Remembering Marco Leung, the first to die in Hong Kong's anti-China extradition protests

After his death, Leung’s yellow raincoat became a protest symbol

Posted 16 June 2020 12:05 GMT

Marco Leung. Image from the Stand News, Global Voices’ content partner.

Supporters of the anti-China extradition movement in Hong Kong count around a dozen unnatural deaths related to last year's protests.

The majority of the deceased committed suicide — at least six individuals left suicide notes expressing their support of the protests and frustration towards the government.

The most shocking incidents were the deaths of Marco Leung Ling-kit on June 15 and Chow Tsz-lok on November 3.

Marco Leung, 35, was the first to die during the protests.

He fell from Pacific Place, a shopping mall, while he was hanging up a protest banner at 4 PM on June 15, a week after a one million-strong demonstration failed to convince the city's leadership to withdraw the bill.

Marco Leung Ling-kit ( 梁凌杰 )

2019-06-15 Passing away 1 Year 😭

Black shirt + White ribbon 🙏🏻#StandWithHongKong 🙇🏻♀️🙇🏻♀️ pic.twitter.com/kYATHxtIX7

— Apple (@Apple68335100) June 14, 2020

Leung was wearing a yellow raincoat displaying the words “(Chief Executive) Carrie Lam killed Hong Kong, Cops were cold blooded.” (林鄭殺港 黑警冷血).

On the banner he wrote:

Translation

Original Quote

Complete withdrawal of the China-extradition bill. We are not rioters. Release the students and the injured. Step down Carrie Lam. Help Hong Kong. No Extradition to China. Make Love, No shoot!

The Hong Kong government continued to refuse to withdraw the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019, better known as the China extradition bill.

In response, on June 12, thousands of protesters charged towards the Legislative Council (LegCo).

Riot police cracked down on the protest with tear gas and rubber bullet rounds. Authorities labeled the protests as riots, a definition that left the protesters facing sentences of up to ten years in jail.

Marco Leung's individual protest was a reaction to the government's refusal to listen to people's demands and its labelling of citizens as rioters.

He fell to his death after a rescue team launched an attempt to pull him inside the shopping mall. Leung's death shocked all of Hong Kong.

The following day, two million people took to the streets, calling for Carrie Lam to step down as leader along with five other demands reflected in Leung's last stand: Complete withdrawal of the China extradition bill! Stop labeling protests as riots! Drop charges against protesters! Conduct independent investigations into excessive use of police force! Implement universal suffrage for both Legislative Council and the Chief Executive!

Since his death, Leung’s yellow raincoat has become a protest symbol, while protesters have vowed that they will carry on his path and force the fulfilment of his demands.

梁凌杰 1984/3/7 – 2019/6/15

享年35歲。🕯 pic.twitter.com/CAVJm96Syu

— Huckebein (@JOSHUAHUCKEBEIN) June 15, 2020

Leung Ling-kit. 1984/3/7 – 2019/6/15. Aged 35 years old.

It had been a year since you left us. I remeber that you were the first person who say Five Demand. Hong Kongers never forget. 梁凌杰義士,他是被政權推下去。 未能忘記,亦不會忘記. pic.twitter.com/9E71RUM4th

— Linghk ❤ (@lingliberaty) June 15, 2020

❤ (@lingliberaty) June 15, 2020

It has been a year since you left us. I remember that you were the first person who said the Five Demands. Hong Kongers never forget. Marco Leung Ling-kit, a fighter for justice, he was pushed to fall by the regime. I can’t forget and will never forget.

Authorities drag feet

Another protester, Chow Tsz-Lok, 22, fell from a car park during a riot police operation around midnight on November 8, 2019.

The death was suspicious as Chow was sending out text messages to fellow protesters, containing information about the whereabouts of riot police at the time of his death.

Moreover, he only fell from the third level to the second level of the car park — just a few meters in height. Many believe that he was murdered.

The Coroner’s Court is still yet to launch inquiries into the causes and circumstances of both Leung and Chow’s deaths.

Leung’s father told journalists that Hong Kong police has delayed handing over the investigative report to the court.

Ahead of the anniversary of Marco Leung’s tragic fall, Civil Human Rights Front, a coalition of local non-governmental organizations, urged citizens to commemorate Leung by putting flowers outside the Pacific Place shopping mall.

Thousands answered the call, despite the heavy presence of riot police.

We shall never forget! https://t.co/xGfGZCji2Y

— HK dreamer (@hkfajie) June 15, 2020

15/06

17:20金鐘現場 pic.twitter.com/Ex5ycQvAbw

— 貓婆婆(1) (@chowkinwah2) June 15, 2020

Eventually, the queue grew to such a size that people had to wait for two hours to place the flowers outside the shopping mall.

#hk – the queue to pay tribute to deceased protester Leung Ling-kit extending all the way from Pacific Place to Hong Kong Park pic.twitter.com/nbQdL4tazA

— Lok. (@sumlokkei) June 15, 2020

The crowds outside the mall continued into the early hours of June 16, while pro-democracy district councillors set up temporary memorials in other parts of the city to allow local residents to pay their tributes.

The number one cause for suicide is untreated depression. Depression is treatable and suicide is preventable. You can get help from confidential support lines for the suicidal and those in emotional crisis. Visit Befrienders.org to find a suicide prevention helpline in your country.

Written byOiwan Lam

Protest art in the streets of Tripoli: An interview with Lebanese artist Batool Jacob

Street art during the anti-government protests in Lebanon

Translation posted 29 June 2020

Batool Jacob. Photo taken with permission from her Instagram.

Since the demonstrations against the Lebanese government began on 17 October 2019, street art has increasingly become another form of protest. Artist and activist Batool Jacob, together with a group of artists from Tripoli, took her artwork to the streets as urban art spread across walls in unison with the voices protesting across cities.

Last October, when the Lebanese government wanted to implement a tax on the WhatsApp call service and other social media platforms, thousands of Lebanese people went out to protest in different cities. For them, this new measure disproportionately affected the poor majority. Although the government withdrew the measure, protests continued, denouncing political corruption, the sectarian system that establishes fixed quotas for seats based on religion, the economic crisis, as well as defending the rights of women and minority groups, including Syrians. The government fell on 29 October, but when a new government was formed in January 2020, it was received with fresh protests. Since the protests began, the government detained more than 450 people, many of whom have reported being tortured.

The city of Tripoli and its northern area, home to a predominantly Muslim population, played a central role in the protests. Previously these areas had experienced a lack of media coverage, and so protests in Tripoli have also contributed to erase stereotypes related to poverty and instead highlighted the community's artists, spokespeople, youth, and the unity of its people.

Within this context, GV author Marta Closa Valero interviewed Batool Jacob, a self-taught artist from Tripoli. Batool, who painted street-art during the protests in 2019, now continues to make art from her home as the country eases the lock-down due to COVID-19.

Marta Closa Valero: Many works made by Lebanese artists can be found on social media related to these protests, such as the cultural arts space “Art of change ” in Beirut. You have done similar work in Tripoli, how has this movement emerged?

