NATIONAL REVIEW IS TRYING TO REWRITE ITS OWN RACIST HISTORY

Ryan Grim July 5 2020,

STUART STEVENS, who has gone from running Mitt Romney’s campaign for president in 2012 to a perch as a leading Never Trumper, is out with a new book: his mea culpa of sorts, “It Was All a Lie: How the Republican Party Became Donald Trump.”

Some of Stevens’s former colleagues don’t like it, and one of them, Matthew Scully, savaged it in National Review. “Perhaps the most devastating book review you’ll ever read,” National Review editor Rich Lowry promised.

The review is, to be sure, unfriendly, countering that Stevens is, in so many words, a clown, a hack, a liar, a grifter — and wrong. I’m not here to referee the bulk of their dispute, but one particular claim by Scully in his review merits a closer look.

In his book, Stevens apologizes for his role in propping up a Republican Party he now considers to be little more than a “white grievance party” cynically exploiting racism in the pursuit of power. Scully objects to much of what Stevens has to say in the book, and he zeroes in on Stevens’s claim that, in hindsight, he should have seen all along that Republicans were getting ahead by exploiting racism. Stevens cites the rise of the New Right with Barry Goldwater’s campaign in 1964 straight through to President Donald Trump.

Scully is appalled at such libel upon the GOP, and comes to the spirited defense of Goldwater and one of his chief advocates, William F. Buckley Jr. Buckley was a founder of the National Review and, in many respects, the modern conservative movement, who, Stevens wrote, was simply “a more articulate version of the same deep ugliness and bigotry that is the hallmark of Trumpism.”

William F. Buckley, Stevens wrote, was simply “a more articulate version of the same deep ugliness and bigotry that is the hallmark of Trumpism.”

“As a rule of thumb,” Scully responds in the reportedly devastating review, “anyone so glib and presumptuous as to brush off as ‘ugliness and bigotry’ the enduring political and moral legacy of William F. Buckley Jr. has, for that reason alone, no business involving himself in Republican affairs.”

Scully might want to take a dive through the archives of his own magazine before offering such a definitive judgment. A review of that record shows there is no doubt which side of history Buckley placed himself on. Now, he stands athwart it with Trump, like it or not. Stevens, if anything, was being too polite.

IN 1957, as Congress was debating the first Civil Rights Act since Reconstruction, Buckley penned an op-ed that scrubbed away the euphemisms to get straight to the heart of the matter.

“Let us speak frankly,” Buckley wrote in the editorial, titled “Why The South Must Prevail.”

“The South does not want to deprive the Negro of a vote for the sake of depriving him of the vote,” he goes on. “In some parts of the South, the White community merely intends to prevail — that is all. It means to prevail on any issue on which there is corporate disagreement between Negro and White. The White community will take whatever measures are necessary to make certain that it has its way.”

Buckley goes on to weigh whether such a position is kosher from a sophisticated, conservative perspective. “The central question that emerges,” he writes, “is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas in which it does not predominate numerically?” His answer is clear:

The sobering answer is Yes — the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race. It is not easy, and it is unpleasant, to adduce statistics evidencing the median cultural superiority of White over Negro: but it is a fact that obtrudes, one that cannot be hidden by ever-so-busy egalitarians and anthropologists. The question, as far as the White community is concerned, is whether the claims of civilization supersede those of universal suffrage. The British believe they do, and acted accordingly, in Kenya, where the choice was dramatically one between civilization and barbarism, and elsewhere; the South, where the conflict is by no means dramatic, as in Kenya, nevertheless perceives important qualitative differences between its culture and the Negroes’, and intends to assert its own. NATIONAL REVIEW believes that the South’s premises are correct. If the majority wills what is socially atavistic, then to thwart the majority may be, though undemocratic, enlightened. It is more important for any community, anywhere in the world, to affirm and live by civilized standards, than to bow to the demands of the numerical majority.

Having justified denying the vote to Black people in the South as “enlightened,” Buckley then grapples with the proper level of violence needed to sustain the “civilized standards” he is intent on upholding.

Sometimes it becomes impossible to assert the will of a minority, in which case it must give way, and the society will regress; sometimes the numerical minority cannot prevail except by violence: then it must determine whether the prevalence of its will is worth the terrible price of violence.

