How World War II got Japan and the US hooked on amphetamines, ‘the ultimate military performance enhancing drug’

In this second excerpt of Peter Andreas’ book Killer High, the author recounts how a post-war surplus of the drug triggered addiction epidemics on both sides of the Pacific

Published: 23 Feb, 2020

https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/3051418/how-world-war-ii-got-japan-and-us-got-hooked

In The Art of War , Sun Tzu wrote that speed is “the essence of war”. While he, of course, did not have amphetamines in mind, he would no doubt have been impressed by their powerful war-facilitating psychoactive effects. Amphetamines – often called “pep pills”, “go pills”, “uppers” or “speed” – are a group of synthetic drugs that stimulate the central nervous system, reducing fatigue and appetite and increasing wakefulness and a sense of well-being.

Methamphetamine is a particularly potent and addictive form of the drug, best known today as “crystal meth”. All amphetamines are now banned or tightly regulated. The quintessential drug of the modern industrial age, amphetamines arrived relatively late in the history of mind-altering substances – commercialised just in time for mass consumption during World War II by the leading industrial powers.

In this second excerpt of Peter Andreas’ book Killer High, the author recounts how a post-war surplus of the drug triggered addiction epidemics on both sides of the Pacific

Published: 23 Feb, 2020

https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/3051418/how-world-war-ii-got-japan-and-us-got-hooked

In The Art of War , Sun Tzu wrote that speed is “the essence of war”. While he, of course, did not have amphetamines in mind, he would no doubt have been impressed by their powerful war-facilitating psychoactive effects. Amphetamines – often called “pep pills”, “go pills”, “uppers” or “speed” – are a group of synthetic drugs that stimulate the central nervous system, reducing fatigue and appetite and increasing wakefulness and a sense of well-being.

Methamphetamine is a particularly potent and addictive form of the drug, best known today as “crystal meth”. All amphetamines are now banned or tightly regulated. The quintessential drug of the modern industrial age, amphetamines arrived relatively late in the history of mind-altering substances – commercialised just in time for mass consumption during World War II by the leading industrial powers.

Few drugs have received a bigger stimulus from war. As Lester Grinspoon and Peter Hedblom wrote in their 1975 study The Speed Culture, “World War II probably gave the greatest impetus to date to legal medically authorised as well as illicit black market abuse of these pills on a worldwide scale.” The story of this drugs-war relationship is therefore mostly about the proliferation of synthetic stimulant use during World War II and its speed-fuelled aftermath.

While produced entirely in the laboratory, amphetamines owe their existence to the search for an artificial substitute for the ma-huang plant, better known in the West as ephedra. (AKA MORMON TEA) This relatively scarce desert shrub had been used as a herbal remedy for more than 5,000 years in China, where it was often ingested to treat common ailments such as coughs and colds and to promote concentration and alertness, including by night guards patrolling the Great Wall of China.

Japanese chemist Nagayoshi Nagai.

Japanese chemist Nagayoshi Nagai.

In 1887, Japanese chemist Nagayoshi Nagai successfully extracted the plant’s active ingredient, ephedrine, which closely resembled adrenaline, and in 1919, another Japanese scientist, Akira Ogata, developed a synthetic substitute for ephedrine. But it was not until amphetamine was synthesised in 1927, at a University of California at Los Angeles laboratory by young British chemist Gordon Alles, that a formula became available for commercial medical use.

Alles sold this formula to Philadelphia pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline & French, which brought it to the market in 1932 as the Benzedrine inhaler (an over-the-counter product to treat asthma and congestion) before introducing it in tablet form a few years later. “Bennies” were widely promoted as a wonder drug for all sorts of ailments, from depression to obesity, with little apparent concern or awareness of their addictive potential and the risk of longer-term physical and psychological damage. And with the outbreak of another world war, it did not take long for such large-scale pill pushing to also reach the battlefield.

The Japanese imperial government sought to give its fighting capacity a pharmacological edge, contracting out methamphetamine production to domestic pharmaceutical companies for use during World War II. The tablets, under the trade name Philopon (also known as Hiropin), were distributed to pilots for long flights and to soldiers for combat. In addition, the government gave munitions workers and those labouring in other factories methamphetamine tablets to increase their productivity. The Japanese called the war stimulants senryoku zokyo zai, or “drug to inspire the fighting spirits”.

