There's No Such Thing as Independent Music in the Age of Coronavirus

IMAGE FROM SHUTTERSTOCK |ILLUSTRATION BY DREW MILLARD

IMAGE FROM SHUTTERSTOCK |ILLUSTRATION BY DREW MILLARD

America’s original gig workers are suddenly out of a job. Banding together as part of a broader labor movement may be the only move musicians have left.

By Emilie Friedlander Apr 23 2020

Ionce spent six months living in the mailroom of VICE's Brooklyn office. I'm actually not kidding: Back before my long-time employer took over the building, the brick-and-cinder-block warehouse on South Second and Kent was home to numerous artist lofts, along with various now-defunct underground music venues with filthy bathrooms and lax smoking policies, like Death by Audio, Glasslands, and 285 Kent.

Living inside that tunnel-like network of interconnected live/work spaces was probably a health hazard: For about $400 a month, I camped out in a stuffy, windowless crawlspace on the upper level of a two-tiered loft bedroom, pretty much exactly corresponding to where the VICE mailroom is right now. But I needed to get out of the spot where I was staying in Bushwick, and a musician friend, who slept on the bottom level, offered to split the rent with me on the room.

It was the first of a number of small acts of kindness I would experience as a broke, 20-something music writer during my long association with that building—all from music people who lived and practiced in that space, who played shows or built crazy-sounding guitar pedals there.

When the music site I was working for got shut down, a bandmate of mine who gigged there got me a job waiting tables up the street. After I started a publication with a friend who was working at a booker down the hall at 285 Kent, the venue's leaseholder let us set up a big plastic table so we could use it as our office. I returned the favor by letting another 285 Kent employee, who actually lived in the venue, pop over to our apartment in the morning to use our shower.

THE AUTHOR'S OLD APARTMENT ON S 1ST STREET, IN WHAT IS NOW THE VICE BUILDING.