By 1957, when Buckley was writing the column and Congress was considering its civil rights legislation, lynchings were continuing in the South, a mechanism of discipline to enforce Jim Crow, a regime that rendered the post-Civil War constitutional guarantees of the franchise and the right to equal protection of the laws mere words on paper. Buckley concluded the editorial by suggesting that with enough guidance and charity from white people in the South, Black people may one day be worthy of an equal standing.

Universal suffrage is not the beginning of wisdom or the beginning of freedom. Reasonable limitations upon the vote are not exclusively the recommendation of tyrants or oligarchists (was Jefferson either?). The problem in the South is not how to get the vote for the Negro, but how to equip the Negro—and a great many Whites—to cast an enlightened and responsible vote. The South confronts one grave moral challenge. It must not exploit the fact of Negro backwardness to preserve the Negro as a servile class. It is tempting and convenient to block the progress of a minority whose services, as menials, are economically useful. Let the South never permit itself to do this. So long as it is merely asserting the right to impose superior mores for whatever period it takes to effect a genuine cultural equality between the races, and so long as it does so by humane and charitable means, the South is in step with civilization, as is the Congress that permits it to function.

Disenfranchisement and a reasonable amount of violence were justified, Buckley wrote, to maintain society.

Buckley’s argument, “undemocratic” as it may be, is an articulate defense of white supremacy — with a capital W, as was the house style at the magazine then — as the proper means toward the goal of a good society. Maintaining that good society through disenfranchisement and a reasonable amount of violence was justified. The column appears not just in the magazine’s archives but also the 2008 book, “From The New Deal to The New Right: Race and the Southern Origins of Modern Conservatism,” published by Yale University Press and authored by Joseph E. Lowndes. The thesis of Lowndes’s book, that the fusion of Southern white supremacists and the business class was forged with the intellectual guidance of National Review, was buttressed by research a decade later: a paper from Cambridge University Press called, “‘Will the Jungle Take Over?’ National Review and the Defense of Western Civilization in the Era of Civil Rights and African Decolonization.”

Buckley made his argument in the context of an internal debate over the direction of the Republican Party as the New Deal realignment was reshaping politics. One wing of the party, dominated by the Rockefellers and other Northeastern politicians, argued for a multiracial, moderate, pro-business party that continued to compete across the country. The other wing — with Goldwater, Buckley, and the National Review as its lead champions — argued for an alliance between Southern segregationists gradually leaving the Democratic Party and pro-business forces around the country.

SCULLY PREFERS a vastly different history of this realignment. Goldwater, who served as an Arizona senator, ran for president in 1964: a failed campaign but one that is credited with birthing the modern Republican Party. In June of that year, he famously cast his vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, citing constitutional objections. Goldwater, Scully argues, was not involved in a “carefully crafted platform of coded racism,” but was simply a principled, small-government conservative:

To see what Goldwater’s “carefully crafted platform of coded racism” actually looked like, you have to go fetch it yourself. Republicans in 1964 pledged “full implementation and faithful execution of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and all other civil rights statutes; . . . such additional administrative or legislative actions as may be required to end the denial, for whatever unlawful reason, of the right to vote; . . . continued opposition to discrimination based on race, creed, national origin or sex. We recognize that the elimination of any such discrimination is a matter of heart, conscience, and education, as well as of equal rights under law.”

Across the South, we’re to believe, ears went up at the dog whistle in this language, so subtle that even now no one else can pick it up. Even if Stevens’s point is that 1964 marked a sharp decline in African-American votes for Republicans, that proves only that the sum of Goldwater’s platform and convictions held less appeal to black citizens than did Lyndon Johnson’s activist government and Great Society agenda. As NR’s Kevin Williamson has skillfully explained, African-American support for Democrats began to rise long before the 1960s with the programs of the New Deal. Everything isn’t about race; presumably black voters acted in the belief that these economic policies best served their own and their country’s interests. And this despite the fact that many prominent Democrats themselves in that era, including LBJ, had disgraceful records on civil rights.

On that score it would have been relevant for Stevens to mention that Barry Goldwater — the most upright of men, whose reputation was good enough for the proud one-time “Goldwater Girl” nominated for president in 2016 — was a champion of and fundraiser for efforts to end segregation in Phoenix schools, in 1946 led the desegregation of the Arizona National Guard, and was a founding member of the Arizona NAACP. Easy to fault the senator now for overthinking constitutional objections to elements of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, despite his consistent votes for civil-rights bills before that, and to note adverse electoral consequences for his party. But to accuse Republicans of stirring up racial hatred with that man and that platform is a gross misstatement of fact.

