Recently conservatives in Canada and the USA have been voicing concern that heaven to betsy folks might be making more money with the Canadian CERB and topped up EI while in the States it's the top up to Unemployment as well as PPP etc.

That's right the average wages for most workers are at $15 an hour as minimum wage, a real living wage should be $20-$25 per hour based on a monthly basket of goods to keep you alive. Workers in meatpacking plants and hospital staff in US hospitals make $15 per hour, whereas in Canada the wages are closer to the later.

The right wing is correct to be concerned that with all the top ups and in fact in Canada the CERB being $2000 per month is a Universal Basic Income, which causes our ex paper boy leader of the Conservatives to worry someone might being getting more than they should. That of course would never cross his mind to say about a McCain or a Galen Weston or an Irving.

Suddenly with workers making more money with CERB or EI they might not want to go back to work cries the conservative. So lets look at that closer. Why would the workers not want to go back to a low paying job, and why is that job low waged, below even $15 per hour if that wage is not the provincial or state rate. So it seems to me the conservative should be wagging his finger in the direction of the bosses, and tell them that if they want to keep their workers they have to offer them more!! Not demand they take less than they are making now which is between $15 and $25 pr hour and in fact I would suggest that benefits be tossed in too and some flex time.

Our conservative views the employee as a thief, of course they do they represent their class the small shop keeper.

But the real thief is the employer, the boss who would pocket the difference between minimum wage and the days earnings.

The real kicker though is the fact that as workers earning a living we spend our paychecks as soon as we get them, we have barely $400 in our bank accounts between us and poverty, but we should save for that rainy pandemic day.

When we spend our earnings as wage slaves we suddenly Cinderella like change into the mighty Consumer the very soul and essence of late capitalism.

The conservative completely fails to understand that it is not shovels in the ground, not pipelines, or Wall St that keeps capitalism functioning, it is me and you with our credit cards, our car payments and our rent or mortgages, let alone our entertainment and food purchases. https://edmontonsocialplanning.ca/

What part of Capitalism collapsed because of the Coronavirus, the consumer capitalist market place. Wall St. and the other stock exchanges didn't even as they crashed and rose again like the Mary Ellen Carter. The bourse is divorced from reality and main street, moving money to make more money, M=C=M regardless if the actual political economy is crashing or not, they sell the market short in that case.

When the Oracle of Omaha Warren Buffet and his Berkshire Hathaway spend millions and billions investing that does not drive capitalism as much as his munching on a ice cream bar and drinking a coke, the later are the real capitalist exchange.

Late capitalism is the great equalizer, Bill Gates makes millions daily in the stock market, but that is not when he really makes capitalism function, its when he and Melinda go out for a Big Mac at the drive through. It is when they go to Starbucks or order something from Amazon, when they consume. In late capitalism with finance capital dominating the market the real marketplace is that of consumption not production or even wealth creation it is us consuming and getting into debt.

The minimum wage worker contributes more to capitalism functioning than a hundred Jeff Bezos. It is our consumption that drives the post modern market place, and the more money in our hands the better off capitalism will be as we have seen for the past two months of this pandemic panic.

SEE

THE RIGHT TO BE GREEDY

THE RIGHT TO BE LAZY

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Saturday, May 16, 2020

Trump’s grade on the economy tumbles from B to C to 'F'

Rick Newman Senior Columnist Yahoo Finance May 13, 2020

For most of his presidency, Donald Trump’s grade on the Yahoo Finance Trumponomics Report Card was a respectable B. But in one month it has dropped to C, and it may be heading to D.

Since Trump took office, Yahoo Finance has been grading the Trump economy compared with six prior presidents, using data provided by Moody’s Analytics. We use common metrics such as job gains, earnings and stock values, measuring improvements since Trump took office against prior presidents at the same point in their first term.

The coronavirus outbreak and the business shutdowns it has caused have dramatically eroded Trump’s standing against other presidents. Before the outbreak, Trump ranked first in earnings gains, second in manufacturing employment, and third in total employment. This is where he ranks now:

View photos

Sources: Yahoo Finance, Moody's AnalyticsMore

Here’s a breakdown for each of the six indicators we track:

Total employment. In February, job gains under Trump totaled 6.8 million, third best after Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton at the same point in their presidencies. But massive job losses during the last two months have wiped out all those gains and more, for a net job loss under Trump of 14.6 million. That’s the worst performance of any of the seven presidents, going back to Carter, by far. The second worst performance was a loss of 1.3 million jobs at the same point in George W. Bush’s presidency, followed by 221,000 job losses under Obama. Both of those presidents began their first terms with a troubled economy. Trump, by contrast, inherited a relatively strong economy.

Manufacturing employment. Manufacturers have shed 881,000 jobs under Trump, which is not as bad as the 2.8 million lost under George W. Bush or the 1.2 million lost under his father, George H. W. Bush. But data during the next two months is almost certain to show many more lost jobs, so Trump could fall another notch or two here.

Average hourly earnings. Trump’s record here is the best, and it will probably stay that way. Wages tend to be “sticky,” even during downturns, since employers are more likely to shrink their workforce than cut pay. Trump’s strength on this measure probably comes from the fact that he took office in the eighth year of an economic expansion, with the labor market tightening, forcing wages up. Overall, wage growth has slowed during the last 30 years, generating weak numbers for most of the seven presidents.

View photos

Graphic by David FosterMore

Exports. This has been a weakness for Trump since he began imposing tariffs on China and other importers in 2018, triggering retaliatory measures that have reduced trade overall. Making that worse, U.S. exports typically fall during recessions, since foreigners buy less American-made stuff.

The S&P 500 stock index. Stocks are down 11% this year, but they’ve rebounded from March lows as investors anticipate an economic recovery later this year. Stocks are also benefiting from massive amounts of Federal Reserve monetary stimulus meant to ease liquidity pressures and restore confidence in markets.

GDP per capita. In February, Trump ranked second best on this metric, but with a big falloff in output during March, he has fallen to third worst. GDP numbers for the second quarter are going to be dramatically worse, probably worse than any single quarter during the Great Depression in the 1930s. So Trump is likely to end up with the lowest score in this category by summer.

If Trump notches the lowest marks for manufacturing employment and GDP, and everything else stays the same, his grade will fall to D+, according to our methodology. If the stock market executes another nose dive, Trump’s grade would fall to a straight D. There could also be improvements in some of these metrics, but economists don’t think that’s likely until the third quarter at the very earliest. Many economists don’t expect meaningful improvement in the economy until 2021.

We’ve said all along that presidents deserve less blame (or credit) for what happens to the economy under their watch than they typically get. Many forces presidents can’t control—including microscopic pathogens — determine the course of the economy. But voters hold the president accountable for the economy anyway, with no president since Calvin Coolidge in 1924 winning reelection in the midst or aftermath of a recession. Trump faces steep odds in November, and they’re probably going to get steeper

For most of his presidency, Donald Trump’s grade on the Yahoo Finance Trumponomics Report Card was a respectable B. But in one month it has dropped to C, and it may be heading to D.

Since Trump took office, Yahoo Finance has been grading the Trump economy compared with six prior presidents, using data provided by Moody’s Analytics. We use common metrics such as job gains, earnings and stock values, measuring improvements since Trump took office against prior presidents at the same point in their first term.

The coronavirus outbreak and the business shutdowns it has caused have dramatically eroded Trump’s standing against other presidents. Before the outbreak, Trump ranked first in earnings gains, second in manufacturing employment, and third in total employment. This is where he ranks now:

View photos

Sources: Yahoo Finance, Moody's AnalyticsMore

Here’s a breakdown for each of the six indicators we track:

Total employment. In February, job gains under Trump totaled 6.8 million, third best after Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton at the same point in their presidencies. But massive job losses during the last two months have wiped out all those gains and more, for a net job loss under Trump of 14.6 million. That’s the worst performance of any of the seven presidents, going back to Carter, by far. The second worst performance was a loss of 1.3 million jobs at the same point in George W. Bush’s presidency, followed by 221,000 job losses under Obama. Both of those presidents began their first terms with a troubled economy. Trump, by contrast, inherited a relatively strong economy.

