appearing in four books and, half a century later, in Walt Disney’s world-famous animation.

Mattick discovered her great-grandfather’s connection to the stories as a child, while reading his diary with her family. In 2015 she published the children’s picture book Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear, winner of the Caldecott Medal in 2016. The book tells the story of Winnie and Harry and then Winnie and Christopher Robin. (Her second book, Winnie’s Great War, was published in 2018.)

“She was at the London Zoo for 20 years,” Mattick says. “She had a very friendly, docile nature, which is not the norm for a bear. But I would like to think that she got off on the right foot with my great-grandfather, who really loved animals and cared for her.”

The cartoon version of Winnie the Pooh first appeared in 1977, in Disney’s The Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, about the lovable bear and his animal friends – Piglet, Eeyore, Kanga, Roo, Rabbit and Tigger.

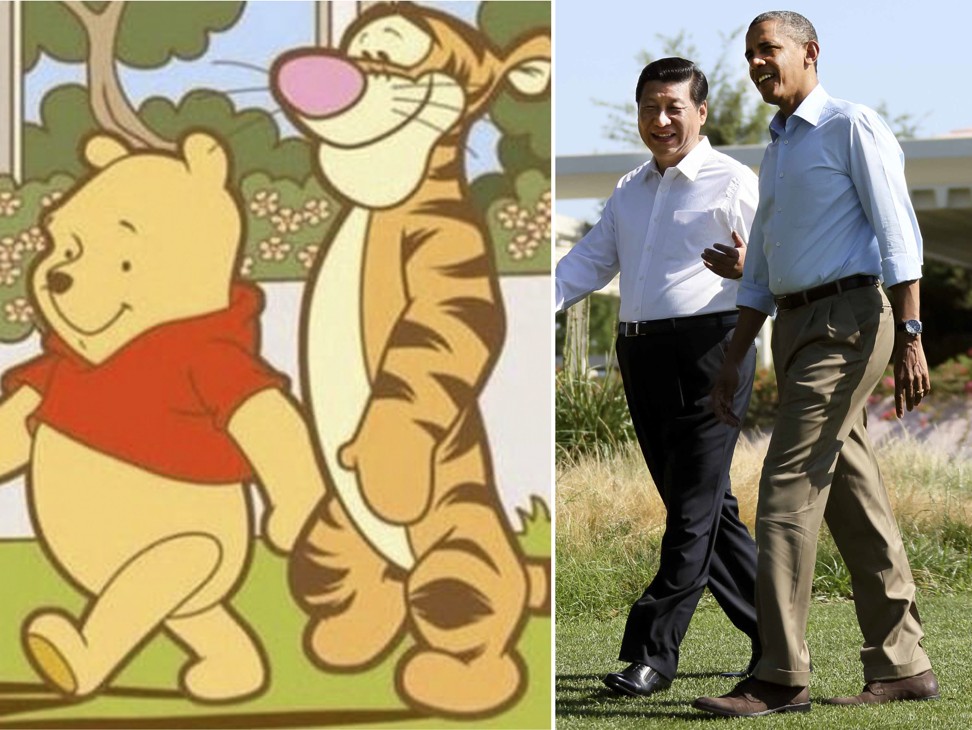

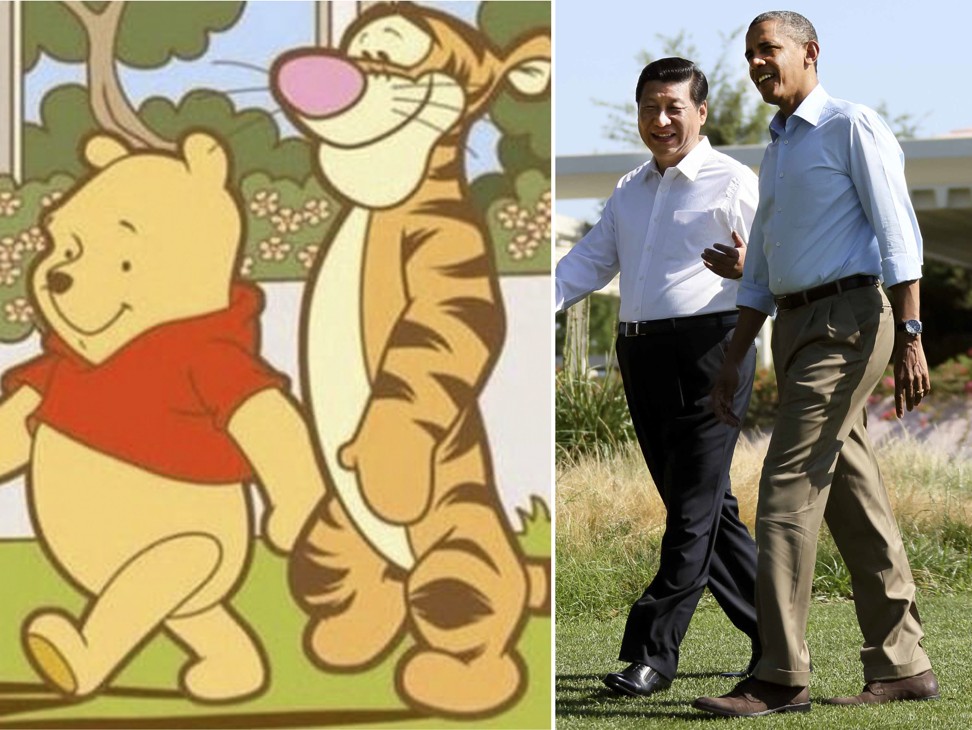

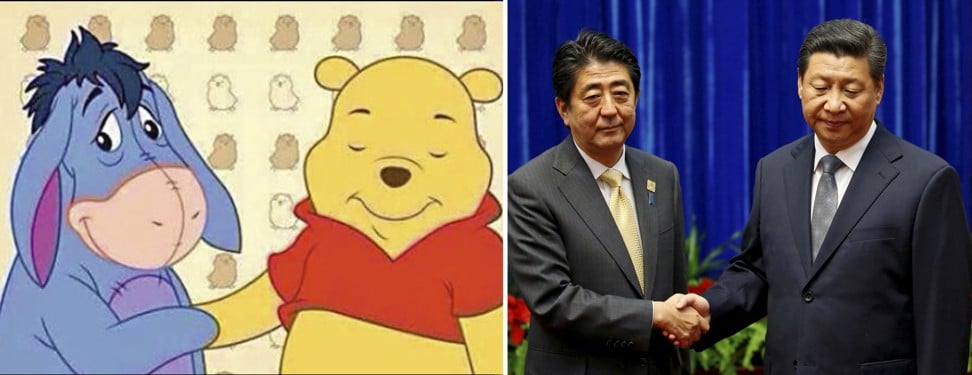

For the next few decades, Winnie the Pooh and his cohort were universally beloved. Then in 2013, Mattick, who runs her own public relations company in Toronto, caught wind of a bizarre case of anti-Winnie-ism. A photo had surfaced online of Xi and United States president Barack Obama next to a picture of similarly positioned cartoon characters, likening Obama to Tigger and Xi to Winnie the Pooh.