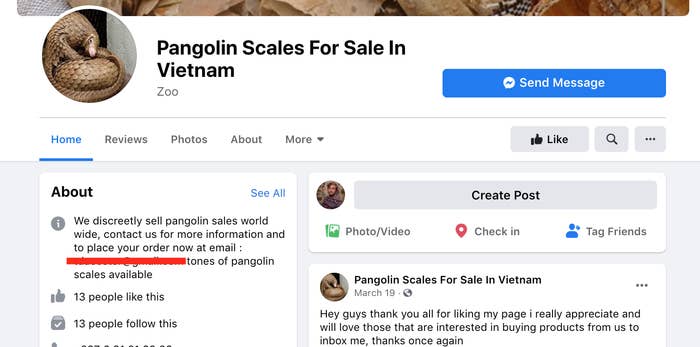

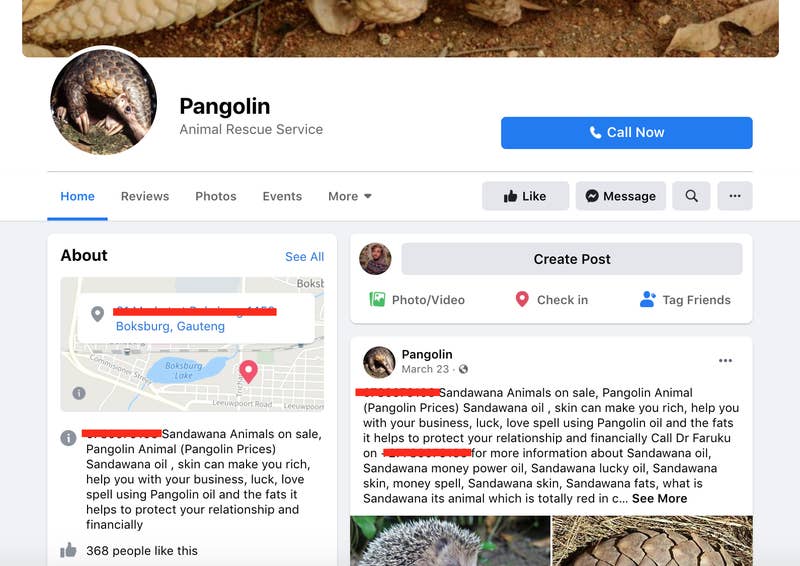

Scenes can be awfully competitive, but if you've ever been a part of one, you probably also have a story about how music provided you with a support system at a time when you desperately needed one. And if you've been paying any attention to the music Internet as the coronavirus crisis grinds live music to a halt, you've likely noticed examples of this sort of mutuality in every corner of the independent music scene, from shuttered venues pivoting to livestreams to raise money for artists with canceled shows, to musicians circulating petitions demanding unemployment benefits, increased streaming royalty rates, and protections against digital copyright infringement. On Friday, March 20, fans spent $4.3 million on Bandcamp after the site declared it was waving its share of music sales for the day—and the NYC Low-Income Artist/Freelancer Relief fund, one of many artist-created fundraisers, has raised over $100,000 so far for BIPOC, Trans/GNC/NB/Queer artists and freelancers whose livelihoods have been cratered by the pandemic.

Independent musicians aren't typically the people who come to mind when you think of the U.S. labor movement. Fans secretly envy them as a class of professional seekers with the luxury of sleeping in on Mondays, traveling the globe, and spending hours just feeling their feelings as the rest of us grind our teeth at a desk. And though their 20th-century counterparts had a proud history of union organizing, we tend to celebrate them less for their civic-mindedness than for the ways they embody a kind of irreverent, outsider approach to life. We love them because they're unashamedly themselves—and, often, for their insistence on quite literally doing it themselves, relying on talent and hustle to build a counter-narrative to an industry that has historically excluded them.

But as the coronavirus obliterates one of the last reliable sources of income that most musicians had left, logging on to music Twitter can feel like watching indie music's conception of itself shatter in slow motion—and something new rising in its place. As writer Liz Pelly has astutely observed, the very notion of "independent music" was already starting to feel pretty hollow in an era where artists are all beholden to streaming services that pay pennies-on-the-dollar per stream. Now, for the first time in our lifetime, and partly because they've been forced to, musicians are collectively voicing the fact that they are not merely exquisite souls, but workers—workers who are now out of a job, and who deserve the same protections that all workers do.

***

Musicians were already in a precarious position before the crisis hit: America's original gig workers, they've been cobbling together a living from touring, music and merch sales, music lessons, and sporadic licensing deals and label advances since long before Silicon Valley repurposed the term to make economic precarity seem desirable.

Like Uber drivers, Instacart workers, and others who subsist primarily on 1099 income, musicians don't typically qualify for unemployment in most states; employer-sponsored health coverage and paid sick leave are for the most part off the table, which is frightening when you consider how little money many of them are making in the first place. In 2018, a survey by the Music Industry Research Association found that the median income for musicians in the U.S. was between $20,000 and $25,000 per year, with 61 percent reporting that the income they made from music was not enough to meet their living expenses.

"Anyone fully dependent on music or mostly dependent on music was completely fucked by this," said Joey La Neve DeFrancesco, a Rhode Island-based musician and organizer probably best known as the guitarist for the punk band Downtown Boys. "You were increasingly only making money via performing, and all of a sudden that one revenue stream is completely and utterly destroyed."

Like most independent musicians in the streaming era, DeFrancesco says the majority of his income comes from touring and playing festivals; in 2019, he estimates, gigging comprised 90 percent. Not surprisingly, once he noticed venue performances and festivals being canceled across the country last month, he found himself logging onto the website for the Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training, trying to file for unemployment.

"I spent hours and hours trying to fill out this application, getting on the phone with them, getting weird error messages," he says. "Of course, to finally get to the point where it was like, 'Oh, I still can't apply for unemployment with 1099 income.'"

As the Senate deliberated over a historic $2.2 trillion stimulus package in Washington, he started emailing with other musicians. The group came to a spur-of-the-moment decision to launch an open letter to Congress, demanding an expansion of unemployment and other benefits for musicians, crew members, and other independent contractors. Before long, hundreds of musicians were signing the petition every day; after legacy indie artists like Bikini Kill, Fugazi, and Neutral Milk Hotel jumped on, the music press picked up the story.