Manufacturing employment. Manufacturers have shed 881,000 jobs under Trump, which is not as bad as the 2.8 million lost under George W. Bush or the 1.2 million lost under his father, George H. W. Bush. But data during the next two months is almost certain to show many more lost jobs, so Trump could fall another notch or two here.

Average hourly earnings. Trump’s record here is the best, and it will probably stay that way. Wages tend to be “sticky,” even during downturns, since employers are more likely to shrink their workforce than cut pay. Trump’s strength on this measure probably comes from the fact that he took office in the eighth year of an economic expansion, with the labor market tightening, forcing wages up. Overall, wage growth has slowed during the last 30 years, generating weak numbers for most of the seven presidents.

View photos

Graphic by David FosterMore

Exports. This has been a weakness for Trump since he began imposing tariffs on China and other importers in 2018, triggering retaliatory measures that have reduced trade overall. Making that worse, U.S. exports typically fall during recessions, since foreigners buy less American-made stuff.

The S&P 500 stock index. Stocks are down 11% this year, but they’ve rebounded from March lows as investors anticipate an economic recovery later this year. Stocks are also benefiting from massive amounts of Federal Reserve monetary stimulus meant to ease liquidity pressures and restore confidence in markets.

GDP per capita. In February, Trump ranked second best on this metric, but with a big falloff in output during March, he has fallen to third worst. GDP numbers for the second quarter are going to be dramatically worse, probably worse than any single quarter during the Great Depression in the 1930s. So Trump is likely to end up with the lowest score in this category by summer.

If Trump notches the lowest marks for manufacturing employment and GDP, and everything else stays the same, his grade will fall to D+, according to our methodology. If the stock market executes another nose dive, Trump’s grade would fall to a straight D. There could also be improvements in some of these metrics, but economists don’t think that’s likely until the third quarter at the very earliest. Many economists don’t expect meaningful improvement in the economy until 2021.

We’ve said all along that presidents deserve less blame (or credit) for what happens to the economy under their watch than they typically get. Many forces presidents can’t control—including microscopic pathogens — determine the course of the economy. But voters hold the president accountable for the economy anyway, with no president since Calvin Coolidge in 1924 winning reelection in the midst or aftermath of a recession. Trump faces steep odds in November, and they’re probably going to get steeper

Working from home impact on business productivity

Working from home might not be so bad for productivity after all.

A new survey from tech workplace advisory firm Valoir reveals that the shift to working from home might only be reducing overall worker productivity by a marginal 1%.

The survey, which polled more than 325 workers from around North America, also showed that about 40% of workers would prefer to work from home in the future rather than return to an office environment.

Interestingly, the survey also found parents to be reporting a smaller drop in productivity compared to workers without children. Parents reported a 2% drop to productivity in the work-from-home environment compared to the 3% drop for workers without kids at home.

Kids are reportedly less of a distraction when working at home than social media, according to a new survey.More

“Parents have a slightly bigger productivity hit of 2% on average, but the folks that really were hit were those who were working alone without anybody else in their house to talk to,” said Valoir CEO Rebecca Wettemann.

Workers surveyed generally reported the negatives of distractions at home being offset by the positive that came with eliminating commute time. On average, workers reported a nearly 10-hour workday, starting at 8:15 a.m. and ending around 6 p.m.

While some workers enjoyed eliminating the workplace distractions, the most common distraction at home has become social media, with workers estimating it eats up about two hours of productivity.

“People are getting a lot of distractions from places that you might not expect, with social media being the biggest distraction folks commented on even for those folks who had kids at home,” Wettemann said.

Despite the reported lack of a drop in productivity, workers still appear worried about job security in the work-from-home environment, according to the survey’s findings.

“When we asked people what they were most concerned about — we didn't say about the work environment but just in general - and more than a third of them said that they were worried about their job and job security which rated far ahead of worried about being sick or worried about a loved one getting ill,” Wettemann said.

Working from home might not be so bad for productivity after all.

A new survey from tech workplace advisory firm Valoir reveals that the shift to working from home might only be reducing overall worker productivity by a marginal 1%.

The survey, which polled more than 325 workers from around North America, also showed that about 40% of workers would prefer to work from home in the future rather than return to an office environment.

Interestingly, the survey also found parents to be reporting a smaller drop in productivity compared to workers without children. Parents reported a 2% drop to productivity in the work-from-home environment compared to the 3% drop for workers without kids at home.

Kids are reportedly less of a distraction when working at home than social media, according to a new survey.More

“Parents have a slightly bigger productivity hit of 2% on average, but the folks that really were hit were those who were working alone without anybody else in their house to talk to,” said Valoir CEO Rebecca Wettemann.

Workers surveyed generally reported the negatives of distractions at home being offset by the positive that came with eliminating commute time. On average, workers reported a nearly 10-hour workday, starting at 8:15 a.m. and ending around 6 p.m.

While some workers enjoyed eliminating the workplace distractions, the most common distraction at home has become social media, with workers estimating it eats up about two hours of productivity.

“People are getting a lot of distractions from places that you might not expect, with social media being the biggest distraction folks commented on even for those folks who had kids at home,” Wettemann said.

Despite the reported lack of a drop in productivity, workers still appear worried about job security in the work-from-home environment, according to the survey’s findings.

“When we asked people what they were most concerned about — we didn't say about the work environment but just in general - and more than a third of them said that they were worried about their job and job security which rated far ahead of worried about being sick or worried about a loved one getting ill,” Wettemann said.

Whistleblower: Wall Street has engaged in widespread manipulation of mortgage funds

May 16, 2020 By Pro Publica

Among the toxic contributors to the financial crisis of 2008, few caused as much havoc as mortgages with dodgy numbers and inflated values. Huge quantities of them were assembled into securities that crashed and burned, damaging homeowners and investors alike. Afterward, reforms were promised. Never again, regulators vowed, would real estate financiers be able to fudge numbers and threaten the entire economy.

Twelve years later, there’s evidence something similar is happening again.

Some of the world’s biggest banks — including Wells Fargo and Deutsche Bank — as well as other lenders have engaged in a systematic fraud that allowed them to award borrowers bigger loans than were supported by their true financials, according to a previously unreported whistleblower complaint submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission last year.

Whereas the fraud during the last crisis was in residential mortgages, the complaint claims this time it’s happening in commercial properties like office buildings, apartment complexes and retail centers. The complaint focuses on the loans that are gathered into pools whose worth can exceed $1 billion and turned into bonds sold to investors, known as CMBS (for commercial mortgage-backed securities).

Lenders and securities issuers have regularly altered financial data for commercial properties “without justification,” the complaint asserts, in ways that make the properties appear more valuable, and borrowers more creditworthy, than they actually are. As a result, it alleges, borrowers have qualified for commercial loans they normally would not have, with the investors who bought securities birthed from those loans none the wiser.

ProPublica closely examined six loans that were part of CMBS in recent years to see if their data resembles the pattern described by the whistleblower. What we found matched the allegations: The historical profits reported for some buildings were listed as much as 30% higher than the profits previously reported for the same buildings and same years when the property was part of an earlier CMBS. As a rough analogy, imagine a homeowner having stated in a mortgage application that his 2017 income was $100,000 only to claim during a later refinancing that his 2017 income was $130,000 — without acknowledging or explaining the change.

It’s “highly questionable” to alter past profits with no apparent explanation, said John Coffee, a professor at Columbia Law School and an expert in securities regulation. “I don’t understand why you can do that.”

In theory, CMBS are supposed to undergo a rigorous multistage vetting process. A property owner seeking a loan on, say, an office building would have its finances scrutinized by a bank or other lender. After that loan is made, it would be subjected to another round of due diligence, this time by an investment bank that assembles 60 to 120 loans to form a CMBS. Somewhere along the line, according to John Flynn, a veteran of the CMBS industry who filed the whistleblower complaint, numbers are being adjusted — inevitably to make properties, and therefore the entire CMBS, look more financially robust.

