Study on shorebirds suggests that when conserving species, not all land is equal

by Princeton University

Princeton researchers may have solved the long-standing puzzle of why migratory shorebirds around the world are plummeting several times faster than coastal ecosystems are being developed. They discovered that shorebirds overwhelmingly rely on the portion of tidal zones closest to dry land for food and rest as they migrate, which are the locations most often lost to development. The findings stress the need for integrating upper tidal flats into conservation plans focused on migratory shorebirds. Credit: Tong Mu, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Princeton University researchers may have solved a long-standing mystery in conservation that could influence how natural lands are designated for the preservation of endangered species.

Around the world, the migratory shorebirds that are a conspicuous feature of coastal habitats are losing access to the tidal flats—the areas between dry land and the sea—they rely on for food as they travel and prepare to breed. But a major puzzle has been that species' populations are plummeting several times faster than the rate at which coastal ecosystems are lost to development.

Nowhere is the loss of tidal flats and shorebird species more acute than along the East Asia-Australasian Flyway (EAAF). An estimated 5 million migratory birds from 55 species use the flyway to travel from southern Australia to northern Siberia along the rapidly developing coast of China—where tidal flats can be more than 6 miles wide—at which birds stop to rest and refuel.

Since the 1980s, the loss of tidal flats around the Yellow Sea has averaged 1.2% per year. Yet, the annual loss of the most endangered bird species has averaged between 5.1 and 7.5%, with populations of species such as the critically endangered spoon-billed sandpipers (Calidris pygmaea) climbing as high as 26% each year.

In exploring this disparity, Princeton researchers Tong Mu and David Wilcove found a possible answer—the birds don't use all parts of the tidal flat equally. They discovered that migratory shorebirds overwhelmingly rely on the upper tidal flats closest to dry land, which are the exact locations most often lost to development.

They report in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B that China's upper tidal flats provided more than 70% of the cumulative foraging time for the species they studied at two Yellow Sea sites along the EAAF. The middle and lower flats that birds are increasingly pushed toward by human activity were less frequently foraged upon due to the tide cycle, which may be impacting species health and breeding success.

The findings stress the need for integrating upper tidal flats into conservation plans focused on migratory shorebirds, the authors reported.

