“As a nurse or a doctor, at least you're getting paid a decent amount of money to risk your life," one hospital clerical worker earning $15 an hour told BuzzFeed News.

Emmanuel Felton BuzzFeed News Reporter

Posted on May 13, 2020

Chip Somodevilla / Getty Images

An X-ray technician and medical assistant disinfects an examination room in between testing patients for the novel coronavirus on April 15 in Woodbridge, Virginia.

As the novel coronavirus began spreading in the United States in February and March, a clerical worker at the University Medical Center New Orleans was spending her shifts going in and out of patients’ rooms, collecting insurance information

It didn’t take long for her to get sick.

In early March, as coronavirus cases began exploding in the city after Mardi Gras, she came down with chills, body aches, and shortness of breath. When she finally got a test three weeks later, it came back negative for COVID-19. But there are concerns about some tests returning false negatives, and she doesn’t trust that hers was performed correctly. Nearly two months and several hospital visits later, she said she has been stuck at home and hasn’t fully recovered.

When she was risking infection at work, the woman, who asked not to be identified as she feared reprisal from her employer, was earning just $15 an hour. As she is not a full-time employee, unlike the clinical staff at her hospital, she doesn’t get paid sick time or vacation days. She also doesn’t get health insurance. The only reason she isn’t saddled with thousands of dollars of medical debt is that she made so little working at the hospital that she qualified for the state’s Medicaid program, which was recently expanded to include adults earning low incomes like her.

“As a nurse or a doctor, at least you're getting paid a decent amount of money to risk your life,” the woman told BuzzFeed News. “It pisses me off because they're not looking out for the most vulnerable people who don't have benefits.”

She added: “They want people to risk their lives and get paid little to nothing. It's not worth it. It's just not.”

The New Orleans staffer is a part of the healthcare industry’s often overlooked class of hourly workers — home health aides, records clerks, nursing assistants, and hospital janitors — who are risking their lives during the coronavirus pandemic with little or no safety net.

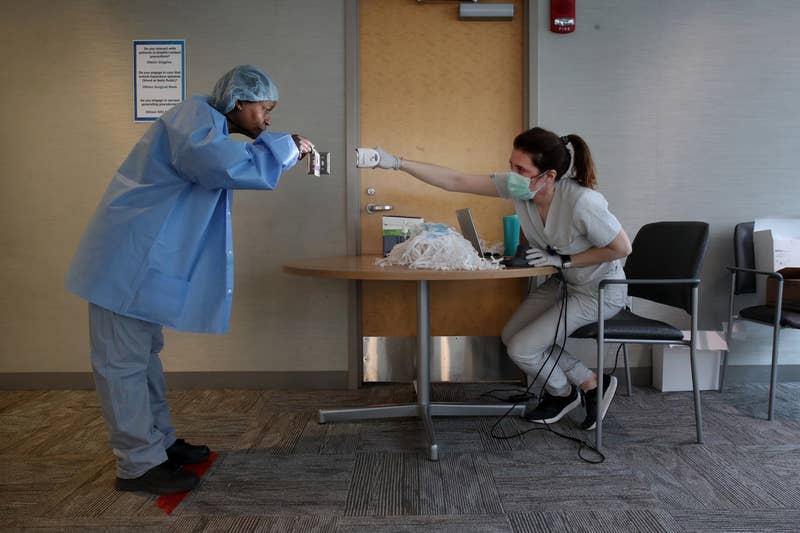

Boston Globe / Getty Images

Boston Globe / Getty Images

A personal care assistant leaves home in Massachusetts to care for an elderly woman in Watertown on March 26.

Women of color, like the New Orleans staffer, are overrepresented in the industry's lowest-paid rungs. Researchers found that nearly half of black and Latina women healthcare workers earned less than $15 an hour.

“It's a vast, unseen, low-paid workforce,” said Atheendar Venkataramani, a professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the study’s authors. “There's a tremendous amount of wage inequality in healthcare, and typically these low-wage jobs are held by women and underrepresented minorities.”

Venkataramani became interested in the topic several years ago when he was a primary care doctor in Massachusetts. One of his patients was a home health aide who earned little more than the state minimum wage and only sporadically had health insurance. “It seemed incredibly unfair to me that this person, who is at some level a colleague of mine — we're both in the same industry, but to provide her medical care required dealing with a number of challenges presented by her socioeconomic circumstances,” he said. “It was kind of an eye-opening experience for me. It didn't seem particularly fair.”