The complaint suggests widespread efforts to make adjustments. Some expenses were erased from the ledger, for example, when a new loan was issued. Most changes were small; but a minor increase in profits can lead to approval for a significantly higher mortgage.

The result: Many properties may have borrowed more than they could afford to pay back — even before the pandemic rocked their businesses — making a CMBS crash both more likely and more damaging. “It’s a higher cliff from which they are falling,” Flynn said. “So the loss severity is going to be greater and the probability of default is going to be greater.”

With the economy being pounded and trillions of dollars already committed to bailouts, potential overvaluations in commercial real estate loom much larger than they would have even a few months ago. Data from early April showed a sharp spike in missed payments to bondholders for CMBS that hold loans from hotels and retail stores, according to Trepp, a data provider whose specialties include CMBS. The default rate is expected to climb as large swaths of the nation remain locked down.

After lobbying by commercial real estate organizations and advocacy by real estate investor and Trump ally Tom Barrack — who warned of a looming commercial mortgage crash — the Federal Reservepledged in early April to prop up CMBS by loaning money to investors and letting them use their CMBS as collateral. The goal is to stabilize the market at a time when investors may be tempted to dump their securities, and also to support banks in issuing new bonds. (Barrack’s company, Colony Capital, has since defaulted on $3.2 billion in debt backed by hotel and health care properties, according to the Financial Times.)

The Fed didn’t specify how much it’s willing to spend to support the CMBS, and it is allowing only those with the highest credit ratings to be used as collateral. But if some ratings are based on misleading data, as the complaint alleges, taxpayers could be on the hook for a riskier-than-anticipated portfolio of loans.

The SEC, which has not taken public action on the whistleblower complaint, declined to comment.

Some lenders interviewed for this article maintain they’re permitted to alter properties’ historical profits under some circumstances. Others in the industry offered a different view. Adam DeSanctis, a spokesperson for the Mortgage Bankers Association, which has helped set guidelines for financial reporting in CMBS, said he reached out to members of the group’s commercial real estate team and none had heard of a practice of inflating profits. “We aren’t aware of this occurring and really don’t have anything to add,” he said.

The notion that profit figures for some buildings are pumped up is surprising, said Kevin Riordan, a finance professor at Montclair State University. It raises questions about whether the proper disclosures are being made.

Investors don’t comb through financial statements, added Riordan, who used to manage the CMBS portfolio for retirement fund giant TIAA-CREF. Instead, he said, they rely on summaries from investment banks and the credit ratings agencies that analyze the securities. To make wise decisions, investors’ information “out of the gate has to be pretty close to being right,” he said. “Otherwise you’re dealing with garbage. Garbage in, garbage out.”

The whistleblower complaint has its origins in the kinds of obsessions that keep wonkish investors up at night. Flynn wondered what was going to happen when some of the most ill-conceived commercial loans — those made in the lax, freewheeling days before the financial crisis of 2008 — matured a decade later. He imagined an impending disaster of mass defaults. But as 2015, then 2017, passed, the defaults didn’t come. It didn’t make sense to him.

Flynn, 55, has deep experience in commercial real estate, banking and CMBS. After growing up on a dairy farm in Minnesota, the youngest of 14 children, and graduating from college — the first in his family to do so, he said — Flynn moved to Tokyo to work, first in real estate, then in finance. Jobs with banks and ratings agencies took him to Belgium, Chicago and Australia. These days, he advises owners whose loans are sold into CMBS and helps them resolve disputes and restructure or modify problem loans.

He began poring over the fine print in CMBS filings and noticed curious anomalies. For example, many properties changed their names, and even their addresses, from one CMBS to another. That made it harder to recognize a specific property and compare its financial details in two filings. As Flynn read more and more, he began to wonder whether the alterations were attempts to obscure discrepancies: These same properties were typically reporting higher net operating incomes in the new CMBS than they did for the same year in a previous CMBS.

Flynn ultimately collected and analyzed data for huge numbers of commercial mortgages. He began to see patterns and what he calls a massive problem: Flynn has amassed “materials identifying about $150 billion in inflated CMBS issued between 2013 and today,” according to the complaint.

The higher reported profits helped the properties qualify for loans they might not have otherwise obtained, he surmised. They also paved the way for bigger fees for banks. “Inflating historical cash flows creates a misperception of lower current and historical cash flow volatility, enables higher underwritten [net operating income/net cash flow], and higher collateral values,” the complaint states, “and thereby enables higher debt.”

Flynn eventually found a lawyer and, in February 2019, he filed the whistleblower complaint. The complaint accuses 14 major lenders — including three of the country’s biggest CMBS issuers, Deutsche Bank, Wells Fargo and Ladder Capital — and seven servicers of inflating historical cash flows, failing to report misrepresentations, changing names and addresses of properties and “deceptively and inaccurately” describing mortgage-loan representations. It doesn’t identify which companies allegedly manipulated each specific number. (Spokespeople for Deutsche Bank and Wells Fargo declined to comment on the record. The complaint does not mention Barrack or his company. )

The SEC has the power to fine companies and their executives if fraud is established. If the SEC recovers more than $1 million based on Flynn’s claim, he could be entitled to a portion of it.

When Flynn filed the complaint, the skies looked clear for the commercial mortgage market. Indeed, last year was a boom year for CMBS, with private lenders in the U.S. issuing roughly $96.7 billion in commercial mortgage-backed securities — a 27% increase over 2018, which made it the most successful year since the last financial crisis, according to Trepp. Overall, investors hold CMBS worth $592 billion.

Flynn’s assertions raise questions about the efficacy of post-crisis reforms that Congress and the SEC instituted that sought to place new restrictions on banks and other lenders, increase transparency and protect consumers and investors. The regulations that were retooled included the one that governs CMBS, known as Regulation AB. The goal was to make disclosures clearer and more complete for investors, so they would be less reliant on ratings agencies, which were widely criticized during the financial crisis for lax practices.

Still, the opinion of the credit-ratings agencies remains crucial today, a point reinforced by the Fed’s decision to hinge its bailout decisions on those ratings. That’s a problem, in the view of Neil Barofsky, who served as the U.S. Treasury’s inspector general for the Troubled Assets Relief Program from 2008 to 2011. “Practically nothing” was done to reform the ratings agencies, Barofsky said, which could lead to the sorts of problems that emerged in the bailout a decade ago. If things truly turn bad for the commercial real estate industry or if fraud is discovered, he added, the Fed could end up taking possession of properties that default.

CMBS can be something of a last resort for borrowers whose projects are unlikely to qualify for a loan with a desirable interest rate from a bank or other lender (because they are too big, too risky or some other reason), according to experts. Underwriting practices — the due diligence lenders do before extending a loan — for CMBS have gained a reputation for being less strict than for loans that banks keep on their balance sheets. Government watchdogs found serious deficiencies in the underwriting for securitized commercial mortgages during the financial crisis, just as they did in the subprime residential market.

The due diligence process broke down, Flynn maintains, in precisely the mortgages he was worried about: the 10-year loans obtained before the financial crisis. What Flynn discovered, he said, was that rather than lowering the values for properties that had taken on bigger loans than they could pay off, their owners instead obtained new loans. “Someone should have taken the losses,” he said. “Instead, they papered over it, inflated the cash flow and sold it on.”

For commercial borrowers, small bumps in a property’s profits can qualify the borrower for millions more in loans. Shaving expenses by about a third to boost profit, for instance, can sometimes allow a borrower to increase a loan’s size by a third as well — even if the expenses run only in the thousands, and the loan runs in the millions.

Some executives for lenders acknowledged to ProPublica that they made changes to borrowers’ past financials — scrubbing expenses from prior years they deemed irrelevant for the new loan — but maintained that it is appropriate to do so. Accounting firms review financial data before the loans are assembled into CMBS, they added.

The financial data that ProPublica examined — a sample of six loans among the thousands Flynn identified as having inflated net operating income — revealed potential weaknesses not readily apparent to the average investor. For those six loans, the profits for a given year were listed as 9% to 30% higher in new securities than in the old. After they were issued, half of those loans ended up on watch lists for problem debt, meaning the properties were considered at heightened risk for default.

