An excerpt from Art, Global Maoism and the Chinese Cultural Revolution, edited by Jacopo Galimberti, Noemi de Haro García and Victoria H. F. Scott, explores the contradictions inherent in the global spread of China’s 20th century political doctrine

Manchester University Press Published: 1 Mar, 2020

Art and images were and continue to be central channels for the transnational circulation and reception of Maoism. Though it is rarely acknowledged as such, the so-called Great Chinese Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-76) was one the most extraordinary political upheavals of the 20th century. And similarly, no other post-war statesman has elicited more conflicted emotions than Mao.

“Contradiction is present in the process of development of all things; it permeates the process of development of each thing from beginning to end.”Mao Zedong, ‘On Contradiction’, 1937

Indeed, despite being responsible, by some controversial accounts, for tens of millions of deaths, the man known as the Great Helmsman is still widely revered both inside and outside China, and in the 21st century, the contested legacy of this powerful figure has only expanded.

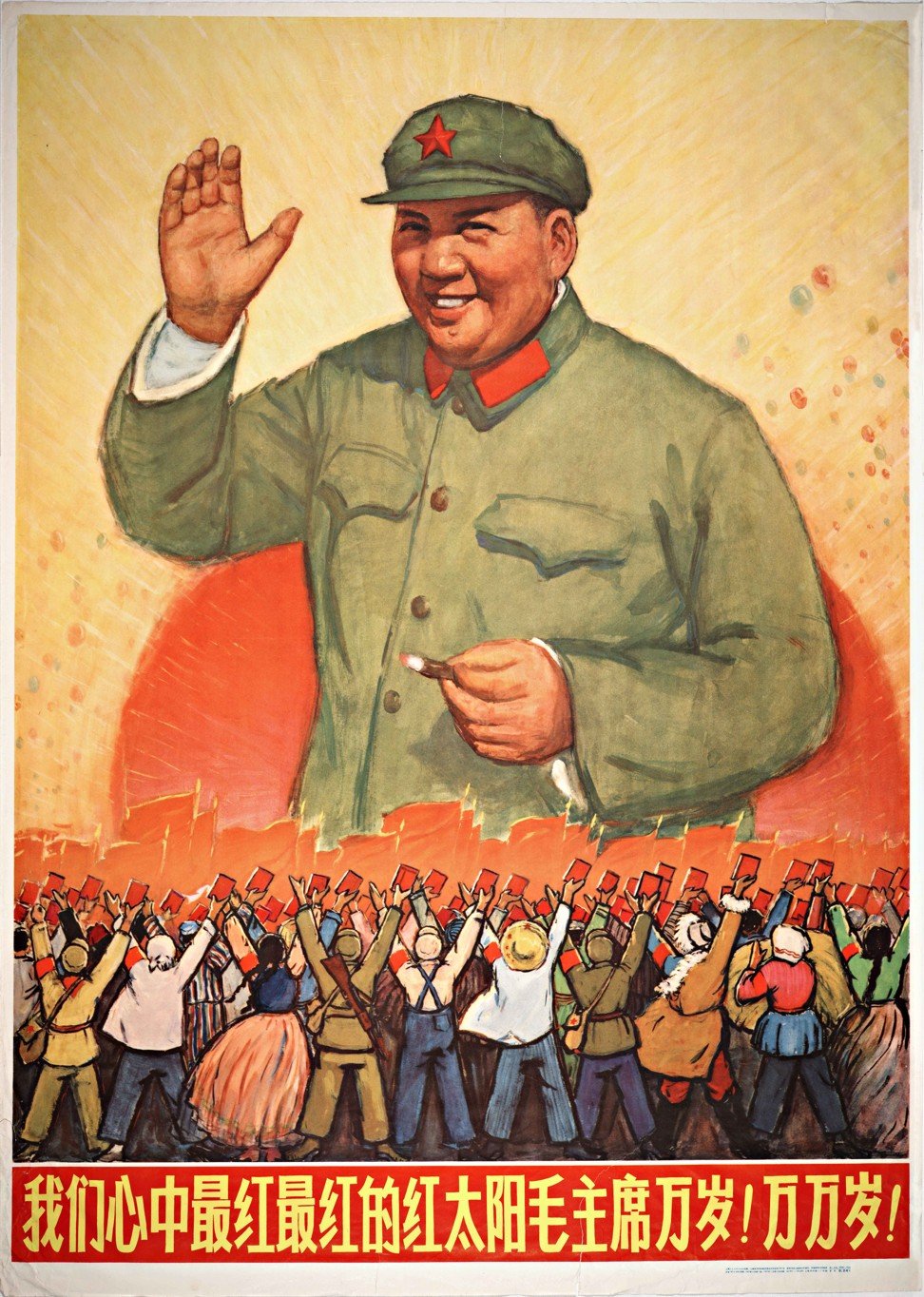

A 1967 poster features an illustration of Mao Zedong above the phrase “Raise High the Great Red Flag of Mao Zedong Thought to Carry Out to the End the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”. Photo: Getty Images

