Radical Currents in Soviet Philosophy: Lev Vygotsky and Evald Ilyenkov

By Arto Artinian

The Problematic of Soviet Marxism

Soviet Marxism is often understood as a tradition that with the exception of figures like Vladimir Lenin or Leon Trotsky, managed to produce very little of significance for twentieth- century Marxist political thought. It is often seen as a void in the overall trajectory of Marxism, made particularly tragic given its origin in the state that emerged from the first successful anti-capitalist revolution. In such a reading, thinkers Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) and Evald Ilyenkov (1924-1979) in particular, are often portrayed as incredible exceptions to this rule, bright stars1 who stood out from the grim, boring, and intellectually mediocre corpus that is often given the label “Soviet Marxism” (or Soviet philosophy).

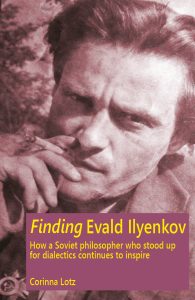

Vygotsky is often presented as the “Mozart of psychology,” a young genius who exploded with creativity before dying young of tuberculosis, having been very likely spared the indignity of perishing in the Great Terror of the late thirties. His contributions are generally positioned in the fields of psychology and literary criticism, rather than political philosophy. Ilyenkov, in turn, is the “oddball” philosopher, the thinker who in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Berlin in 1945, as a young artillery platoon commander, visited Hegel’s grave as his first peacetime activity in liberated Germany.2 Though brilliant, it is suggested he never really fit in the Soviet Marxist tradition, having been sidelined by academic bureaucrats, or by his own eccentricities (overemphasis on the thought of Hegel and Spinoza, for instance).3 And his contributions, though clearly significant in the fields of materialist dialectics, are explicitly connected neither to the domain of Soviet Marxist political thought proper, nor specifically to Soviet politics.

My reading rejects such a characterization of these thinkers, and of Soviet Marxism as a philosophical current itself. On the contrary, I would like to propose that Soviet Marxism reached its height in the work of figures like Vygotsky and Ilyenkov.4 As committed supporters of the unfolding Soviet political project (and I emphasize this point), their presence is unique in the history of twentieth-century Marxist thought, for it represented an attempt at a revolutionary philosophy of praxis from within the Soviet Union, a society-in-formation beyond capitalist forms of social reproduction. Both thinkers understood and approached their struggle toward establishing hegemony within the ideological spaces of Soviet philosophical thought as a struggle of prime importance for the continued social reproduction of revolutionary politics.

But beyond this re-reading of the outlines of Soviet Marxist thought, I will argue that Vygotsky’s and Ilyenkov’s work can be read as an innovative and important addition to contemporary Marxist political thought, where it can contribute to a leftist articulation of effective responses to the functioning of hegemony and ideology within the complex experiences of capitalist everyday life. In doing this, I will propose that Vygotsky articulated a concept of freedom, expressed through human development of a specific type, as a goal of Soviet revolutionary politics. Building on the Marxist tradition, this was an attempt at outlining ways of thinking about freedom, about this final (one could say, strategic) goal of the revolutionary struggle.

To this end, I want to read Vygotsky’s concept of perezhivanie (переживание)5 as a synthesis of the effects of hegemony and ideology as one political phenomenon, an instantiation of the effects of hegemony and ideology in political space (as internalized ideology, internalized consent, hegemony-as-lived-life). It is a description of everyday life structured by specific political struggles, and by the functioning of hegemony and ideology as a unitary political phenomenon. And since it denotes lived experience, it connects directly to questions of social reproduction, although not so much through the lens of sociological (or political economic) analysis as through ontological structures of what I refer to as Becoming and related concepts.

But how is perezhivanie – the lived experience (both collective and individual) of Soviet society – itself shaped? The answer is offered by Evald Ilyenkov’s persistent arguments on the importance of Marxist philosophical thought in shaping the ideal (and what he called “Ideality”), the generalized ways of thinking, or the abstractions that Soviet society would have to develop as it struggled to form its new political community. His interventions on the problematic of the Ideal, or the interiorization of culture, could be read as explicitly political interventions, developing what Vygotsky was able to only implicitly hint at in his concept of perezhivanie. For Ilyenkov, undoing bourgeois hegemony across everyday life, then, presupposes the establishment of hegemony on the level of the Ideal, understood as “the objectifying and disobjectifying of collective human activity” (what he calls culture). Such hegemony6 over what could also be called ideological space (the aggregate of ideological frameworks active in Soviet lived experience at a specific time, say 1964) must be maintained if perezhivanie, the lived general patterns of Soviet everyday life, is to continue a movement toward socialism.

READ THE REST HERE http://sdonline.org/74/5867/