In each of the six loans, the profit inflation seemed to be explained by decreases in the costs reported. Expenses reported for a particular year in one CMBS simply vanished in disclosures for the same year in a new CMBS.

Such a pattern appeared in a $36.7 million loan by Ladder Capital in 2015 to a team that purchased the Doubletree San Diego, a half-century-old hotel that struggled for years to bring in enough income to satisfy loan servicers, even under a previous, smaller loan.

The hotel’s new loan saddled it with far greater debt, increasing its main loan by 60% — even though the property had landed on a watchlist in 2010 because of declining revenue. Analysts at Moody’s pegged the hotel’s new loan as exceeding the value of the property by 40.5% (meaning a loan-to-value ratio of 140.5%).

Filings for the new loan claimed much higher profits than what the old loan had cited for the same years: The hotel’s net operating income for two years magically jumped from what had previously been reported: 21% and 16% larger for 2013 and 2014, respectively.

Such figures are supposed to be pulled from a property’s “most recent operating statement,” according to the regulation governing CMBS disclosures.

But, in response to questions from ProPublica, lender Ladder Capital said it altered the expense numbers it provided in the Doubletree’s historical financials. Ladder said it wiped lease payments —$700,608 and $592,823 in those two years — from the historical financials, because the new owner would not make lease payments in the future. (The previous owner had leased the building from an affiliated company.)

Ladder, a publicly traded commercial real estate investment trust that reports more than $6 billion in assets, said in a statement, “These differences are due to items that were considered by Ladder Capital during the due diligence process and reported appropriately in all relevant disclosures.”

Yet when ProPublica asked Ladder to share its disclosures about the changes, the firm pointed to a section of the pool’s prospectus that didn’t mention lease payments, or explain or acknowledge the change in income.

The Doubletree did not fare well under its new debt package. Revenues and occupancy declined after 2015 and by 2017, the hotel’s loan was back on the watch list. The hotel missed franchise fee payments. Ladder foreclosed in December 2019, after problems with an additional $5.8 million loan the lender had extended the property.

The Doubletree loan was not the only loan in its CMBS pool, issued by Deutsche Bank in 2015, with apparently inflated profits. Flynn said he was able to track down previous loan information for loans representing nearly 40% of the pool, and all had inflated income figures at some point in their historical financial data.

There was also a noticeable profit increase in two loans Ladder issued for a strip mall in suburban Pennsylvania. The mall’s past results improved when they appeared in a new CMBS. Its 2016 net operating income, previously listed as $1,101,207 in one CMBS, now appeared as $1,352,353 in another, data from Trepp shows — an increase of 23%. The prospectus for the latter does not explain or acknowledge the change in income. The mall owner received a $14 million loan.

Less than a year after it was placed into a CMBS, the loan ran into trouble. It landed on a watchlist after one of its major tenants, a department store, declared bankruptcy.

Ladder said it excluded $203,787 in expenses from the new loan because they stemmed from one-time costs for environmental remediation of pollution by a dry cleaner and a roof repair. Ladder did not explain why the previous lender did not exclude the expense also.

The pattern can be seen in loans made by other lenders, too. In a CMBS issued by Wells Fargo, a 1950s-era trailer park at the base of a steep bluff along the coast in Los Angeles reported sharply higher profits — for the same years — than it previously had.

The Pacific Palisades Bowl Park received a $12.9 million loan from the bank in 2016. The park reported expenses that were about a third lower in its new loan disclosures when compared with earlier ones. As a result, the $1.2 million in net operating income for 2014 rose 28% above what had been reported for the same year under the old loan. A similar jump occurred in 2013. (Edward Biggs, the owner of the park, said he gave Wells Fargo the park’s financials when refinancing its loan and wasn’t aware of discrepancies in what was reported to investors. “I don’t know anything about that,” he said.)

Flynn said he found that for the $575 million Wells Fargo CMBS that contained the Palisades debt, about half of the loan pool appeared to have reported inflated profits at some point, when comparing the same years in different securities.

Another of the loans ProPublica examined with apparently inflated profits was for a building in downtown Philadelphia. When the owner refinanced through Wells Fargo, the property’s 2015 profit appeared 23% higher than it had in reports under the old loan. Wells bundled the debt into a mortgage-backed security in 2016.

The building, One Penn Center, is a historic Art Deco office high-rise with ornate black marble and gold-plated fixtures, and a transit station underneath. One of the primary tenants, leasing 45,000 square feet for one of its regional headquarters, happens to be the SEC. The agency declined to comment.

May 16, 2020 By Pro Publica

Among the toxic contributors to the financial crisis of 2008, few caused as much havoc as mortgages with dodgy numbers and inflated values. Huge quantities of them were assembled into securities that crashed and burned, damaging homeowners and investors alike. Afterward, reforms were promised. Never again, regulators vowed, would real estate financiers be able to fudge numbers and threaten the entire economy.

Twelve years later, there’s evidence something similar is happening again.

Some of the world’s biggest banks — including Wells Fargo and Deutsche Bank — as well as other lenders have engaged in a systematic fraud that allowed them to award borrowers bigger loans than were supported by their true financials, according to a previously unreported whistleblower complaint submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission last year.

Whereas the fraud during the last crisis was in residential mortgages, the complaint claims this time it’s happening in commercial properties like office buildings, apartment complexes and retail centers. The complaint focuses on the loans that are gathered into pools whose worth can exceed $1 billion and turned into bonds sold to investors, known as CMBS (for commercial mortgage-backed securities).

Lenders and securities issuers have regularly altered financial data for commercial properties “without justification,” the complaint asserts, in ways that make the properties appear more valuable, and borrowers more creditworthy, than they actually are. As a result, it alleges, borrowers have qualified for commercial loans they normally would not have, with the investors who bought securities birthed from those loans none the wiser.

ProPublica closely examined six loans that were part of CMBS in recent years to see if their data resembles the pattern described by the whistleblower. What we found matched the allegations: The historical profits reported for some buildings were listed as much as 30% higher than the profits previously reported for the same buildings and same years when the property was part of an earlier CMBS. As a rough analogy, imagine a homeowner having stated in a mortgage application that his 2017 income was $100,000 only to claim during a later refinancing that his 2017 income was $130,000 — without acknowledging or explaining the change.

It’s “highly questionable” to alter past profits with no apparent explanation, said John Coffee, a professor at Columbia Law School and an expert in securities regulation. “I don’t understand why you can do that.”

In theory, CMBS are supposed to undergo a rigorous multistage vetting process. A property owner seeking a loan on, say, an office building would have its finances scrutinized by a bank or other lender. After that loan is made, it would be subjected to another round of due diligence, this time by an investment bank that assembles 60 to 120 loans to form a CMBS. Somewhere along the line, according to John Flynn, a veteran of the CMBS industry who filed the whistleblower complaint, numbers are being adjusted — inevitably to make properties, and therefore the entire CMBS, look more financially robust.

The complaint suggests widespread efforts to make adjustments. Some expenses were erased from the ledger, for example, when a new loan was issued. Most changes were small; but a minor increase in profits can lead to approval for a significantly higher mortgage.

The result: Many properties may have borrowed more than they could afford to pay back — even before the pandemic rocked their businesses — making a CMBS crash both more likely and more damaging. “It’s a higher cliff from which they are falling,” Flynn said. “So the loss severity is going to be greater and the probability of default is going to be greater.”

With the economy being pounded and trillions of dollars already committed to bailouts, potential overvaluations in commercial real estate loom much larger than they would have even a few months ago. Data from early April showed a sharp spike in missed payments to bondholders for CMBS that hold loans from hotels and retail stores, according to Trepp, a data provider whose specialties include CMBS. The default rate is expected to climb as large swaths of the nation remain locked down.