Batool Jacob: Street art is a new technique for me, the first job I did was in January together with my friends Ghiath Al Robih, a Syrian Palestinian artist living in Tripoli, and Nagham Abboud, also a Tripoli artist. It's interesting because its the first time in the city that a group of artists have come together for a common cause, to show the revolution and to fight for freedom of expression. Before, each area had its own art exhibitions but there wasn't unity.

“The fall of the Lira”, by Batool Jacob, Ghiath Al Robih and Nagham Abboud. Photo by Joao Sousa, used with permission.

MCV: What was the motive for doing the first artwork together? What did you want to show?

BJ: The work was mostly Ghiath's idea. It consisted of a 3D painting on the ground in the square of the Tripoli revolution. We represented the Lebanese pound falling into the abyss. It is a simple way of portraying what we were living through in real time, we were losing the value of state currency without the government doing anything to save the situation.

MCV: Individually and with the group, what are the main themes that you want to transmit through your work?

BJ: Our main topic is the revolution, to show how people are oppressed and the harsh conditions that we live in, the Lebanese government does not provide us with basic rights. For this reason, as artists we are looking to do something that cannot be underestimated, that is, we want to put on record the demands of the protests and ensure that our voices are heard. We don't want to lose our right to express ourselves, we have a responsibility to do everything that we can to express our message.

Photo credit to @pixmotion in the Instagram account of Jacob. Used with permission.

MCV: Considering that the street is a masculinized space, have you ever felt that it is more difficult to make street art as a woman?

BJ: Being a woman and wanting to make street art or any other artistic discipline that involves performing on the street is more difficult for a woman. In Lebanese society there are different mentalities, and oppression towards women does exist. Society thinks of women as being confined to the home, cooking and taking care of children. In this way our outlook diminishes considerably. It is this mentality that does not accept a woman on the street painting or performing other forms of art, such as dance. As a woman you are allowed to make art at home and then take it to a gallery, since it does not carry negative consequences because there is no public display. However, when it translates into street art, there is a public exhibition and then you can find yourself in negative situations, with lewd eyes, intimidation and people with a bad opinion of you. This leads many women to not make the leap to street art. Despite these aspects, I would like to give courage to all Lebanese women to take to the streets and carry their skills with them.

Photo from Jacob's Instagram. Used with permission.

MCV: These last weeks have seen protests in Tripoli again. What was the motive for the protests and what is your position as an artist and activist?

BJ: The latest protests have emerged as a result of the rapid increase in the cost of living, the prices of basic products have increased a lot. People no longer have anything to lose, so they are projecting their anger towards the banks, since they are at the top of the institutions that rob the citizens. Personally, I do not think that this reaction is favorable to recover our money. I do believe in the union of the entire Lebanese population to put pressure on the government and to stifle this chaos.

Photo credit @ahmed_photo86, shown Instagram account of Batool. Used with permission.

MCV: Seeing the current situation in Lebanon, what is your position with regards to the future?

BJ: The current situation does not make me feel good for the future. I want to have hope but reality shows us that the situation is getting worse. The surge of COVID-19 cases and the lack of preventative measures on the part of the people can make the situation even worse. Despite this, I wish Lebanon freedom and stability, with my art I will continue to do as much as I can to help raise awareness and transmit the messages of our protests.

Written byMarta Closa Valero

Translated byClara Guest

Israel appoints its first Ethiopian-born minister, Pnina Tamano-Shata

Ethiopian Jews still struggle for acceptance in Israeli society

Translation posted 8 June 2020

Portrait of Pnina Tamano-Shata, used under license under CC BY-SA 3.0

Israel has just appointed its first black minister, Pnina Tamano-Shata, from the Ethiopian Jewish community. Despite this encouraging gesture, the community still faces discrimination and racism in Israel.

It has been a remarkable journey for Tamano-Shata, who was appointed minister of immigration and integration on May 1, 2020. Born in Ethiopia, in what's known as the Falasha or Beta Israel community, she spent her first few years in a refugee camp in Sudan.

At the age of three, she was repatriated to Israel as part of a clandestine transfer operation organized by Tel Aviv with the support of Washington, known as Operation Moses. She was among 7,000 Ethiopian Jews who arrived in Israel between November 20, 1984, and January 6, 1985.

Once settled in Israel, she integrated well into society, studied law and worked as a journalist and lawyer. She also became involved in civil society groups, becoming vice-president of the National Association of Ethiopian Students in 2004, and a member of the executive committee of Transparency International from 2015 to 2018.

She then started a political career and was elected to the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, where she served as a representative of the secular party, Yesh Atid, from 2013 to 2015.

Her social and political commitment earned her recognition in Israel as well as abroad. In 2016 she won the Unsung Award prize, awarded by the Drum Major Institute, an American nongovernmental organization that fights for human rights and racial equality.

The ultimate recognition came in May 2020 after she was reelected to Knesset on March 2, then appointed minister of immigration and integration. When asked about her appointment, she said:

Translation

Original Quote

I am delighted and proud to take on the role of minister of immigration and integration. For me, it is a landmark and the closing of a circle for this 3-year-old girl who immigrated to Israel without a mother, crossing the desert on foot; growing up in Israel, and in the struggles that I have led and that I still lead for the community, integration, acceptance of others and against discrimination and racism; up to my public mission inside and outside the walls of the Knesset and today to the role of minister of immigration and integration.

Immigration is the beating heart and soul of the State of Israel. I will work diligently to encourage immigration from countries all over world and to lead the reform of the immigrant absorption process in Israel.

The other side of the coin: Institutional racism

Even though Tamano-Shata is optimistic, the situation of black people in Israel remains difficult, given that the Ethiopian Jewish community, estimated to have more than 130,000 members or 2 percent of the population, is still subjected to racism. As this article recalls, numerous scandals bear witness to widespread racism against black people, of which Tamano-Shata herself was a victim:

Translation

Original Quote

In 1996, during a nationwide collection campaign, the Israeli blood transfusion centre threw away all the donations from Ethiopian immigrants for fear that they may be carriers of AIDS. Humiliated and angry, the Ethiopian Jewish community organised a huge rally in Jerusalem outside the Prime Minister's office, which descended into clashes with the police.

However, these clashes did not lead to any changes. In 2013, whilst Tamano-Shata was a member of parliament, she decided to donate blood as part of a donation campaign organised by the Magen David Adom [Israel's national blood bank service] within the parliament building in Jerusalem. An official from the organisation was filmed on camera explaining to Tamano-Shata that “according to the Ministry of Health's guidelines, it is not possible to accept blood of Ethiopian Jewish origin”. The MP protested during an interview on the private television channel 10 against ‘this affront to an entire community based on the colour of our skin.’

Another far-reaching scandal was that the forced contraception of Ethiopian women that was revealed in 2013, as this article explains:

Translation

Original Quote

For five years, the government denied that it had implemented a contraceptive system for Ethiopian immigrant women, forcing them to accept an injection of the contraceptive agent Depo-Provera if they wanted to enter Israeli territory.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI) called for an investigation and an end to these injections. The director general of the Ministry of Health ordered for these contraceptive injections to stop. The Ethiopian Jews or Falashas are Israeli citizens and have long been segregated from other Jewish communities.

Another example of the violence and racism suffered by the Ethiopian Jews is the case of Damascus Pakada, an Israeli soldier born in Ethiopia. One day in April 2015, he was returning home in military uniform to celebrate his birthday. He was arrested and beaten by two police officers and, for no reason, thrown into prison.