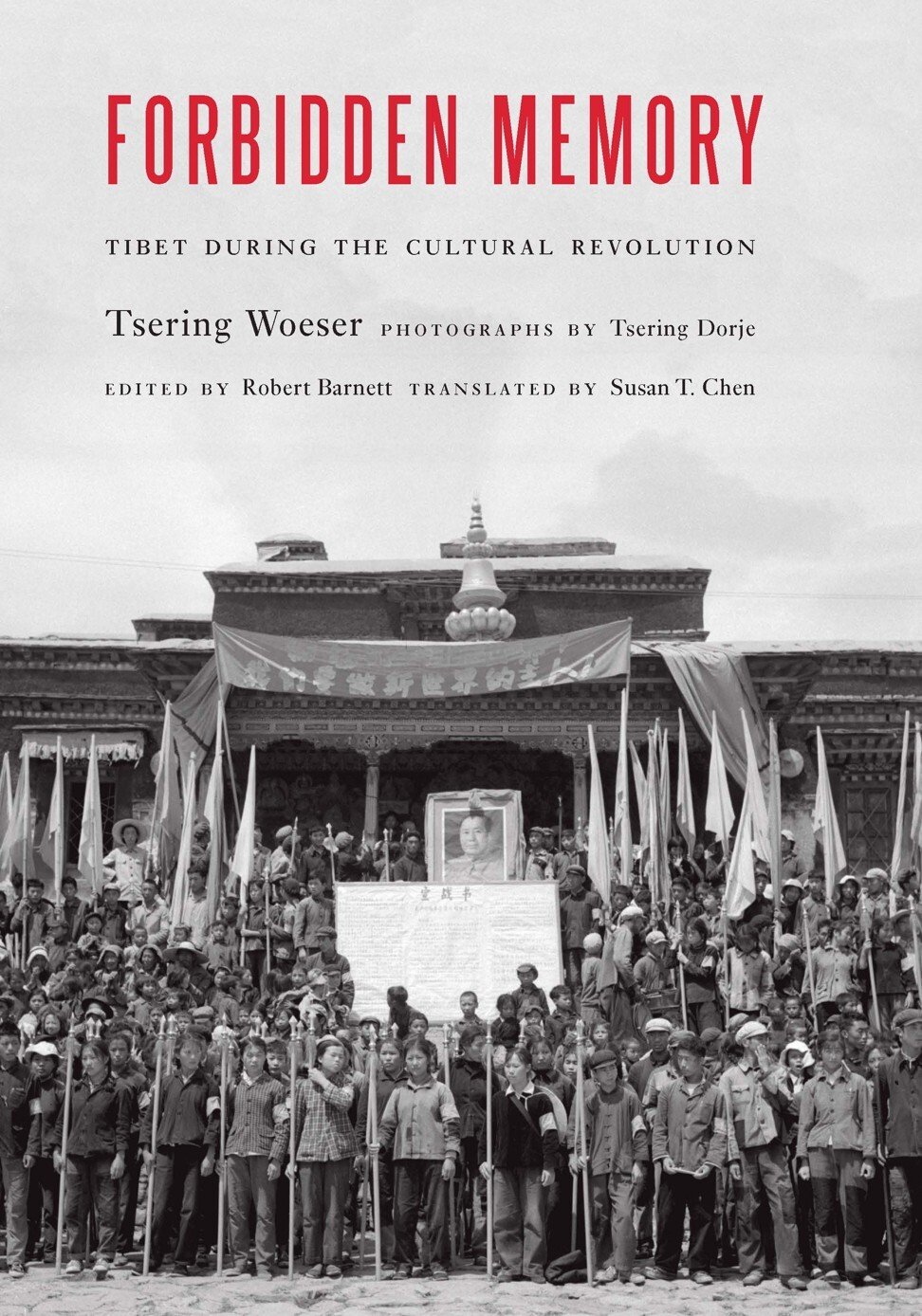

Marking the 50-year anniversary of the Cultural Revolution, in both China and other countries, academic research produced pioneering studies of the Red Guards, the Shanghai People’s Commune, the “little red book” and seminal theoretical disputes (opposing, for instance, Mao to Deng Xiaoping). Some aspects of Maoism are being reassessed, partly because they speak to the present moment, such as Maoism’s critique of colonialism and racism.

If the 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of anti-colonial struggles, and “an awakening sense of global possibility, of a different future”, this should also be ascribed to Maoism. Thus it comes as no surprise that Fredric Jameson viewed Maoism, rightly or wrongly, as “the richest of all the great new ideologies of the 1960s”, when the idea of “Maoist China” became a productive epistemological device to reimagine the world, to reinterpret its hierarchies and to act to change them.

Maoism preceded the Cultural Revolution, and can be traced to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, or even earlier. It was, however, only with the Sino-Soviet split and China’s experiments with nuclear weapons that it gained real momentum. Mao’s sustained criticism of the peaceful coexistence between the two superpowers, as well as his advocacy of armed struggles in the Third World, broke what many regarded as the theoretical and geopolitical impasse of Marxism.