Hospitals employ low-paid workers in a range of different jobs. Some are performing administrative work or answering phones, while others are cooking meals or cleaning rooms or working as security guards. All face a risk of infection during the coronavirus pandemic. Just last week, the New York Times reported on three hospital administrative staffers who were part of the “invisible army” in charge of handing out personal protective equipment at Queens’ Elmhurst Hospital Center and replenishing supplies. All three contracted the coronavirus and died.

Sepia Coleman, a healthcare worker in Memphis, has spent 30 years working in the industry. She still works two jobs, one as a home health aide at $10.50 an hour, and another on the night shift at a nursing home at $12 an hour.

"We are in the room when no one else is,” said Coleman. “Doctors and nurses only come in to do things like administer medications; we're there all the time. We have to make sure their vitals are OK. We have to watch them to see if they have any change in behavior or color. We are beyond essential. We are the main component of the healthcare system, but we get no credit for that.”

Neither of her jobs offers paid sick leave; if she contracts the virus, she has no idea how she will pay her bills.

"I work with sick patients. That's what I do. Why not give us sick pay?” Coleman told BuzzFeed News. “I'm disgusted and I'm really hurt. I knew the healthcare system was broken, but this pandemic has shown their true colors with all the greed and neglect — not just of residents, but of us, too. It's just like they don't care.”

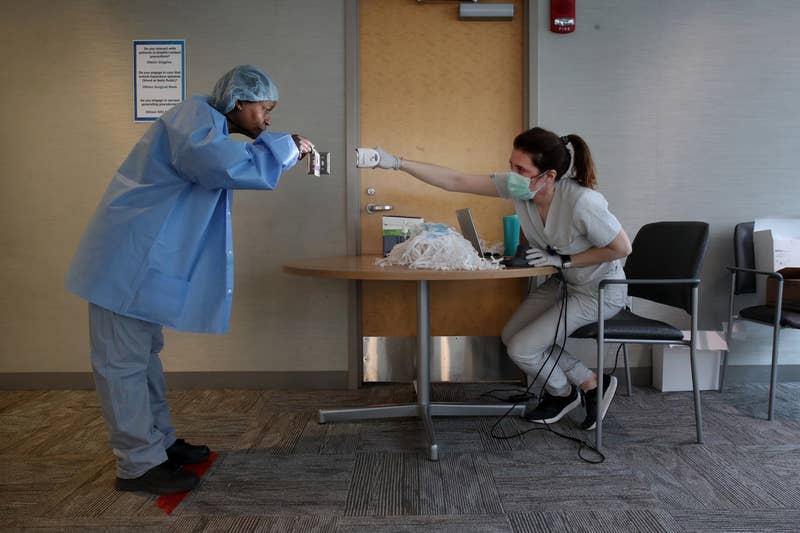

Boston Globe / Getty Images

A medical assistant scans a staff member's identification badge in a personal protective equipment distribution area at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston on March 25.

Joyce Barnes of Richmond, Virginia, has also worked in healthcare for over 30 years. Even in the best of times, she said, working as a home healthcare aide is tough, grueling work. “You don't get any raises. You don't get any vacation time. You don't get paid sick time. You have to work all the time,” she said.

“I've always felt like we're not getting the respect that we deserve,” she said. “I've always said home care workers are the forgotten ones — but now with this COVID-19 going on, it's even worse.”

Barnes works two jobs from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. For one client, she’s paid $9.40 an hour, the other $8.25 an hour. Both of her clients’ care is paid for through Virginia’s Medicaid program. She doesn’t receive benefits through either job and makes slightly too much to qualify for Medicaid herself. She does not have health insurance.

Venkataramani, the health policy professor, believes the coronavirus pandemic should force a reckoning in the industry. “We have to have a tough conversation about whether we are fairly compensating workers who are doing a lot of direct patient contact and who are essential for the functioning of the hospital,” he said. “We have to ask ourselves, ‘Are we in this multibillion-dollar industry valuing the work that these folks do properly?’”