Ku Klux Klan members supporting Barry Goldwater’s campaign for the presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention in San Francisco, as an African American man pushes signs back, on July 12, 1964. Photo: Warren K Leffler/Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Most students of American political history are probably scratching their heads at how Scully could attempt to deny that Republicans exploited racial grievance to build its base of white voters in the South. Here, again, the real history of the National Review is instructive. Linking the business wing of the GOP with the racist wing of Democratic Party was not the easy task it seems in hindsight, but required decades of effort to help these disparate camps find their shared interests and fuse together.

Scully is right that Black Americans’ drift away from the GOP began long before the Civil Rights Act. A majority of Black voters went for virulent racist Woodrow Wilson in 1912, attracted by his progressive economic platform, the first time since winning the right to vote that Black voters had cast it for a Democrat for president. That trend continued over the next several decades. In 1948, Harry Truman insisted on including a strong civil rights plank in the party’s platform. Southerners walked out of the Democratic National Convention in protest and ran Strom Thurmond as their “Dixiecrat” nominee.

Voters, even white ones in the South, reacted to Thurmond with a yawn. He won 2.4 percent of the vote, just over a million, which was roughly what the Populist Party’s candidate had won in the 1890s. Truman won Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Texas, and the rest of the South and border states other than the four most hardcore: South Carolina, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. The Dixiecrat revolt was crushed.

or Northern Republicans to get behind segregation and the preservation of the white Southern way of life.

Getting each to accept the other was not inevitable, nor was it easy. That’s where th

It was clear that the South couldn’t win the fight alone, and for that, needed conservative allies in the North. The problem was that the rest of the country, Northern Republican conservatives included, wanted nothing to do with the explicit, raw racism on display in the South, preferring the more subtle kind that is more familiar today.

But those Republicans did want something else: an end to the New Deal. In order to forge the alliance between the racist Democrats in the South, then, and the business wing of the Republicans in the North, they had to fuse two, unlinked political movements — the drive for segregation and the rollback of the New Deal. That required the South to go along with attacking programs that were extremely popular with the people of the South, and fe National Review comes in.

The move was made by linking the New Deal to a big, overreaching government that, yes, had electrified the country, built Social Security, dug the country out of the Depression, and so on, but also wanted to forcibly integrate society and ensure the franchise for Black voters. Buckley was primarily against all the former insults upon the Constitution, and Southern segregationists were primarily against the latter. Buckley argued to Southerners that their defense of Jim Crow through the rhetoric of states’ rights was too often “opportunistic” rather than principled — inarguably true — and that if they didn’t embrace a broader ideology of limited government, they wouldn’t find the allies they needed to succeed.

With Southerners willing to break from the New Deal, the Northern Republican elites were open to some level of compromise on segregation that would allow white supremacy to continue without party leaders needing to endorse white supremacy. They satisfied their own consciences by pretending that their new allies weren’t racist; rather, they simply deeply believed in the principle of local democracy and states rights. That game of pretend is still going on in the National Review today.

THE MAGAZINE was founded in 1955 as a project to undermine the New Deal, with the famous motto, “It stands athwart history, yelling Stop.” It invested extraordinary amounts of time and resources into building an intellectual edifice for segregation that could be bandied about in polite society.

One 1956 editorial, titled “The South Girds Its Loins,” shows how it was typically done.

Ryan Grim July 5 2020,

STUART STEVENS, who has gone from running Mitt Romney’s campaign for president in 2012 to a perch as a leading Never Trumper, is out with a new book: his mea culpa of sorts, “It Was All a Lie: How the Republican Party Became Donald Trump.”

Some of Stevens’s former colleagues don’t like it, and one of them, Matthew Scully, savaged it in National Review. “Perhaps the most devastating book review you’ll ever read,” National Review editor Rich Lowry promised.

The review is, to be sure, unfriendly, countering that Stevens is, in so many words, a clown, a hack, a liar, a grifter — and wrong. I’m not here to referee the bulk of their dispute, but one particular claim by Scully in his review merits a closer look.