Art and images were paramount in the dissemination and reception of Maoism’s revolutionary ambitions. Not only could they travel fast to distant places, but some visual conceits could also be easily adapted to specific contexts.

In recent years there has been a scholarly reappraisal of the art produced in China between 1966 and 1976. No longer stigmatised, this type of visual propaganda has been widely examined, helping to shed new light on the semantics, aesthetics and memories associated with Maoist plays, posters, photographs, paintings and artefacts of all sorts.

Gold drew the Chinese to Australia, why is their legacy largely forgotten?

The dynamics created by travelling objects (model works, “little red books”, posters, badges, pamphlets, journals, etc), people (intellectuals, party cadres, diplomats, activists, etc) and ideas associated with Maoism had an enormous impact. However, any effort to delineate the “standard Maoist position” on the arts is probably doomed to failure because of the long history, complex networks and diverse practices into which Maoism has crystallised. By the same token, searching for the putative “essence” of a Maoist aesthetic in Mao’s founding texts leads to an impasse.

The lecturer on modern Chinese history and literature

Julia Lovell has observed that the Cultural Revolution did not attract significant interest among students in the United States until 1968, when it began to resonate strongly with their own anti-establishment sentiment. She concludes that this identification is “far more informative about the preoccupations of these distant observers of Chinese politics than about Chinese politics itself”.