Thanks to video footage of the incident, he was later released from prison and the police officers were arrested on suspicion of excessive use of force. This incident provoked demonstrations by the Ethiopian Jewish community. Pakada was later honored by the army and received by the prime minister.

At the time, President Reuven Rivlin admitted that Israel had committed serious errors that had traumatized Jews of Ethiopian origin:

Translation

Original Quote

The protesters in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv have revealed an open, bleeding wound in the heart of Israeli society. We must directly address this open wound. We have made mistakes, we did not open our eyes enough and we did not listen enough.

Despite these scandals and the statements from Rivlin, anti-Falasha and anti-black racism continue, as reported in July 2019 by the French union activist, Pierre Lemaire:

Translation

Original Quote

Since 1997, eleven black Israelis have died during confrontations with the police. According to the Association of Ethiopian Jews, prosecutions of Israeli-Ethiopians have increased by 90% since 2015. What's more, 90% of young black people who appear in court are convicted, compared to only a third of other Israelis.

After the announcement of Tamano-Shata's appointment as the new minister, many Israelis shared their feelings on social media.

For Chely Lobatón,Tamano-Shata's presence is the only good thing about the new government:

Pnina Tamano-Shata getting the Aliyah and Integration Ministry is one of the few good things about the incoming government. As Israel's first black cabinet member and an Ethiopian immigrant herself, I hope it means easier absorption for African Jews. https://t.co/zu7U5BCiGO

— Chely Lobatón (@chelylobaton) May 28, 2020

Igor Delanoë, from the Franco-Russian Observatory, notes:

#Russie-#Israel /Nouveau cabinet israélien: le ministère de l'Aliyah et de l'Intégration échoit à Pnina Tamano-Shata, d'origine éthiopienne. Jusqu'à présent, ce portefeuille revenait à une personnalité politique russophone. Par ailleurs, un nvl ambassadeur devait ê nommé à Moscou

— Igor Delanoë (@IgorDelanoe) May 18, 2020

#Russia- #Israel / New Israeli cabinet: the Ministry of Aliyah (Immigration) and Integration passes to Pnina Tamano-Shata, of Ethiopian origin. Until now, this portfolio belonged to a Russian-speaking political figure. In addition, a new ambassador should be appointed to Moscow.

Ironically, the former minister of immigration and integration, Sofa Landver, who is of Russian origin and Tamano-Shata replaced, said in 2012, “You should say thank you to us for welcoming you,” in response to a previous wave of demonstrations by young Israeli-Ethiopians.

Written byAbdoulaye Bah

Translated by Emma Dewick

Remembering Amadou Diallo, a Guinean victim of police brutality in the USA

Black Lives Matter protests remind the world of Diallo's plight

Posted 22 June 2020

Amadou Diallo anti-police brutality march in front of the White House, February 15, 1999, Elvert Xavier Barnes Protest Photography via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

The recent surge of Black Lives Matter protests in the United States highlights a long history of police brutality targeted against Black Americans.

On May 25, George Floyd, a Black man, was killed by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Since his death, protesters and activists have taken to the streets, speaking out the names of countless others who have died at the hands of the police, including the assassination of young Guinean Amadou Diallo who came to the USA to study.

Diallo, 23, was brutally shot 41 times at the entrance of his apartment on February 4, 1999, by four New York City plainclothes police officers who were part of a now-defunct “street crimes unit.” The four say Diallo was a rape suspect and that they thought he had a gun on him — he was only carrying his wallet, however.

The four cops, Edward McMellon, Sean Carroll, Kenneth Boss and Richard Murphy, were all charged with second-degree murder, but were all acquitted — as is often the case that police benefit from total impunity in American courts. This acquittal enraged many Americans of all races and led to national protests.

Police officer Boss remains on the police force but was “reassigned his gun” in 2012. Officer Carrol offered an “emotional apology” to the family, but not until much later, according to writer Janus Marton.

New York “has been the world’s greatest experiment in multiculturalism for centuries, drawing ambitious people with dreams and talent from across the country and the world to its five boroughs,” recalls Marton, who remembers how the four officers’ trials took place in Albany, a nearby city, because of concern that they “could not obtain a fair trial in the Bronx,” the New York City borough where Diallo was killed.

Decades after Diallo's murder, Black Lives Matter protesters remember the circumstances of his brutal killing by New York City police officers, citing New York Governor Andrew Cuomo for his passivity on police accountability.

Jesse McKinley, Albany bureau chief for the New York Times, wrote:

NEW: Families of victims of NYPD police killings – Amadou Diallo, Ramarley Graham, Kimani Gray, among others – issue scathing letter to @NYGovCuomo, saying he has been “one of the most consistent obstacles” to police accountability.

Letter here: https://t.co/oFTSof5SE3

— Jesse McKinley (@jessemckinley) June 15, 2020

Amadou Diallo anti-police brutality march in front of the White House, February 15, 1999, Elvert Xavier Barnes Protest Photography via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Who was Amadou Diallo?

Diallo was born in Liberia to Guinean parents, Saikou Diallo and Kadiatou Diallo, as the oldest of four, explains Ayodale Braimah, an African writer. His parents exported gemstones between Africa and Asia, giving Diallo the chance to study in various countries, including Thailand, where he lived for a time with his mother after his parents divorced.

Kadiatou Diallo, Amadou's mother, is a fighter who married at the age of 13 and was pregnant with Diallo at 16. She educated herself and started a business in Thailand.

As an English student, he was drawn to American culture. In 1996, Diallo followed his family to New York City and started a business with a cousin. He worked for a while as a street vendor with aspirations to study English and computer science.

A grieving mother, a grieving city

Kadiatou Diallo, Diallo's mother, was in Guinea when she received the news that her son had been shot by police officers. She traveled to the USA and started fighting for his memory, becoming “a symbol of the struggle against police brutality” in the United States who uses her experience to empower others, wrote Charisma Speakers, a blogger.

“Mrs. Diallo humanizes the tragedy of racial profiling and police brutality and continues to aggressively work with community leaders to bring about change,” Charisma Speakers continued.

The Diallo family sued the New York Police Department in a $61 million wrongful death lawsuit and eventually settled for $3 million, according to Alexander Starr with Public Radio International, who wrote about the legacy of Diallo's killing in 2014, on the fifth anniversary of his death: “They used some of that money to create the Amadou Diallo Foundation and scholarship fund in 2005,” and students continue to receive scholarships until today.

On the fourth anniversary of Amadou Diallo's death, New York City unveiled a sign for Amadou Diallo Place in the Bronx to honor his memory.

Kadiatou Diallo has worked with 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care, a legal advocacy group to improve policing in New York City, and has also worked with local politicians to pass a racial profiling law in Albany, New York.

In 2004, Kadiatou Diallo wrote an award-winning book called, “My Heart Will Cross This Ocean: My Story, My Son, Amadou.” She was featured in the documentary, “Death of Two Sons,” in 2006, and “Every Mother’s Son,” about three mothers who each lost an unarmed child at the hands of the New York Police Department.

Diallo's tragedy has inspired more than 20 songs, five docuseries and two films.