In his book, Stevens apologizes for his role in propping up a Republican Party he now considers to be little more than a “white grievance party” cynically exploiting racism in the pursuit of power. Scully objects to much of what Stevens has to say in the book, and he zeroes in on Stevens’s claim that, in hindsight, he should have seen all along that Republicans were getting ahead by exploiting racism. Stevens cites the rise of the New Right with Barry Goldwater’s campaign in 1964 straight through to President Donald Trump.

Scully is appalled at such libel upon the GOP, and comes to the spirited defense of Goldwater and one of his chief advocates, William F. Buckley Jr. Buckley was a founder of the National Review and, in many respects, the modern conservative movement, who, Stevens wrote, was simply “a more articulate version of the same deep ugliness and bigotry that is the hallmark of Trumpism.”

William F. Buckley, Stevens wrote, was simply “a more articulate version of the same deep ugliness and bigotry that is the hallmark of Trumpism.”

“As a rule of thumb,” Scully responds in the reportedly devastating review, “anyone so glib and presumptuous as to brush off as ‘ugliness and bigotry’ the enduring political and moral legacy of William F. Buckley Jr. has, for that reason alone, no business involving himself in Republican affairs.”

Scully might want to take a dive through the archives of his own magazine before offering such a definitive judgment. A review of that record shows there is no doubt which side of history Buckley placed himself on. Now, he stands athwart it with Trump, like it or not. Stevens, if anything, was being too polite.

IN 1957, as Congress was debating the first Civil Rights Act since Reconstruction, Buckley penned an op-ed that scrubbed away the euphemisms to get straight to the heart of the matter.

“Let us speak frankly,” Buckley wrote in the editorial, titled “Why The South Must Prevail.”

“The South does not want to deprive the Negro of a vote for the sake of depriving him of the vote,” he goes on. “In some parts of the South, the White community merely intends to prevail — that is all. It means to prevail on any issue on which there is corporate disagreement between Negro and White. The White community will take whatever measures are necessary to make certain that it has its way.”

Buckley goes on to weigh whether such a position is kosher from a sophisticated, conservative perspective. “The central question that emerges,” he writes, “is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas in which it does not predominate numerically?” His answer is clear:

The sobering answer is Yes — the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race. It is not easy, and it is unpleasant, to adduce statistics evidencing the median cultural superiority of White over Negro: but it is a fact that obtrudes, one that cannot be hidden by ever-so-busy egalitarians and anthropologists. The question, as far as the White community is concerned, is whether the claims of civilization supersede those of universal suffrage. The British believe they do, and acted accordingly, in Kenya, where the choice was dramatically one between civilization and barbarism, and elsewhere; the South, where the conflict is by no means dramatic, as in Kenya, nevertheless perceives important qualitative differences between its culture and the Negroes’, and intends to assert its own. NATIONAL REVIEW believes that the South’s premises are correct. If the majority wills what is socially atavistic, then to thwart the majority may be, though undemocratic, enlightened. It is more important for any community, anywhere in the world, to affirm and live by civilized standards, than to bow to the demands of the numerical majority.

Having justified denying the vote to Black people in the South as “enlightened,” Buckley then grapples with the proper level of violence needed to sustain the “civilized standards” he is intent on upholding.

Sometimes it becomes impossible to assert the will of a minority, in which case it must give way, and the society will regress; sometimes the numerical minority cannot prevail except by violence: then it must determine whether the prevalence of its will is worth the terrible price of violence.

By 1957, when Buckley was writing the column and Congress was considering its civil rights legislation, lynchings were continuing in the South, a mechanism of discipline to enforce Jim Crow, a regime that rendered the post-Civil War constitutional guarantees of the franchise and the right to equal protection of the laws mere words on paper. Buckley concluded the editorial by suggesting that with enough guidance and charity from white people in the South, Black people may one day be worthy of an equal standing.

Universal suffrage is not the beginning of wisdom or the beginning of freedom. Reasonable limitations upon the vote are not exclusively the recommendation of tyrants or oligarchists (was Jefferson either?). The problem in the South is not how to get the vote for the Negro, but how to equip the Negro—and a great many Whites—to cast an enlightened and responsible vote. The South confronts one grave moral challenge. It must not exploit the fact of Negro backwardness to preserve the Negro as a servile class. It is tempting and convenient to block the progress of a minority whose services, as menials, are economically useful. Let the South never permit itself to do this. So long as it is merely asserting the right to impose superior mores for whatever period it takes to effect a genuine cultural equality between the races, and so long as it does so by humane and charitable means, the South is in step with civilization, as is the Congress that permits it to function.

