Erik Ortiz, NBC News•June 15, 2020

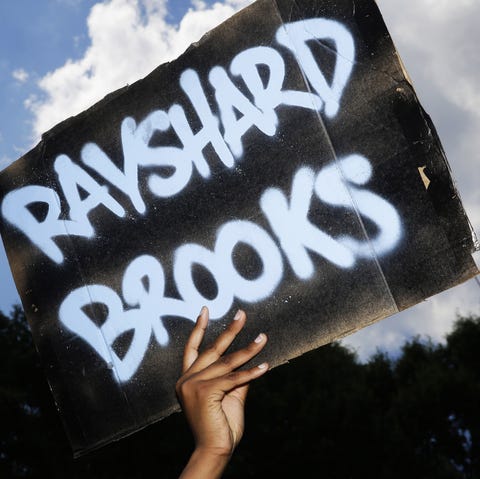

After the deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta and other recent cases of fatal police encounters, the public clamor for changing the culture of policing is running up against powerful opposition in the form of police union leadership.

But in cities like St. Louis, Miami and New York, some of the calls for significant reform are coming from another place: within police departments themselves, among smaller pockets of officers who don't necessarily feel heard by their police unions or the department brass, which are largely white.

While these mostly Black police officers' organizations aren't as big and so don't wield the same influence as unions and fraternal orders with bargaining power and political pull, they do exist in dozens of communities and often share the same views as the residents they serve on issues of racial discrimination, inequality and overaggressive policing.

"This is a new era in America, and we have to embrace the change," said Charles Billups, president of the Grand Council of Guardians, a Black law enforcement association in New York whose membership includes about 3,000 New York Police Department officers. "If you keep recycling those same people in leadership positions, you'll never get real change. We have to get out of the past and move into the future."

But that can prove to be difficult in places like Chicago, where John Catanzara, the newly elected president of the police union, the Fraternal Order of Police Chicago Lodge 7, said last week that any officer in uniform seen kneeling alongside protesters would be subject to discipline, and in Minneapolis, where union boss Lt. Bob Kroll has defied demonstrators' calls to resign over his divisive comments about the Floyd case.

Image: Protesters march near the Minneapolis Police 1st Precinct on June 13, 2020. (Kerem Yucel / AFP - Getty Images)

While Billups said he doesn't support efforts to completely abolish the law enforcement structure, he said the need for addressing racial injustice within policing and the militarization of policing in communities of color are issues that can no longer be ignored.

Until police departments more accurately reflect their communities and, in turn, union leadership represents the diversity of a department, Billups added, legislation that seeks to revamp police procedures will continue to be impeded by an "old guard."

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Friday signed police reform bills that include banning the use of chokeholds and repeal of a law that has kept police disciplinary records secret for decades — legislation that had for years failed to budge under heavy pressure and strong tough-on-crime rhetoric from law enforcement lobbyists.

As mighty as police unions present themselves, they have historically veered away from the larger organized labor movement, which has been outspoken in recent years in support of investigations into fatal police shootings. The Fraternal Order of Police, the largest police union in the United States, for example, is not affiliated with the AFL-CIO.

In a statement Monday, the national FOP's president, Chuck Canterbury, said he is optimistic about police reform efforts under President Donald Trump and the Senate GOP and has provided feedback to the House's bill, which would ban chokeholds and no-knock warrants in drug cases.

"In our view, President Trump and Congressional leaders are working constructively with law enforcement and community stakeholders to undertake earnest law enforcement reforms that will make our officers and the public they protect safer," Canterbury said.

The death of Floyd in the custody of Minneapolis police has been a major catalyst for reform. A Black officers' organization in Miami renewed its complaints about racism within the department and highlighted incendiary remarks by a former police chief in the 1960s — "When the looting starts, the shooting starts" — that were echoed by Trump in recent weeks.

"We're talking about Black men dying. We're talking about systemic racism in police work," Ramon Carr, the vice president of the Miami Community Police Benevolent Association, which has 300 members and represents about 60 sworn officers, said Friday.