After lobbying by commercial real estate organizations and advocacy by real estate investor and Trump ally Tom Barrack — who warned of a looming commercial mortgage crash — the Federal Reservepledged in early April to prop up CMBS by loaning money to investors and letting them use their CMBS as collateral. The goal is to stabilize the market at a time when investors may be tempted to dump their securities, and also to support banks in issuing new bonds. (Barrack’s company, Colony Capital, has since defaulted on $3.2 billion in debt backed by hotel and health care properties, according to the Financial Times.)

The Fed didn’t specify how much it’s willing to spend to support the CMBS, and it is allowing only those with the highest credit ratings to be used as collateral. But if some ratings are based on misleading data, as the complaint alleges, taxpayers could be on the hook for a riskier-than-anticipated portfolio of loans.

The SEC, which has not taken public action on the whistleblower complaint, declined to comment.

Some lenders interviewed for this article maintain they’re permitted to alter properties’ historical profits under some circumstances. Others in the industry offered a different view. Adam DeSanctis, a spokesperson for the Mortgage Bankers Association, which has helped set guidelines for financial reporting in CMBS, said he reached out to members of the group’s commercial real estate team and none had heard of a practice of inflating profits. “We aren’t aware of this occurring and really don’t have anything to add,” he said.

The notion that profit figures for some buildings are pumped up is surprising, said Kevin Riordan, a finance professor at Montclair State University. It raises questions about whether the proper disclosures are being made.

Investors don’t comb through financial statements, added Riordan, who used to manage the CMBS portfolio for retirement fund giant TIAA-CREF. Instead, he said, they rely on summaries from investment banks and the credit ratings agencies that analyze the securities. To make wise decisions, investors’ information “out of the gate has to be pretty close to being right,” he said. “Otherwise you’re dealing with garbage. Garbage in, garbage out.”

The whistleblower complaint has its origins in the kinds of obsessions that keep wonkish investors up at night. Flynn wondered what was going to happen when some of the most ill-conceived commercial loans — those made in the lax, freewheeling days before the financial crisis of 2008 — matured a decade later. He imagined an impending disaster of mass defaults. But as 2015, then 2017, passed, the defaults didn’t come. It didn’t make sense to him.

Flynn, 55, has deep experience in commercial real estate, banking and CMBS. After growing up on a dairy farm in Minnesota, the youngest of 14 children, and graduating from college — the first in his family to do so, he said — Flynn moved to Tokyo to work, first in real estate, then in finance. Jobs with banks and ratings agencies took him to Belgium, Chicago and Australia. These days, he advises owners whose loans are sold into CMBS and helps them resolve disputes and restructure or modify problem loans.

He began poring over the fine print in CMBS filings and noticed curious anomalies. For example, many properties changed their names, and even their addresses, from one CMBS to another. That made it harder to recognize a specific property and compare its financial details in two filings. As Flynn read more and more, he began to wonder whether the alterations were attempts to obscure discrepancies: These same properties were typically reporting higher net operating incomes in the new CMBS than they did for the same year in a previous CMBS.

Flynn ultimately collected and analyzed data for huge numbers of commercial mortgages. He began to see patterns and what he calls a massive problem: Flynn has amassed “materials identifying about $150 billion in inflated CMBS issued between 2013 and today,” according to the complaint.

The higher reported profits helped the properties qualify for loans they might not have otherwise obtained, he surmised. They also paved the way for bigger fees for banks. “Inflating historical cash flows creates a misperception of lower current and historical cash flow volatility, enables higher underwritten [net operating income/net cash flow], and higher collateral values,” the complaint states, “and thereby enables higher debt.”

Flynn eventually found a lawyer and, in February 2019, he filed the whistleblower complaint. The complaint accuses 14 major lenders — including three of the country’s biggest CMBS issuers, Deutsche Bank, Wells Fargo and Ladder Capital — and seven servicers of inflating historical cash flows, failing to report misrepresentations, changing names and addresses of properties and “deceptively and inaccurately” describing mortgage-loan representations. It doesn’t identify which companies allegedly manipulated each specific number. (Spokespeople for Deutsche Bank and Wells Fargo declined to comment on the record. The complaint does not mention Barrack or his company. )

The SEC has the power to fine companies and their executives if fraud is established. If the SEC recovers more than $1 million based on Flynn’s claim, he could be entitled to a portion of it.

When Flynn filed the complaint, the skies looked clear for the commercial mortgage market. Indeed, last year was a boom year for CMBS, with private lenders in the U.S. issuing roughly $96.7 billion in commercial mortgage-backed securities — a 27% increase over 2018, which made it the most successful year since the last financial crisis, according to Trepp. Overall, investors hold CMBS worth $592 billion.

Flynn’s assertions raise questions about the efficacy of post-crisis reforms that Congress and the SEC instituted that sought to place new restrictions on banks and other lenders, increase transparency and protect consumers and investors. The regulations that were retooled included the one that governs CMBS, known as Regulation AB. The goal was to make disclosures clearer and more complete for investors, so they would be less reliant on ratings agencies, which were widely criticized during the financial crisis for lax practices.

Still, the opinion of the credit-ratings agencies remains crucial today, a point reinforced by the Fed’s decision to hinge its bailout decisions on those ratings. That’s a problem, in the view of Neil Barofsky, who served as the U.S. Treasury’s inspector general for the Troubled Assets Relief Program from 2008 to 2011. “Practically nothing” was done to reform the ratings agencies, Barofsky said, which could lead to the sorts of problems that emerged in the bailout a decade ago. If things truly turn bad for the commercial real estate industry or if fraud is discovered, he added, the Fed could end up taking possession of properties that default.

CMBS can be something of a last resort for borrowers whose projects are unlikely to qualify for a loan with a desirable interest rate from a bank or other lender (because they are too big, too risky or some other reason), according to experts. Underwriting practices — the due diligence lenders do before extending a loan — for CMBS have gained a reputation for being less strict than for loans that banks keep on their balance sheets. Government watchdogs found serious deficiencies in the underwriting for securitized commercial mortgages during the financial crisis, just as they did in the subprime residential market.

The due diligence process broke down, Flynn maintains, in precisely the mortgages he was worried about: the 10-year loans obtained before the financial crisis. What Flynn discovered, he said, was that rather than lowering the values for properties that had taken on bigger loans than they could pay off, their owners instead obtained new loans. “Someone should have taken the losses,” he said. “Instead, they papered over it, inflated the cash flow and sold it on.”

For commercial borrowers, small bumps in a property’s profits can qualify the borrower for millions more in loans. Shaving expenses by about a third to boost profit, for instance, can sometimes allow a borrower to increase a loan’s size by a third as well — even if the expenses run only in the thousands, and the loan runs in the millions.

Some executives for lenders acknowledged to ProPublica that they made changes to borrowers’ past financials — scrubbing expenses from prior years they deemed irrelevant for the new loan — but maintained that it is appropriate to do so. Accounting firms review financial data before the loans are assembled into CMBS, they added.

The financial data that ProPublica examined — a sample of six loans among the thousands Flynn identified as having inflated net operating income — revealed potential weaknesses not readily apparent to the average investor. For those six loans, the profits for a given year were listed as 9% to 30% higher in new securities than in the old. After they were issued, half of those loans ended up on watch lists for problem debt, meaning the properties were considered at heightened risk for default.

In each of the six loans, the profit inflation seemed to be explained by decreases in the costs reported. Expenses reported for a particular year in one CMBS simply vanished in disclosures for the same year in a new CMBS.

Such a pattern appeared in a $36.7 million loan by Ladder Capital in 2015 to a team that purchased the Doubletree San Diego, a half-century-old hotel that struggled for years to bring in enough income to satisfy loan servicers, even under a previous, smaller loan.

The hotel’s new loan saddled it with far greater debt, increasing its main loan by 60% — even though the property had landed on a watchlist in 2010 because of declining revenue. Analysts at Moody’s pegged the hotel’s new loan as exceeding the value of the property by 40.5% (meaning a loan-to-value ratio of 140.5%).

Filings for the new loan claimed much higher profits than what the old loan had cited for the same years: The hotel’s net operating income for two years magically jumped from what had previously been reported: 21% and 16% larger for 2013 and 2014, respectively.