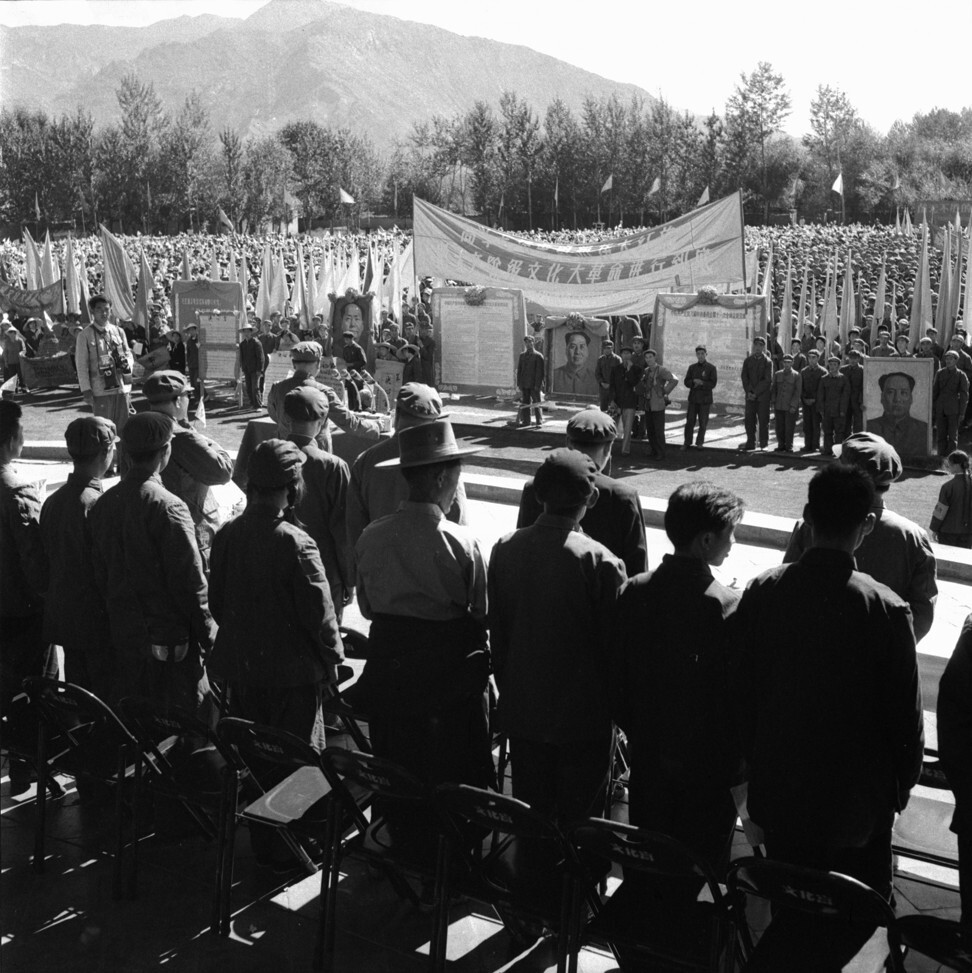

Students at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing create political artworks. Photo: Getty Images

In his study of the anti-authoritarian Left in West Germany, the historian Timothy Scott Brown echoes Lovell’s remarks. He maintains that the reception of images associated with Maoism “served as a bridge between the global and the local”, and was driven “less by the meaning imputed to images or cultural products at their point of origin, than at the point of their reception”.

Yet scholarly literature has had little to say regarding the role played by art in global Maoism. The wealth of studies and exhibitions about the art of the Cultural Revolution has not been accompanied by comparable analyses of European, African, Asian and American artists who were heavily influenced and inspired by the events in China.

Nor has the recent interest in exploring the worldwide influence of Chinese communism in the 1960s and 1970s been met by a commitment to analysing the visual components of its reception. The omission is surprising, as for several years this global phenomenon shaped the work and thought of major artists as diverse as John Cage and Jörg Immendorff, to name just two.

For more than a decade, global Maoism permeated art production in a variety of ways that continue to be neglected by standard art-historical accounts of the post-war period. Caught between a cult of personality and libertarian impulses, thousands of artists, architects, designers and film directors appropriated or emulated the political ideals of the Cultural Revolution, translating them into a wide variety of visual propositions.

A Soviet communist poster. Photo: Getty Images

From the Californian campuses to the Peruvian campesinos, many attempted to integrate Mao’s principles and the Cultural Revolution’s material culture, iconography and slogans into their production and model of authorship, although in different, and at times highly incompatible, ways.

It is unlikely that the lack of scholarship on this topic is accidental. The widespread apprehension concerning the attribution of historical significance and intellectual sophistication to the Maoist phase of several American and European artists is directly related to the political implications of espousing Mao Zedong Thought in the West. On the one hand, the predominant narratives of art history are still embedded in the Cold War dualistic conceptual frameworks, setting capitalism against communism.

Modern art and modernism were long ago constructed as the counterpoint to the propaganda of so-called totalitarian art, which brought durable discredit upon the latter. On the other hand, the current presence of Maoist guerillas makes the topic politically sensitive in several countries, pushing scholars to see Maoist artistic production as secondary over issues of state security. Moreover, claiming the political primacy of the Chinese Cultural Revolution challenges the Eurocentrism of both the Left and the Right, which still, occasionally, thinks in terms of “oriental despotism”.