The association has clashed with Miami Police Chief Jorge Colina, a 30-year veteran of Florida's largest municipal police department, and on Friday demanded he resign after he confirmed using racist language in 1997 during what he said was a training class.

"We believe Chief Colina harbors implicit biases and it reflects today on the department," Sgt. Stanley Jean-Poix, the association's president, said. "Whenever we talk to him about our issues, he's tone deaf."

But Colina on Friday defended himself in a video, admitting to using "offensive" words, but as a teaching moment. According to internal documents shared by the Miami Community Police Benevolent Association, Colina had used a racial epithet to describe Overtown, a historically Black neighborhood of Miami.

"In 1997, I was an undercover police officer ... and I was teaching a class," Colina said. "I started the class by saying that I was going to be using language that could be very offensive. And that was the point. When you're working undercover, you may have to act and say things you may not normally say otherwise, whether they make you uncomfortable or not. And then I gave many examples of what they could be."

Colina added that the police chief at the time did raise concerns to him about some of the language he used and he was issued a reprimand.

"Not because I'm a bigot or racist, but because they weren't happy with some of the language I used," Colina said.

Related:

He also touted the increased number of Black employees now working for the department during his tenure, and accused a "group of individuals" of using Floyd's death for "self-severing purposes" to push their own agenda.

But members of the Miami Community Police Benevolent Association said they would continue calling on city commissioners to dismiss Colina, saying they believe he has neglected to act sufficiently against officers known to have a pattern of racist complaints against them.

While Billups said he doesn't support efforts to completely abolish the law enforcement structure, he said the need for addressing racial injustice within policing and the militarization of policing in communities of color are issues that can no longer be ignored.

Until police departments more accurately reflect their communities and, in turn, union leadership represents the diversity of a department, Billups added, legislation that seeks to revamp police procedures will continue to be impeded by an "old guard."

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Friday signed police reform bills that include banning the use of chokeholds and repeal of a law that has kept police disciplinary records secret for decades — legislation that had for years failed to budge under heavy pressure and strong tough-on-crime rhetoric from law enforcement lobbyists.

As mighty as police unions present themselves, they have historically veered away from the larger organized labor movement, which has been outspoken in recent years in support of investigations into fatal police shootings. The Fraternal Order of Police, the largest police union in the United States, for example, is not affiliated with the AFL-CIO.

In a statement Monday, the national FOP's president, Chuck Canterbury, said he is optimistic about police reform efforts under President Donald Trump and the Senate GOP and has provided feedback to the House's bill, which would ban chokeholds and no-knock warrants in drug cases.

"In our view, President Trump and Congressional leaders are working constructively with law enforcement and community stakeholders to undertake earnest law enforcement reforms that will make our officers and the public they protect safer," Canterbury said.

The death of Floyd in the custody of Minneapolis police has been a major catalyst for reform. A Black officers' organization in Miami renewed its complaints about racism within the department and highlighted incendiary remarks by a former police chief in the 1960s — "When the looting starts, the shooting starts" — that were echoed by Trump in recent weeks.

"We're talking about Black men dying. We're talking about systemic racism in police work," Ramon Carr, the vice president of the Miami Community Police Benevolent Association, which has 300 members and represents about 60 sworn officers, said Friday.

The association has clashed with Miami Police Chief Jorge Colina, a 30-year veteran of Florida's largest municipal police department, and on Friday demanded he resign after he confirmed using racist language in 1997 during what he said was a training class.

"We believe Chief Colina harbors implicit biases and it reflects today on the department," Sgt. Stanley Jean-Poix, the association's president, said. "Whenever we talk to him about our issues, he's tone deaf."

But Colina on Friday defended himself in a video, admitting to using "offensive" words, but as a teaching moment. According to internal documents shared by the Miami Community Police Benevolent Association, Colina had used a racial epithet to describe Overtown, a historically Black neighborhood of Miami.

