Racism and prejudice

Post-Brexit bigotry was already escalating when the coronavirus pandemic unleashed a new wave of Sinophobia. Rather than retreat, the UK’s Asian community is lobbying the media, public figures and politicians to promote solidarity

Simon Parry Published: 31 May, 2020

Why you can trust SCMP

10.4k

David Tse Ka-shing was taking his daily exercise, jogging through Soho in the heart of London, in the early days of Britain’s coronavirus lockdown in March, when he found himself at the receiving end of a racist outburst that dragged him back to the darkest times of his childhood.

The Hong Kong-born actor and director had just passed a white, female pedestrian in her early 30s at a safe distance when she barked at him to “F*** off back to China.” When Tse turned back in dismay and replied, “I’m British. How dare you?”, she yelled, “Take your f***ing virus home with you.”

For Tse, 55, who moved to England with his family at the age of six, the foul-mouthed outburst was a shocking wake-up call to a tide of racism unleashed by the coronavirus pandemic in his adopted country.

“The UK was incredibly racist when I grew up here in the 70s and 80s,” he recalls of his boyhood in the West Midlands town of Leominster. “We lived in a small market town and my parents ran a fish-and-chip shop and Chinese takeaway. Every Friday and Saturday night we used to get racist behaviour from drunken customers. They would come in to be served and at the same time abuse us.

Tse with his mother, Tse Lai Oi-lin, and father, Tse Siu-kay, outside their Golden Dragon takeaway in Leominster, in the 1980s. Photo: Red Door News

“This happened throughout my childhood because me and my siblings all worked in my parents’ takeaway when we were old enough. My parents were somewhat shielded because they were working in the kitchen, so we bore the brunt of it.

“I remember thinking, ‘Why the hell did we ever leave Hong Kong?’ I grew up on

Cheung Chau, part of a warm, loving, interconnected large community of family and friends. I had an idyllic childhood and then I arrived in this country that was cold, grey and unwelcoming.”

Tse came to believe Britain had grown more civilised and tolerant. He was the founding artistic director of the Yellow Earth Theatre, which showcases East Asian talent, and has directed productions at the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Barbican.

The unprovoked hostility in Soho “brought out the anger in me because you scratch the surface, and suddenly you’re back to a much darker period of British cultural history, when people were overtly racist”, he says. “I think people here are still racist towards Chinese and East Asians, although there was a grudging respect because of the way China has advanced and become an economic superpower. All that seems to have changed with

Covid-19.”

Tse’s experience is far from unique. In the first three months of 2020, police say there have been at least 267 recorded hate crimes against Chinese, East Asian and Southeast Asian people in Britain, compared with 375 in the whole of 2019. Thousands more are believed to have gone unreported.

A survey of more than 400 people of these ethnicities living in Britain found more than a third had experienced racism in public places since the beginning of the outbreak. Researchers warn incidents are likely to increase as the lockdown is lifted.

In a matter of weeks, a country mostly seen as diverse, tolerant and generally welcoming has become a toxic mixture of post-

Brexit racism and Sinophobia, a sometimes menacing place for a resident population of more than 430,000 Chinese people, as well as more than 120,000 Chinese students at British universities.

The threat was most vividly illustrated in early March by a vicious attack on Singaporean student Jonathan Mok, who was left with a black eye, a broken bone below his eye and a swollen face after being attacked by a two teenagers in Oxford Street, just a few minutes’ walk from where Tse would later be verbally abused. Mok told police that as the teenagers attacked him, one shouted, “I don’t want your coronavirus in my country.”

Jonathan Mok posted this picture of his injuries on Facebook after the Singapore student was attacked in Oxford Street, London. Photo: Facebook / Jonathan Mok

Post-Brexit bigotry was already escalating when the coronavirus pandemic unleashed a new wave of Sinophobia. Rather than retreat, the UK’s Asian community is lobbying the media, public figures and politicians to promote solidarity

Simon Parry Published: 31 May, 2020

Why you can trust SCMP

10.4k

David Tse Ka-shing was taking his daily exercise, jogging through Soho in the heart of London, in the early days of Britain’s coronavirus lockdown in March, when he found himself at the receiving end of a racist outburst that dragged him back to the darkest times of his childhood.