Fortunately for millions of people in this country, when the bill passed, it included a provision expanding some unemployment benefits to freelancers and other self-employed people, along with benefits like paid sick leave and paid family leave. While it's hard to say how much of an impact the letter made (DeFrancesco says he did receive a letter from Nancy Pelosi's office, acknowledging receipt and expressing their appreciation), it was a striking show of solidarity from a group of artists who, on the whole, aren't exactly accustomed to openly identifying as part of the working class.

"This group was a group of workers who were not yet organized but who were angry, who were out of work, and suddenly had time," said DeFrancesco, who cut his teeth as an organizer while working in the hotel business. On the day that we spoke, he and a group of Rhode Island-based musicians had launched a similar open letter demanding that the state government distribute federal funding for artists and other gig economy workers "immediately and without undue burden on applicants," along with implementing a rent freeze and the creation of an artist relief fund. (So far, he says, the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts has already begun making emergency grant funding available).

***

As the live music shutdown magnifies the damage wrought by a decade-long decline in album sales and a streaming economy that largely benefits artists who are already very successful to begin with (or who happen to land a coveted playlist placement), other musicians have been focusing on putting pressure on platforms to demand a fairer payout.

When a show she was slated to play opening for Anti-Flag in mid-March got canceled, Boston-based singer-songwriter Evan Greer wasn't necessarily fretting over the lost work. She had a day job as the deputy director of Fight for the Future, a digital rights organization, but she started worrying about how her friends in the queer music community were going to get by. "All of the income they had planned for the next three months just evaporated in a week," she remembers.

When she thought back to the last streaming royalties check she'd received from her label—the amount, she said, was "totally laughable"—she started to get angry. "If we're building a music industry where you can only make a living if you either create music that's designed to game a specific company's algorithm, rather than the music that you want to make—or you tour 300 days a year—then we're creating a music industry that leaves a lot of people out," she said.

On a whim, she logged onto the Action Network and drafted a petition demanding that Spotify immediately—and permanently—triple the amount they pay artists per stream, in addition to donating $500,000 to music charity Sweet Relief. (In 2019, according to one analysis, the company paid artists an average of $0.00318 per stream, which means that in order to make $3180, your song would need to be streamed a million times). The petition has 2001 signatures and counting.

On March 25, about a week after the petition started circulating, Spotify went wide with an announcement: The company was unveiling a new project called Spotify COVID-19 Music Relief, donating funds to five music-related charities and matching outside donations dollar-for-dollar, for a total contribution of $10 million. It also unveiled plans to introduce a controversial new feature that would enable musicians to raise money directly from their artist profile pages, by linking out to a fundraising page of their choice. (When it debuted this week alongside a charitable partnership with CashApp, musicians compared the feature to a "tip jar," with one writer describing it as a "tacit admission that artists are not being paid enough.")

Greer doesn't know what effect, if any, the petition had on Spotify's internal calculus, but she's glad to have contributed to the chorus of voices demanding that Spotify do something in response to the crisis, even if its focus on charitable donations felt a bit like an attempt to paper over the problem. "This is kind of the version of the boss sending everyone a nice fruit basket instead of just like paying you," she said. It didn't help that just a few weeks before, Spotify announced it was teaming with Amazon, Google, and Pandora to appeal a U.S. Copyright Royalty Board ruling mandating that streaming services increase its royalty payments to songwriters by 44%.

That artists aren't simply pulling their catalogs en masse speaks to a truth they know as well as their digital overlords do: Musicians aren't really in a position to opt out of a system that reduces their songs (not to mention the behavior and moods of the people who stream them) to widgets in an ad-revenue machine. As record stores shutter and a formerly robust music journalism scrapes by as a corpse of its former self, listeners looking to discover new music will continue turning to platforms that are designed for that express purpose, especially when that means they can consume nearly every album in the world for less than ten bucks a month. In an industry where attention is everything, there's no fate worse than becoming invisible.