Black Lives Matter today

The Black Lives Matter protests that erupted in response to George Floyd's murder by police prompted many Twitter users to invoke the name of Amadou Diallo, over 20 years since the brutal killing.

Clara || BLM (@quiteclara) recommends a docuseries on Diallo's case:

Netflix's docuseries “Trial by Media”, ep.3 “41 Shots”.

4 NYPD officers in 1999 shot 41 shots at Amadou Diallo, 19 of which struck and killed him, outside his apartment. Diallo was unarmed. All 4 officers were charged with second-degree murder, but all 4 were found not guilty.

— clara || BLM (@quiteclara) June 16, 2020

Clint Smith, a writer and teacher, tweets “enough is enough”:

I’m old enough to remember AMADOU DIALLO and ABNER LOUIMA. Enough is enough. More than 20 years later we have not turned the page. Stop telling black people what they should have done or what they should do to not get killed. It’s the other way around.

— Marla Wolfson (@marla_vous) June 15, 2020

So African (@Mx_chichi), an anthropologist, writes:

This is the same New York police that promoted Kenneth Boss of of the men who killed Amadou Diallo. After shooting Diallo 41 times & bullets hitting his body 19 times. The NY cops involved were never held accountable. They said “bas! Tumesema sorry!” & They were “forgiven” https://t.co/ObcCcrVU9u

— So African (@Mx_chichi) June 10, 2020

Felonious Munk, an Ethiopian American comedian, writer and actor, recalls the names of other Black American men who were killed at the hands of police in the United States:

Obama was president when Mike Brown, Eric Garner, amd Tamir Rice we're killed. Clinton was president when Amadou Diallo (and countless others) were killed. Who do we vote for to get them to stop killing Black people with impunity? https://t.co/BNUblvl3E9

— Felonious Munk  (@Felonious_munk) May 30, 2020

(@Felonious_munk) May 30, 2020

Written by Abdoulaye Bah

Nina Paley's ‘Seder-Masochism’ Film Explores Patriarchy in the Book of Exodus Through Animated Ancient Idols

Screenshot from the song sequence “You Gotta Believe” by Nina Paley on Vimeo.

Global Voices interviewed American free culture activist and filmmaker Nina Paley about her new animated film “Seder-Masochism.” It is loosely based on the Book of Exodus from the Torah/Bible and exposes the veiled patriarchy in the religious text.

Creative Commons licenses

Creative Commons (CC) licenses are a set of licenses that facilitate the sharing of creative works. The CC0 license is the most open of all the licenses, and allows users to use, share, and make derivatives, and use the original/derivative version for even commercial purposes without any attribution. On the other hand, Creative Commons Non-Derivative Non-Commercial CC-BY-ND-NC is the most restrictive of all CC licenses and is close to “All Rights Reserved”.

Paley is the director of the 2008 full-length animated film “Sita Sings the Blues” which she released to the public domain in 2013. The film narrated the Indian epic poem Ramayana by using the 1920s jazz songs of Annette Hanshaw. It brought Paley worldwide fame because of its feminist interpretation of the epic and her long battle against the copyright claims tied to the songs of Annette Hanshaw used in the movie. Paley had to pay a negotiated amount of at least US$50,000 by loaning the sum. She eventually reclassified the film’s license from Creative Commons Attribution-Share-alike 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-SA 3.0) to Creative Commons CC0 (equivalent to public domain).

In an interview with Jewish podcast station Judaism Unbound, Paley said that “Seder-Masochism” is her take on the Exodus, which she first learned during Passover Seders. The Passover Seder is a Jewish ritual that involves the retelling of the liberation of Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt. She added in the interview that “she identifies herself as a “born-again atheist” and explains the ways in which her recent study of the Book of Exodus has left her uncomfortable.

Several songs and scenes from the film “Seder-Masochism” have been uploaded by Paley to the Internet including the song sequence “You Gotta Believe” which turns Minoan stone goddess idols into flash animation. It features Moses and “singing” ancient goddesses who find themselves about to be defeated by patriarchy.

Global Voices reached out to Paley to learn more about her second film.

Subhashish Panigrahi (SP): First of all, congratulations on your upcoming work. What are the roles you're playing in the entire production? What is the movie about?

Nina Paley (NP): Once again I'm producing, directing, writing, animating, everything-ing…I'm hoping the sound designer for “Sita Sings the Blues“, Greg Sextro, is able to do more sound design for Seder-Masochism. The music is all “found” and used without permission [at the moment]. Much or all of my use is Fair use, but ultimately that can only be determined in court.

Seder-Masochism is about the Book of Exodus from the Torah/Bible, and indirectly the Quran (Moses is a prophet of Islam). My interpretation of Exodus is that it's the establishment of complete patriarchy, the elimination of any remaining goddess-worship from older times.

Some of clips from the feature-in-progress are here.

SP: What inspired you to start this project?

NP: Sita Sings the Blues was denounced by fundamentalists who called my collaborators “self-hating Hindus.” As a Jew, that rhetoric was familiar to me – Jews *invented* that “self-hating” nonsense. Since I'm not a Zionist, I've been called a “self-hating Jew” too. Also, the Hindutvadis called me a “white Christian woman who hates Hindus”, and sent hate emails saying “how would you like it if someone made a film about YOUR religion?!” Of course I love it when someone makes a good film about Abrahamism - Monty Python's Life of Brian is the best I can think of. I was (am) also frequently accused of “cultural appropriation“, implying that only those of Hindu/Asian descent are qualified to work with Hindu/Asian stories. So it seemed that everyone, right and left, wanted me to make a film about “my” religion, Judaism! I figured if they're offended by Sita Sings the Blues, they'll be REALLY offended by that. I printed up a Jew Card so I could “play” it for this project.

Ancient goddess LILITH gif by Nina Paley.

Source: Nina Paley/Wikimedia Commons

SP: The song is hilarious! How did you bring the thousand-year-old stone idols to life?

NP: There are already goddesses in the Flash sections of Seder-Masochism I animated a couple of years ago. I needed to put more “goddess” into the film, and was tediously redrawing the Flash goddesses in Moho, the software I'm using now. It occurred to me that instead of redrawing them I could use the source images they're based on, I spent a few days finding the highest resolution images I could, and a few more days manually removing the backgrounds in GIMP. Moho can do things Flash can't, such as this type of animation with raster images. Anyway, they looked cool so I'm using them in the remaining Seder-Masochism scenes.

The goddesses in flash animation can be downloaded on Wikimedia Commons.

As Paley is producing the film on her own, she is also working with other free culture activists like the United States-based nonprofit QuestionCopyright.org to raise funds, apart from launching a Kickstarter campaign. She is uploading segments of the film publicly on the Internet as the film is being developed.

A previous version of this article incorrectly identified the origin of the goddesses. They are Minoan, not Egyptian.

Posted 4 February 2018

Written by Subhashish Panigrahi

Written by Qurratulain (Annie) Zaman

Post-crisis hackathon: Ecuadorian NGOs crowdsource for a world after COVID-19

Nearly 550 people registered and 16 ideas are receiving support

Translation posted 11 June 2020 14:43 GMT

Hackathon. Photo from Andrew Eland/Flickr, under CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

This story was initially published on the Ecuadorian site Ojo al Dato (Eye on Data) and then republished and edited by Global Voices. Here are the first and second articles in the original series.