A further reason accounts for the scholarly reluctance to explore Maoist artists. The Red Guards’ “cultural” revolution represented a shocking rejoinder to the Western definition of “culture” as it had emerged since the Enlightenment. Denouncing ancestral traditions and wisdom not as a shared heritage that had to be preserved, but rather as an obstacle to the exigencies of communism, in the West the Red Guards were decried as vandals, destroying culture rather than renewing it

It is unlikely that the lack of scholarship on this topic is accidental. The widespread apprehension concerning the attribution of historical significance and intellectual sophistication to the Maoist phase of several American and European artists is directly related to the political implications of espousing Mao Zedong Thought in the West. On the one hand, the predominant narratives of art history are still embedded in the Cold War dualistic conceptual frameworks, setting capitalism against communism.

Modern art and modernism were long ago constructed as the counterpoint to the propaganda of so-called totalitarian art, which brought durable discredit upon the latter. On the other hand, the current presence of Maoist guerillas makes the topic politically sensitive in several countries, pushing scholars to see Maoist artistic production as secondary over issues of state security. Moreover, claiming the political primacy of the Chinese Cultural Revolution challenges the Eurocentrism of both the Left and the Right, which still, occasionally, thinks in terms of “oriental despotism”.

A further reason accounts for the scholarly reluctance to explore Maoist artists. The Red Guards’ “cultural” revolution represented a shocking rejoinder to the Western definition of “culture” as it had emerged since the Enlightenment. Denouncing ancestral traditions and wisdom not as a shared heritage that had to be preserved, but rather as an obstacle to the exigencies of communism, in the West the Red Guards were decried as vandals, destroying culture rather than renewing it

A poster created by communist trade unions celebrates May Day in Kolkata, India, on May 1, 2006. Photo: AFP

Maoism in India is still very much alive, and in several areas Maoist guerilla fighters continue to combat the Indian state. Sanjukta Sunderason’s chapter “Framing margins: Mao and visuality in 20th century India” maps the traces of Mao and Maoism in India’s long 20th century.

Drawing from the visual culture theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff ’s notion of visuality, Sunderason explores three key moments of Indian Maoism in relation to art: the iconography of resistance developed by the Communist Party of India in the 1940s, the Naxalites’ “statue-smashing” in Calcutta in the early 1970s and the afterlives of Maoism in Indian art from the mid-1970s to the present.