As she gets better, the New Orleans worker is at a crossroads. At $15 an hour, she makes more at her hospital job than she could get working in a hotel or restaurant — income she needs to take care of her son. But she wonders whether it is worth it.

A spokesperson for LCMC Health, which runs the hospital, said it is committed to taking care of all of its employees, whether or not they have health insurance.

“If an LCMC Health employee contracts COVID-19 as a result of work exposure, LCMC Health is committed to paying all medical expenses as it relates to treatment and recovery,” said Mary Beth Romig-Haskins, head of marketing and public affairs. “A top priority is to also ensure our employees have the resources they need to seek screening, testing, and treatment if necessary through our Employee Health program.”

Still, the hospital staffer can’t help wonder what might happen to her family if she dies.

“I'm scared because there's too much uncertainty with this virus,” she said. “Right now, hospitals have to step up and pay people a lot more and have to at least offer some kind of life insurance benefits if we die on the job.”

CORONAVIRUS

Hairstylists Want A Beauty Industry Bailout After Struggling To Get Financial Assistance During The PandemicStephanie K. Baer · May 13, 2020

What You Learn When You Read ObituariesKatherine Miller · May 13, 2020

LGBTQ People Have Become The New Scapegoats For The CoronavirusPatrick Strudwick · May 13, 2020

Emmanuel Felton is an investigative reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.

Contact Emmanuel Felton at emmanuel.felton@buzzfeed.com.

Got a confidential tip? Submit it here.

Posted on May 13, 2020

Chip Somodevilla / Getty Images

An X-ray technician and medical assistant disinfects an examination room in between testing patients for the novel coronavirus on April 15 in Woodbridge, Virginia.

As the novel coronavirus began spreading in the United States in February and March, a clerical worker at the University Medical Center New Orleans was spending her shifts going in and out of patients’ rooms, collecting insurance information

It didn’t take long for her to get sick.

In early March, as coronavirus cases began exploding in the city after Mardi Gras, she came down with chills, body aches, and shortness of breath. When she finally got a test three weeks later, it came back negative for COVID-19. But there are concerns about some tests returning false negatives, and she doesn’t trust that hers was performed correctly. Nearly two months and several hospital visits later, she said she has been stuck at home and hasn’t fully recovered.

When she was risking infection at work, the woman, who asked not to be identified as she feared reprisal from her employer, was earning just $15 an hour. As she is not a full-time employee, unlike the clinical staff at her hospital, she doesn’t get paid sick time or vacation days. She also doesn’t get health insurance. The only reason she isn’t saddled with thousands of dollars of medical debt is that she made so little working at the hospital that she qualified for the state’s Medicaid program, which was recently expanded to include adults earning low incomes like her.

“As a nurse or a doctor, at least you're getting paid a decent amount of money to risk your life,” the woman told BuzzFeed News. “It pisses me off because they're not looking out for the most vulnerable people who don't have benefits.”

She added: “They want people to risk their lives and get paid little to nothing. It's not worth it. It's just not.”

The New Orleans staffer is a part of the healthcare industry’s often overlooked class of hourly workers — home health aides, records clerks, nursing assistants, and hospital janitors — who are risking their lives during the coronavirus pandemic with little or no safety net.

More than 800,000 healthcare workers and almost 1.1 million of their children live in poverty across the US, according to a 2019 study published in the American Journal of Public Health. The researchers found that roughly 18.5 million people are employed in the US health industry. And nearly 10% of them — 1.7 million — earn so little that they get healthcare through Medicaid. Another 1.4 million have no health insurance at all.

A personal care assistant leaves home in Massachusetts to care for an elderly woman in Watertown on March 26.

Women of color, like the New Orleans staffer, are overrepresented in the industry's lowest-paid rungs. Researchers found that nearly half of black and Latina women healthcare workers earned less than $15 an hour.

“It's a vast, unseen, low-paid workforce,” said Atheendar Venkataramani, a professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the study’s authors. “There's a tremendous amount of wage inequality in healthcare, and typically these low-wage jobs are held by women and underrepresented minorities.”