The Reuters image of Chinese President Xi Jinping with then US President Barack Obama next to a picture of Winnie the Pooh and Tigger that went viral on Weibo in 2013. Photo: Xinhua

The Reuters photo of the two leaders was taken during a summit in Sunnylands, California, but the source of the split shot is unknown. It soon went viral on Weibo, China’s ersatz answer to Twitter. Pictures were quickly deleted by censors, who apparently did not appreciate the comparison of the Chinese president to a bashful, hapless, chubby yellow bear.

When Mattick heard the news, she had a tough time wrapping her head around it. She did not do any media interviews, but she did receive a lot of messages from friends and family about the rather odd news that the leader of a country could be so thin-skinned as to think Winnie the Pooh posed a threat.

The Reuters image of Chinese President Xi Jinping with then US President Barack Obama next to a picture of Winnie the Pooh and Tigger that went viral on Weibo in 2013. Photo: Xinhua

The Reuters photo of the two leaders was taken during a summit in Sunnylands, California, but the source of the split shot is unknown. It soon went viral on Weibo, China’s ersatz answer to Twitter. Pictures were quickly deleted by censors, who apparently did not appreciate the comparison of the Chinese president to a bashful, hapless, chubby yellow bear.

When Mattick heard the news, she had a tough time wrapping her head around it. She did not do any media interviews, but she did receive a lot of messages from friends and family about the rather odd news that the leader of a country could be so thin-skinned as to think Winnie the Pooh posed a threat.

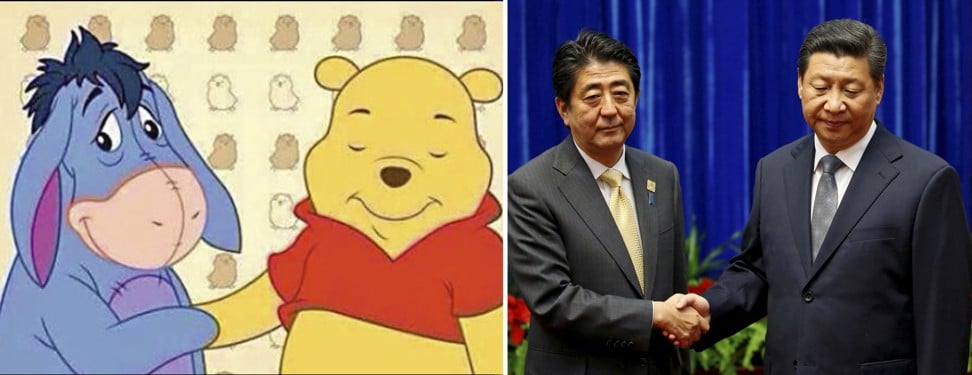

China’s Winnie the Pooh ban has since extended to the release ofChristopher Robin , a 2018 film starring Ewan McGregor as the boy who fell in love with Winnie. While censoring the image in China is one aspect of the story, it has given the meme a life outside the mainland. Internet users continue to link images of Xi to Winnie the Pooh, including one in 2014 with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe filling in as Pooh’s melancholy donkey pal, Eeyore.

Of course, this is not the only thing the Chinese government has deemed unsuitable for its citizens. A long list of entertainment-related images, books, memes and shows have been banned over the years, the latest being the satirical US cartoon South Park, after a recent episode took a dig at China.

The image of Eeyore and Winnie the Pooh that proliferated after comparisons were drawn between Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Xi and the two cartoon characters. Photo: Reuters

Vancouver-based University of British Columbia professor Florian Gassner, who specialises in the role of censorship in society, says Beijing’s actions have had both intended and unintended consequences. He says it is important to remember the target of this ban is internal, not external.

“And we should probably not forget that a lot of citizens in China support the Communist Party,” Gassner says. “When they see their government strike something down like this, it could be interpreted as the system working.”

It’s a trend Gassner has been seeing in authoritative countries where censorship has been taken to a new level, from India’s online troll armies to Russia’s state media. “The part that fascinates me is that governments are not capitulating, they are doubling down, doing their best to get all of this under control,” he says.

Mattick, who has held exhibitions about Winnie’s origins, says she hopes families in China can still enjoy the stories the bear has inspired, given their positive messages.

“I hope the Chinese population has the chance to not only read about the story but feel good about the story and feel proud about sharing it with their children without feeling like they are doing something subversive,” she says. “I feel sad that this particular chain of events has led to such a mixed perception that doesn’t seem in any way keeping with the spirit of the books and the stories.”

The image of Eeyore and Winnie the Pooh that proliferated after comparisons were drawn between Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Xi and the two cartoon characters. Photo: Reuters

Vancouver-based University of British Columbia professor Florian Gassner, who specialises in the role of censorship in society, says Beijing’s actions have had both intended and unintended consequences. He says it is important to remember the target of this ban is internal, not external.

“And we should probably not forget that a lot of citizens in China support the Communist Party,” Gassner says. “When they see their government strike something down like this, it could be interpreted as the system working.”

It’s a trend Gassner has been seeing in authoritative countries where censorship has been taken to a new level, from India’s online troll armies to Russia’s state media. “The part that fascinates me is that governments are not capitulating, they are doubling down, doing their best to get all of this under control,” he says.

Mattick, who has held exhibitions about Winnie’s origins, says she hopes families in China can still enjoy the stories the bear has inspired, given their positive messages.

“I hope the Chinese population has the chance to not only read about the story but feel good about the story and feel proud about sharing it with their children without feeling like they are doing something subversive,” she says. “I feel sad that this particular chain of events has led to such a mixed perception that doesn’t seem in any way keeping with the spirit of the books and the stories.”

Patrick Blennerhassett is an award-winning Canadian journalist and four-time published author. He is a Jack Webster Fellowship winner and a British Columbia bestselling novelist. His work has been published in The Guardian, Reader's Digest, The Globe & Mail, Business Insider, MSN and his commentary has appeared on the BBC and the CBC.