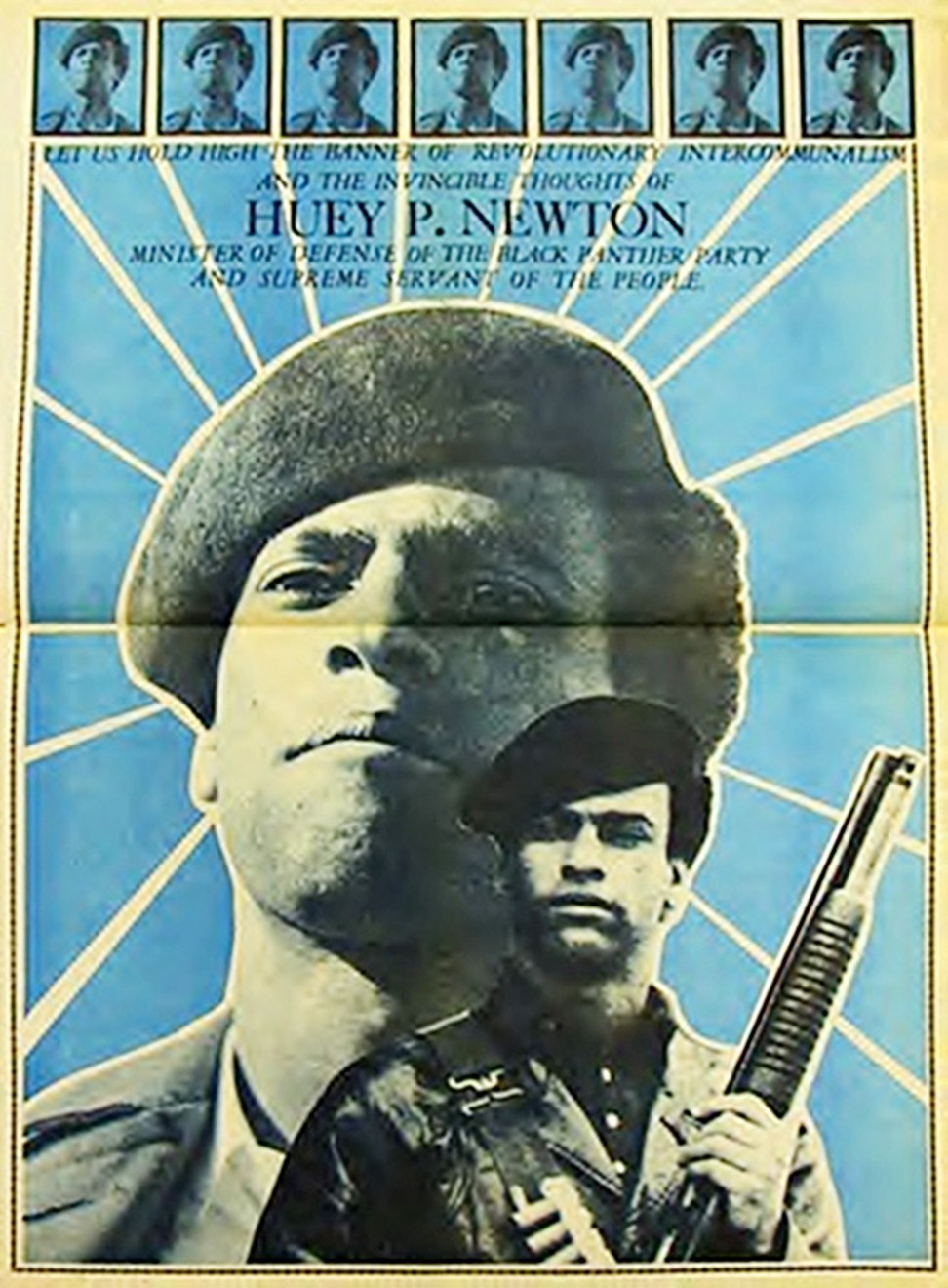

The early 1970s were a key period for Maoism in the US as well. Colette Gaiter’s chapter, “The Black Panther newspaper and revolutionary aesthetics”, looks at the work of the American artist Emory Douglas, the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, which at the time was subscribing to a political tendency known as “intercommunalism”.

More expansive than other strands of leftist thought, intercommunalism sought to unite countries of the world in resistance to global capitalism and imperialism. A wave of “Black Maoism” swept through black liberation movements at this time and came to visual life in Douglas’ work on The Black Panther newspaper.

An image in The Black Panther newspaper. Photo: Getty Images

The analysis then moves to the years of the Cultural Revolution, and to the two industrialised countries that were the first to see the emergence of a large Maoist movement: West Germany and France. Lauren Graber and Daniel Spaulding’s joint contribution, “The Red Flag: the art and politics of West German Maoism”, maps artistic Maoism in West Germany from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, tying it to both the student movement and the extra-parliamentary opposition. Looking at a broad sample of artists, the authors demonstrate how the image of Mao and the politics for which it stood became contested terrain where the complex dialectic of Pop and revolution was played out in perhaps its most spectacular form.

France is the European country where Maoism has had, perhaps, the most lasting and pervasive impact on society, with intellectuals – the most prominent being the philosopher Alain Badiou – continuing to eulogise Mao and the Cultural Revolution. This is especially significant because of the role many French intellectuals from this period had in the formulation and dissemination of postmodernism.

Like their northern neighbours, southern European artists also appropriated the Cultural Revolution’s political ideals and forms of authorship. “La Familia Lavapiés” as a collective, collaborated but also argued with political leaders, mass organisations, political parties (especially the Communist Party), workers, students, neighbours and, of course, other artists.

Sympathetic to acracia (the suppression of any kind of authority, of domination, of power, of coercion) and Trotskyism, the members of La Familia Lavapiés saw art and Maoism as tools with which they unsuccessfully tried to challenge and transform the cultural and political milieu in which they carried out their activities.