Such figures are supposed to be pulled from a property’s “most recent operating statement,” according to the regulation governing CMBS disclosures.

But, in response to questions from ProPublica, lender Ladder Capital said it altered the expense numbers it provided in the Doubletree’s historical financials. Ladder said it wiped lease payments —$700,608 and $592,823 in those two years — from the historical financials, because the new owner would not make lease payments in the future. (The previous owner had leased the building from an affiliated company.)

Ladder, a publicly traded commercial real estate investment trust that reports more than $6 billion in assets, said in a statement, “These differences are due to items that were considered by Ladder Capital during the due diligence process and reported appropriately in all relevant disclosures.”

Yet when ProPublica asked Ladder to share its disclosures about the changes, the firm pointed to a section of the pool’s prospectus that didn’t mention lease payments, or explain or acknowledge the change in income.

The Doubletree did not fare well under its new debt package. Revenues and occupancy declined after 2015 and by 2017, the hotel’s loan was back on the watch list. The hotel missed franchise fee payments. Ladder foreclosed in December 2019, after problems with an additional $5.8 million loan the lender had extended the property.

The Doubletree loan was not the only loan in its CMBS pool, issued by Deutsche Bank in 2015, with apparently inflated profits. Flynn said he was able to track down previous loan information for loans representing nearly 40% of the pool, and all had inflated income figures at some point in their historical financial data.

There was also a noticeable profit increase in two loans Ladder issued for a strip mall in suburban Pennsylvania. The mall’s past results improved when they appeared in a new CMBS. Its 2016 net operating income, previously listed as $1,101,207 in one CMBS, now appeared as $1,352,353 in another, data from Trepp shows — an increase of 23%. The prospectus for the latter does not explain or acknowledge the change in income. The mall owner received a $14 million loan.

Less than a year after it was placed into a CMBS, the loan ran into trouble. It landed on a watchlist after one of its major tenants, a department store, declared bankruptcy.

Ladder said it excluded $203,787 in expenses from the new loan because they stemmed from one-time costs for environmental remediation of pollution by a dry cleaner and a roof repair. Ladder did not explain why the previous lender did not exclude the expense also.

The pattern can be seen in loans made by other lenders, too. In a CMBS issued by Wells Fargo, a 1950s-era trailer park at the base of a steep bluff along the coast in Los Angeles reported sharply higher profits — for the same years — than it previously had.

The Pacific Palisades Bowl Park received a $12.9 million loan from the bank in 2016. The park reported expenses that were about a third lower in its new loan disclosures when compared with earlier ones. As a result, the $1.2 million in net operating income for 2014 rose 28% above what had been reported for the same year under the old loan. A similar jump occurred in 2013. (Edward Biggs, the owner of the park, said he gave Wells Fargo the park’s financials when refinancing its loan and wasn’t aware of discrepancies in what was reported to investors. “I don’t know anything about that,” he said.)

Flynn said he found that for the $575 million Wells Fargo CMBS that contained the Palisades debt, about half of the loan pool appeared to have reported inflated profits at some point, when comparing the same years in different securities.

Another of the loans ProPublica examined with apparently inflated profits was for a building in downtown Philadelphia. When the owner refinanced through Wells Fargo, the property’s 2015 profit appeared 23% higher than it had in reports under the old loan. Wells bundled the debt into a mortgage-backed security in 2016.

The building, One Penn Center, is a historic Art Deco office high-rise with ornate black marble and gold-plated fixtures, and a transit station underneath. One of the primary tenants, leasing 45,000 square feet for one of its regional headquarters, happens to be the SEC. The agency declined to comment.

Coronavirus, ‘Plandemic’ and the seven traits of conspiratorial thinking

May 16, 2020 The Conversation

The conspiracy theory video “Plandemic” recently went viral. Despite being taken down by YouTube and Facebook, it continues to get uploaded and viewed millions of times. The video is an interview with conspiracy theorist Judy Mikovits, a disgraced former virology researcher who believes the COVID-19 pandemic is based on vast deception, with the purpose of profiting from selling vaccinations.

The video is rife with misinformation and conspiracy theories. Many high-quality fact-checks and debunkings have been published by reputable outlets such as Science, Politifact and FactCheck.

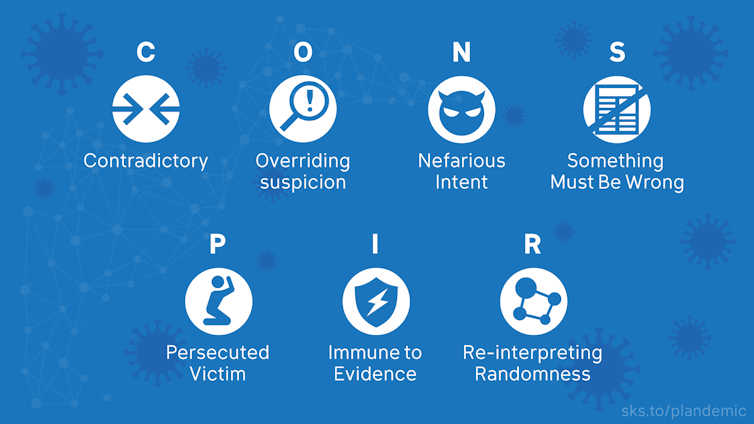

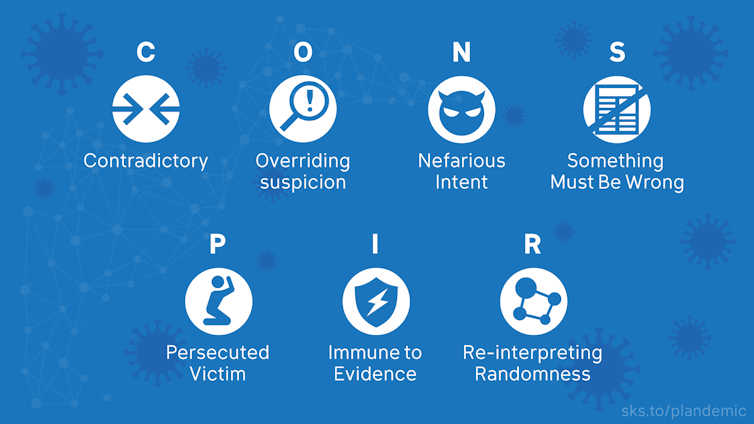

As scholars who research how to counter science misinformation and conspiracy theories, we believe there is also value in exposing the rhetorical techniques used in “Plandemic.” As we outline in our Conspiracy Theory Handbook and How to Spot COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories, there are seven distinctive traits of conspiratorial thinking. “Plandemic” offers textbook examples of them all

Learning these traits can help you spot the red flags of a baseless conspiracy theory and hopefully build up some resistance to being taken in by this kind of thinking. This is an important skill given the current surge of pandemic-fueled conspiracy theories.

4. Conviction something’s wrong

Conspiracy theorists may occasionally abandon specific ideas when they become untenable. But those revisions tend not to change their overall conclusion that “something must be wrong” and that the official account is based on deception.

When “Plandemic” filmmaker Mikki Willis was asked if he really believed COVID-19 was intentionally started for profit, his response was “I don’t know, to be clear, if it’s an intentional or naturally occurring situation. I have no idea.”

He has no idea. All he knows for sure is something must be wrong: “It’s too fishy.”

5. Persecuted victim

Conspiracy theorists think of themselves as the victims of organized persecution. “Plandemic” further ratchets up the persecuted victimhood by characterizing the entire world population as victims of a vast deception, which is disseminated by the media and even ourselves as unwitting accomplices.

At the same time, conspiracy theorists see themselves as brave heroes taking on the villainous conspirators.

6. Immunity to evidence

It’s so hard to change a conspiracy theorist’s mind because their theories are self-sealing. Even absence of evidence for a theory becomes evidence for the theory: The reason there’s no proof of the conspiracy is because the conspirators did such a good job covering it up.