***

Like many gig-economy workers, today's musicians are beholden to the cold logic of invisible algorithms that determine when they will get paid and how much, forgoing the stability that comes with traditional employment for the freedom that comes with being able to make one's own hours and decide how much one will work.

Whether they agree to this arrangement because they find it appealing, or because they feel they have no other choice, they're participants in a system that diminishes the cost of their labor while benefiting the wealthy few. Lest we forget, streaming is an extraordinarily lucrative business: According to the RIAA, last year, the U.S. record industry generated $8.8 billion from streaming alone, more than the total revenue of the entire recorded-music sector in 2017. And as your average independent musician struggles to pay rent, major labels Sony Music Group, Warner Music Group, and Universal Music Group, also known as the "big three," are doing pretty well; in Q4 of 2019, they jointly generated nearly $1 million an hour in streaming, according to a Music Business News analysis of the companies' quarterly financial reports.

Technically speaking, though, most musicians don't actually work for these services; unlike the Instacart shoppers who went on strike earlier this month to demand hazard pay, sick leave, and hand sanitizer, they don't even boast a common employer to rise up against. Instead, they're disconnected actors in an attention economy that operates according to a survival-of-the-fittest logic, forced to compete with each other for each fraction of a penny they receive.

Partly owing to this uncomfortable marriage between counterculture and hustle culture, Mat Dryhurst, an artist and researcher who works as a lecturer at the New York University's Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, has spent the past few years arguing that the term "independent music" is no longer fit for purpose. For one thing, the cultural context it describes—that of an alternative musical economy arising out of the indie rock label system of the 1980s and 1990s—no longer applies in a world where underground musicians and pop stars are all competing for attention on the same publicly traded platforms.

Over the phone, Dryhurst was quick to credit that spirit of "irreverent individualism" for powering some of the greatest counter-cultural moments of the 20th century (think: the hippie movement, punk rock and hip-hop and early DJ culture, 1990s "do-it-yourself"). But in the era of platform capitalism, he fears, it may simply have the effect of dividing us.

In an April 2019 editorial for the Guardian, Dryhurst suggested the term "interdependence" as a more appropriate descriptor for what a genuine 21st-century alternative might look like. "[When] people think romantically about the independent music industry, most of the things that they actually like about it can be described as the interdependent components of it," he told me. "Even though the singer is the most prominent person in the press shot, they're going out there in the world, and as a result of them getting paid, the band members get paid, and then the label gets paid, and then the person who made the artwork gets paid, and then the mixing engineer gets paid. That infrastructure, to me, presents an interesting hard contrast [with] the general march toward isolation."

It's tempting to say that the coronavirus will be the thing that pushes music out of the era of independence and into a more interdependent one—though there were signs of this even before the virus ground the entire industry to a halt.

DeFrancesco and Greer are part of an informal network of musicians from across the country who have staged a handful of organizing campaigns over the past few years. (DeFrancesco estimates the group of participating musicians to be about a thousand strong.) In 2017, they convinced SXSW to remove a clause in its artist contract saying that it would work with ICE to deport foreign artists who violated the terms of the agreement. In 2019, they got 40 major music festivals to agree to a ban on facial recognition technology. They've since staged a number of digital direct actions focused on Amazon's ties to U.S. immigration enforcement, working under the banner No Music for Ice.

You could see a similar impulse at work during the first few months of this year, when, for a brief moment, it felt like artists from all over the musical spectrum—from Soccer Mommy and Vampire Weekend to Public Enemy and Cardi B—were collectively leveraging their influence in support of former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, culminating in an eclectic, oddly scene-agnostic traveling music festival the campaign dubbed "BerniePalooza."

The Vermont senator is out of the race and musicians' hope for a self-proclaimed "arts president" has been dashed, but it's hard to imagine musicians losing that taste for collective action any time soon. DeFrancesco sees increased public arts funding as something high on his list of priorities as an organizer, along with musicians lending their support to other causes that support all members of the working class during this time of crisis, such a rent freeze and Medicare for All.

But along with demanding more from our government and large music companies, DeFrancesco, Greer, and Dryhurst expect to see musicians using the crisis as an opportunity to experiment with alternative forms of economic support, from homegrown wealth-sharing initiatives to novel platforms that offer a glimpse of what an independent world without Big Streaming might look like.