Many countries are slowly starting to emerge from lockdown and they are being forced to confront the hard realities of a world with COVID-19. In Ecuador, a country hit hard by coronavirus, NGOs organized a hackathon in April to crowdsource project ideas that would address some of these realities. On May 30, the winners were announced via a live YouTube broadcast, bringing public exposure as well as funding prizes to the successful projects.

Crowdsourcing the fight against coronavirus

In late April, Ecuador had the third-highest number of registered cases in Latin America; and at the time of writing, official figures reported 3,642 deaths.

Launch image, photo from Estéfano Dávila, for free media use.

The Post-Crisis Hackathon, which took place from April 29-30, was attended by 549 people who brainstormed solutions to the issues that would affect the economy and society in a post-COVID Ecuador. Hackathons are collaborative spaces that seek solutions to specific challenges and this one focused on challenges related to ten areas: environment, work and employment, daily life and social practices, cultural industries, education, health and well-being, economy and production, and government and citizenship.

The event was organized by developer and sociologist Iván Terceros along with his colleagues from MediaLab (connected to the NGO CIESPAL) as well as various organisations and business networks. In an interview with Ojo al Dato, Terceros spoke about the motivation behind the event:

Translation

Original Quote

It is not clear what will happen the day after the crisis […] It could be that those are the most critical moments [for society].

Hackathon projects making change

The participants shared 116 projects and organizations participating in the Hackathon helped choose 19 finalists.

There were two votes: one from the public — which elected WiyaPoint and ChasquiCheck as winners of the public's vote — and one of from the jury. Nearly all the finalists received prizes.

WiyaPoint's mobile app addresses the use of plastic bags — a contamination point for COVID-19 — by rewarding users every time they turn down a plastic bag when making a purchase. ChasquiCheck seeks to address misinformation around COVID-19 by setting up a digital platform to verify, identify and classify information to combat false news.

The WiyaPoint app will receive exposure, campaign launch, and social media advertising for a value of $1,000 provided by crowdfunding platform Green Crowds. ChasquiCheck will also receive the same amount of help to launch its virtual platform, thanks to the association of risk management professionals in Ecuador.

Fourteen other projects received some form of prize from the jury's vote. For example, participants thought of self-sustaining gardens as a response to a possible food shortage due to the pandemic. Both Grupo Faro and Incubadora La Libertad will offer them technical advice for a value of $1,000.

Todos Más Cerca is a digital platform connecting small and medium businesses to help them reactivate their economy. Through the platform, businesses can offer their products to users who are geographically nearby; the goal is to avoid agglomerations that could increase the number of COVID-19 infections. Todos Más Cerca already has agreements with Chambers of Commerce in parts of Ecuador, such as Zamora, Loja, Cuenca, among others.

The project will also receive a fund of $3,000 from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the La Libertad Incubator. The economic promotion agency Conquito will provide them with accompaniment, advice and mentoring.

In the case of Ecuador, Terceros explained that MediaLab will continue to support the projects that have been brought to life, so that they can be incubated as start-ups throughout the year.

Written by Carlos Flores

Translated by Kitty Garden

Information warfare: COVID-19’s other battleground in the Middle East

The internet breeds and amplifies state-sponsored fake news and propaganda

licensed under CC BY BY-SA 2.5

COVID-19 has exacerbated existing political tensions in the Middle East and North Africa, a region already marred by decades of conflict. Now, unscrupulous politicians blame their political enemies or neighboring governments for the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Director of the World Health Organisation (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, sounded the alarm on the threat that mis- and disinformation poses to humanity:

“At the WHO, we’re not just battling the virus, we’re also battling the trolls and conspiracy theories that undermine our response,” he said, reiterating that false information can cause confusion and fear.

The MENA region is no stranger to conspiracy theories and disinformation practices. A 2019 Oxford University study revealed that the region is home to half of the top 12 countries identified as having a “high cyber troop activity” — including Egypt, Iran, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and the United Arab Emirates.

Those in positions of power use “information warfare” to frame narratives and control public opinion, and social media has become the main battlefield to employ influencers, trolls, bots, and commenter armies.

In Iran, Yemen and Syria, the so-called “axis of resistance” — whose legitimacy is often tied to virulent opposition to the West — leaders have seized on COVID-19 to reaffirm political positionality and channel hostile anti-Western ideologies.

Hezbollah, for example, has framed the coronavirus as a plot twist by their “enemies” — the West in general and the United States in particular. Hezbollah, a Shi’a political party based in Lebanon, and affiliated with Iran, is known for being a state within a state. It is considered a terrorist organization by most countries.

In March, Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah affirmed:

The corona is a highly threatening enemy. We have to confront this invasive enemy. We should not surrender or despair or feel helpless. The response must be confrontation, resistance, and fighting. We will win this battle. It is only a matter of time.

The Iranian-led ‘axis of resistance’

In the battle for hearts and minds, the Iranian regime’s ideological army — the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) — has led a counternarrative about the pandemic, portraying the virus as a conspiracy orchestrated by the regime’s traditional enemies — the United States and Israel.

The propaganda includes claims that the virus is an “American biological invasion” and a “Zionist biological terrorist attack,” leading some of the regime’s defenders to call for a retaliatory response.

Since its founding in 1979, the IRGC has been the “ruling clergy’s principal mechanism for enforcing its theocracy at home and exporting its Shi’ite Islamist ideology abroad, “according to Foreign Policy.

It collaborates with its allies in Arab capitals where it holds considerable influence — Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen. They share similar anti-Western, US and Israeli ideologies. The leaders of these nations often glorify fighting and martyrdom.

Hezbollah Secretary-General Nasrallah, for example, regularly preaches martyrdom messages to his base. In an interview, he explains: “Our fighter blows himself smiling and happy because he knows he is going to another world. Death for us is not the end but the beginning of real life.”

Houthi: Iranian proxy voice in Yemen

Yemen continues to grapple with the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, according to the UN, after plunging into a bloody proxy war in 2015, when a Saudi-led coalition intervened to remove Houthi leaders from power taken following a coup.

Houthis forces, backed by Iran, control the most-populated northern region, as well as the media. Houthi leaders have used the pandemic — described by some analysts as a “gift for the Houthis,” to attack rivals and deflect attention from the ongoing crisis. Houthi leaders also promote the Iranian regime’s conspiracy theory that the virus is an American plot.

Houthi Minister of Health Dr. Taha Al-Mutawakkil said in a public sermon aired on TV: “We must ask the whole world, we must ask all of humanity: Who and what is behind the coronavirus?” He concludes with a Houthi slogan: “Death to America! Death to Israel! Curse be upon the Jews! Victory to Islam!”

As the virus sweeps through Yemen in recent weeks, activists report dozens of deaths. Houthis leadership has denied the scale of the outbreak and downplayed its severity. In a press conference, Mutawakkil said:

We should not do like the rest of the world who have terrorized the population. The recovery of the virus is very high, it is in Yemen of over 80 percent. The treatment of the coronavirus will come from Yemen.