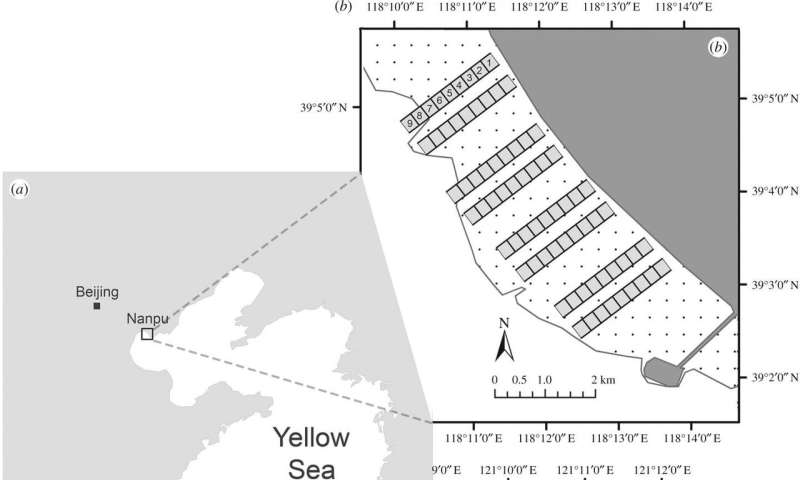

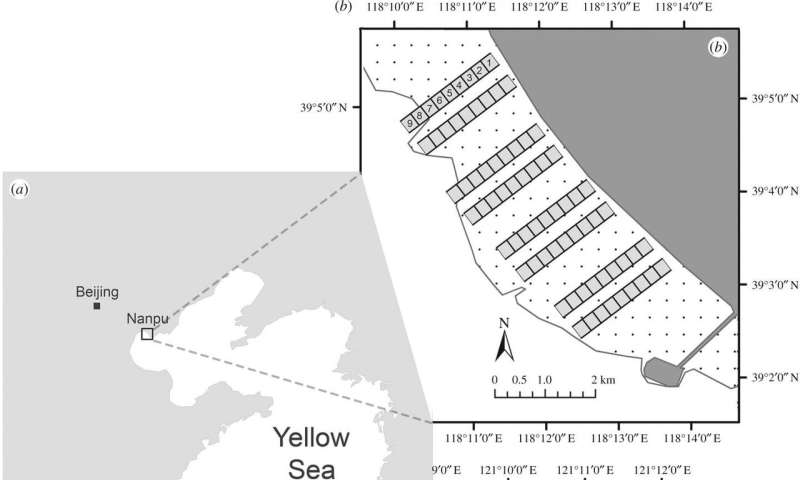

A key difference of the Princeton research was that it included observations of the high-tide period when the middle and lower tidal flats are underwater. The researchers focused on the East Asia-Australasian Flyway, which spans from Australia to Siberia along the rapidly developing coast of China where birds stop to rest and refuel. The researchers studied birds at two well-known stopover sites in the Yellow Sea region, Nanpu (b) near Beijing and Rudong (c) outside of Shanghai. The dark squares indicate the study plots along the upper, middle and lower tidal flats (dotted area). The white areas represent the sea beyond the low-tide line. Credit: Tong Mu, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

A key difference of the Princeton research was that it included observations of the high-tide period when the middle and lower tidal flats are underwater. The researchers focused on the East Asia-Australasian Flyway, which spans from Australia to Siberia along the rapidly developing coast of China where birds stop to rest and refuel. The researchers studied birds at two well-known stopover sites in the Yellow Sea region, Nanpu (b) near Beijing and Rudong (c) outside of Shanghai. The dark squares indicate the study plots along the upper, middle and lower tidal flats (dotted area). The white areas represent the sea beyond the low-tide line. Credit: Tong Mu, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

"This is a new insight into Asian shorebirds, but I suspect that the upper intertidal is disproportionately important to shorebirds in other places, too, such as the East and West coasts of North America," said Wilcove, who is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI).

\

Princeton University researchers may have solved a long-standing mystery in conservation that could influence how natural lands are designated for the preservation of endangered species.

Around the world, the migratory shorebirds that are a conspicuous feature of coastal habitats are losing access to the tidal flats—the areas between dry land and the sea—they rely on for food as they travel and prepare to breed. But a major puzzle has been that species' populations are plummeting several times faster than the rate at which coastal ecosystems are lost to development.

Nowhere is the loss of tidal flats and shorebird species more acute than along the East Asia-Australasian Flyway (EAAF). An estimated 5 million migratory birds from 55 species use the flyway to travel from southern Australia to northern Siberia along the rapidly developing coast of China—where tidal flats can be more than 6 miles wide—at which birds stop to rest and refuel.

Since the 1980s, the loss of tidal flats around the Yellow Sea has averaged 1.2% per year. Yet, the annual loss of the most endangered bird species has averaged between 5.1 and 7.5%, with populations of species such as the critically endangered spoon-billed sandpipers (Calidris pygmaea) climbing as high as 26% each year.

In exploring this disparity, Princeton researchers Tong Mu and David Wilcove found a possible answer—the birds don't use all parts of the tidal flat equally. They discovered that migratory shorebirds overwhelmingly rely on the upper tidal flats closest to dry land, which are the exact locations most often lost to development.

They report in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B that China's upper tidal flats provided more than 70% of the cumulative foraging time for the species they studied at two Yellow Sea sites along the EAAF. The middle and lower flats that birds are increasingly pushed toward by human activity were less frequently foraged upon due to the tide cycle, which may be impacting species health and breeding success.

The findings stress the need for integrating upper tidal flats into conservation plans focused on migratory shorebirds, the authors reported.