The Hong Kong-born actor and director had just passed a white, female pedestrian in her early 30s at a safe distance when she barked at him to “F*** off back to China.” When Tse turned back in dismay and replied, “I’m British. How dare you?”, she yelled, “Take your f***ing virus home with you.”

For Tse, 55, who moved to England with his family at the age of six, the foul-mouthed outburst was a shocking wake-up call to a tide of racism unleashed by the coronavirus pandemic in his adopted country.

“The UK was incredibly racist when I grew up here in the 70s and 80s,” he recalls of his boyhood in the West Midlands town of Leominster. “We lived in a small market town and my parents ran a fish-and-chip shop and Chinese takeaway. Every Friday and Saturday night we used to get racist behaviour from drunken customers. They would come in to be served and at the same time abuse us.

Tse with his mother, Tse Lai Oi-lin, and father, Tse Siu-kay, outside their Golden Dragon takeaway in Leominster, in the 1980s. Photo: Red Door News

“This happened throughout my childhood because me and my siblings all worked in my parents’ takeaway when we were old enough. My parents were somewhat shielded because they were working in the kitchen, so we bore the brunt of it.

“I remember thinking, ‘Why the hell did we ever leave Hong Kong?’ I grew up on

Cheung Chau, part of a warm, loving, interconnected large community of family and friends. I had an idyllic childhood and then I arrived in this country that was cold, grey and unwelcoming.”

Tse came to believe Britain had grown more civilised and tolerant. He was the founding artistic director of the Yellow Earth Theatre, which showcases East Asian talent, and has directed productions at the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Barbican.

The unprovoked hostility in Soho “brought out the anger in me because you scratch the surface, and suddenly you’re back to a much darker period of British cultural history, when people were overtly racist”, he says. “I think people here are still racist towards Chinese and East Asians, although there was a grudging respect because of the way China has advanced and become an economic superpower. All that seems to have changed with

Covid-19.”

Tse’s experience is far from unique. In the first three months of 2020, police say there have been at least 267 recorded hate crimes against Chinese, East Asian and Southeast Asian people in Britain, compared with 375 in the whole of 2019. Thousands more are believed to have gone unreported.

A survey of more than 400 people of these ethnicities living in Britain found more than a third had experienced racism in public places since the beginning of the outbreak. Researchers warn incidents are likely to increase as the lockdown is lifted.

In a matter of weeks, a country mostly seen as diverse, tolerant and generally welcoming has become a toxic mixture of post-

Brexit racism and Sinophobia, a sometimes menacing place for a resident population of more than 430,000 Chinese people, as well as more than 120,000 Chinese students at British universities.

The threat was most vividly illustrated in early March by a vicious attack on Singaporean student Jonathan Mok, who was left with a black eye, a broken bone below his eye and a swollen face after being attacked by a two teenagers in Oxford Street, just a few minutes’ walk from where Tse would later be verbally abused. Mok told police that as the teenagers attacked him, one shouted, “I don’t want your coronavirus in my country.”

Jonathan Mok posted this picture of his injuries on Facebook after the Singapore student was attacked in Oxford Street, London. Photo: Facebook / Jonathan Mok

Now a group of prominent Chinese, East Asians and Hongkongers living in Britain have banded together to fight the rising tide of attacks and discrimination. CARG –

the Covid-19 Anti-Racism Group – has launched a petition calling on

Prime Minister Boris Johnson to make a clear declaration that the British government “deplores racism and hate crimes arising from Covid-19 against British East Asian people and international students in our country”.

The group also issued a statement calling on the media, public figures and political leaders to emphasise “solidarity, courage and mutual support across all communities rather than feed hostility, division and racism”.