In March, musicians Zola Jesus and Devon Welsh unveiled Koir TV, a site that aims to streamline the process for musicians looking to collect revenue while they livestream performances from home. Ampled, a project incubated at the New Museum, is a Patreon-like, artist and worker-owned cooperative that enables musicians to share original audio and other content with fans for a monthly donation. "In today's platform economy, musicians are digital sharecroppers," co-founder Austin Robey told me in an email. "They generate all the value for platforms, yet capture none of it. Our mission is to make music more equitable for artists, and to provide an alternative to extractive investor-owned platforms."

Relying on the goodwill of one's community is no substitute for fair wages and a public safety net, but at times like these, that mutual support system—our fundamental interdependence—may be the only thing we have left. After New York City enacted a moratorium on public gatherings, workers at venues and booking companies all over the city, including the company I co-founded, organized GoFundMe campaigns to offset some of the financial consequences they were facing as a result of their schedule of shows being interrupted.

Watching the names of people I hadn't seen in almost a decade pop up on the GoFundMe dashboard—people I used to party with at 285 Kent, the sort of life-long music lovers I know still buy records as often as they can—I felt a sense of community I hadn't known I had been missing. Somehow, it was the tersest comment that finally caused me to cry: "Thanks for all the list spots."

By Emilie Friedlander Apr 23 2020

Ionce spent six months living in the mailroom of VICE's Brooklyn office. I'm actually not kidding: Back before my long-time employer took over the building, the brick-and-cinder-block warehouse on South Second and Kent was home to numerous artist lofts, along with various now-defunct underground music venues with filthy bathrooms and lax smoking policies, like Death by Audio, Glasslands, and 285 Kent.

Living inside that tunnel-like network of interconnected live/work spaces was probably a health hazard: For about $400 a month, I camped out in a stuffy, windowless crawlspace on the upper level of a two-tiered loft bedroom, pretty much exactly corresponding to where the VICE mailroom is right now. But I needed to get out of the spot where I was staying in Bushwick, and a musician friend, who slept on the bottom level, offered to split the rent with me on the room.

It was the first of a number of small acts of kindness I would experience as a broke, 20-something music writer during my long association with that building—all from music people who lived and practiced in that space, who played shows or built crazy-sounding guitar pedals there.

When the music site I was working for got shut down, a bandmate of mine who gigged there got me a job waiting tables up the street. After I started a publication with a friend who was working at a booker down the hall at 285 Kent, the venue's leaseholder let us set up a big plastic table so we could use it as our office. I returned the favor by letting another 285 Kent employee, who actually lived in the venue, pop over to our apartment in the morning to use our shower.

THE AUTHOR'S OLD APARTMENT ON S 1ST STREET, IN WHAT IS NOW THE VICE BUILDING.

Scenes can be awfully competitive, but if you've ever been a part of one, you probably also have a story about how music provided you with a support system at a time when you desperately needed one. And if you've been paying any attention to the music Internet as the coronavirus crisis grinds live music to a halt, you've likely noticed examples of this sort of mutuality in every corner of the independent music scene, from shuttered venues pivoting to livestreams to raise money for artists with canceled shows, to musicians circulating petitions demanding unemployment benefits, increased streaming royalty rates, and protections against digital copyright infringement. On Friday, March 20, fans spent $4.3 million on Bandcamp after the site declared it was waving its share of music sales for the day—and the NYC Low-Income Artist/Freelancer Relief fund, one of many artist-created fundraisers, has raised over $100,000 so far for BIPOC, Trans/GNC/NB/Queer artists and freelancers whose livelihoods have been cratered by the pandemic.

Independent musicians aren't typically the people who come to mind when you think of the U.S. labor movement. Fans secretly envy them as a class of professional seekers with the luxury of sleeping in on Mondays, traveling the globe, and spending hours just feeling their feelings as the rest of us grind our teeth at a desk. And though their 20th-century counterparts had a proud history of union organizing, we tend to celebrate them less for their civic-mindedness than for the ways they embody a kind of irreverent, outsider approach to life. We love them because they're unashamedly themselves—and, often, for their insistence on quite literally doing it themselves, relying on talent and hustle to build a counter-narrative to an industry that has historically excluded them.

