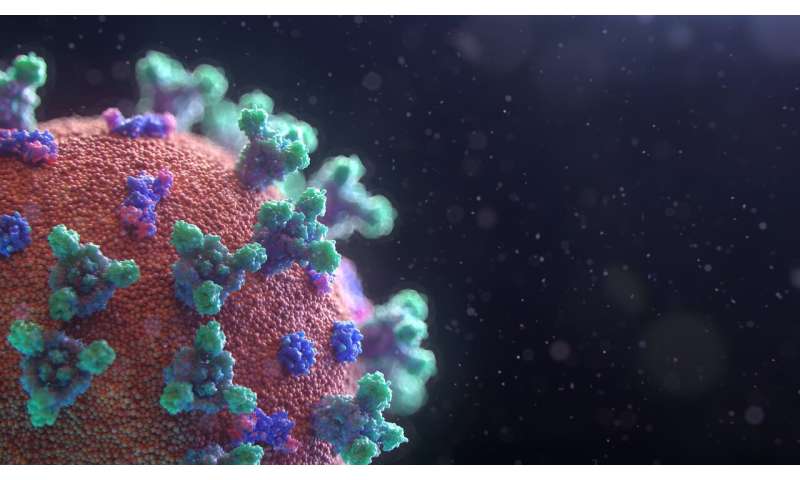

Virus DNA spread across surfaces in hospital ward over 10 hours

Virus DNA left on a hospital bed rail was found in nearly half of all sites sampled across a ward within 10 hours and persisted for at least five days, according to a new study by UCL and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH).

The study, published as a letter in the Journal of Hospital Infection, aimed to safely simulate how SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, may spread across surfaces in a hospital.

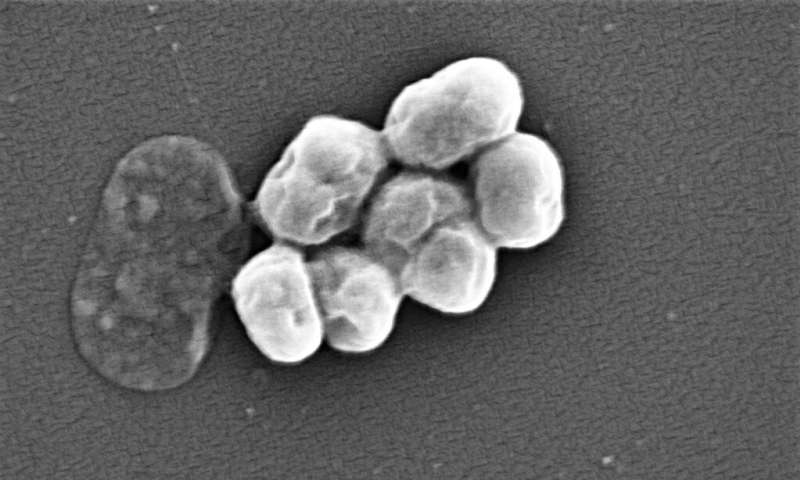

Instead of using the SARS-CoV-2 virus, researchers artificially replicated a section of DNA from a plant-infecting virus, which cannot infect humans, and added it to a milliliter of water at a similar concentration to SARS-CoV-2 copies found in infected patients' respiratory samples.

Researchers placed the water containing this DNA on the hand rail of a hospital bed in an isolation room—that is, a room for higher-risk or infected patients—and then sampled 44 sites across a hospital ward over the following five days.

They found that after 10 hours, the surrogate genetic material had spread to 41% of sites sampled across the hospital ward, from bed rails to door handles to arm rests in a waiting room to children's toys and books in a play area. This increased to 59% of sites after three days, falling to 41% on the fifth day.

Dr. Lena Ciric (UCL Civil, Environmental & Geomatic Engineering), a senior author of the study, said: "Our study shows the important role that surfaces play in the transmission of a virus and how critical it is to adhere to good hand hygiene and cleaning.

"Our surrogate was inoculated once to a single site, and was spread through the touching of surfaces by staff, patients and visitors. A person with SARS-CoV-2, though, will shed the virus on more than one site, through coughing, sneezing and touching surfaces."

The highest proportion of sites that tested positive for the surrogate came from the immediate bedspace area—including a nearby room with several other beds—and clinical areas such as treatment rooms. On day three, 86% of sampled sites in clinical areas tested positive, while on day four, 60% of sampled sites in the immediate bedspace area tested positive.

Co-author Dr. Elaine Cloutman-Green (UCL Civil, Environmental & Geomatic Engineering), Lead Healthcare Scientist at GOSH, said: "People can become infected with Covid-19 through respiratory droplets produced during coughing or sneezing. Equally, if these droplets land on a surface, a person may become infected after coming into contact with the surface and then touching their eyes, nose or mouth.

"Like SARS-CoV-2, the surrogate we used for the study could be removed with a disinfectant wipe or by washing hands with soap and water. Cleaning and handwashing represent our first line of defense against the virus and this study is a significant reminder that healthcare workers and all visitors to a clinical setting can help stop its spread through strict hand hygiene, cleaning of surfaces, and proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE)."

SARS-CoV-2 will likely be spread within bodily fluid such as cough droplets, whereas the study used virus DNA in water. More sticky fluid such as mucus would likely spread more easily.

One caveat to the study is that, while it shows how quickly a virus can spread if left on a surface, it cannot determine how likely it is that a person would be infectedFollow the latest news on the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak

More information: S. Rawlinson et al, COVID-19 pandemic – let's not forget surfaces, Journal of Hospital Infection (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.05.022

Provided by University College London