The depth of concern among Chinese and East Asian communities in Britain can be seen in the messages posted by people signing up to CARG. “I’m living in fear for my children and me because of the rising hate crimes,” wrote one. “I’m very worried about my future as a British Chinese living in the UK,” wrote another.

“We’ve had Brexit already so there’s a lot of racist anti-immigrant thinking in this country and now it’s being stoked further,” says Tse, a founding member of CARG. “It is a very dangerous time we are living in. Some Hong Kong students might want to think twice about coming here. I wouldn’t want Hongkongers and mainland Chinese to put their lives at risk. It’s only a matter of time before this Brexit ‘Britain First’ toxicity affects one of us very badly.

They have racialised a disease and they are promoting Sinophobic propaganda, echoing what the Nazis did in Germany against the Jews

David Tse

“They are playing the racecard and scapegoating. They have racialised a disease and they are promoting Sinophobic propaganda, echoing what the Nazis did in Germany against the Jews. People are angry. It’s like the 1930s in the sense that the economy is going to tank and people are listening more to extremist voices. Propaganda works, especially when people are hurting.”

“They are playing the racecard and scapegoating. They have racialised a disease and they are promoting Sinophobic propaganda, echoing what the Nazis did in Germany against the Jews. People are angry. It’s like the 1930s in the sense that the economy is going to tank and people are listening more to extremist voices. Propaganda works, especially when people are hurting.”

At the root of the problem, Tse believes, is the fact that while Asian countries have handled the coronavirus effectively, Britain’s approach has been marred by “complacency, negligence and incompetence”. He says, “It shows the residual colonialism, arrogance and the notion they knew better because they were more advanced and more civilised.

“They were looking down their noses and treating it as a foreign disease that could not possibly affect plucky little Britain. We had nine weeks to prepare and throughout that time I was aware of the severity of the outbreak because all my family and friends in Hong Kong were WhatsApping me on a daily basis. But the government here was just twiddling its thumbs.”

In April, arts patron and CARG founding member Geoff Leong had all four tyres on his Mercedes slashed outside the house he shares with his wife, Marie-Claire, and their three children in north London.

Geoff Leong with wife Marie-Claire. Photo: Red Door News

The founder of Dumplings’ Legend restaurant, in London’s Chinatown, a favourite among celebrities and royalty, believes his car was targeted by someone who knew he was Chinese. He responded by writing the word “Why?” on each damaged tyre and posting a message on the car asking: “How is my NHS (National Health Service) doctor wife going to get to work today?”

“We have to stop this,” Leong says. “There must be no more of this prejudice. People have to speak with a strong voice against race crime, not just put their heads down and ignore it.”

He noticed attitudes to Asians in London had begun to change when he saw a woman stepping to one side and “staring me out” in a shop before the lockdown began. “It was like a comic scene at first,” he says. “Another time, a couple were walking their dog and saw me approach and literally dragged their dog aside to get it away from me – and this was before social distancing was introduced.”

Soon after, Leong’s 12-year-old daughter was shouted at by a woman in their local supermarket and Leong “went back to the shopkeeper who had seen it happen and I said it was really wrong and that you need to stand up to people who do these things”.

Leong with Stephen Fry (second from right) in London, in 2017. Photo: Red Door News

Having moved to Britain from Hong Kong at the age of 10, to attend boarding school, Leong says the atmosphere in London is markedly different now. “London is a very diverse, metropolitan city, people know about political correctness, but the agenda changed when Brexit came and when Trump came. Now, people are thinking, ‘You look Chinese, you look East Asian, you must have Covid-19.’ That is absolutely wrong and we have to stamp this out.”

An early focus of CARG’s campaign were reports in the British press that they say racialised Covid-19 and created “a climate of fear, anger and hatred” towards British Chinese and East and Southeast Asian communities. References to the pandemic as “the Chinese virus” and attempts by the government to deflect criticism of its failure to prepare for the coronavirus’ arrival have triggered racist attacks and attitudes, the group claims.