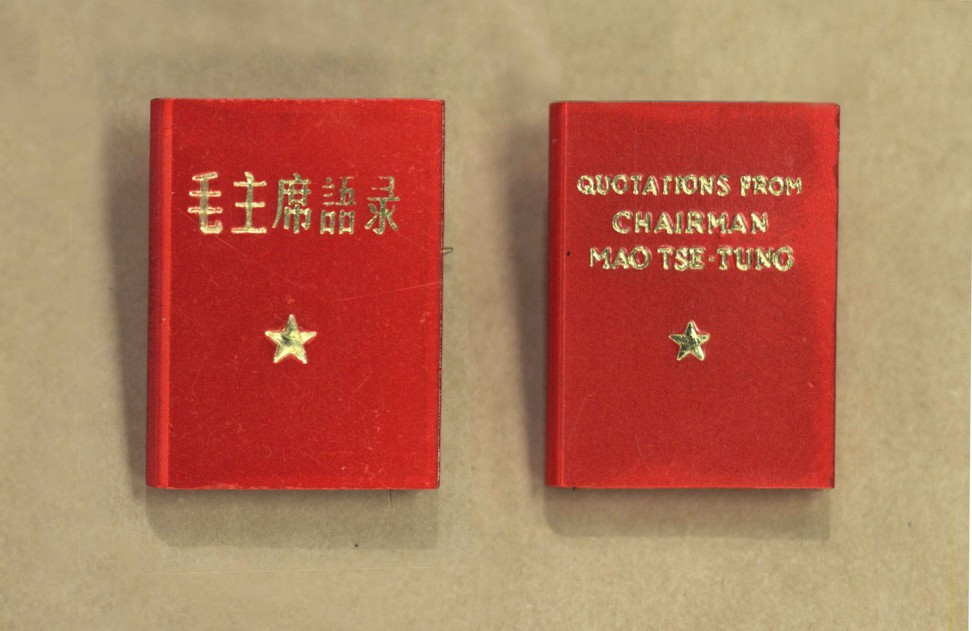

Mao’s “little red book”. Photo: Getty Images

In several countries Maoism was so strongly refracted through the prism of the local specificities that it occasionally became a pretext and even a joke. Could one at once be a Maoist and poke fun at Mao’s cult? By 1976, some Italian militants were advocating a new form of Maoism that conflated pop culture, autonomist Marxism, Gilles Deleuze’s and Félix Guattari’s philosophy and, last but not least, avant-garde art. They defined this trend as “Mao-Dadaism”.

In “Another red in the Portuguese diaspora: Lourdes Castro and Manuel Zimbro’s Un autre livre rouge”, Ana Bigotte Vieira and André Silveira examine Un autre livre rouge, an artists’ book made by the Portuguese artists Lourdes Castro and Manuel Zimbro while they were living in Paris. The two-volume work alluded to Mao’s “little red book” and was entirely devoted to the contradictory meanings and psychological associations that red conveyed.

The work was crafted mostly between 1973 and 1975 at a time of radical political change in Portugal. The Carnation Revolution and the PREC (Período Revolucionário Em Curso, Ongoing Revolutionary Period) informed Un autre livre rouge, which was, however, both less and more than a political book.

The significance of Maoism for global independence movements around the world is an important subject that merits further attention, particularly for countries in Africa, for example. In “Avenida Mao Tse Tung (or how artists navigated the Mozambican Revolution)”, Polly Savage examines Maoism in Mozambique. Drawing on interviews and archival records, the study focuses on the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (or FRELIMO).