Venkataramani became interested in the topic several years ago when he was a primary care doctor in Massachusetts. One of his patients was a home health aide who earned little more than the state minimum wage and only sporadically had health insurance. “It seemed incredibly unfair to me that this person, who is at some level a colleague of mine — we're both in the same industry, but to provide her medical care required dealing with a number of challenges presented by her socioeconomic circumstances,” he said. “It was kind of an eye-opening experience for me. It didn't seem particularly fair.”

Hospitals employ low-paid workers in a range of different jobs. Some are performing administrative work or answering phones, while others are cooking meals or cleaning rooms or working as security guards. All face a risk of infection during the coronavirus pandemic. Just last week, the New York Times reported on three hospital administrative staffers who were part of the “invisible army” in charge of handing out personal protective equipment at Queens’ Elmhurst Hospital Center and replenishing supplies. All three contracted the coronavirus and died.

Sepia Coleman, a healthcare worker in Memphis, has spent 30 years working in the industry. She still works two jobs, one as a home health aide at $10.50 an hour, and another on the night shift at a nursing home at $12 an hour.

"We are in the room when no one else is,” said Coleman. “Doctors and nurses only come in to do things like administer medications; we're there all the time. We have to make sure their vitals are OK. We have to watch them to see if they have any change in behavior or color. We are beyond essential. We are the main component of the healthcare system, but we get no credit for that.”

Neither of her jobs offers paid sick leave; if she contracts the virus, she has no idea how she will pay her bills.

"I work with sick patients. That's what I do. Why not give us sick pay?” Coleman told BuzzFeed News. “I'm disgusted and I'm really hurt. I knew the healthcare system was broken, but this pandemic has shown their true colors with all the greed and neglect — not just of residents, but of us, too. It's just like they don't care.”

Boston Globe / Getty Images

A medical assistant scans a staff member's identification badge in a personal protective equipment distribution area at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston on March 25.

Joyce Barnes of Richmond, Virginia, has also worked in healthcare for over 30 years. Even in the best of times, she said, working as a home healthcare aide is tough, grueling work. “You don't get any raises. You don't get any vacation time. You don't get paid sick time. You have to work all the time,” she said.

“I've always felt like we're not getting the respect that we deserve,” she said. “I've always said home care workers are the forgotten ones — but now with this COVID-19 going on, it's even worse.”

Barnes works two jobs from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. For one client, she’s paid $9.40 an hour, the other $8.25 an hour. Both of her clients’ care is paid for through Virginia’s Medicaid program. She doesn’t receive benefits through either job and makes slightly too much to qualify for Medicaid herself. She does not have health insurance.

Venkataramani, the health policy professor, believes the coronavirus pandemic should force a reckoning in the industry. “We have to have a tough conversation about whether we are fairly compensating workers who are doing a lot of direct patient contact and who are essential for the functioning of the hospital,” he said. “We have to ask ourselves, ‘Are we in this multibillion-dollar industry valuing the work that these folks do properly?’”

As she gets better, the New Orleans worker is at a crossroads. At $15 an hour, she makes more at her hospital job than she could get working in a hotel or restaurant — income she needs to take care of her son. But she wonders whether it is worth it.

A spokesperson for LCMC Health, which runs the hospital, said it is committed to taking care of all of its employees, whether or not they have health insurance.

“If an LCMC Health employee contracts COVID-19 as a result of work exposure, LCMC Health is committed to paying all medical expenses as it relates to treatment and recovery,” said Mary Beth Romig-Haskins, head of marketing and public affairs. “A top priority is to also ensure our employees have the resources they need to seek screening, testing, and treatment if necessary through our Employee Health program.”

Still, the hospital staffer can’t help wonder what might happen to her family if she dies.

“I'm scared because there's too much uncertainty with this virus,” she said. “Right now, hospitals have to step up and pay people a lot more and have to at least offer some kind of life insurance benefits if we die on the job.”

CORONAVIRUS

Hairstylists Want A Beauty Industry Bailout After Struggling To Get Financial Assistance During The PandemicStephanie K. Baer · May 13, 2020

What You Learn When You Read ObituariesKatherine Miller · May 13, 2020

LGBTQ People Have Become The New Scapegoats For The CoronavirusPatrick Strudwick · May 13, 2020

Emmanuel Felton is an investigative reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.

Contact Emmanuel Felton at emmanuel.felton@buzzfeed.com.

Got a confidential tip? Submit it here.