Workers in the defence industry and other war-related fields were compelled to take drugs to help boost their output. Strong pre-war inhibitions against drug use were pushed aside. The introduction of what is now the illegal drug of choice in Japan therefore began with state-promoted use during the second world war.

It is not difficult to understand the appeal of methamphetamines in wartime Japan. Total war required total mobilisation, from factory to battlefield. Pilots, soldiers, naval crews and labourers were all pushed beyond their natural limits to stay awake longer and work harder. As one group of scholars notes, in Japan, “taking stimulants to enhance performance was a mark of patriotism”.

Kamikaze pilots in particular took large doses of methamphetamine via injection before their suicide missions. They were also given pep pills stamped with the crest of the emperor. These consisted of methamphetamine mixed with green-tea powder and were called Totsugeki-Jo or Tokkou-Jo, known otherwise as “storming tablets”. Most kamikaze pilots were young men, often in their late teens. Before they received their injection of Philopon, the pilots undertook a warrior ceremony in which they were presented with sake, wreaths of flowers and decorated headbands.

A kamikaze pilot tries to crash his plane loaded with bombs onto the deck of a US warship. Photo: Getty Images

A kamikaze pilot tries to crash his plane loaded with bombs onto the deck of a US warship. Photo: Getty Images

Although soldiers on all sides in World War II returned home with an amphetamine habit, the problem was most severe in Japan, which experienced the first drug epidemic in the country’s history. Many soldiers and factory workers who had become hooked on the drug during the war continued to consume it post-war. Users could get their hands on amphetamines because the Imperial Army’s post-war surplus had been dumped into the domestic market.

At the time of its surrender in 1945, Japan had massive stockpiles of Hiropin in warehouses, military hospitals, supply depots and caves scattered throughout the islands. Some of the supply was sent to public dispensaries for distribution as medicine, but the rest was diverted to the black market rather than destroyed. The country’s Yakuza crime syndicate took over much of the distribution, and the drug trade would eventually become its most important source of revenue. Any tablets not diverted to illicit markets remained in the hands of pharmaceutical companies

The drug companies mounted advertising campaigns to encourage consumers to purchase the over-the-counter medicine. Sold under the name “wake-a-mine”, the product was pitched as offering “enhanced vitality”. According to one journalist, these companies also sold “hundreds of thousands of pounds” of “military-made liquid meth” left over from the war to the public, with no prescription required to purchase the drug. With an estimated 5 per cent of Japanese between the ages of 18 and 25 taking the drug, many became intravenous addicts. The presence of United States military bases on the islands contributed to the epidemic.

National newspaper Asahi wrote that US servicemen were responsible for spreading amphetamine use from large cities to small towns. Indeed, the country’s Narcotics Section arrested 623 American soldiers for drug trafficking in 1953. However, most drug scandals involving US soldiers garnered little coverage by the major papers out of “deference” to “American-Japanese friendship”.

By 1954, there were 550,000 illicit amphetamine users in Japan. This epidemic led to strict state regulation of the drug. The 1951 Stimulant Control Law banned methamphetamine possession, and penalties for the offence were increased in 1954. In 1951, some 17,500 people were arrested for amphetamine abuse, and by 1954 the number had spiked to 55,600. During the early 1950s, arrests in Japan for stimulant offences made up more than 90 per cent of total drug arrests. In a 1954 Ministry of Welfare anonymous survey, 7.5 per cent of respondents reported having sampled Hiropon. Meanwhile, the Asahi published an estimate that 1.5 million Japanese used methamphetamine in 1954.

US troops in the Korean War. Photo: Getty Images

The high rates of amphetamine use in Japan began to subside by the late 1950s and early 1960s as economic growth began to create jobs. Nevertheless, it is striking that methamphetamine would remain the most popular illicit drug in Japan for decades to come. Germany, meanwhile, did not experience the same post-war surge in stimulant use found in Japan, in part because the occupation dismantled domestic production.

The area where Temmler Werke had produced Pervitin came under Soviet occupation, and the factory was expropriated. At the same time, American pharmaceutical companies bought up the firm’s production facilities in the western zones, and it would take years for Temmler Werke to restart production in its new Marburg location. Moreover, Germany had already imposed tighter controls on Pervitin during the war, making it less accessible even before the war came to an end.