But as the coronavirus obliterates one of the last reliable sources of income that most musicians had left, logging on to music Twitter can feel like watching indie music's conception of itself shatter in slow motion—and something new rising in its place. As writer Liz Pelly has astutely observed, the very notion of "independent music" was already starting to feel pretty hollow in an era where artists are all beholden to streaming services that pay pennies-on-the-dollar per stream. Now, for the first time in our lifetime, and partly because they've been forced to, musicians are collectively voicing the fact that they are not merely exquisite souls, but workers—workers who are now out of a job, and who deserve the same protections that all workers do.

***

Musicians were already in a precarious position before the crisis hit: America's original gig workers, they've been cobbling together a living from touring, music and merch sales, music lessons, and sporadic licensing deals and label advances since long before Silicon Valley repurposed the term to make economic precarity seem desirable.

Like Uber drivers, Instacart workers, and others who subsist primarily on 1099 income, musicians don't typically qualify for unemployment in most states; employer-sponsored health coverage and paid sick leave are for the most part off the table, which is frightening when you consider how little money many of them are making in the first place. In 2018, a survey by the Music Industry Research Association found that the median income for musicians in the U.S. was between $20,000 and $25,000 per year, with 61 percent reporting that the income they made from music was not enough to meet their living expenses.

"Anyone fully dependent on music or mostly dependent on music was completely fucked by this," said Joey La Neve DeFrancesco, a Rhode Island-based musician and organizer probably best known as the guitarist for the punk band Downtown Boys. "You were increasingly only making money via performing, and all of a sudden that one revenue stream is completely and utterly destroyed."

Like most independent musicians in the streaming era, DeFrancesco says the majority of his income comes from touring and playing festivals; in 2019, he estimates, gigging comprised 90 percent. Not surprisingly, once he noticed venue performances and festivals being canceled across the country last month, he found himself logging onto the website for the Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training, trying to file for unemployment.

"I spent hours and hours trying to fill out this application, getting on the phone with them, getting weird error messages," he says. "Of course, to finally get to the point where it was like, 'Oh, I still can't apply for unemployment with 1099 income.'"

As the Senate deliberated over a historic $2.2 trillion stimulus package in Washington, he started emailing with other musicians. The group came to a spur-of-the-moment decision to launch an open letter to Congress, demanding an expansion of unemployment and other benefits for musicians, crew members, and other independent contractors. Before long, hundreds of musicians were signing the petition every day; after legacy indie artists like Bikini Kill, Fugazi, and Neutral Milk Hotel jumped on, the music press picked up the story.

Fortunately for millions of people in this country, when the bill passed, it included a provision expanding some unemployment benefits to freelancers and other self-employed people, along with benefits like paid sick leave and paid family leave. While it's hard to say how much of an impact the letter made (DeFrancesco says he did receive a letter from Nancy Pelosi's office, acknowledging receipt and expressing their appreciation), it was a striking show of solidarity from a group of artists who, on the whole, aren't exactly accustomed to openly identifying as part of the working class.

"This group was a group of workers who were not yet organized but who were angry, who were out of work, and suddenly had time," said DeFrancesco, who cut his teeth as an organizer while working in the hotel business. On the day that we spoke, he and a group of Rhode Island-based musicians had launched a similar open letter demanding that the state government distribute federal funding for artists and other gig economy workers "immediately and without undue burden on applicants," along with implementing a rent freeze and the creation of an artist relief fund. (So far, he says, the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts has already begun making emergency grant funding available).

***

As the live music shutdown magnifies the damage wrought by a decade-long decline in album sales and a streaming economy that largely benefits artists who are already very successful to begin with (or who happen to land a coveted playlist placement), other musicians have been focusing on putting pressure on platforms to demand a fairer payout.