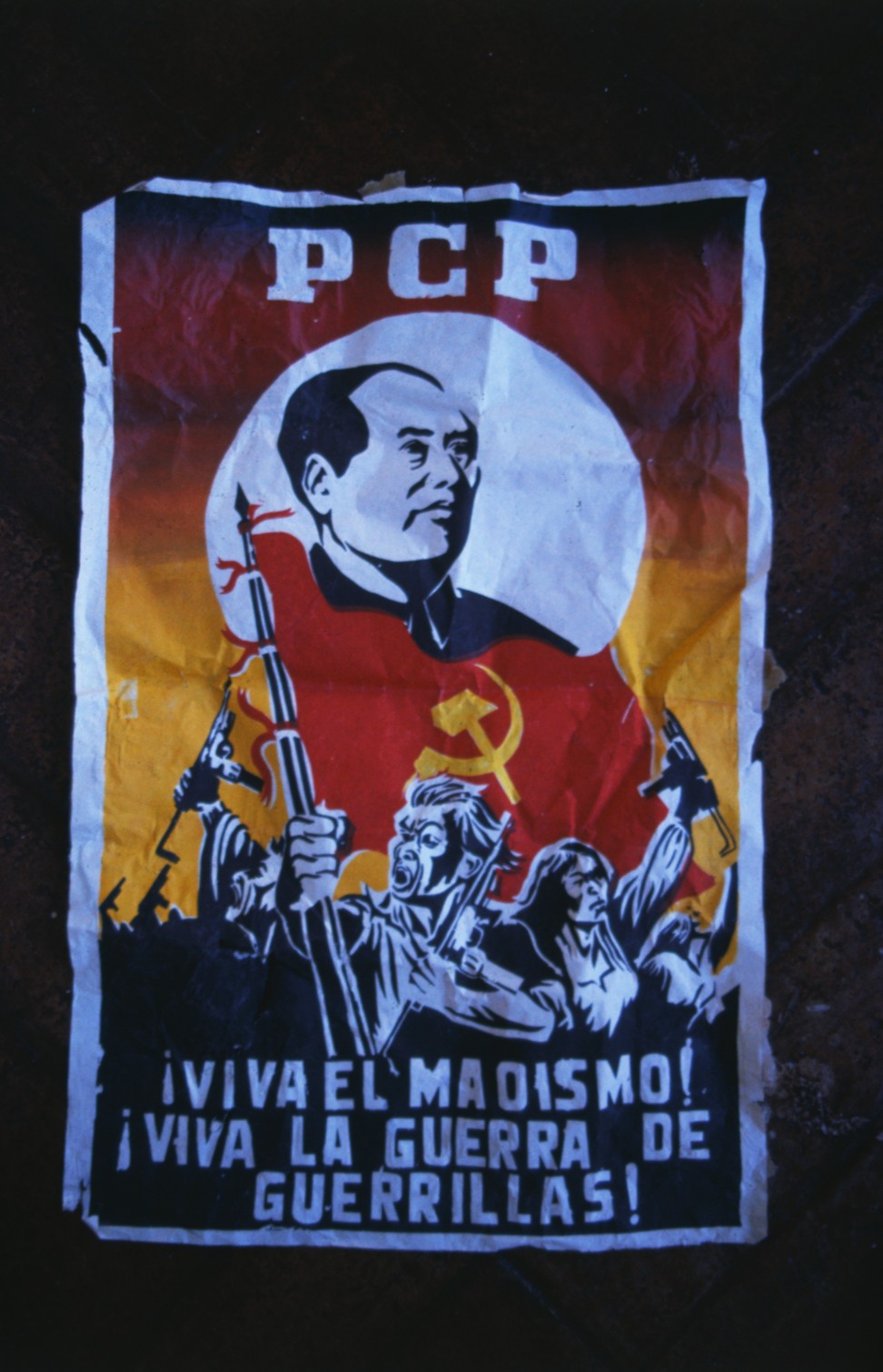

A Peruvian Communist Party poster. Photo: Getty Images

Between 1970 and 1977 FRELIMO negotiated an artistic and cultural agenda combining, not without difficulties, leftist internationalism and local traditions. The analysis of works produced by the graphic designer “Mphumo” João Craveirinha Jnr offers insightful perspectives on how these tensions materialised in images. In the case of the artist Juan Carlos Castagnino, often considered to be the official painter of the Argentinian Communist Party, his relationship with China informed both his politics and his practice.

Peru was on the verge of becoming a Maoist state in 1990, set against the background of the civil war between the Communist Party of Peru (PCP), also known as Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), and the Peruvian state, a conflict that began in 1980 and lasted well into the 1990s.

Austrian art historian Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art, published in 1950, is the world’s bestselling book in the field of art history. In 1953, at the height of McCarthyism, Gombrich wrote a scathing review of Arnold Hauser’s book The Social History of Art. Criticising Hauser’s methodology, Gombrich argued that contradiction was an ontological trap that led to theoretical paralysis. But the notion of contradiction is an insightful one for describing and understanding the impact of Maoism on the visual arts.

Instead of eschewing the paradoxes that animate art history, one must expose them and reveal cultural contradictions for what they have always been: a powerful source of political, social and aesthetic transformation, for better or for worse.

Excerpt from Art, Global Maoism and the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Edited by Jacopo Galimberti, Noemi de Haro García and Victoria H. F. Scott. Published by Manchester University Press