British-born Chinese Pek-san Tan, who works as head of press at the London Chinatown Chinese Association and whose parents-in-law are from Hong Kong, is concerned about the potential long-term impact of “casual racism” on her children, aged five and three.

Before schools closed and the lockdown began, young children were playing games of coronavirus “it” in some primary school playgrounds and singling out Asian pupils, she says. “I had seen what was happening and I didn’t think young impressionable minds should be subjected to that because you don’t know what psychological effect it will have on them in the future.”

A shop owner outside her business in Holloway Road. Photo: Alex Hofford

Since the outbreak began, Tan has not taken her children on public transport. Fortunately, her children were at home when she was confronted by three girls who verbally abused her as she walked through a London Underground station with an elderly relative in February. “They started swearing about the coronavirus and using the worst expletives you can imagine,” she says. “I told them they were being ignorant and that the virus doesn’t discriminate.”

Minutes later, as she spoke on her phone to the British Transport Police to report the incident outside the station, Tan was subjected to a second assault. “A well-dressed couple came towards me and the man walked right up to me and coughed in my face,” she says.

Tan says it is important to confront Sinophobia early to stop it spreading. “I know the Chinese community are having it really bad now but I look to other communities in the country – my Muslim friends or my black friends, who have a whole history of racism against them – and I think this is the poem And then they came for me.

“What we are doing with CARG is firefighting an immediate issue in our own city, because we are British citizens and this is our home, and I can’t bear to see my countrymen descend into this sort of discrimination.”

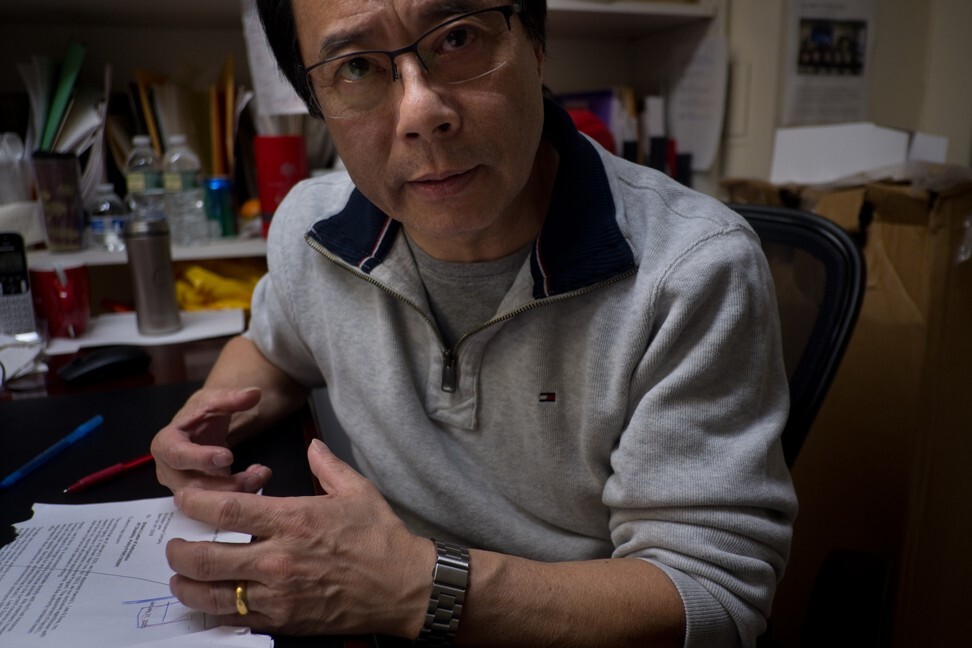

David Tse. Photo: Red Door News

This rising tide of race attacks and Britain’s inability to contain it could have an impact on the number of Chinese and East Asian students who sign up for universities in the country. More than 120,000 attended in the last academic year – a 30,000 increase on 2014-15 – but it is unclear how many will return in the autumn.

For now, at least, it appears racism is not their biggest worry, according to Tan, who has spoken to friends with children at British universities. “The way they see it is that racism is everywhere and their biggest concern is whether the UK health care system can sort itself out and people can learn to wear masks,” she says.