"In 1997, I was an undercover police officer ... and I was teaching a class," Colina said. "I started the class by saying that I was going to be using language that could be very offensive. And that was the point. When you're working undercover, you may have to act and say things you may not normally say otherwise, whether they make you uncomfortable or not. And then I gave many examples of what they could be."

Colina added that the police chief at the time did raise concerns to him about some of the language he used and he was issued a reprimand.

"Not because I'm a bigot or racist, but because they weren't happy with some of the language I used," Colina said.

Related:

He also touted the increased number of Black employees now working for the department during his tenure, and accused a "group of individuals" of using Floyd's death for "self-severing purposes" to push their own agenda.

But members of the Miami Community Police Benevolent Association said they would continue calling on city commissioners to dismiss Colina, saying they believe he has neglected to act sufficiently against officers known to have a pattern of racist complaints against them.

https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=FOP

Related:

The demands for reform from within are playing out differently in other cities where the racial dynamics all depend on who holds power.

St. Louis' police union, which represents about 1,300 rank-and-file members of the Metropolitan Police Department, has sparred with Police Chief John Hayden, who is Black, over his handling of protests this month related to Floyd's death.

In a letter to Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican, the St. Louis Police Officers' Association said that officers had lost confidence in Hayden for failing to squelch unrest, and that the state should deploy the highway patrol and the National Guard. Among the violence that roiled the city was the shooting of four police officers and the killing of David Dorn, a retired St. Louis police captain who was shot while responding to looting at a friend's pawn shop.

But in a retort to the union, Hayden took a swipe at union business manager Jeffrey Roorda, saying in a tweet that Roorda "feels a need to thrive on crisis, attempts to invoke panic, and is accustomed to an environment wherein he can control the Chief of Police. A person who is as controversial and divisive as he is, through his words and actions, has no seat at my table, and I am not alone in this sentiment."

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and alerts

Roorda did not immediately return a request for comment about how the union views calls for police reform.

Roorda, who is white, has been an outspoken proponent of officers' rights and incited a controversy last year when he posted on Facebook "Happy Alive Day" to Darren Wilson, the former Ferguson, Missouri, police officer on the fifth anniversary of the day Wilson, who is white, fatally shot Michael Brown, a black teenager.

Roorda has also been at odds with Kim Gardner, the city's first black chief prosecutor, who earlier this year grabbed headlines for suing the city, the police union and others for what she called a "racially motivated conspiracy" to prevent her from doing her job. Roorda has dismissed Gardner's claims, saying that she wants to "persecute cops instead of prosecuting criminals."

Hayden has found some support from the city's mostly Black police organization, the Ethical Society of Police, which is not a traditional union like the Police Officers' Association but does offer legal representation for its roughly 315 members.

Homicide Sgt. Heather Taylor, the society's president and a 20-year St. Louis police veteran, said the Police Officers' Association should be expected to defend officers in the face of disciplinary action or accusations of wrongdoing, but she believes that white officers, who make up about 65 percent of the department, are given preferential treatment over Black officers. The number of Black officers, she added, has fallen in recent years, from 36 percent to 30 percent of the department.

"The POA has never filed a lawsuit about discrimination when we know there's systemic racism," Taylor said. "If representation hasn't been equal for all officers along racial lines, what do you think it's going to be like for the community that encounters these bad officers?"

The Ethical Society of Police is supportive of legislation introduced last week by the St. Louis Board of Aldermen to reform use-of-force policies, although Taylor said city leaders for years have lacked the conviction to act, particularly after the fatal police shooting of Anthony Lamar Smith, a Black man, in 2011 and the violent unrest that followed in 2017 after the white officer who killed him was acquitted of murder.

Marcia McCormick, a law professor at St. Louis University who has researched the police union's role in the city, said St. Louis has a long, complicated history of people holding on to power to the benefit of their social circles — and to the detriment of Black citizens who have historically endured the effects of segregation and higher arrest rates.

Until change comes to these institutions, sweeping police reform will likely remain out of reach, McCormick added.

"That's the challenge," she said, "is that it doesn't happen."