Patrick Blennerhassett is an award-winning Canadian journalist and four-time published author. He is a Jack Webster Fellowship winner and a British Columbia bestselling novelist. His work has been published in The Guardian, Reader's Digest, The Globe & Mail, Business Insider, MSN and his commentary has appeared on the BBC and the CBC.

FROM THE SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST SCMP

These 11 Maps Show How Black People Have Been Driven Out Of Neighborhoods In Five Of The Most Gentrified US Cities

The maps distinctly show neighborhoods where black populations have left and where white people have moved in.

Lam Thuy Vo BuzzFeed News Reporter Posted on February 27, 2020

Kate Wolffe / AP

Moms 4 Housing activists stand outside a vacant home on Magnolia Street in West Oakland that they occupied, saying they were unable to find permanent housing in the Bay Area, in December 2019.

We have known for years that gentrification has disproportionately displaced black and Latino people from their homes across the US, “excluding existing residents from the benefits of a revitalizing neighborhood,” as one study put it. The statistics prove it, we make cultural statements about it, and there’s rising activism around it.

Kate Wolffe / AP

Moms 4 Housing activists stand outside a vacant home on Magnolia Street in West Oakland that they occupied, saying they were unable to find permanent housing in the Bay Area, in December 2019.

We have known for years that gentrification has disproportionately displaced black and Latino people from their homes across the US, “excluding existing residents from the benefits of a revitalizing neighborhood,” as one study put it. The statistics prove it, we make cultural statements about it, and there’s rising activism around it.

To help visualize how minority communities are pushed out by white populations, BuzzFeed News ran an analysis of five of the most gentrified US cities. The results show how the demographics changed between 2000 and 2017 and highlight which census tracts have gentrified in that time.

Here’s how you can read each map: the city is split up into census tracts — a geographic region of a few thousand people. For each major race group in the census, the tracts are shaded according to how that group's representation changed between 2000 and 2017. The more red a tract is, the more that population's shrunk, relative to the tract's total population. Blue-shaded tracts indicate percentage-point increases.

To help you navigate the city’s neighborhoods a bit better, we’ve outlined every tract that has gentrified. There's no universally accepted definition of gentrification, but BuzzFeed News used a methodology developed by Governing magazine and other academic work that relies on census data on income, home prices, and education — but not racial or ethnic demographics. You can read more about how we calculated that here or play around with an interactive map at the end of the article.

Oakland

Gentrification in Oakland has become a focal point as the Bay Area gets increasingly expensive. There have also been viral incidences that made national news, like when a white woman called the police on a black family for having a barbecue.

Below is a map of Oakland that shows just how the historically black city has seen a decrease in its black population, especially in and around gentrifying neighborhoods.

Percentage point change in black population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Percentage point change in white population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Washington, DC

Most gentrified tracts in DC are spread throughout the city’s center, with some recording a decrease in the black population by 69 percentage points. The city has also been singled out by a study as one of the few places where gentrification pushes low-income residents out of the city.

Percentage point change in black population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Percentage point change in white population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Atlanta

Atlanta, sometimes dubbed the “Black Mecca,” has gentrified throughout the center of the city, based on a lot of real estate speculation, the Guardian has reported. In some of these gentrifying census tracts, the black population has shrunk by more than 45 percentage points — with the white population growing by the same amount.

Percentage point change in black population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Percentage point change in white population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

New York City

New York City is a place of block-by-block extremes. As such, the city also gentrified in various boroughs, creating what some scholars at UC Berkeley described as “islands of exclusion in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens.”

Some of the most startling changes in demographics in gentrified neighborhoods can be found in central Brooklyn and northern Manhattan in and around historically black Harlem.

Percentage point change in black population

-30% 30%

New York City

New York City is a place of block-by-block extremes. As such, the city also gentrified in various boroughs, creating what some scholars at UC Berkeley described as “islands of exclusion in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens.”

Some of the most startling changes in demographics in gentrified neighborhoods can be found in central Brooklyn and northern Manhattan in and around historically black Harlem.

Percentage point change in black population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Percentage point change in white population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Baltimore

Unlike other cities, Baltimore saw a displacement of black and white populations in gentrifying neighborhoods. In East Baltimore, where the Latino population grew, white people were displaced in neighborhoods where home values and education levels also increased, a researcher told the Baltimore Sun.

Percentage point change in black population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Percentage point change in white population%22%5D,%22fill-opacity%22:0.8%7D,%22filter%22:%5B%22%3E%22%2C%5B%22get%22%2C%22total_population_17%22%5D%2C10%5D%7D&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoibGFtdm8iLCJhIjoiY2ppMHRoZW03MGR3cjN3bWp2aXNsb3Z2eCJ9.nw6kAxFkEehSx3ttQYxaUg) -30% 30%

-30% 30%

Zoom in and out and toggle between different populations (take a look at the boxes on the top left) with this interactive map:

Gentrified< -30 -25 -20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 >

Black

White

Asian

Hispanic/Latino

Oakland

Atlanta

NYC

DC

Baltimore

© Mapbox © OpenStreetMap Improve this map © Maxar

Notes: The cities were chosen based on how many census tracts gentrified in those cities, whether people were searching for the term “gentrification” in a particular state, and whether the cities had made headlines related to housing issues in recent years.

BuzzFeed News used a methodology adopted from Governing magazine — similar to a methodology developed by Columbia University's Lance Freeman — to determine whether a census tract had gentrified between 2000 and 2017. While opinions differ on what constitutes gentrification, this methodology examines population size, median income, median home values, and post-secondary educational attainment. More details about the methodology and the data can be found here.

Lo Bénichou from Mapbox contributed reporting and editorial production to the article.

Lam Thuy Vo is a reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.

Lam Thuy Vo is a reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.