Whether the Covid-19 racism coursing through Britain outlives the pandemic or dies away with it remains to be seen. Whatever happens, walking away is not an option for Tse and many others for whom Britain has been home for decades.

“If I were to leave now and go back to Hong Kong, it would feel like running away from a problem that needs to be resolved,” he says.

Instead, when he found himself confronted by bigotry in Soho, he made sure that – unlike during his days behind the counter in his parents’ takeaway – he wasn’t going to let a racist have the last word. “When she had finished yelling at me, I said, ‘F*** your f***ing racism and your f***ing paranoia,’” he says. “She seemed quite shocked that a Chinese person was assertive enough to answer her in the same way she had spoken to me.”

A chronology of racism – ‘We are not welcomed’

January 30 A female Chinese student in Sheffield, where there are 8,000 Chinese students, is shoved and abused in the street for wearing a face mask. Sarah Ng, from the Sheffield Chinese Community Centre, says the student was following advice from the media in mainland China and Hong Kong to wear a mask but said the sight of them added to a sense of “panic” in the population.

“We need to put out a balanced message of understanding about why Chinese students are wearing masks,” she suggests.

February 3 Two Asian students aged 16 and 17 are pelted with eggs in Market Harborough, Leicestershire. University of Leicester students also report being subjected to racist attacks for wearing masks.

February 8 Financial worker Pawat Silawattakun, 24, from Thailand, is assaulted and robbed as he gets off a bus in Fulham Road, London, by two teenagers who punch him, breaking his nose, and run away with jeers of “coronavirus”. “It’s made me very wary. It isn’t just a robbery. There’s also knowing I’ve been targeted because of my ethnicity,” he says.

A woman wears a mask during Lunar New Year celebrations in London’s Chinatown, on January 26. Photo: AFP

A woman wears a mask during Lunar New Year celebrations in London’s Chinatown, on January 26. Photo: AFPFebruary 9 A 28-year-old Chinese woman in Birmingham is accused of having coronavirus, called “a dirty c***” and told to “take your f***ing coronavirus back to China”. An Indian friend of the woman, who steps in to protect her, is punched unconscious and hospitalised.

In another incident in the city, a Chinese student is reportedly punched in the face for wearing a face mask and suffers a dislocated jaw. A spokeswoman for the Birmingham Chinese Society says: “There has always been abuse. The virus has given some individuals a reason for that abuse.”

February 24

Singaporean student Jonathan Mok, 23, is left bleeding and bruised after being beaten up in Oxford Street, London, by a gang of four teenagers who shout: “We don’t want your coronavirus in our country.” Two boys aged 15 and 16 are later arrested for racially aggravated assault. Mok says: “I just think it’s a pity to have such experiences taint the image of this beautiful city with so many nice people.”

March 5 A PhD student from China studying at Scotland’s Glasgow University has his clothes torn by a gang of three attackers, who shout “coronavirus” at him. Politician Sandra White says: “To attack an innocent person in the street for no other reason than sheer ignorance is utterly appalling.”

Police CCTV pictures show the two suspects in Jonathan Mok’s attack. Photo: MET / Red Door News

March 12 A teenager spits in the face of a Chinese takeaway owner in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, shouting: “Do you have coronavirus? Do you have coronavirus?” The owner’s daughter, Sharon So, says: “We are worried for my father’s health. What if that boy had the virus? He spat in my dad’s face – my dad could easily be infected.”

March 20 Four Chinese people in their 20s wearing face masks are attacked in Southampton, in southern England, by youths aged 11 to 13 in what police described as a racially aggravated attack linked to the coronavirus outbreak.

March/April Students around Britain report being attacked and abused for wearing face masks. A 24-year-old Chinese postgraduate student in Manchester describes being targeted by a passing car while shopping with a friend: “They rolled down the window and sneezed at us and then laughed.” Some students have stopped going out because of the threat of abuse. “I feel like an outsider,” one says. “We are not welcomed.”