In contrast to tapering off in post-war Germany, amphetamine consumption in the US took off. Pharmacologist Leslie Iversen writes that “the non-medical use of amphetamines spread rapidly in the 20 years after the second world war. This was partly due to the attitude of the medical community to these drugs, which continued to view them as safe and effective medicines, and partly due to the widespread exposure of US military personnel to D-amphetamine during the war”.

By the late 1950s, pharmaceutical companies in the US were legally manufacturing 3.5 billion tablets annually – equivalent to 20 doses of five to 15 milligrams for every American. Of all major powers in the decades after World War II, the US stood out for its continued heavy military use of speed. Indeed, although amphetamines had been widely available to US service members during World War II, they became standard issue during the Korean war (1950-1953).

Smith, Kline & French was more than happy to be the supplier of choice once again, although this time it was supplying the military with dextroamphetamine (sold under the brand name Dexedrine), which was almost twice as potent on a milligram basis as the Benzedrine used during World War II. The manufacturer insisted that the drug had no negative side effects and was non-addictive.

US troops in the Korean War. Photo: Getty Images

The high rates of amphetamine use in Japan began to subside by the late 1950s and early 1960s as economic growth began to create jobs. Nevertheless, it is striking that methamphetamine would remain the most popular illicit drug in Japan for decades to come. Germany, meanwhile, did not experience the same post-war surge in stimulant use found in Japan, in part because the occupation dismantled domestic production.

The area where Temmler Werke had produced Pervitin came under Soviet occupation, and the factory was expropriated. At the same time, American pharmaceutical companies bought up the firm’s production facilities in the western zones, and it would take years for Temmler Werke to restart production in its new Marburg location. Moreover, Germany had already imposed tighter controls on Pervitin during the war, making it less accessible even before the war came to an end.

In contrast to tapering off in post-war Germany, amphetamine consumption in the US took off. Pharmacologist Leslie Iversen writes that “the non-medical use of amphetamines spread rapidly in the 20 years after the second world war. This was partly due to the attitude of the medical community to these drugs, which continued to view them as safe and effective medicines, and partly due to the widespread exposure of US military personnel to D-amphetamine during the war”.

By the late 1950s, pharmaceutical companies in the US were legally manufacturing 3.5 billion tablets annually – equivalent to 20 doses of five to 15 milligrams for every American. Of all major powers in the decades after World War II, the US stood out for its continued heavy military use of speed. Indeed, although amphetamines had been widely available to US service members during World War II, they became standard issue during the Korean war (1950-1953).

Smith, Kline & French was more than happy to be the supplier of choice once again, although this time it was supplying the military with dextroamphetamine (sold under the brand name Dexedrine), which was almost twice as potent on a milligram basis as the Benzedrine used during World War II. The manufacturer insisted that the drug had no negative side effects and was non-addictive.