How China played a part in the birth of globalisation in the 16th century

Globalisation is nothing new, say Peter Gordon and Juan José Morales in a book, The Silver Way, an excerpt from which reveals how a Pacific route to and from Spanish America made China an economic powerhouse 400 years ago

Peter Gordon and Juan José Morales Published:Jan, 2017

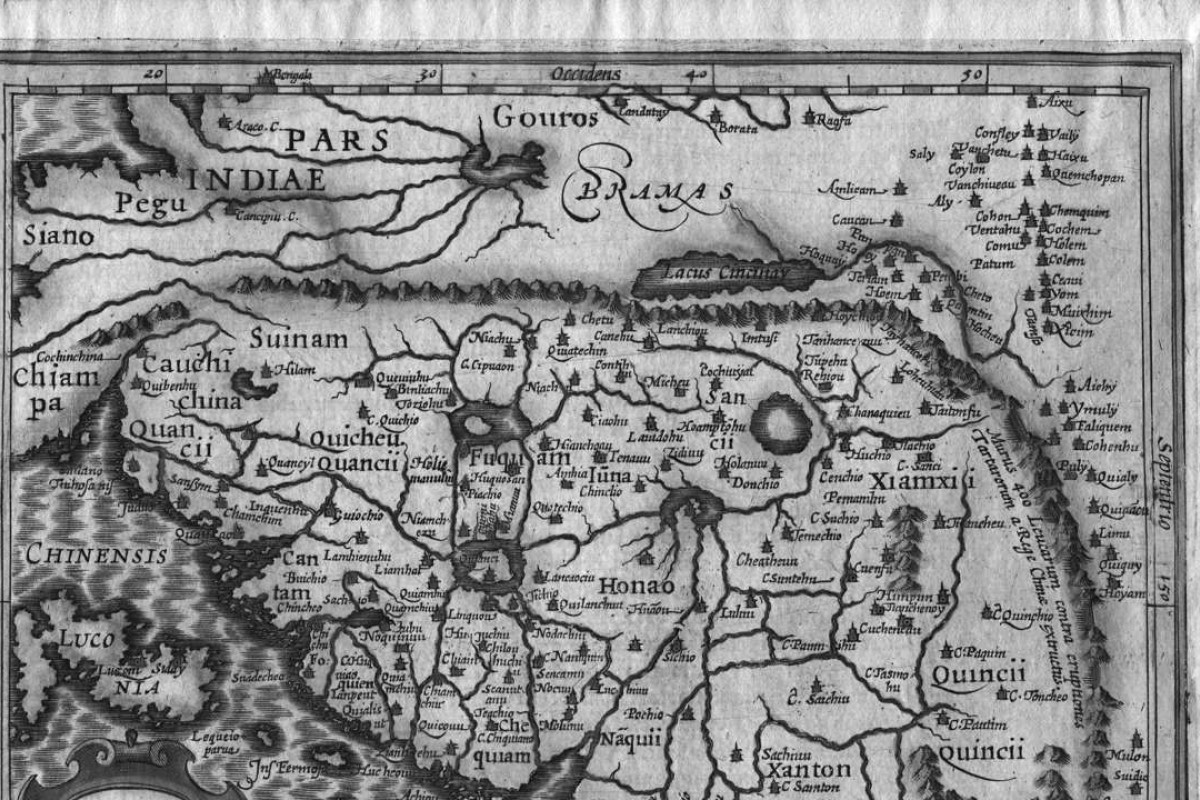

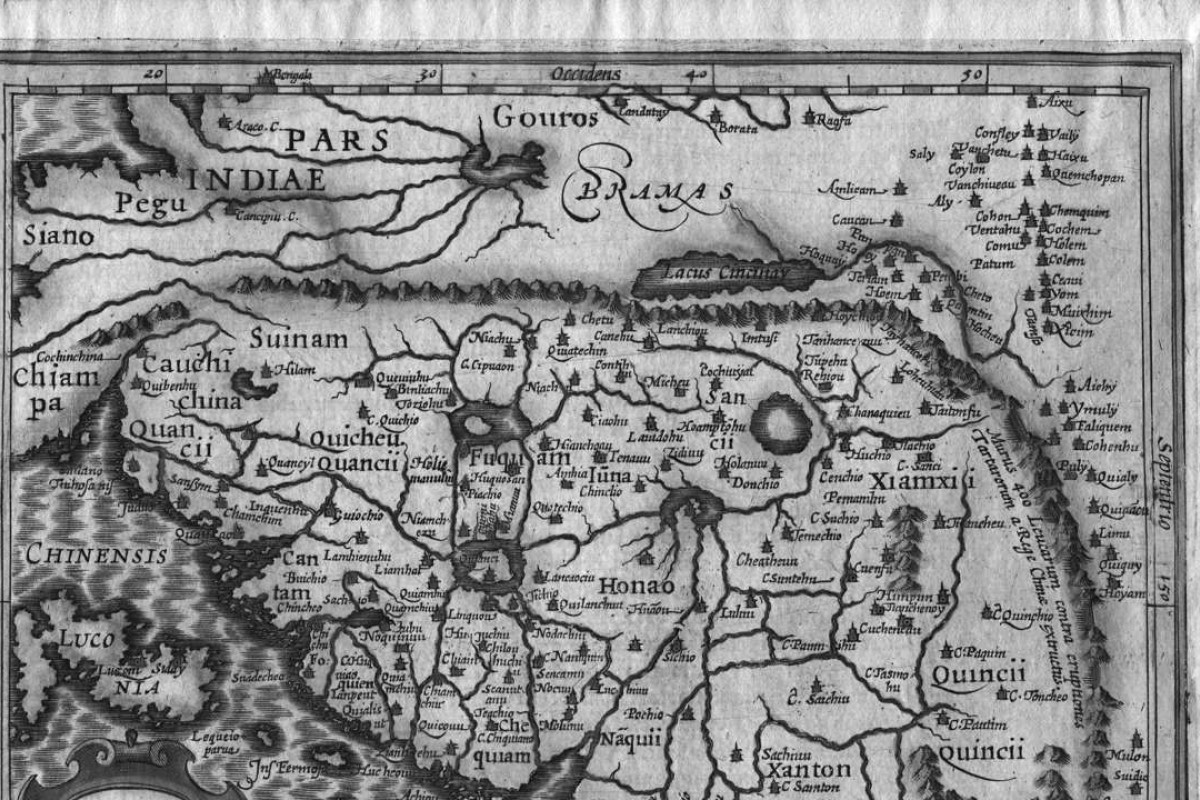

Jodocus Hondius’ 17th-century map of China. From the collection of Juan José Morales.

Long before the greenback there was the Spanish “dollar” and long before New York and London, there was Mexico City. The discovery of a route across the Pacific in the 16th century was a catalyst for the integration of the planet. In a new book, The Silver Way: China, Spanish America and the Birth of Globalisation, 1565-1815 (Penguin Random House North Asia), Hong Kong International Literary Festival founder Peter Gordon and Juan José Morales, a former president of the Spanish Chamber of Commerce in the city, show how the Ruta de la Plata connected China with Spanish America, furthering economic and cultural exchange and building the foundations for the first global currency and the first “world city”.