A key difference of the Princeton research was that it included observations of the high-tide period when the middle and lower tidal flats are underwater. The researchers focused on the East Asia-Australasian Flyway, which spans from Australia to Siberia along the rapidly developing coast of China where birds stop to rest and refuel. The researchers studied birds at two well-known stopover sites in the Yellow Sea region, Nanpu (b) near Beijing and Rudong (c) outside of Shanghai. The dark squares indicate the study plots along the upper, middle and lower tidal flats (dotted area). The white areas represent the sea beyond the low-tide line. Credit: Tong Mu, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

A key difference of the Princeton research was that it included observations of the high-tide period when the middle and lower tidal flats are underwater. The researchers focused on the East Asia-Australasian Flyway, which spans from Australia to Siberia along the rapidly developing coast of China where birds stop to rest and refuel. The researchers studied birds at two well-known stopover sites in the Yellow Sea region, Nanpu (b) near Beijing and Rudong (c) outside of Shanghai. The dark squares indicate the study plots along the upper, middle and lower tidal flats (dotted area). The white areas represent the sea beyond the low-tide line. Credit: Tong Mu, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology"This is a new insight into Asian shorebirds, but I suspect that the upper intertidal is disproportionately important to shorebirds in other places, too, such as the East and West coasts of North America," said Wilcove, who is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI).

\

"People start at the upper zone and work their way outward, so the best spots for the birds are the first to go," he said. "It would probably be best to extend current developments farther into the intertidal zone rather than keep building parallel to the coast, which consumes more of the upper intertidal.

"Think of it as advocating for a rectangle with the long side pointing into the sea versus a rectangle with the long side hugging the shore," Wilcove said.

The study results also suggest that protecting species and their habitats may mean more than designating land for wildlife—it may require identifying the right land to set aside by gaining a detailed understanding of exactly how animals interact with the landscape.

"Recognizing the importance of a kind of habitat to specific species or groups of species takes time, effort and thought," said Mu, who is the paper's first author and a Ph.D. candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology.

"Sometimes we just don't know what to look for, or looking requires challenging some prevalent and maybe false perceptions," he said. "But the situation is getting better and better. People are paying more attention to environmental issues, and the advances in technology are helping us gain more and newer insight into these questions."

Mu conducted fieldwork between September 2016 and May 2017 at two well-known stopover sites—one outside of Beijing, the other near Shanghai—for migratory shorebirds in the Yellow Sea region. He focused on 17 species of birds, noting where along the tidal flat the animals preferred to feed.

"Think of it as advocating for a rectangle with the long side pointing into the sea versus a rectangle with the long side hugging the shore," Wilcove said.

The study results also suggest that protecting species and their habitats may mean more than designating land for wildlife—it may require identifying the right land to set aside by gaining a detailed understanding of exactly how animals interact with the landscape.

"Recognizing the importance of a kind of habitat to specific species or groups of species takes time, effort and thought," said Mu, who is the paper's first author and a Ph.D. candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology.

"Sometimes we just don't know what to look for, or looking requires challenging some prevalent and maybe false perceptions," he said. "But the situation is getting better and better. People are paying more attention to environmental issues, and the advances in technology are helping us gain more and newer insight into these questions."

Mu conducted fieldwork between September 2016 and May 2017 at two well-known stopover sites—one outside of Beijing, the other near Shanghai—for migratory shorebirds in the Yellow Sea region. He focused on 17 species of birds, noting where along the tidal flat the animals preferred to feed.

The findings suggest that protecting species requires gaining a detailed understanding of exactly how animals interact with the landscape so that preserved habitats best serve endangered species' needs. Since the 1980s, the loss of tidal flats around the Yellow Sea has averaged 1.2% per year. Yet, the annual loss of the most endangered bird species has averaged between 5.1 and 7.5%, with populations of species such as the critically endangered spoon-billed sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea) climbing as high as 26% each year. Credit: Tong Mu, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

A key difference to his approach, Mu said, is that most previous research focused on the low-tide period when all the tidal flats are exposed and the full range of intertidal species can be observed.

"It makes sense from an ecological point of view. During the high tides when only a portion of the tidal flats is accessible, the relationship usually still holds for the exposed area," Mu said. "So, there's little incentive to look at the periods other than low tide when researchers can get a more complete picture."

What Mu thinks was missed, however, was that the upper tidal flats provide the most amount of foraging time for birds that have places to be. Even if the lower half of a 6-mile wide mudflat is set aside for migratory birds, they're not getting the energy they need for the trip ahead during the high tide, he said.

"The value of the tidal flats comes from not only their size, but also how much foraging time they can provide," Mu said. "The upper tidal area is exposed for a longer period during tidal cycles, compared to the middle and lower areas, which I think permits shorebirds to forage for a longer time and thus get more energy."

The preservation of shorebirds should be driven by how integral the animals are to the health of intertidal zones, Mu and Wilcove said. In turn, tidal flats are not only vital to other marine life, but also provide people with seafood such as clams and crabs and protection from storms and storm surges that cause coastal flooding.

"Shorebirds facilitate the energy and nutrient exchanges between land and sea," Mu said. "Because a lot of them are long-distance migrants, they also facilitate the energy and nutrient exchanges across different ecosystems and continents, something that is usually overlooked and underappreciated."

Wilcove and Mu cited recent research showing that more than 15%, or more than 12,000 square miles, of the world's natural tidal flats were lost between 1984-2016.

"Some of the greatest travelers on Earth are the shorebirds that migrate from Siberia to Southeast Asia and Australia," Wilcove said. "Now, they're declining in response to the loss of the tidal areas, and the full range of benefits those tidal flats provide are in some way being diminished."

Australia migratory bird levels plunge from Asia development

More information: Tong Mu et al, Upper tidal flats are disproportionately important for the conservation of migratory shorebirds, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2020). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2020.0278

Journal information: Proceedings of the Royal Society B

Provided by Princeton University

A key difference to his approach, Mu said, is that most previous research focused on the low-tide period when all the tidal flats are exposed and the full range of intertidal species can be observed.

"It makes sense from an ecological point of view. During the high tides when only a portion of the tidal flats is accessible, the relationship usually still holds for the exposed area," Mu said. "So, there's little incentive to look at the periods other than low tide when researchers can get a more complete picture."

What Mu thinks was missed, however, was that the upper tidal flats provide the most amount of foraging time for birds that have places to be. Even if the lower half of a 6-mile wide mudflat is set aside for migratory birds, they're not getting the energy they need for the trip ahead during the high tide, he said.

"The value of the tidal flats comes from not only their size, but also how much foraging time they can provide," Mu said. "The upper tidal area is exposed for a longer period during tidal cycles, compared to the middle and lower areas, which I think permits shorebirds to forage for a longer time and thus get more energy."

The preservation of shorebirds should be driven by how integral the animals are to the health of intertidal zones, Mu and Wilcove said. In turn, tidal flats are not only vital to other marine life, but also provide people with seafood such as clams and crabs and protection from storms and storm surges that cause coastal flooding.

"Shorebirds facilitate the energy and nutrient exchanges between land and sea," Mu said. "Because a lot of them are long-distance migrants, they also facilitate the energy and nutrient exchanges across different ecosystems and continents, something that is usually overlooked and underappreciated."

Wilcove and Mu cited recent research showing that more than 15%, or more than 12,000 square miles, of the world's natural tidal flats were lost between 1984-2016.

"Some of the greatest travelers on Earth are the shorebirds that migrate from Siberia to Southeast Asia and Australia," Wilcove said. "Now, they're declining in response to the loss of the tidal areas, and the full range of benefits those tidal flats provide are in some way being diminished."

Australia migratory bird levels plunge from Asia development

More information: Tong Mu et al, Upper tidal flats are disproportionately important for the conservation of migratory shorebirds, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2020). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2020.0278

Journal information: Proceedings of the Royal Society B

Provided by Princeton University