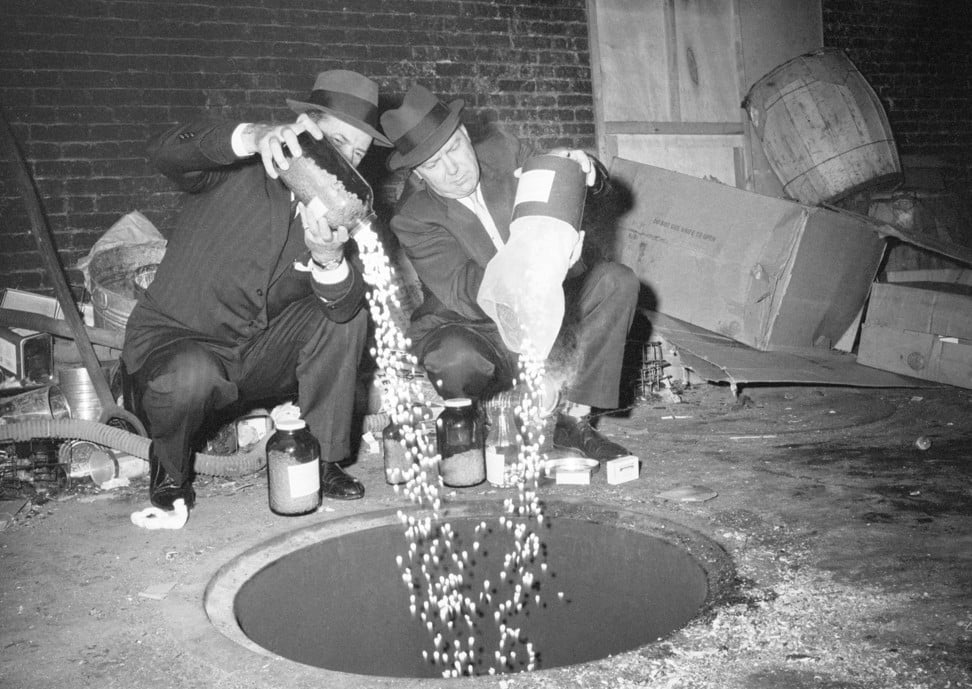

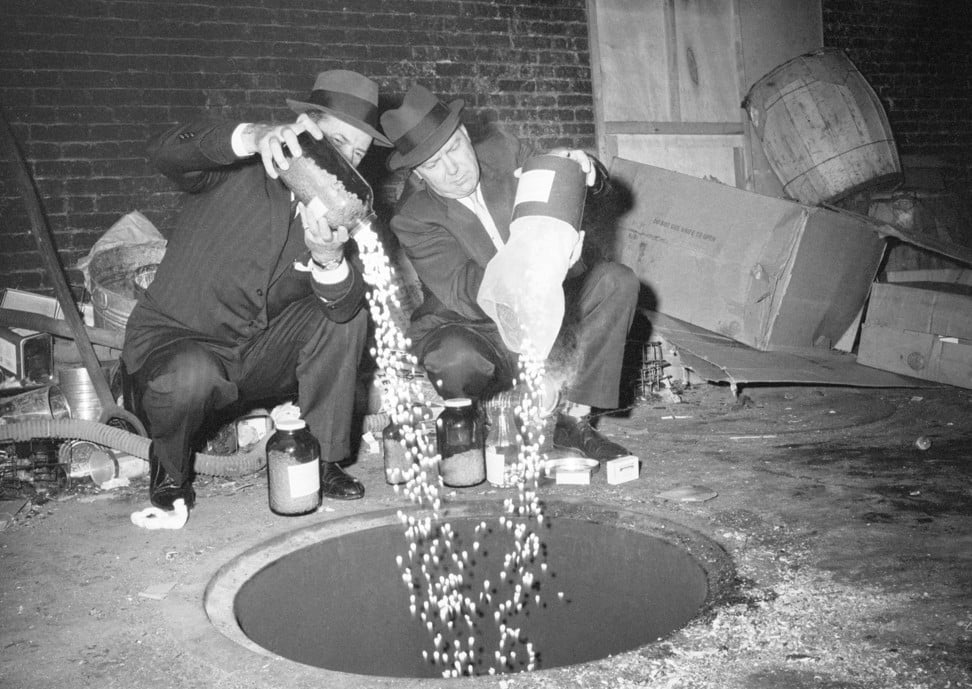

Police officers in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, pour 15,000 amphetamine pills into the city incinerator, in 1960. Photo: Getty Images

In addition to coming home hooked on speed, some servicemen returning from the Korean war also introduced to the US new methods of ingesting the drug. Dr Roger Smith, who ran the Amphetamine Research Project at the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic, notes that the first reported case of Americans engaging in intravenous methamphetamine abuse involved servicemen based in Korea and Japan in the early 1950s. It is perhaps no coincidence that East Asia was at that time “awash in supplies of liquid meth left over from World War II”.

Police officers in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, pour 15,000 amphetamine pills into the city incinerator, in 1960. Photo: Getty Images

In addition to coming home hooked on speed, some servicemen returning from the Korean war also introduced to the US new methods of ingesting the drug. Dr Roger Smith, who ran the Amphetamine Research Project at the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic, notes that the first reported case of Americans engaging in intravenous methamphetamine abuse involved servicemen based in Korea and Japan in the early 1950s. It is perhaps no coincidence that East Asia was at that time “awash in supplies of liquid meth left over from World War II”.

Returning soldiers may have been some of the first to build meth labs in the US. Following numerous arrests in 1962 of California doctors who were illegally prescribing injectable methamphetamine to patients, and pharmaceutical companies’ voluntary withdrawal of the drug from stores, those looking for a profit or a fix came up with a solution. Several Korean war veterans reportedly got together in the San Francisco Bay Area to build the first meth labs to take advantage of the scarcity of the drug after the recall of Methedrine and Desoxyn.