Houthis often conform to an ideology rooted in victimization and showcase that all of Yemen’s problems are caused by external interventions that started in 2015 with the Saudi-led military campaign. As such, they often blame the Saudi-led intervention that absolves them responsibility for the current crisis.

Mohamed Ali al-Houthi, a member of the Houthi Supreme Political Council, tweeted on March 16, that the Saudi-led coalition is to blame for any spread of coronavirus in Yemen.

وتتعمددول العدوان في المناطق التي تحتلها على عدم اتخاذ أي إجراءات إحترازية ولا طارئة ولا حجر صحي ولا أي شيء

وكان لا وباءيجتاح العالم يسمى #كرونا

نحمل العدوان الأمريكي وحلفائه مسؤلية أي حالة باليمن_فهويسيطر على الأجواء والمنافذ البحرية البرية_

ومسؤلية عدم التأهيل واتخاذ الإجراءات

— محمد علي الحوثي (@Moh_Alhouthi) March 16, 2020

In the territories occupied by the aggressor countries [Saudi led coalition] no precautionary or emergency or quarantine measures have been taken or anything. There would not be an epidemic sweeping the world called corona. We hold the American aggressor and its allies responsible for every case in Yemen, as it controls the airspace, the land and ports.

Houthis leaders have also exploited the virus to push their base into action and boost military recruitment. On a Houthi affiliated TV channel, a speaker recommended the public to join the battlefield and die as martyrs instead of dying confined at home from the coronavirus.

The Saudi-UAE axis: Blame it on Qatar and Iran

The Gulf Council Countries (GCC) was formed in 1981 in the wake of the Islamic Revolution in Iran and the Iran-Iraq war, by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman and Bahrain. Their union, from its inception, was to defend themselves against an Iranian threat.

However, the GCC has been in crisis since 2017, when a bloc of countries led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, came into conflict with Qatar over allegations of links with Iranian’s “terrorist groups.” A full blockade has been imposed since June 2017 against Qatar.

The coronavirus has been politicized against this backdrop. A widespread narrative in all GCC countries supports the story that the virus was imported from either Iran, the regional epicenter of the crisis, or Iraq, via Shi’a citizens returning from a pilgrimage in Iran.

The Saudi daily newspaper, Al Jazeera, accused Iran of “adding to its bloody terrorism health terrorism” for not having been transparent and allowing the virus to spread.

Saudi Arabia held Iran “directly responsible” for the spread of COVID-19 and Bahrain accused it of “biological aggression” by not stamping passports of Bahrainis who traveled to Iran.

In a region ruled by Sunni royal families over a large Shi’a minority, scrutinized for its perceived proximity with Iran, this scapegoating is likely to fuel sectarianism and tension.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia have launched social media campaigns to blame Qatar for the coronavirus using hashtags such as #Qatariscorona, claiming that Qatar manufactured the virus in China to jeopardize Saudi Vision 2030 and Dubai Expo 2020.

The internet has provided fertile ground for breeding and amplifying state-sponsored fake news and propaganda campaigns. In an era of social distancing and increased reliance on social media, allowing these narratives to spread unchallenged and unpunished undermines an effective pandemic response — and more widely — peace and democracy.

Written by Saoussen Ben Cheikh

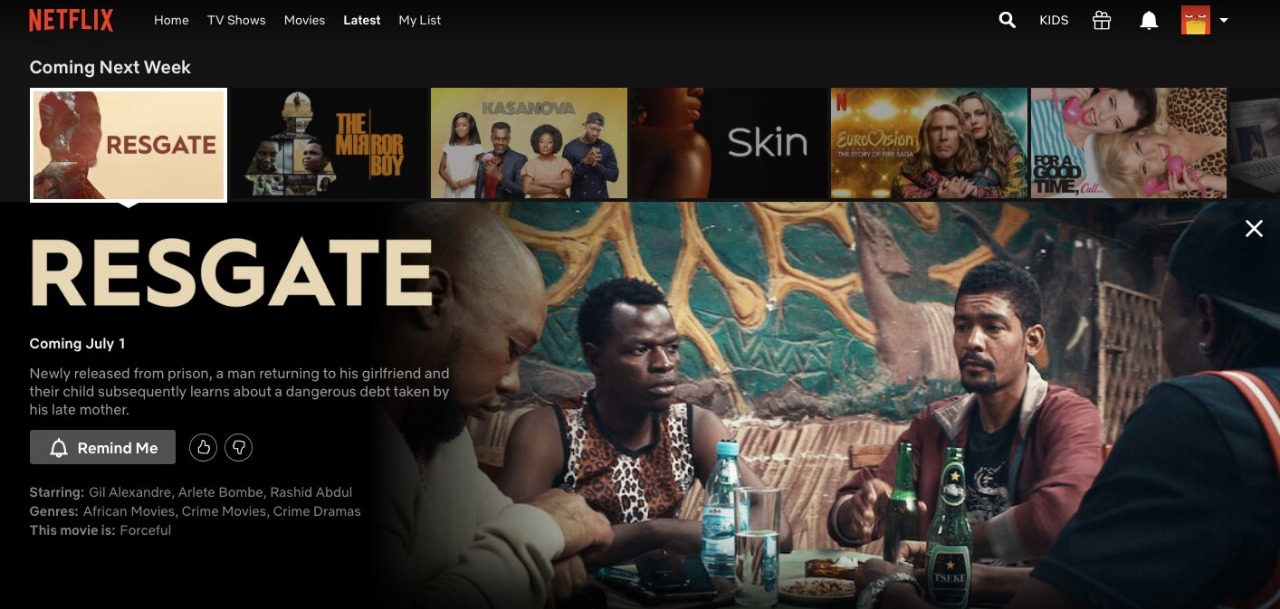

Netflix picks up ‘Resgate,’ the first Mozambican film to appear on the platform

African productions are gaining traction on Netflix

Translation posted 29 June 2020

Resgate (Redemption) featured on Netflix (screenshot by Dércio Tsandzana).

For the first time, a Mozambique-made independent film will be shown on Netflix. The feature film “Resgate” (translated in English as “Redemption”) was written and directed by Mickey Fonseca, who is from Mozambique, and will premiere on the platform in July.

“Resgate” was partially financed via crowdfunding and was filmed in Mozambique in 2017. The film's plot was summarized by the Portuguese newspaper Público:

Translation

Original Quote

Resgate focuses on the story of Bruno. After spending four years in prison, Bruno wants to change his life and finally get to know the baby daughter he shares with Mia.

He tries to find work as a mechanic, a job he is familiar with, and is initially unsuccessful. Eventually his aunt, who is the sister of his recently-deceased mother, gets him a job in a garage.

But Bruno's new life is unexpectedly blown apart when the bank threatens to evict him from his mother's house if he does not pay back the loan that she, unbeknownst to him, took out before she died. He then returns to a life of crime.

Resgate had a commercial cinematic release in Mozambique, Angola, and Portugal in 2019. It was also shown at festivals in Burkina Faso and Zimbabwe.

In the same year, the film won the Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMA Awards) for Best Screenplay and Best Production Design. The awards are held annually in Nigeria and are the most prestigious in the world for African cinema. It was also awarded the Courageous Film Award at the Film Fest Zell in Austria.