What follows is an excerpt from the book.

EACH OF THE ELEMENTS THAT characterise globalisation – global trade networks, shipping lines, integrated financial markets, flows of cultures and peoples – can be found in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. A global currency based on the Spanish “dollar” predated the US dollar’s similar role by two centuries. The attributes of today’s world cities typified Mexico 400 years ago.

How to save globalisation from its demise

Globalisation itself, therefore, evidently predates everything that conventional (Anglo-American) wisdom holds necessary for it: the Enlightenment, steam, free trade, laissez-faire capitalism, liberal political systems and the more recent, Western-initiated institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Whatever it is that sustains globalisation cannot be linked to this narrative, for the basic structures of globalisation existed at least two centuries before any of these developments took root.

China’s belt and road can take its cues from the world’s first model of globalisation

Globalisation is a matter of degree, not a binary. But it was during the decidedly Spanish-dominated decades straddling the turn of the 16th century that humanity’s activities first reached a global scale.

This was when the first trade networks united Asia, Europe, the Americas, as well as, it should be added, Africa, with uninterrupted commercial shipping. It was also the period when the world’s financial markets first became linked, through the medium of silver.

An artist’s depiction of the Spanish galleon Samuel.

A century or so later, but well within the Manila galleon period [when trading ships brought the silver from the Americas, through the Philippines, that underpinned China’s money supply], the world’s first global currency emerged in the form of the milled Spanish silver dollar that in turn begat currencies in countries from the United States to China and Japan.

These networks and interactions were not nearly as sophisticated or integrated as those of today, nor were they as fast. After all, the news that Portugal had succeeded in regaining independence from the Spanish crown in December 1640 didn’t reach Macau until May 31, 1642 – much slower than the internet even on a very bad day. But from 1565 on, what happened in China no longer just stayed in China.

China was not just the most economically developed country in the world, it was also the most powerful

Before 1565, the discovery of a mountain of silver affected China only once the metal had travelled through the markets of Europe, the Levant, India and elsewhere. After 1565 [when the Manila galleons began sailing], ingots and coins could be placed in a ship and reach China within months, with minimal intermediaries and mark-ups. It was not quite a telegraphic transfer but neither was it a process of slow diffusion via indirect trade.

Nor were these early-modern networks the result, as today’s are, of deliberate government policy. Indeed, many if not most of the Chinese and Spanish traders were operating contrary to laws and regulations promulgated by their respective emperors: globalisation took root in spite of concerted official efforts to prevent it.

How China exemplifies the double edged sword of globalisation

Globalisation, had anyone stopped to think about it, was hardly a foregone conclusion, however inevitable it looks today. Historian Manel Ollé makes the point that Sino-Spanish interactions in the 16th century were an ambivalent process, intensively commercial but socially and institutionally unstable.

Despite the uncertainty, however, globalisation had the effects one might have expected. In China, overseas demand drove manufacturing and economic growth, which in turn supported the population growth made possible by the innovation in new crops. Financial integration created arbitrage opportunities, which led to more efficient allocation of financial resources; this integration in turn allowed contagion from one economy to another, such as the economic shocks of ship sinkings – a single sinking would knock out a year’s trade.

A battle scene featuring Captain George Anson's ship HMS Centurion fighting a Spanish Manila galleon off the coast of South America, circa 1739-40. Picture: Alamy

The Manila galleons sailed for two-and-a-half centuries, until 1815 and the dawn of a new era of independence for most of Spanish America. The world was during this period a very different place from the one it would later become.

China had the largest, most productive and most dynamic economy in the world. Even a couple of centuries later, Adam Smith would still write in The Wealth of Nations: “China is a much richer country than any part of Europe, and the difference between the price of subsistence in China and in Europe is very great. Rice in China is much cheaper than wheat is anywhere in Europe.”

The 21st century is not the West’s first encounter with a rising China. Nor is this the first time the West has tried unsuccessfully to fit the entire world into a single overarching conceptual framework

China was and still is the factory to the world. During the Manila galleon trade, however, Chinese products were competing not just on price but also on their unsurpassed quality. Consumer-product innovation was mostly an East Asian and largely Chinese monopoly: it was manufacturers in the West – Mexico and then Europe – that copied Asian silks, porcelain, screens, fans and furniture – not the other way around.

The China of the 16th century looked to the West not for development or investment, but rather for the silver needed for the Chinese money supply.

With wounded Russia in retreat, a rising China is riding the waves of globalisation

China was not just the most economically developed country in the world, it was also the most powerful.

Unlike the 1840s, when British ships could force their way up the Pearl River and require China to buy opium, gunboat commerce was not a practical option for the early-modern Europeans in the region. Combining force with commerce was successful only in the Southeast Asian periphery, where, for example, it was Dutch East India Company policy – according to the company’s governor-general in 1614 – that “trade cannot be maintained without war”.

But none of Spain, Portugal or Holland was able to project much force against large, long-standing nations in East Asia. They managed at best only politically insignificant footholds on the coasts of China and Japan, from which they were always in danger of being expelled.

China was able to require that trade take place on its terms, restricted to certain ports.

In Japan, after decades of religious conflict, the Tokugawa rulers decided to expel the Portuguese and closed their borders, except to the Dutch, whom they restricted to the small man-made island of Dejima in 1640, a situation that lasted for more than two centuries, until [the American] Commodore Perry appeared with his black ships in 1853.

More than a century into this period, in 1661, the Chinese rebel leader and Ming loyalist Koxinga ejected the Dutch from Formosa, now Taiwan, and even threatened Manila before he died suddenly the next year.

How China has gone from panda diplomacy to New Silk Road smart power

ASIA’S INTEGRATION INTO GLOBAL MARKETS was, of course, not limited to the Manila galleon trade. In yet another manifestation of globalisation in this early period, Europeans – notably the Portuguese and then the Dutch – soon came to play a major role in Asia’s regional and transcontinental trade. European third-parties transported goods within Asia and also acted as intermediaries in the Chinese-Japanese silver trade.

While this commercial footprint was not itself an indication of military or political power, it probably comes as no surprise that some on the ground harboured such delusions. In 1576, the governor of the Philippines, Francisco de Sande, wrote to Philip II of Spain proposing an invasion of China, which he said “would be very easy”, requiring just a few thousand men:

“The equipments necessary for this expedition are four or six thousand men, armed with lances and arquebuses, and the ships, artillery, and necessary munitions. With two or three thousand men one can take whatever province he pleases, and through its ports and fleet render himself the most powerful on the sea. This will be very easy. In conquering one province, the conquest of all is made. The people would revolt immediately [...] In all the islands a great many corsairs live, from whom also we could obtain help for this expedition, as also from the Japanese, who are the mortal enemies of the Chinese. All would gladly take part in it.”