7. Reinterpreting randomness

Conspiracy theorists see patterns everywhere – they’re all about connecting the dots. Random events are reinterpreted as being caused by the conspiracy and woven into a broader, interconnected pattern. Any connections are imbued with sinister meaning.

For example, the “Plandemic” video suggestively points to the U.S. National Institutes of Health funding that has gone to the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China. This is despite the fact that the lab is just one of many international collaborators on a project that sought to examine the risk of future viruses emerging from wildlife.Learning about common traits of conspiratorial thinking can help you recognize and resist conspiracy theories.

Critical thinking is the antidote

As we explore in our Conspiracy Theory Handbook, there are a variety of strategies you can use in response to conspiracy theories.

One approach is to inoculate yourself and your social networks by identifying and calling out the traits of conspiratorial thinking. Another approach is to “cognitively empower” people, by encouraging them to think analytically. The antidote to conspiratorial thinking is critical thinking, which involves healthy skepticism of official accounts while carefully considering available evidence.

Understanding and revealing the techniques of conspiracy theorists is key to inoculating yourself and others from being misled, especially when we are most vulnerable: in times of crises and uncertainty.

John Cook, Research Assistant Professor, Center for Climate Change Communication, George Mason University; Sander van der Linden, Director, Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, University of Cambridge; Stephan Lewandowsky, Chair of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol, and Ullrich Ecker, Associate Professor of Cognitive Science, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

May 16, 2020 The Conversation

The conspiracy theory video “Plandemic” recently went viral. Despite being taken down by YouTube and Facebook, it continues to get uploaded and viewed millions of times. The video is an interview with conspiracy theorist Judy Mikovits, a disgraced former virology researcher who believes the COVID-19 pandemic is based on vast deception, with the purpose of profiting from selling vaccinations.

The video is rife with misinformation and conspiracy theories. Many high-quality fact-checks and debunkings have been published by reputable outlets such as Science, Politifact and FactCheck.

As scholars who research how to counter science misinformation and conspiracy theories, we believe there is also value in exposing the rhetorical techniques used in “Plandemic.” As we outline in our Conspiracy Theory Handbook and How to Spot COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories, there are seven distinctive traits of conspiratorial thinking. “Plandemic” offers textbook examples of them all

Learning these traits can help you spot the red flags of a baseless conspiracy theory and hopefully build up some resistance to being taken in by this kind of thinking. This is an important skill given the current surge of pandemic-fueled conspiracy theories.

The seven traits of conspiratorial thinking.

John Cook, CC BY-ND

John Cook, CC BY-ND

1. Contradictory beliefs

Conspiracy theorists are so committed to disbelieving an official account, it doesn’t matter if their belief system is internally contradictory. The “Plandemic” video advances two false origin stories for the coronavirus. It argues that SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab in Wuhan – but also argues that everybody already has the coronavirus from previous vaccinations, and wearing masks activates it. Believing both causes is mutually inconsistent.

Conspiracy theorists are so committed to disbelieving an official account, it doesn’t matter if their belief system is internally contradictory. The “Plandemic” video advances two false origin stories for the coronavirus. It argues that SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab in Wuhan – but also argues that everybody already has the coronavirus from previous vaccinations, and wearing masks activates it. Believing both causes is mutually inconsistent.

2. Overriding suspicion

Conspiracy theorists are overwhelmingly suspicious toward the official account. That means any scientific evidence that doesn’t fit into the conspiracy theory must be faked.

But if you think the scientific data is faked, that leads down the rabbit hole of believing that any scientific organization publishing or endorsing research consistent with the “official account” must be in on the conspiracy. For COVID-19, this includes the World Health Organization, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, Anthony Fauci… basically, any group or person who actually knows anything about science must be part of the conspiracy.

Conspiracy theorists are overwhelmingly suspicious toward the official account. That means any scientific evidence that doesn’t fit into the conspiracy theory must be faked.

But if you think the scientific data is faked, that leads down the rabbit hole of believing that any scientific organization publishing or endorsing research consistent with the “official account” must be in on the conspiracy. For COVID-19, this includes the World Health Organization, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, Anthony Fauci… basically, any group or person who actually knows anything about science must be part of the conspiracy.

3. Nefarious intent

In a conspiracy theory, the conspirators are assumed to have evil motives. In the case of “Plandemic,” there’s no limit to the nefarious intent. The video suggests scientists including Anthony Fauci engineered the COVID-19 pandemic, a plot which involves killing hundreds of thousands of people so far for potentially billions of dollars of profit.

In a conspiracy theory, the conspirators are assumed to have evil motives. In the case of “Plandemic,” there’s no limit to the nefarious intent. The video suggests scientists including Anthony Fauci engineered the COVID-19 pandemic, a plot which involves killing hundreds of thousands of people so far for potentially billions of dollars of profit.

Conspiratorial thinking finds evil intentions at all levels of the presumed conspiracy.

4. Conviction something’s wrong

Conspiracy theorists may occasionally abandon specific ideas when they become untenable. But those revisions tend not to change their overall conclusion that “something must be wrong” and that the official account is based on deception.

When “Plandemic” filmmaker Mikki Willis was asked if he really believed COVID-19 was intentionally started for profit, his response was “I don’t know, to be clear, if it’s an intentional or naturally occurring situation. I have no idea.”

He has no idea. All he knows for sure is something must be wrong: “It’s too fishy.”

5. Persecuted victim

Conspiracy theorists think of themselves as the victims of organized persecution. “Plandemic” further ratchets up the persecuted victimhood by characterizing the entire world population as victims of a vast deception, which is disseminated by the media and even ourselves as unwitting accomplices.

At the same time, conspiracy theorists see themselves as brave heroes taking on the villainous conspirators.

6. Immunity to evidence

It’s so hard to change a conspiracy theorist’s mind because their theories are self-sealing. Even absence of evidence for a theory becomes evidence for the theory: The reason there’s no proof of the conspiracy is because the conspirators did such a good job covering it up.

7. Reinterpreting randomness

Conspiracy theorists see patterns everywhere – they’re all about connecting the dots. Random events are reinterpreted as being caused by the conspiracy and woven into a broader, interconnected pattern. Any connections are imbued with sinister meaning.

For example, the “Plandemic” video suggestively points to the U.S. National Institutes of Health funding that has gone to the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China. This is despite the fact that the lab is just one of many international collaborators on a project that sought to examine the risk of future viruses emerging from wildlife.Learning about common traits of conspiratorial thinking can help you recognize and resist conspiracy theories.

Critical thinking is the antidote

As we explore in our Conspiracy Theory Handbook, there are a variety of strategies you can use in response to conspiracy theories.

One approach is to inoculate yourself and your social networks by identifying and calling out the traits of conspiratorial thinking. Another approach is to “cognitively empower” people, by encouraging them to think analytically. The antidote to conspiratorial thinking is critical thinking, which involves healthy skepticism of official accounts while carefully considering available evidence.

Understanding and revealing the techniques of conspiracy theorists is key to inoculating yourself and others from being misled, especially when we are most vulnerable: in times of crises and uncertainty.

John Cook, Research Assistant Professor, Center for Climate Change Communication, George Mason University; Sander van der Linden, Director, Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, University of Cambridge; Stephan Lewandowsky, Chair of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol, and Ullrich Ecker, Associate Professor of Cognitive Science, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

#OBAMAGATE

It’s not just a chant at Trump’s rallies or lame wordplay in his tweets — it’s his call to fascist rule

Published May 16, 2020 By Lucian K. Truscott IV, Salon

You know someone’s in a real panic when they start running in circles, and that’s what Donald Trump has been doing for the past week. He started off last Sunday with an epic tweetstorm, 126 of them in all, the third-highest total for one day in his presidency, according to FactBa.se, which keeps track of Trump’s statements. “Obamagate!” he tweeted, following that one with “Because it was Obamagate, and he and Sleepy Joe led the charge. The most corrupt administration in history!”

That presaged by 24 hours his now-famous exchange with Philip Rucker of the Washington Post in the Rose Garden, when Rucker asked him, “What crime, exactly, are you accusing President Obama of committing?”