High levels of amphetamine use among the US armed forces persisted into

the Vietnam war. Although the recommended dose was 20 milligrams of Dexedrine for 48 hours of combat-readiness, the reality was that the drug was handed out, as one soldier put it, “like candies”, with little attention to dosage or frequency of use.

Elton Manzione, a member of a long-range reconnaissance platoon, acknowledged: “We had the best amphetamines available and they were supplied by the US government.” A navy commando noted, “When I was a SEAL team member in Vietnam, the drugs were routinely consumed. They gave you a sense of bravado as well as keeping you awake. Every sight and sound was heightened. You were wired into it all and at times you felt really invulnerable.”

The US military supplied its troops with more than 225 million doses of Dexedrine (and the French-manufactured Obestol) during the war. Soldiers could also buy amphetamine over the counter in many cities and towns in Vietnam. Grinspoon and Hedblom argue that all the attention given to illicit drug consumption by soldiers during the Vietnam war glossed over the more severe problem of amphetamine addiction.

US Army helicopters attack a Viet Cong camp, in 1965. Photo: AP

A key source of information on amphetamine use in Vietnam was the 1971 Inquiry into Alleged Drug Abuse in the Armed Services, a report of the House of Representatives Committee on Armed Services. The report noted that due to increased safety concerns, amphetamines had been removed from survival kits by 1971, and prescriptions of these drugs had sharply declined: in 1966, the US Navy issued the equivalent of 33 million 10-milligram capsules of amphetamine, but by 1970 this number had dropped to 7 million capsules. Though these numbers demonstrated reductions in usage over time, they also revealed the high rates of amphetamine use in the US military during the Vietnam war.

According to another report published in 1971, The Fourth Report by the Select Committee on Crime, “Over the past four years, the Navy seems to have required more stimulants than any other branch of the services. Their annual, active duty, pill-per-person requirement averaged 21.1 during the years 1966-69. The Air Force has flown almost as high by requiring 17.5 10-milligram doses per person in those years. The Army comes in last, averaging 13.8 doses per person per year.”

US Army helicopters attack a Viet Cong camp, in 1965. Photo: AP

A key source of information on amphetamine use in Vietnam was the 1971 Inquiry into Alleged Drug Abuse in the Armed Services, a report of the House of Representatives Committee on Armed Services. The report noted that due to increased safety concerns, amphetamines had been removed from survival kits by 1971, and prescriptions of these drugs had sharply declined: in 1966, the US Navy issued the equivalent of 33 million 10-milligram capsules of amphetamine, but by 1970 this number had dropped to 7 million capsules. Though these numbers demonstrated reductions in usage over time, they also revealed the high rates of amphetamine use in the US military during the Vietnam war.

According to another report published in 1971, The Fourth Report by the Select Committee on Crime, “Over the past four years, the Navy seems to have required more stimulants than any other branch of the services. Their annual, active duty, pill-per-person requirement averaged 21.1 during the years 1966-69. The Air Force has flown almost as high by requiring 17.5 10-milligram doses per person in those years. The Army comes in last, averaging 13.8 doses per person per year.”

Grinspoon and Hedblom point out that these figures suggest that from 1966 to 1969, members of the US Army alone took more amphetamines than all British or American armed forces in the second world war. They note that even as the military launched a campaign against heroin, it continued to overlook amphetamine use, and indeed routinely supplied the drug to the troops in Southeast Asia as late as 1973.

In the following years, even as amphetamines came to be tightly controlled at home, the US Air Force kept dispensing them to pilots. Dexedrine was given to the crews of F-111 aircraft for their 13-hour-long missions to Libya during Operation El Dorado Canyon in mid-April 1986. The drug was again given out in late December 1989 during Operation Just Cause in Panama, and during the 1990-1991 Gulf War, almost two-thirds of fighter jet pilots in Operation Desert Shield and more than half in Operation Desert Storm took amphetamines.