Portrait of Philip II of Spain by Sofonisba Anguissola.

Philip was having none of it. There is a note in the margin of the report: “Reply as to the receipt of this; and that, in what relates to the conquest of China, it is not fitting at the present time to discuss that matter. On the contrary, he must strive for the maintenance of friendship with the Chinese, and must not make any alliance with the pirates hostile to the Chinese, nor give that nation any just cause for indignation against us.”

De Sande tried again in another letter, in 1579, as did his successor, Diego Ronquillo, a few years later. But the suggestions seem to have fallen on entirely deaf ears. And once the Manila galleons got going, these proposals seem never to have come up again.

Under Donald Trump, the US will accept China’s rise – as long as it doesn’t challenge the status quo

Globalisation was considerably more balanced – economically and politically – between East and West in this first chapter than it was to be in the story’s second. That is not to say, Philip II’s stated intentions notwithstanding, that relations were friendly, or that there was not any protracted shoving. The opportunities for trade and access to raw materials did indeed occasion military action and territorial expansion, but it was the Philippines and the rest of Southeast Asia, rather than the much more powerful China and Japan, that bore the brunt of this.

China was larger in territory, economy and population at the end of this period than at the beginning. The 21st century is not the West’s first encounter with a rising China. Nor is this the first time the West has tried unsuccessfully to fit the entire world into a single overarching conceptual framework. Just as the advance of Western-led globalisation provides the validation for democracy and freedom, these values also become the philosophical justification for globalisation.

Idol worship: why pirate Koxinga is Taiwan's undisputed hero

Sixteenth- and 17th-century globalisation was a consequence rather than an explicit objective of Spanish policy and commerce. But Spanish policy nevertheless had a conceptual framework of its own: Catholicism. To the modern eye, attempts at religious conversion can seem tangential and even detrimental to geopolitical advance and commercial gain. But without questioning the sincere beliefs of the adherents, there was a good deal of realpolitik in advancing Catholicism. Actions, however one-sided, could be presented as being in the interests of the other party. There was a feeling that shared beliefs made it easier to do business.

Globalisation spells the death of minority cultures

Converts also undermined existing hierarchies, loyalties and structures in both occupied territories and other countries. The resulting activities were often considered less than innocent by the governments of China and Japan. Complaints about “interference in internal affairs” are not a uniquely modern phenomenon. The linking of ideology and policy could be a two-edged sword: just as democrats today question realpolitik alliances, Spanish clerics were among the most vociferous opponents of forced labour in colonial mines and agricultural estates.

How the China-US relationship evolved, and why it still matters

Manila galleon-era Spain had a historical narrative of its own: it had been progressively expanding and unifying for centuries – first the reconquista of the Iberian peninsula and then the conquest of an entire new world. Catholicism went hand-in-glove with this territorial and – once the wealth of the Americas came on stream – financial expansion, a success which both validated Catholicism and was in turn justified by it.

Ultimately, the Spanish narrative, not unlike today’s Anglo-American narrative, ran up against the reality that is China. The Sino-Spanish story, and the Silver Way, went into abeyance for 200 years. It is only in the past decade that the stirrings of a possible rebirth can be witnessed.

The Silver Way (Penguin Random House North Asia) is now available now in the Asia-Pacific region and will be in global Amazon stores from June.

COMMENTS

Peter Gordon

Peter Gordon is editor of the Asian Review of Books. A publisher and entrepreneur, he has been active in technology, culture and international trade and investment. He is the co-author of “The Silver Way: China, Spanish America and the Birth of Globalisation, 1565–1815”. He has been a resident of Hong Kong since 1985.

SUPERMOON 2020: WHEN IS THE NEXT RARE FULL MOON SPECTACLE?

An airplane silhouettes against the supermoon on

19 February, 2019 in Nuremberg, southern Germany( AFP/Getty )

A trio of full moons will appear bigger and brighter this Spring

An airplane silhouettes against the supermoon on

19 February, 2019 in Nuremberg, southern Germany( AFP/Getty )

A trio of full moons will appear bigger and brighter this Spring

Anthony Cuthbertson Friday 21 February 2020

Three successive supermoons this Spring will give sky gazers the opportunity to witness the rare spectacle for an entire season in 2020.

Each month between March and May, the full moon will be near to its closest point to Earth in its orbit, making it appear bigger and brighter than usual.

The first of these supermoons takes place on 9 March, when the full moon passes at 357,404km (222,081 miles) from Earth.

On 8 April, the full moon passes even closer at just 357,035km, making it the closest a full moon has been to Earth since February last year.

Weather permitting, this will be the most impressive supermoon of 2020, with the final supermoon on 7 May passing at 361,184km from Earth.

Super blood wolf moon totally eclipses the sun: in pictures

An effect called the "Moon illusion" means that the moon will appear even bigger when it is rising or setting over the horizon and there are objects like trees or buildings within the line of sight.

"Because these relatively close objects are in front of the moon, our brain is tricked into thinking the moon is much closer to the objects that are in our line of sight," explained Mitzi Adams, a solar scientist at Nasa's Marshall Space Flight Center.

"At moon rise or set, it only appears larger than when it is directly overhead because there are no nearby objects with which to compare it."

A full moon passes behind The Shard skyscraper on

9 September, 2014 in London, England (Getty Images)

A full moon passes behind The Shard skyscraper on

9 September, 2014 in London, England (Getty Images)

A supermoon earlier this month conincided with Storm Ciara in the UK, meaning viewing conditions were severely affected for people in the UK.

Long range forecasts from the Met Office suggest March's supermoon will be accompanied by more favourable weather, especially in the south of the country.

"A continuation of the unsettled weather is expected at first, with spells of rain and strong winds broken by brighter but showery conditions," the weather service states on its website.

"The heaviest rain and strongest winds are expected in the northwest, with drier conditions expected in southern and eastern parts. It will perhaps become more generally settled by the middle of March, with more prolonged dry spells possible, especially in the south."