Fonseca told the Mozambican Ministry of Culture that he feels honoured to see his film broadcast by one of the biggest online streaming services in the world:

Translation

Original Quote

Resgate was really well received on a national level, which was exciting for us because we sacrificed a lot and used our own means to make the film. We're bringing the film to the rest of the world in an accessible way.

The film will be available on Netflix with English dubbing, which was well-received on Mozambican Twitter:

💣 BOAS NOTÍCIAS! 💣

A NETFLIX decidiu avançar com a dobragem do RESGATE para língua inglesa, para que o filme tenha maior alcance mundial! 🤩🖤🎬

O lançamento do RESGATE na plataforma de streaming irá acontecer em Julho, mas não no dia 01.

Atentem às novidades! pic.twitter.com/UoKUTSsGUm

— Resgate (@Filme_resgate) June 23, 2020

GREAT NEWS! NETFLIX gave the go-ahead to dubbing RESGATE in English so the film can reach a wider global audience!

RESGATE will be released on the streaming platform in July, at some point after the 1st of the month. Look out for updates!

Todos estamos felizes por ter resgate no Netflix

Nós podemos fazer parte duma revolução artística, imaginem todas outras indústrias a crescer, música, artes visuais etc. Acreditem na nossa arte, temos muito a oferecer e vocês só tem de acreditar e dar UMA CHANCE. Não é difícil

— MICHALUK 🥑 (@Michaluk_) June 18, 2020

We are all happy that resgate is on Netflix.

It allows us to be part of an artistic revolution! Just imagine how other industries will evolve – music, visual arts etc. They believe in our art and we have a lot to offer, so all you have to do is believe in us too and give us A CHANCE. It's not hard.

African productions have recently been featuring more prominently on Netflix. The selection includes the South African series “Queen Sono”, which is the first Netflix original series to be produced entirely in Africa.

Other African highlights in the platform's catalogue are the cartoon “Mama K's Team 4“, which is also South African, and Nollywood classics such as “Lion Heart” and “Chief Daddy”.

Written by Dércio Tsandzana

Translated by Ayoola Alabi

Mozambicans take to social media to piece together the truth about the Cabo Delgado attacks

Attacks by armed groups started in 2017

Translation posted 11 June 2020

Cabo Delgado bridge, Mozambique. August 4, 2009. Photo by F. Mira via CC BY-SA 2.0.

Twitter users in Mozambique are mobilising to share information on the violence in the province of Cabo Delgado, which has been the site of attacks by armed groups since 2017.

Since the start of the attacks, more than 900 people have been killed. In February this year, a local government report revealed that over 150,000 people had been affected by the conflict. The reason for the attacks is not completely clear, but there is some evidence that they are linked to an Islamic extremist group.

Read more: New video gives clues about motives behind attacks in northern Mozambique

In mid-May, the Mozambican government joined other presidents from southern Africa at a high-level conference in an apparent attempt to generate external support for the fight against insurgency.

Days later, the president of Mozambique announced the death of two of the leaders behind the attacks in the north.

Many of the attacks have subsequently been revealed in videos and photos on social media, sometimes by the attackers themselves. In the absence of adequate information from the authorities, some users are trying to make sense of this content on social media:

#CaboDelgado as coisas pioram dia após dia, #massacres atrás de massacres, destruição de vilas umas das outras. Para quando o apoio militar da #SADC ?🤔

#CaboDelgado the situation is deterioriating day after day, #massacre [HYPERLINK] after massacre, destruction of one town after the next. How long until military assistance from the #SADC?

— Egídio João (@Egidio_E_Joao) June 3, 2020

Afinal o que está acontecer em Cabo Delgado (Moçambique)?

After all of this, what is happening in Cabo Delgado (Mozambique)?

A Thread pic.twitter.com/kcVVZDBiTp

— Withney Osvalda (@withneysabino) June 1, 2020

Okok

THREAD CABO DELGADO

Peço que deixem aqui em baixo toda informação que há disponivel sobre o que está a acontecer em Cabo Delgado, vamo nos ajudar a ajudar, invés de reclamarem só!!

Okok

CABO DELGADO THREAD

Please add below any information available on what is happening in Cabo Delgado, let’s help ourselves to help, instead of just complaining!!

— soh fee uh (@smaquile) June 1, 2020

Para podermos ajudar temos que ter informação, e isso o governo não está a publicar, temos que estar a basear-nos em mouth to mouth information e videos fora de contexto que nos mandam de lá…

So that we can help ourselves we need to have information, which our government isn’t publishing, we need to rely on mouth to mouth information and videos beyond what they are giving us…

— druegas, sole da (@Queen_Tassy1) June 1, 2020

Lembrei de ter lido nalgum lugar que a forma mais fácil de roubar terra é criando instabilidade ao ponto dos proprietários fugirem. Não há terra mais barata do que aquela em conflito e miséria. Agora pergunto… a quem interessa comprar Cabo-Delgado?

I remember reading somewhere that the easiest way to steal land is to create instability to the point that owners flee. There’s no land cheaper than where there’s conflict and misery. Now I wonder who would be interested in buying in Cabo Delgado?

— manteiga de karité, bebé (@Leocadeea) June 1, 2020

Some have noted the fact that events outside of Mozambique appear to be receiving less attention than those taking place inside:

Tenho visto em muitos Moçambicanos “Black life’s Matter” e menos “Pray for Cabo Delegado”…

I have seen many Mozambicans with more “Black Lives Matter” and less “Pray for Cabo Delgado”

— 𝗕𝗮𝘃𝘆 (@Djbavy) June 3, 2020

Also being shared are warnings about misinformation:

Mas muita atenção com a informação proliferada por este senhor, já várias vezes foi confrontado por mostrar imagens que não são de Cabo Delgado e ele tenta passar as images como “exclusivas”!

But beware the information shared by this man. He’s already been confronted for showing images that aren’t of Cabo Delgado and he is attempting to pass them off as exclusive!

— Micah Dunduro (@Donduro88) June 2, 2020

A movement has also resurfaced with the aim of organizing solidarity campaign in support of those affected by the escalating violence in Cabo Delgado:

Estamos a preparar a 4a Fase da campanha de solidariedade nacional por Cabo Delgado. Precisamos de voluntários para pré-organização

Por favor partilhem com os vossos amigos que possam ajudar-nos com cartazes e vídeos da convocatória✌🏽#CaboDelgado_também_é_Moçambique#CaboDelgado

We are preparing the 4th phase of the national campaign for solidarity for Cabo Delgado. We need volunteers for the pre-organisation phase. Please share with your friends who are able to help us with poster and video calls to actions #CaboDelgado_também_é_Moçambique#CaboDelgado

— Cídia Chissungo (@Cidiachissungo) June 3, 2020

Quem puder ajudar de alguma forma:#CaboDelgado #CABODELGADOIMPORTA pic.twitter.com/Itnq9V507K

If anybody can help in any way: #CaboDelgado #CABODELGADOIMPORTA pic.twitter.com/Itnq9V507K

— Alícia Cossa (@alicia_cossa) June 3, 2020

Written byDércio Tsandzana

Translated byAyoola Alabi

Tanzanian women’s savings and loan groups in flux during COVID-19

Members struggle to pay back loans and restore group capital

Posted 11 June 2020

A skills training for current and prospective members of vicoba in Dunga, Zanzibar. Photo by Jessica Ott, used with permission.