Operations Desert Shield and Storm saw the deployment of aircraft from the continental United States to the Arabian Peninsula, a trip that required a 15-hour flight across five to seven time zones. One pilot admitted, “Without go pills I would have fallen asleep maybe 10 to 15 times.” In 1991, Air Force Chief of Staff General Merrill McPeak temporarily banned amphetamines, saying the pills were no longer needed with the ending of combat operations in Iraq. But in 1996, Air Force Chief of Staff John Jumper quietly reversed the ban.

Short of an unlikely epidemic of [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder] among our soldiers, the military almost certainly uses the stimulants to help fatigued and sleep-deprived troops stay alert and awakeRichard A. Friedman, psychiatrist

At the turn of the century, supplying amphetamines to US aircrews remained standard practice, though the air force had its crews sign a consent form emphasising that taking the pills was voluntary. The form appeared to both leave the decision of whether to take Dexedrine up to the pilot and compel the pilot to take the medication with him on the flight.

A study of dextroamphetamine use during B-2 combat missions in Operation Iraqi Freedom revealed high rates of amphetamine use among pilots. The pilots flew B-2 bombers from either Whiteman Air Force Base in Montana or a forward deployed location to targets in Iraq. Pilots on the shorter missions used dextroamphetamine on 97 per cent of their sorties, while those on the longer missions used the drug in 57 per cent of sorties. The puzzling difference between these two rates was partly explained by the fact that napping was more often possible on longer flights, reducing pilots’ need for the drug.

Moreover, the US military’s spending on stimulant medications, such as the amphetamine drugs Ritalin and Adderall, reportedly reached US$39 million in 2010 alone, up from US$7.5 million in 2001 – a jump of more than 500 per cent. Medical officers were writing 32,000 prescriptions for Ritalin and Adderall for active-duty servicemembers every year, up from only 3,000 five years earlier. It remains unclear whether these prescriptions were to counter attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or fatigue, but, as psychiatrist Richard A. Friedman notes, “short of an unlikely epidemic of that disorder among our soldiers, the military almost certainly uses the stimulants to help fatigued and sleep-deprived troops stay alert and awake.”

Meanwhile, US Air Force researchers continued to insist that pilot use of amphetamines enhanced their fighting capacity while decreasing accidents. Dr John Caldwell, writing in Air & Space Power Journal, defended amphetamine use by arguing that for pilots in the “war on terror”, “around-the-clock operations, rapid time-zone transitions, and uncomfortable sleep environments are common on the battlefield; unfortunately, these conditions prevent personnel from obtaining the eight solid hours of sleep required for optimum day-to-day functioning.”

Amphetamines have been the ultimate military performance enhancing drug ever since World War II. That war was not only the most destructive in human history but also the most pharmacologically enhanced. It was literally sped up by speed, with tens of millions of pills doled out to combatants to keep them fighting more and sleeping less. Despite their shift from being widely accessible to being strictly controlled in later decades, the pills have become the drug of choice for many combatants in the most war-ravaged region of the world and continue to be prescribed by the world’s leading military power.

EXCERPT FROM

Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs is published by Oxford University Press.

Peter Andrea is the John Hay Professor of International Studies. He is the author, co-author, or co-editor of eleven books, including his most recent, Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs (Oxford University Press, 2020), which explores the relationship between warfare and mind altering substances, from ancient times to the present. Andreas has also written for a wide range of scholarly and policy publications. Other writings include congressional testimonies and op-eds in major newspapers, such as The New York Times, Washington Post, and The Guardian.

Peter Andrea is the John Hay Professor of International Studies. He is the author, co-author, or co-editor of eleven books, including his most recent, Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs (Oxford University Press, 2020), which explores the relationship between warfare and mind altering substances, from ancient times to the present. Andreas has also written for a wide range of scholarly and policy publications. Other writings include congressional testimonies and op-eds in major newspapers, such as The New York Times, Washington Post, and The Guardian.

His new book, Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs (Oxford University Press, 2020), explores the relationship between warfare and mind altering substances, from ancient times to the present.

Jan 3, 2020 - In a newly released book, “Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs,” Peter Andreas, a professor of international studies at Brown University, has drawn from an impressive and eclectic mix of sources to give psychoactive and addictive drugs a fuller place in discussions of war.

Search Results

Featured snippet from the we

AFP/File / Josh EdelsonApple has said it will ship one million face shields a week for medical workers

AFP/File / Josh EdelsonApple has said it will ship one million face shields a week for medical workers