'I won't stay silent': Whistleblower reveals how TONNES of facemasks, hand sanitisers and other coronavirus supplies were shipped from Australia to China as the deadly bug took hold

Whistleblower tells of how he saw medical supplies repacked and sent to China

'If essential medical items leave the country, what's left for us?' he said

Global shortage hits leaving Australian doctors without facemasks, protection

WHO flagged global shortage on February 7. Government banned export April 1

CHINA NEEDED SUPPLIES HOW IT GOT THEM WAS UNDER THE TABLE IN MANY COUNTRIES, GOING AROUND RED TAPE TO GET THE GOODS, NOW THEY SELL THEM BACK TO THOSE SAME COUNTRIES

By ALISON BEVEGE FOR DAILY MAIL AUSTRALIA PUBLISHED: 5 April 2020

A whistleblower has revealed how he watched essential medical equipment being purchased from Australian pharmacies then shipped to China during the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic.

Greenland Group, which manages property developments across the globe with the support of the Chinese government, told employees at its Sydney office in January to stop their normal work.

Instead, they were tasked with sourcing face masks, hand sanitisers, thermometers and other medical items, storing them at their office and shipping them to China.

One of the company's workers told 60 Minutes he felt uncomfortable and suspicious watching board rooms fill up with emergency equipment being repackaged for export.

Man reveals he saw tonnes on facemasks being shipped to China

'I think in a time of crisis, we all have a responsibility to do something, and I felt that I had to do something,' he said.

'It just didn't sit with me that this type of thing could happen. I couldn't just watch it and just stay silent.'

Medical experts are desperately worried about a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) that is already leaving frontline medical staff exposed to coronavirus infection.

Australia's supply of face masks had already been depleted by the bushfire crisis when the coronavirus pandemic took off in Wuhan, China.

Pallets of medical equipment being shipped to China by property developers Risland Australia, another Beijing-backed firm that repurposed staff to buy up supplies for China

Pallets of medical equipment being shipped to China by property developers Risland Australia, another Beijing-backed firm that repurposed staff to buy up supplies for China

Risland sent 90 tonnes of medical supplies bought in Australia back to China in February

As the pandemic began to take hold in Australia, bulk supplies of vital medical items were shipped from Sydney to China at the request of Beijing-backed Greenland Group.

'It definitely rose my suspicion think the main concern was if all of these essential medical items leave the country, what's left for us?' the Greenland whistleblower said.

'It is very unsettling that essential equipment can just leave our borders in massive commercial quantities

Greenland Group was not the only Chinese-backed company to buy up Australian supplies.

Chinese real estate developer Poly Developments and Holdings told staff at the Sydney office in Australia Square to check local pharmacies for N95 surgical face masks or 8210 masks.

The heavy-duty waterproof protective equipment that medical workers are using overseas to deal with coronavirus, that Australian health care workers can only dream about

The heavy-duty waterproof protective equipment that medical workers are using overseas to deal with coronavirus, that Australian health care workers can only dream about

The staff replied they were searching the city from Eastwood to Hornsby, Penrith and Mona Vale.

In February, another Chinese property developer, Risland Australia, shipped 90 tonnes of medical protection equipment to China.

Risland made an online post last month saying '90 tonnes of selective medical supplies' were sent 'air transport direct from Sydney to Wuhan via corporate jet'.

Video footage also emerged showed boxes of surgical masks being stacked up at a Perth airport before being sent to Wuhan on February 8 - when there were 15 cases of coronavirus in Australia.

China makes most of the world's protective equipment after globalisation shifted manufacturing to the low-cost producer. Workers at a face mask production line on March 30 in Longyan, Fujian Province (pictured). China has seized production at a number of factories

China makes most of the world's protective equipment after globalisation shifted manufacturing to the low-cost producer. Workers at a face mask production line on March 30 in Longyan, Fujian Province (pictured). China has seized production at a number of factories

China did not just tell its companies in Australia to buy up medical supplies - the Chinese Communist Party's affiliates were buying up supplies around the world.

In two months, China amassed an estimated 2.4 billion pieces of protective equipment including more than 2 billion masks, 60 Minutes reported.

At the same time it seized production at factories producing protective equipment for export to countries around the world.

Chinese property developers Greenland sent staff out to buy the medical supplies (pictured). A whistleblower has revealed how he felt so uncomfortable he just had to take action

Chinese property developers Greenland sent staff out to buy the medical supplies (pictured). A whistleblower has revealed how he felt so uncomfortable he just had to take action

The whistleblower told 60 Minutes how suspicious he felt watching the boxes of medical supplies being unpacked and repacked in the staff room, board room and lunch room

The whistleblower told 60 Minutes how suspicious he felt watching the boxes of medical supplies being unpacked and repacked in the staff room, board room and lunch room

Face mask manufacturer Medicom Group's president of North American operations Guillaume Laverdure said the Chinese Government had requisitioned three factories in China and one in Shanghai.

'So the government sent people to take control of the inventory and the products in our factory,' Mr Laverdure told 60 Minutes.

CORONAVIRUS CASES IN AUSTRALIA: 5,688

New South Wales: 2,580

Victoria: 1,135

Queensland: 907

Western Australia: 453

South Australia: 409

Australian Capital Territory: 96

Tasmania: 82

Northern Territory: 26

TOTAL CASES: 5,688

DEAD: 35

The coronavirus crisis has revealed the weakness of a globalised supply chain which has left Australia reliant on imports, stripped of its capacity to make lifesaving equipment in the face of a deadly pandemic.

By allowing importers to undercut domestic manufacturers, Australia lost the ability to make its own masks and all the manufacturing capacity moved to low-cost China.

World Health Organisation director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus had sounded the alarm on the global shortage of protective equipment on February 7, even as Chinese companies were stripping Australian pharmacies of masks.

'The world is facing severe disruption in the market for personal protective equipment,' Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus told a televised press conference from Geneva.

'Global stocks of masks and respirators are now insufficient to meet the needs of WHO and our partners.'

Dr Tedros's announcement came just two weeks after Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt toured the national medical stockpile, posting pictures on Twitter to reassure the Australian public that with 20 million single-use masks, Australia did not have a shortage.

How bulk supplies of Australia's face masks, hand sanitisers and other vital medical items were shipped to CHINA as the coronavirus pandemic took hold

Bulk supplies of vital medical items were shipped from Sydney to China at the request of a Beijing-backed property giant as the coronavirus pandemic took hold in Australia.

Greenland Group, which manages property developments across the globe with the support of the Chinese government, told employees at its Sydney office to stop their normal work in January.

Instead, they were tasked with sourcing face masks, hand sanitisers, thermometers and other medical items, storing them at their office and shipping them to China.

A whistleblower told The Sydney Morning Herald the exercise was a worldwide effort and continued until the end of February.