When a show she was slated to play opening for Anti-Flag in mid-March got canceled, Boston-based singer-songwriter Evan Greer wasn't necessarily fretting over the lost work. She had a day job as the deputy director of Fight for the Future, a digital rights organization, but she started worrying about how her friends in the queer music community were going to get by. "All of the income they had planned for the next three months just evaporated in a week," she remembers.

When she thought back to the last streaming royalties check she'd received from her label—the amount, she said, was "totally laughable"—she started to get angry. "If we're building a music industry where you can only make a living if you either create music that's designed to game a specific company's algorithm, rather than the music that you want to make—or you tour 300 days a year—then we're creating a music industry that leaves a lot of people out," she said.

On a whim, she logged onto the Action Network and drafted a petition demanding that Spotify immediately—and permanently—triple the amount they pay artists per stream, in addition to donating $500,000 to music charity Sweet Relief. (In 2019, according to one analysis, the company paid artists an average of $0.00318 per stream, which means that in order to make $3180, your song would need to be streamed a million times). The petition has 2001 signatures and counting.

On March 25, about a week after the petition started circulating, Spotify went wide with an announcement: The company was unveiling a new project called Spotify COVID-19 Music Relief, donating funds to five music-related charities and matching outside donations dollar-for-dollar, for a total contribution of $10 million. It also unveiled plans to introduce a controversial new feature that would enable musicians to raise money directly from their artist profile pages, by linking out to a fundraising page of their choice. (When it debuted this week alongside a charitable partnership with CashApp, musicians compared the feature to a "tip jar," with one writer describing it as a "tacit admission that artists are not being paid enough.")

Greer doesn't know what effect, if any, the petition had on Spotify's internal calculus, but she's glad to have contributed to the chorus of voices demanding that Spotify do something in response to the crisis, even if its focus on charitable donations felt a bit like an attempt to paper over the problem. "This is kind of the version of the boss sending everyone a nice fruit basket instead of just like paying you," she said. It didn't help that just a few weeks before, Spotify announced it was teaming with Amazon, Google, and Pandora to appeal a U.S. Copyright Royalty Board ruling mandating that streaming services increase its royalty payments to songwriters by 44%.

That artists aren't simply pulling their catalogs en masse speaks to a truth they know as well as their digital overlords do: Musicians aren't really in a position to opt out of a system that reduces their songs (not to mention the behavior and moods of the people who stream them) to widgets in an ad-revenue machine. As record stores shutter and a formerly robust music journalism scrapes by as a corpse of its former self, listeners looking to discover new music will continue turning to platforms that are designed for that express purpose, especially when that means they can consume nearly every album in the world for less than ten bucks a month. In an industry where attention is everything, there's no fate worse than becoming invisible.

***

Like many gig-economy workers, today's musicians are beholden to the cold logic of invisible algorithms that determine when they will get paid and how much, forgoing the stability that comes with traditional employment for the freedom that comes with being able to make one's own hours and decide how much one will work.

Whether they agree to this arrangement because they find it appealing, or because they feel they have no other choice, they're participants in a system that diminishes the cost of their labor while benefiting the wealthy few. Lest we forget, streaming is an extraordinarily lucrative business: According to the RIAA, last year, the U.S. record industry generated $8.8 billion from streaming alone, more than the total revenue of the entire recorded-music sector in 2017. And as your average independent musician struggles to pay rent, major labels Sony Music Group, Warner Music Group, and Universal Music Group, also known as the "big three," are doing pretty well; in Q4 of 2019, they jointly generated nearly $1 million an hour in streaming, according to a Music Business News analysis of the companies' quarterly financial reports.

Technically speaking, though, most musicians don't actually work for these services; unlike the Instacart shoppers who went on strike earlier this month to demand hazard pay, sick leave, and hand sanitizer, they don't even boast a common employer to rise up against. Instead, they're disconnected actors in an attention economy that operates according to a survival-of-the-fittest logic, forced to compete with each other for each fraction of a penny they receive.

Partly owing to this uncomfortable marriage between counterculture and hustle culture, Mat Dryhurst, an artist and researcher who works as a lecturer at the New York University's Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, has spent the past few years arguing that the term "independent music" is no longer fit for purpose. For one thing, the cultural context it describes—that of an alternative musical economy arising out of the indie rock label system of the 1980s and 1990s—no longer applies in a world where underground musicians and pop stars are all competing for attention on the same publicly traded platforms.

