Study finds our visual world of color is largely incorrect

Color awareness has long been a puzzle for researchers in neuroscience and psychology, who debate over how much color observers really perceive. A study from Dartmouth in collaboration with Amherst College finds that people are aware of surprisingly limited color in their peripheral vision; much of our sense of a colorful visual world is likely constructed by our brain. The findings are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

To test people's visual awareness of color during naturalistic viewing, the researchers used head-mounted virtual reality displays installed with eye-trackers to immerse participants in a 360-degree real-world environment. The virtual environments included tours of historic sites, a street dance performance, a symphony rehearsal and more, where observers could explore their surroundings simply by turning their heads. With the eye-tracking tool, researchers knew exactly where an observer was looking at all times in the scene and could make systematic changes to the visual environment so that only the areas where the person was looking were in color. The rest of the scene in the periphery was desaturated so that it had no color and was just in black and white. After a series of trials, observers were asked a series of questions to gauge if they noticed the lack of color in their periphery. A supplemental video from the study illustrates how the peripheral color was removed from various scenes.

To test people's visual awareness of color during naturalistic viewing, the researchers used head-mounted virtual reality displays installed with eye-trackers to immerse participants in a 360-degree real-world environment. The virtual environments included tours of historic sites, a street dance performance, a symphony rehearsal and more, where observers could explore their surroundings simply by turning their heads. With the eye-tracking tool, researchers knew exactly where an observer was looking at all times in the scene and could make systematic changes to the visual environment so that only the areas where the person was looking were in color. The rest of the scene in the periphery was desaturated so that it had no color and was just in black and white. After a series of trials, observers were asked a series of questions to gauge if they noticed the lack of color in their periphery. A supplemental video from the study illustrates how the peripheral color was removed from various scenes.

In your visual field, your periphery extends approximately 210 degrees, which is similar to if your arms are stretched out on your left and right. The study's results showed that most people's color awareness is limited to a small area around the dead center of their visual field. When the researchers removed most color in the periphery, most people did not notice. In the most extreme case, almost a third of observers did not notice when less than five percent of the entire visual field was presented in color (radius of 10 degrees visual angle).

1.125rem;">

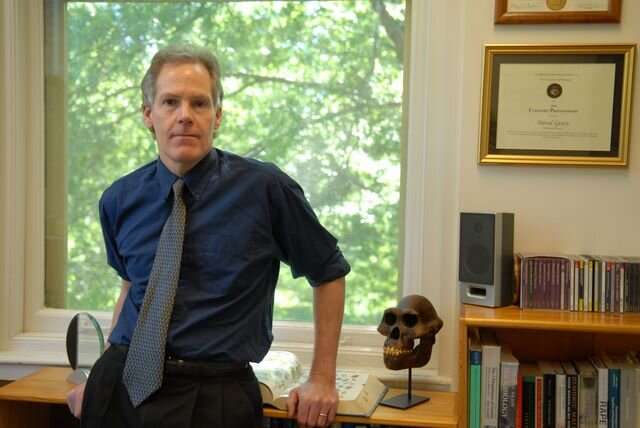

Credit: Dartmouth College

Participants were astonished to find out later that they hadn't noticed the desaturated periphery, after they were shown the changes that were made to a virtual scene that they had just explored.

A second study tasked the participants to identify when color was desaturated in the periphery. The results were similar in that most people failed to notice when the peripheral color had been removed. A large number of people participated in the two studies, which featured nearly 180 participants in total.

"We were amazed by how oblivious participants were when color was removed from up to 95 percent of their visual world," said senior author, Caroline Robertson, an assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth. "Our results show that our intuitive sense of a rich, colorful visual world is largely incorrect. Our brain is likely filling-in much of our perceptual experience."

Previous studies evaluating the limitations of visual awareness often relied on participants staring at video content on computer screens directly in front of them. By leveraging the virtual reality experience, this research approach is novel, as the 360-degree environment is more similar to the way people experience the real-world.Which areas of our brains represent the colors we see?

More information: Michael A. Cohen el al., "The limits of color awareness during active, real-world vision," PNAS (2020). www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1922294117

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences