Amazon risks combusting with twin fire, virus crises

As tens of thousands of fires consumed the Amazon last year, it seemed the world's biggest rainforest could not be in greater peril.

But now fire season is here again, and the coronavirus pandemic risks making it even worse.

This year, experts say, the huge number of trees already felled in the rainforest could fuel more destructive fires.

Meanwhile, the smoke risks causing a new spike in respiratory emergencies in a region already overwhelmed with them because of coronavirus.

And there is a potentially vicious circle fueling these twin crises: the more the region is consumed by the pandemic, the less environmental authorities have staff and resources to protect the forest; but the more the forest burns, the worse the health crisis will get.

Last August, scenes of the Amazon burning triggered world outcry, as giant swathes of one of Earth's most vital resources sent a thick haze of black smoke all the way to Sao Paulo, thousands of kilometers away.

In a report published Monday, the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) warned that this year, fire season, which typically starts in June with dryer weather, could be far more devastating.

Amazon fires are caused mainly by illegal farmers and ranchers who clear land and torch the trees.

But last year, international scrutiny and Brazil's decision to deploy its army to the region forced many of them to forego the "burn" part of the slash-and-burn method, experts say.

"A deforested area of at least 4,500 square kilometers (1,750 square miles) in the Amazon, three times larger than the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil, is ready to burn," IPAM said.

Meanwhile, slashing has increased.

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon hit a record high of 1,843 square kilometers in the first five months of 2020, according to satellite data.

IPAM said the figure of 4,500 square kilometers would probably double by August.

"If only 60 percent of this estimated area burns, we will have a fire season in the region similar to that of 2019," it said.

"If 100 percent of this area burns, we will be able to witness an unprecedented health calamity in the Amazon region, when adding the effects of COVID-19."

Fuel to the fire

Last year's fires triggered international criticism of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right climate-change skeptic who wants to legalize logging, farming and mining on protected Amazon land.

Bolsonaro initially downplayed the fires as they ripped through the forest with the help of hot temperatures and a long dry season.

But eventually, he gave in to pressure and deployed the army to crack down on deforestation.

The strategy worked—in the short term.

"What I saw in lots of different areas where I work ... is that people just didn't burn. They left the forest on the ground. So then it brings another angle to the story, which is, when is this going to burn?" said Erika Berenguer, an Amazon ecologist at Oxford and Lancaster Universities.

"If it burns now ... we have respiratory illness due to smoke, and we have COVID," she told AFP.

Feedback loop

Brazil, which holds about 60 percent of the Amazon, is the latest epicenter of the pandemic, with the third-highest death toll worldwide.

The Amazon region has been hit hard, with overstretched hospitals and indigenous populations that are especially vulnerable to outside diseases.

Brazil's Amazonas state has just one intensive care unit to serve an area more than four times the size of Germany.

It has had to dig mass graves and store cadavers in refrigerator trucks to cope.

Meanwhile, coronavirus has reduced the authorities' capacity to stop record deforestation driven by illegal agriculture, logging and mining.

"The bad guys and land-grabbers aren't in quarantine while the good guys, police and government agents are fighting the virus," IPAM's director, Andre Guimaraes, told newspaper Globo.

The diversion may be deliberate.

Environment Minister Ricardo Salles was recorded in April saying the government should take advantage of the pandemic distraction to relax regulations.

Meanwhile, air pollution from fires could cause a critical new phase in Brazil's coronavirus crisis.

"This nefarious combination can result in an unprecedented burden on the already fragile and deficient health system in the Amazon," IPAM said.

© 2020 A

]

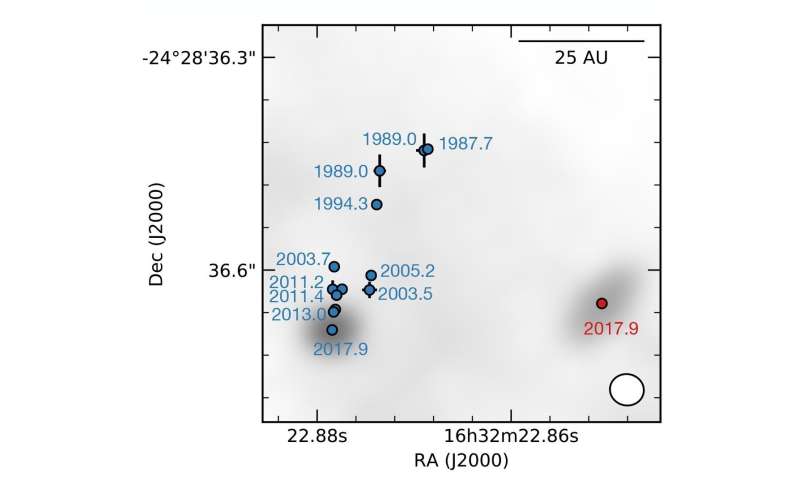

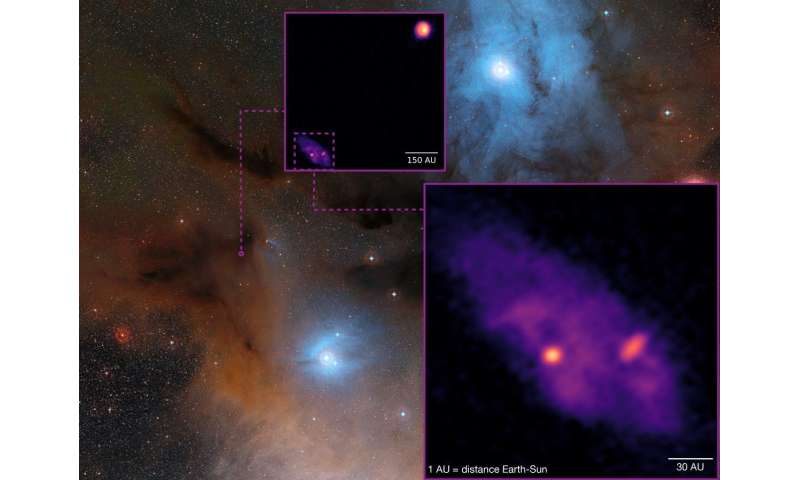

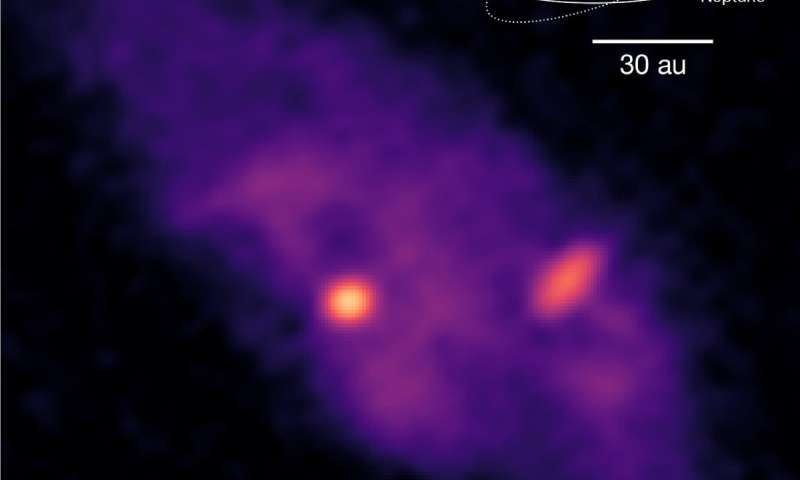

] Detailed view of the binary proto-star system with a size comparison to our solar system. The separation between the sources A1 and A2 is roughly the diameter of the Pluto orbit. The size of the disk around A1 (unresolved) is about the diameter of the asteroid belt. The size of the disk around A2 is about the diameter of the Saturn orbit. Credit: MPE

Detailed view of the binary proto-star system with a size comparison to our solar system. The separation between the sources A1 and A2 is roughly the diameter of the Pluto orbit. The size of the disk around A1 (unresolved) is about the diameter of the asteroid belt. The size of the disk around A2 is about the diameter of the Saturn orbit. Credit: MPE