“Obamagate,” Trump replied, refusing to define the “crime” or provide any specific evidence. So Rucker followed up: “What is the crime, exactly, that you’re accusing him of?” Trump shot him what passed for an angry look: “You know what the crime is,” Trump answered. “The crime is very obvious to everybody.”

What was Obamagate, pundits asked each other with puzzled looks on their faces, as the week wore on? They should have known that it would have something to do with Michael Flynn, Trump’s former national security adviser, who lasted all of 24 days in the job before being fired for lying to Vice President Mike Pence about his phone call with Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak in late December of 2016. Flynn was later charged with lying to the FBI, pled guilty twice, and has been awaiting sentencing for more than two years. Trump’s Department of Justice, under the direction of Large Lickspittle Bill Barr, moved to drop the charges against Flynn last week, which generated a letter signed by 2,000 former Justice Department officials denouncing the motion filed by Little Lickspittle Timothy Shea, the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia. The judge in the case will hold hearings on the matter and has not yet issued a ruling.

There is a perfect symmetry to the involvement of Michael Flynn in Trump’s latest attempt to deflect attention from his inept handling of the coronavirus crisis, which has caused the infections of more than 1.4 million Americans and the deaths of more than 87,000 nationwide. Flynn enjoyed a singular distinction during the transition between the Obama and Trump administrations, besides his coziness with Russian bankers and ambassadors. Obama gave Trump only one piece of personal advice during their private meeting in the White House after Trump was elected: Whatever you do, don’t hire Michael Flynn. For anything. Ever.

But Trump loved Flynn. It had been Flynn who led the delegates at the 2016 Republican National Convention in chanting “lock her up” after mentioning the alleged criminal behavior of Hillary Clinton as secretary of state. As with Trump’s use of “Obamagate” as a shorthand for Obama’s alleged corruption while in office, Flynn’s allegations against Clinton were equally vague and shorn of specificity. Trump had already been encouraging his crowds to chant “lock her up” at his campaign rallies in 2016, and has continued the practice ever since. I don’t know of a single rally Trump has held since he’s been in office when the crowd didn’t break into the “lock her up” chant, with Trump allowing the fascist bellowing to wash over him as he stands at the podium, smiling with approval at the crowd.

I use the words “fascist bellowing” on purpose, because that’s what it is: Trump supporters at public events and rallies loudly endorsing official lawlessness. It’s not a funny joke or clever verbiage. Trump and his followers have been routinely advocating the jailing of Trump’s political opponents without an investigation, criminal charges, trial or conviction by a jury of their peers. This is the way fascist dictators dispose of their political opposition. Putin has jailed opponents of his regime. He has also arrested wealthy businessmen whose enterprises he wanted to seize, and of course he has ordered the murder of Russian citizens who he felt betrayed him.

Trump himself circled back around to calling for the jailing of his political enemies for unspecified crimes on Thursday morning in an interview with Maria Bartiromo on the Fox Business Network. Trump called the “unmasking” of Flynn “the greatest political crime in the history of our country.”

He continued: “If I were a Democrat instead of a Republican, I think everybody would have been in jail a long time ago … it is a disgrace what’s happened. This is the greatest political scam, hoax in the history of our country.” To set the record straight, that’s ludicrous and untrue. Flynn’s “unmasking” was a routine national security procedure during which officials in the Obama administration were given Flynn’s name as the person who was caught on NSA wiretaps talking to Kislyak during the Trump transition, when Flynn was serving as an adviser to Trump on national security and international relations. Included among the Obama officials were Trump’s bete noire, former FBI director James Comey, and Vice President Joe Biden.

Another fascist dictator who made use of extrajudicial imprisonment of political enemies was Adolf Hitler. He didn’t bother with leading “Lock her up” chants at his rallies. He just locked up his political opponents and racial and ethnic and religious enemies in concentration camps where they were executed or perished from disease and starvation. His followers rewarded him at political rallies by chanting “Heil Hitler.” It was the all-purpose approbation of Hitler’s leadership of Nazi Germany, a mass public endorsement of everything he did, including locking up his political opponents. That’s what “Lock her up” has become for Trump.

Trump’s campaign people are already talking about holding rallies as Trump blackmails the states by pushing his “open up” madness. “Lock her up” chant doubles down on hatred for Hillary Clinton, or these days for Nancy Pelosi and Joe Biden, for those in love with Trump, by loudly calling for his political opponents to be imprisoned without trial for unspecified crimes. If you don’t believe me, listen to the chant the next time he holds a rally. Trump’s followers are both swearing allegiance and saluting him. “Lock her up” is Trump’s “Heil Hitler.”

It’s not just a chant at Trump’s rallies or lame wordplay in his tweets — it’s his call to fascist rule

Published May 16, 2020 By Lucian K. Truscott IV, Salon

You know someone’s in a real panic when they start running in circles, and that’s what Donald Trump has been doing for the past week. He started off last Sunday with an epic tweetstorm, 126 of them in all, the third-highest total for one day in his presidency, according to FactBa.se, which keeps track of Trump’s statements. “Obamagate!” he tweeted, following that one with “Because it was Obamagate, and he and Sleepy Joe led the charge. The most corrupt administration in history!”

That presaged by 24 hours his now-famous exchange with Philip Rucker of the Washington Post in the Rose Garden, when Rucker asked him, “What crime, exactly, are you accusing President Obama of committing?”

“Obamagate,” Trump replied, refusing to define the “crime” or provide any specific evidence. So Rucker followed up: “What is the crime, exactly, that you’re accusing him of?” Trump shot him what passed for an angry look: “You know what the crime is,” Trump answered. “The crime is very obvious to everybody.”

What was Obamagate, pundits asked each other with puzzled looks on their faces, as the week wore on? They should have known that it would have something to do with Michael Flynn, Trump’s former national security adviser, who lasted all of 24 days in the job before being fired for lying to Vice President Mike Pence about his phone call with Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak in late December of 2016. Flynn was later charged with lying to the FBI, pled guilty twice, and has been awaiting sentencing for more than two years. Trump’s Department of Justice, under the direction of Large Lickspittle Bill Barr, moved to drop the charges against Flynn last week, which generated a letter signed by 2,000 former Justice Department officials denouncing the motion filed by Little Lickspittle Timothy Shea, the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia. The judge in the case will hold hearings on the matter and has not yet issued a ruling.

There is a perfect symmetry to the involvement of Michael Flynn in Trump’s latest attempt to deflect attention from his inept handling of the coronavirus crisis, which has caused the infections of more than 1.4 million Americans and the deaths of more than 87,000 nationwide. Flynn enjoyed a singular distinction during the transition between the Obama and Trump administrations, besides his coziness with Russian bankers and ambassadors. Obama gave Trump only one piece of personal advice during their private meeting in the White House after Trump was elected: Whatever you do, don’t hire Michael Flynn. For anything. Ever.

But Trump loved Flynn. It had been Flynn who led the delegates at the 2016 Republican National Convention in chanting “lock her up” after mentioning the alleged criminal behavior of Hillary Clinton as secretary of state. As with Trump’s use of “Obamagate” as a shorthand for Obama’s alleged corruption while in office, Flynn’s allegations against Clinton were equally vague and shorn of specificity. Trump had already been encouraging his crowds to chant “lock her up” at his campaign rallies in 2016, and has continued the practice ever since. I don’t know of a single rally Trump has held since he’s been in office when the crowd didn’t break into the “lock her up” chant, with Trump allowing the fascist bellowing to wash over him as he stands at the podium, smiling with approval at the crowd.

I use the words “fascist bellowing” on purpose, because that’s what it is: Trump supporters at public events and rallies loudly endorsing official lawlessness. It’s not a funny joke or clever verbiage. Trump and his followers have been routinely advocating the jailing of Trump’s political opponents without an investigation, criminal charges, trial or conviction by a jury of their peers. This is the way fascist dictators dispose of their political opposition. Putin has jailed opponents of his regime. He has also arrested wealthy businessmen whose enterprises he wanted to seize, and of course he has ordered the murder of Russian citizens who he felt betrayed him.