Editor’s note: Jessica Ott studied women’s civil society organizing in Tanzania. This article is informed by research and fieldwork for her dissertation, “Women's rights in repetition: Nation-building, solidarity and Islam in Zanzibar.”

Vicoba, which stands for “village community banks,” are ubiquitous microfinance savings and loan institutions across Tanzania.

The majority of members are women who rely on vicoba to provide access to credit for business and other living expenses. Women widely describe these groups as a way to reduce their economic dependence on men and enable social solidarity.

Vicoba provide members with credit access during times of financial hardship, but they are not structured to support members during a societal level crisis — such as a drought or a pandemic — when everyone needs to borrow at the same time.

When Tanzania issued a stay-at-home order in March 2020 to prevent the spread of COVID-19 — essentially closing its economy for several months — most vicoba ceased to meet.

The World Bank issued a press release on June 8 that predicts a sharp slowdown of economic growth in 2020 due to COVID-19. Tourism operators forecasted revenue losses of 80 percent or more in 2020, and the crisis could push 500,000 more citizens below the poverty line.

Now, many women members are unable to contribute toward group savings or to pay back loans, which has raised concerns about how vicoba will cope with the long-term financial effects of the coronavirus.

As vicoba members struggle to pay back loans, a decline in group capital has limited the ability of members to borrow, according to a news report in The Citizen.

Women’s participation in vicoba has shifted gender norms and enabled women’s economic agency — to varying degrees — but as groups experience the financial strain of COVID-19, vicoba are in limbo.

An overview of vicoba

Vicoba have operated in Tanzania since the early 2000s. They were inspired in part by a Village Savings and Loan Association (VSLA) model that was first implemented by the Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE) in Niger in 1991.

Before vicoba, women participated in rotating credit associations and informal economic activities in Dar es Salaam at an unprecedented level in the late 1980s and early 90s, according to political scientist Aili Mari Tripp. At that time, Tanzania was transitioning from first President Julius Nyerere’s socialist project of Ujamaa (Swahili: “Familyhood”) and enacting structural reforms to liberalize its economy.

Established during a subsequent era of rapid global microfinance expansion, vicoba have been adapted to Tanzanian cultural contexts. They are usually self-initiated and self-sustaining, unlike borrower groups who acquire credit and accrue debt through formal microfinance banks. Women often establish vicoba with family members, neighbors, friends, and/or work colleagues.

In Zanzibar, the semi-autonomous archipelago off the coast of mainland Tanzania, where the majority are Muslim, many women give their savings groups names that allude to the socialist past or to Islam, like Umoja ni Maendeleo (Unity is Development) and Tunaomba Mungu (We Humbly Ask for God’s Support) groups — both on the island of Pemba.

Individual members buy into vicoba with shares, which enables them to take out loans to support their own business ventures or other living expenses, like health care costs or school fees.

Group members collaboratively determine the amount and terms of individual loans, such as the interest rate and length of repayment. When groups have excess funds, they instigate collaborative income-generating projects with earnings going back to the group.

Vicoba and unity

Vicoba help women meet their own financial needs, but they also enable and strengthen the notion of umoja or “unity,” which embodies ideas of community and mutual support.

A recent Twitter poll highlights the ubiquity of vicoba in Tanzania. Twitter user habimana playfully asked her 18,300 followers:

Mpira – unawaleta wanaume pamoja

Cartoon – zinawaleta watoto pamoja

Nini kinawaleta wanawake pamoja??

— habimana (@uwimano) June 3, 2020

If football brings men together, and cartoons bring children together, then what brings women together?

Over 850 people — mostly men — responded to the poll. The most common, somewhat disparaging response was umbea (“gossip”), closely followed by vicoba and hair salons.

Twitter user Abdulraheem cheekily tweeted:

Wazamani umbea, wasasa vikoba na vikundi vya ushirika

— Abdulraheem (@ibn_sayid) June 3, 2020

For women in the past, it was gossip, but for women today, it's vicoba and other savings groups.

Shifting ideas about gender and household finances

Twitter commentary about vicoba also sheds light on shifting gender norms and household economics in Tanzania.

Twitter user Myra complained to her more than 5,900 followers about the propensity of men to force their wives to wash laundry by hand rather than buying washing machines:

Sema watoto wa kiume mnapenda tu kuwatesa wake zenu na hizi issue za kufua. Washing machine hadi laki 5 zipo. Nasema mke coz kama hujaolewa ukajifanya we dobi utakuwa umeamua.

— 𝓜𝓨𝓡𝓐 (@alwaysmyra) May 29, 2020

Hey, you young men just enjoy persecuting your wives with this issue of hand washing clothes. Even if you have the 500,000 [Tanzanian shillings or $250 United States dollars] for a washing machine. I say ‘wife’ because if you haven't gotten married yet and you do, you will have decided to become a laundry woman.

In response, Twitter user Mgwabi Mwambi challenged Myra for putting too much financial responsibility on men:

Hata watoto wa kike waliiolewa, wanapenda tu kujitesa kufua kwa mikono, washing machine hadi lako 5, wanaweza tu kujibana kwa pesa za VICOBA wakanunua na wala sio kusubiria mume anunue kila kitu.

— Mgwabi Mwambi (@JakaMgwabi) May 29, 2020

Even young women who are married, they enjoy persecuting themselves by hand washing clothes. If a washing machine is about 500,000 [$250 USD], which they can reach with their vicoba savings, then they can buy their own rather than waiting for their husbands to pay for everything.

The Twitter exchange highlights changing ideas and social norms related to the division of household labor and finances in Tanzania — and how vicoba play a role.

Microfinance during COVID-19

The situation in Tanzania points to the vulnerability of microfinance savings and loan groups worldwide when faced with large-scale crises.

During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, restrictions on movement limited women’s economic activities, which drastically reduced the capital of savings and loan groups in Liberia and Guinea, according to a report by the United Nations Development Group.

Several humanitarian agencies have issued emergency measures and guidelines to mitigate the health and economic effects of the coronavirus on microfinance initiatives. CARE, with 357,000 VSLA groups in 51 countries, issued emergency guidelines for supporting savings and loan groups.

The future of vicoba in Tanzania

Some vicoba leaders on Tanzania’s mainland have considered emergency measures like extending loan repayment terms and reducing the interest rates on existing loans, according to The Citizen.

One possible emergency measure may be a government bailout. The Citizen reported that the Ministry of Finance and Planning was conducting a COVID-19 economic impact assessment and would provide recommendations for vicoba and other savings and loan groups. Its emphasis on recommendations, however, suggests that governmental financial assistance may not be forthcoming.

If women default on their loans, group members may decide to liquidate their assets to recoup group debts, which could potentially devastate vicoba and strain social relationships. Members may also decide to accept their COVID-19 related losses.

Vicoba — which provide community, mutual support and human connection — may help women mitigate the financial pangs of the coronavirus.

Written byJessica Ott

❤ (@lingliberaty) June 15, 2020

❤ (@lingliberaty) June 15, 2020

❤ (@lingliberaty) June 15, 2020

❤ (@lingliberaty) June 15, 2020

(@Felonious_munk)

(@Felonious_munk)