'Basically all employees, the majority of whom are Chinese, were asked to source whatever medical supplies they could,' the insider said.

'There were numerous requests from the HR manager and even our direct reporting line [which] prioritised the assisting of the company in gathering these supplies over other work activities.'

Greenland Group told Chinese language media in Australia the company collected three million protective masks, 700,000 hazmat suits and 500,000 pairs of medical gloves during the global effort.

It is unclear how many of those were sourced in Australia.

Greenland Group confirmed the shipments from Sydney to China in a statement to Daily Mail Australia, saying it 'felt compelled' to assist 'in efforts to mitigate the spread of the virus, which had caused a shortage of critical medical supplies in China'.

Greenland Group confirmed the shipments from Sydney to China in a statement to Daily Mail Australia, saying it 'felt compelled' to assist 'in efforts to mitigate the spread of the virus, which had caused a shortage of critical medical supplies in China'.

The supplies were 'dispatched to China, which at that time was the epicentre of the outbreak', the statement read.

'As such, Greenland Group initiated a drive for medical supplies, and provided accommodation services for front-line medical staff in China via the company's hotel group.

'Greenland Australia supported Greenland Group's initiative by arranging for medical supplies to be dispatched to China. Again, it should be noted that this proactive response occurred in late January and early February, at a time when the worldwide spread of the virus, and all response efforts, were focused on China.'

Photos show pallet-loads of medical items stored in company-stamped boxes at Greenland's Sydney offices and at various airports.

Sherwood Lou, Greenland Australia's managing director, shared photos of the supplies on February 13.

He wrote at the time: 'The second batch of non-contact forehead thermometers will soon take off to China! Coronavirus situation is serious, Chinese people, local and overseas, are trying their best, fighting together to combat the virus.'

Greenland Group told Chinese language media in Australia the company collected three million protective masks, 700,000 hazmat suits and 500,000 pairs of medical gloves during the global effort

Greenland Group told Chinese language media in Australia the company collected three million protective masks, 700,000 hazmat suits and 500,000 pairs of medical gloves during the global effort

Everything you need to know about coronavirus explained

The company has sold a billion dollars worth of property in Sydney and Melbourne since its 2013 arrival to Australia.

Meanwhile, the Federal Government is scrambling to produce enough medical supplies as confirmed local coronavirus cases surge to more than 2,400 - and doubling about every three days.

Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt said a 'war production unit' had been convened at the weekend to prepare Australia.

The Federal Government is scrambling to produce enough medical supplies as confirmed local coronavirus cases surge to more than 2,400. Pictured: Two young women in face masks walk along Circular Quay in Sydney on Wednesday

The Federal Government is scrambling to produce enough medical supplies as confirmed local coronavirus cases surge to more than 2,400. Pictured: Two young women in face masks walk along Circular Quay in Sydney on Wednesday

'We have four companies that have indicated that they are willing to make ventilators and will be seeking approvals which have been given at light speed,' he told Nine News on Monday.

'At the same time, we are working on imports and procurements, large volumes of masks have arrived over the course of the weekend, additional volumes of testing kits.'

Australia has only one face mask factory in operation, The Med-Con in Shepparton, a regional area of northern Victoria.

It is facing an unprecedented demand to make face masks and hospital gowns during the crisis.

Health Minister Greg Hunt toured a national medical supply warehouse on January 24, saying Australia had 20 million single-use face masks. The WHO announced a global shortage of personal protective equipment on February 7

Health Minister Greg Hunt toured a national medical supply warehouse on January 24, saying Australia had 20 million single-use face masks. The WHO announced a global shortage of personal protective equipment on February 7

Pictured: Australian-based Chinese property company Risland

shipped 90 tonnes worth of vital medical supplies to Wuhan

Pictured: Australian-based Chinese property company Risland

shipped 90 tonnes worth of vital medical supplies to Wuhan

Risland made an online post last month that declared their support for Wuhan and showed workers inside a warehouse packed with thousands of boxes of protective clothing (pictured)

Risland made an online post last month that declared their support for Wuhan and showed workers inside a warehouse packed with thousands of boxes of protective clothing (pictured)

Sydney anaesthetist Robert Hackett risked his job to speak out about the protective equipment shortage now facing frontline medical staff in major Australian hospitals.

As 60 Minutes reporter Liz Hayes demonstrated how all the wall-mounted dispensers were empty of hand sanitiser, Dr Hackett told of how staff were having to reuse single-use masks while others had no masks at all.

'The equipment we do have is pretty much not much more than a plastic flimsy gown at times ... we're desperate to get these things on the frontline as soon as possible,' he said.

'Many of my colleagues have purchased hooded gowns and other bits of equipment from Bunnings and have even pleaded for other people to go to Bunnings and buy these bits of equipment - I mean we are desperate, none of us ever signed up for this.'

Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton said on Wednesday April 1 that the government had banned the export of essential medical supplies such as masks, gloves, gowns, goggles, visors or alcohol wipes, as well as hand sanitiser.

Anyone caught exporting the goods may face up to five years' jail under the new amendment to the Customs (Prohibited Exports) Regulations 1958 Act called 'COVID-19 Human Biosecurity Emergency'.

GREENLAND AUSTRALIA STATEMENT IN FULL

Greenland Australia can confirm that in late January and early February 2020, the company organised shipments of medical supplies to Greenland Group's global head office in Shanghai, to help contain the rapidly-developing coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak in China.

At this time, China was the epicentre of the outbreak, and Greenland Australia's efforts corresponded with those of many other companies and individuals around the world organising similar donations.

Greenland Australia's parent company, Greenland Group, felt compelled, as a major international company, to assist in efforts to mitigate the spread of the virus, which had caused a shortage of crucial medical supplies in China.

As such, Greenland Group initiated a drive for medical supplies, and provided accommodation services for front-line medical staff in China via the company's hotel group.

Greenland Australia supported Greenland Group's initiative by arranging for medical supplies to be dispatched to China.

Again, it should be noted that this proactive response occurred in late January and early February, at a time when the worldwide spread of the virus, and all response efforts, were focussed on China.

However, Greenland Australia also recognises that Australian people are currently at risk, and with the more recent and ongoing domestic spread of COVID-19, the company is focussed on helping people in this country, just as Australia's many friends around the world are doing.

Greenland Australia continues to take this pandemic very seriously, and in conjunction with Greenland Group, we will continue to do everything we can to assist.

Read more:

Coronavirus: 'Vital medical supplies sent to China' as export ban comes 'too late', Aussie hospitals grapple with shortages