Andrés Manuel López Obrador has been forced to apologize after insinuating that doctors were greedy.

Karla ZabludovskyBuzzFeed News Reporter

Reporting From Mexico City May 11, 2020,

Henry Romero / Reuters

MEXICO CITY — As COVID-19 cases climb in Mexico, a row has broken out between the president and medical groups after he accused some doctors of only being in it for the money.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador has been criticized by former health ministers for botching the country’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. At a press conference on Friday, López Obrador turned on his critics, saying that under previous administrations, the first question doctors would ask their patients was not about their condition, but how much money they had. He did not specify how he knew this, who the doctors he was talking about were, or whether they worked in the public or private sector.

The accusation prompted at least 23 colleges and associations across the country to demand a public apology, calling it “irresponsible” and “shameful.”

“This is offensive to the entire medical guild,” the Mexican Association of General Surgery said in a written statement. “It is not a moment to criticize, disqualify or censure” healthcare.

For some, López Obrador’s claim was no surprise, as he often rails against the “neoliberal” governments that came before him. He uses his daily press conferences to attack critics and the media, and has consistently underplayed the coronavirus health crisis — he was still out hugging supporters and touring the country well after his own experts advised people to stay home.

After coming under fire, López Obrador tried to walk back his accusation at Monday's press conference, saying that if doctors took his statement to mean he thought they were looking to enrich themselves, “I offer them an apology.” He then went on to say that the socialist revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara had been a doctor.

Protests over the lack of protective gear have broken out in several states as dozens of health workers have contracted COVID-19. Shortages hobbled the healthcare system even before the pandemic hit, after López Obrador ordered steep budget cuts that delayed surgeries and led to layoffs. Last year, Germán Martínez, the head of the social security institute, which provides healthcare access to more than 12 million Mexicans, resigned after calling the cuts “inhumane.”

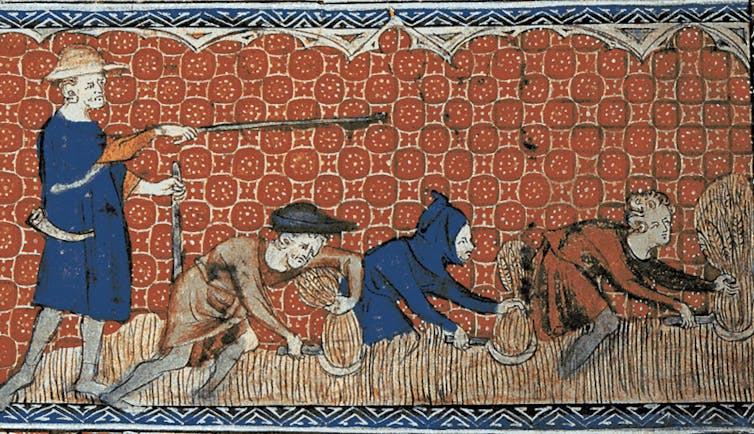

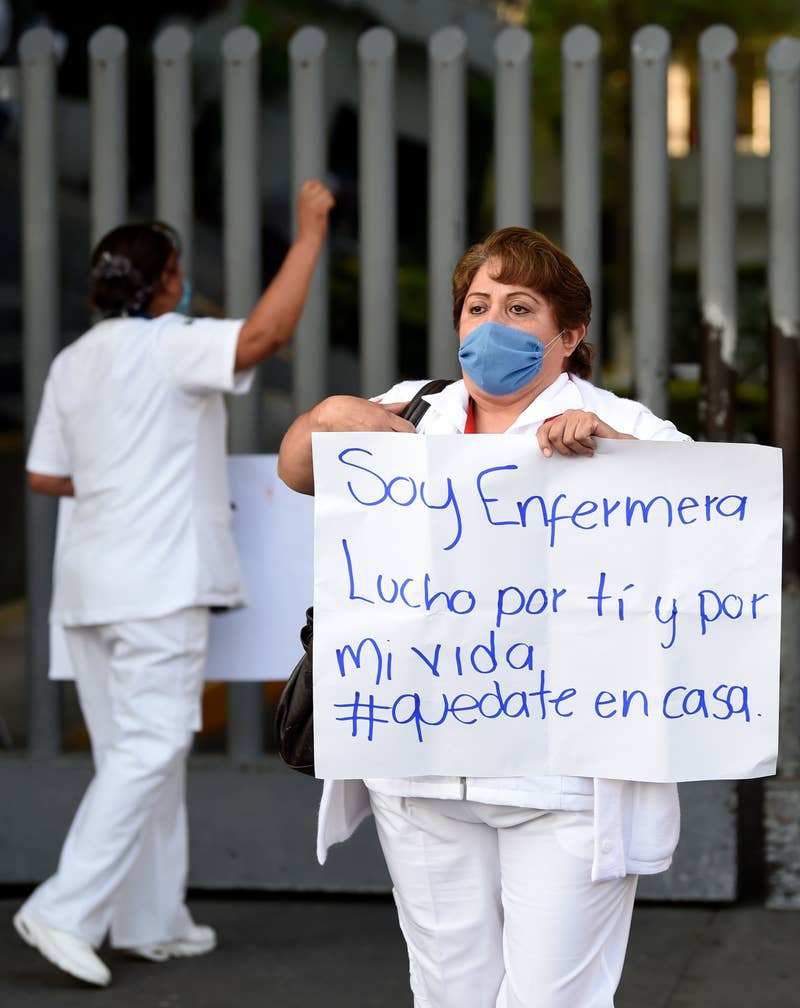

Alfredo Estrella / Getty Images

A health worker holds a sign reading, "I am a nurse. I fight for you and for my life #stayathome," during a protest in Mexico City on April 13.

Dozens of health workers have been subjected to verbal and physical attacks, including a nurse who was doused with bleach by a stranger as she walked home from work and an emergency room doctor who was detained by police as he tried to drive into his neighborhood. In the State of Mexico, people broke into a public hospital and punched medical personnel they accused of injecting patients with deadly solutions to kill them.

“No other country in the world has seen their medical staff as abandoned as we’ve been here,” said Francisco Moreno, an infectious disease expert at Mexico City’s ABC Hospital, a private hospital. “The prime example of that has been given by the president.”

López Obrador’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Most unsettling for many in the medical community here is the sense that they are in the dark about the magnitude of the crisis in Mexico. According to health officials, there are 35,022 confirmed cases and 3,465 deaths, but complaints of widespread underreporting have cast doubt about these numbers. With about 1,000 tests per 1 million people, Mexico has one of the lowest testing rates in the world, according to the private research firm Statista.

Officials maintain that about 75% of hospital beds with access to a ventilator nationwide, and 38% in Mexico City, remain available, but doctors are doubtful. In Mexico City, virtually all of these beds in private hospitals are in use, according to Moreno.

Last week, reports by El País, the Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times pointed to a significantly higher death toll in Mexico than the government has reported.

José Narro Robles, who served as health minister under the previous administration, has called into question Mexico’s official COVID-19 count, warning that many cases are being reported as influenza or atypical pneumonia.

When asked about these accusations on Friday, López Obrador waved them off as political wrangling and said that prior to his government, corruption had reigned in the healthcare system.

But López Obrador is facing reports of corruption within his own government. A company owned by León Manuel Bartlett, the son of one of his allies, has come under investigation for selling overpriced ventilators to the state, at the cost of $65,000 each — rather than the $20,000 they cost before the crisis broke out — according to Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad, a civil anti-corruption group.

Karla Zabludovsky is the Mexico bureau chief and Latin America correspondent for BuzzFeed News and is based in Mexico City.