Over the phone, Dryhurst was quick to credit that spirit of "irreverent individualism" for powering some of the greatest counter-cultural moments of the 20th century (think: the hippie movement, punk rock and hip-hop and early DJ culture, 1990s "do-it-yourself"). But in the era of platform capitalism, he fears, it may simply have the effect of dividing us.

In an April 2019 editorial for the Guardian, Dryhurst suggested the term "interdependence" as a more appropriate descriptor for what a genuine 21st-century alternative might look like. "[When] people think romantically about the independent music industry, most of the things that they actually like about it can be described as the interdependent components of it," he told me. "Even though the singer is the most prominent person in the press shot, they're going out there in the world, and as a result of them getting paid, the band members get paid, and then the label gets paid, and then the person who made the artwork gets paid, and then the mixing engineer gets paid. That infrastructure, to me, presents an interesting hard contrast [with] the general march toward isolation."

It's tempting to say that the coronavirus will be the thing that pushes music out of the era of independence and into a more interdependent one—though there were signs of this even before the virus ground the entire industry to a halt.

DeFrancesco and Greer are part of an informal network of musicians from across the country who have staged a handful of organizing campaigns over the past few years. (DeFrancesco estimates the group of participating musicians to be about a thousand strong.) In 2017, they convinced SXSW to remove a clause in its artist contract saying that it would work with ICE to deport foreign artists who violated the terms of the agreement. In 2019, they got 40 major music festivals to agree to a ban on facial recognition technology. They've since staged a number of digital direct actions focused on Amazon's ties to U.S. immigration enforcement, working under the banner No Music for Ice.

You could see a similar impulse at work during the first few months of this year, when, for a brief moment, it felt like artists from all over the musical spectrum—from Soccer Mommy and Vampire Weekend to Public Enemy and Cardi B—were collectively leveraging their influence in support of former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, culminating in an eclectic, oddly scene-agnostic traveling music festival the campaign dubbed "BerniePalooza."

The Vermont senator is out of the race and musicians' hope for a self-proclaimed "arts president" has been dashed, but it's hard to imagine musicians losing that taste for collective action any time soon. DeFrancesco sees increased public arts funding as something high on his list of priorities as an organizer, along with musicians lending their support to other causes that support all members of the working class during this time of crisis, such a rent freeze and Medicare for All.

But along with demanding more from our government and large music companies, DeFrancesco, Greer, and Dryhurst expect to see musicians using the crisis as an opportunity to experiment with alternative forms of economic support, from homegrown wealth-sharing initiatives to novel platforms that offer a glimpse of what an independent world without Big Streaming might look like.

In March, musicians Zola Jesus and Devon Welsh unveiled Koir TV, a site that aims to streamline the process for musicians looking to collect revenue while they livestream performances from home. Ampled, a project incubated at the New Museum, is a Patreon-like, artist and worker-owned cooperative that enables musicians to share original audio and other content with fans for a monthly donation. "In today's platform economy, musicians are digital sharecroppers," co-founder Austin Robey told me in an email. "They generate all the value for platforms, yet capture none of it. Our mission is to make music more equitable for artists, and to provide an alternative to extractive investor-owned platforms."

Relying on the goodwill of one's community is no substitute for fair wages and a public safety net, but at times like these, that mutual support system—our fundamental interdependence—may be the only thing we have left. After New York City enacted a moratorium on public gatherings, workers at venues and booking companies all over the city, including the company I co-founded, organized GoFundMe campaigns to offset some of the financial consequences they were facing as a result of their schedule of shows being interrupted.

Watching the names of people I hadn't seen in almost a decade pop up on the GoFundMe dashboard—people I used to party with at 285 Kent, the sort of life-long music lovers I know still buy records as often as they can—I felt a sense of community I hadn't known I had been missing. Somehow, it was the tersest comment that finally caused me to cry: "Thanks for all the list spots."