Disenfranchisement and a reasonable amount of violence were justified, Buckley wrote, to maintain society.

Buckley’s argument, “undemocratic” as it may be, is an articulate defense of white supremacy — with a capital W, as was the house style at the magazine then — as the proper means toward the goal of a good society. Maintaining that good society through disenfranchisement and a reasonable amount of violence was justified. The column appears not just in the magazine’s archives but also the 2008 book, “From The New Deal to The New Right: Race and the Southern Origins of Modern Conservatism,” published by Yale University Press and authored by Joseph E. Lowndes. The thesis of Lowndes’s book, that the fusion of Southern white supremacists and the business class was forged with the intellectual guidance of National Review, was buttressed by research a decade later: a paper from Cambridge University Press called, “‘Will the Jungle Take Over?’ National Review and the Defense of Western Civilization in the Era of Civil Rights and African Decolonization.”

Buckley made his argument in the context of an internal debate over the direction of the Republican Party as the New Deal realignment was reshaping politics. One wing of the party, dominated by the Rockefellers and other Northeastern politicians, argued for a multiracial, moderate, pro-business party that continued to compete across the country. The other wing — with Goldwater, Buckley, and the National Review as its lead champions — argued for an alliance between Southern segregationists gradually leaving the Democratic Party and pro-business forces around the country.

SCULLY PREFERS a vastly different history of this realignment. Goldwater, who served as an Arizona senator, ran for president in 1964: a failed campaign but one that is credited with birthing the modern Republican Party. In June of that year, he famously cast his vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, citing constitutional objections. Goldwater, Scully argues, was not involved in a “carefully crafted platform of coded racism,” but was simply a principled, small-government conservative:

To see what Goldwater’s “carefully crafted platform of coded racism” actually looked like, you have to go fetch it yourself. Republicans in 1964 pledged “full implementation and faithful execution of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and all other civil rights statutes; . . . such additional administrative or legislative actions as may be required to end the denial, for whatever unlawful reason, of the right to vote; . . . continued opposition to discrimination based on race, creed, national origin or sex. We recognize that the elimination of any such discrimination is a matter of heart, conscience, and education, as well as of equal rights under law.”

Across the South, we’re to believe, ears went up at the dog whistle in this language, so subtle that even now no one else can pick it up. Even if Stevens’s point is that 1964 marked a sharp decline in African-American votes for Republicans, that proves only that the sum of Goldwater’s platform and convictions held less appeal to black citizens than did Lyndon Johnson’s activist government and Great Society agenda. As NR’s Kevin Williamson has skillfully explained, African-American support for Democrats began to rise long before the 1960s with the programs of the New Deal. Everything isn’t about race; presumably black voters acted in the belief that these economic policies best served their own and their country’s interests. And this despite the fact that many prominent Democrats themselves in that era, including LBJ, had disgraceful records on civil rights.

On that score it would have been relevant for Stevens to mention that Barry Goldwater — the most upright of men, whose reputation was good enough for the proud one-time “Goldwater Girl” nominated for president in 2016 — was a champion of and fundraiser for efforts to end segregation in Phoenix schools, in 1946 led the desegregation of the Arizona National Guard, and was a founding member of the Arizona NAACP. Easy to fault the senator now for overthinking constitutional objections to elements of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, despite his consistent votes for civil-rights bills before that, and to note adverse electoral consequences for his party. But to accuse Republicans of stirring up racial hatred with that man and that platform is a gross misstatement of fact.

Ku Klux Klan members supporting Barry Goldwater’s campaign for the presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention in San Francisco, as an African American man pushes signs back, on July 12, 1964. Photo: Warren K Leffler/Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Most students of American political history are probably scratching their heads at how Scully could attempt to deny that Republicans exploited racial grievance to build its base of white voters in the South. Here, again, the real history of the National Review is instructive. Linking the business wing of the GOP with the racist wing of Democratic Party was not the easy task it seems in hindsight, but required decades of effort to help these disparate camps find their shared interests and fuse together.

Scully is right that Black Americans’ drift away from the GOP began long before the Civil Rights Act. A majority of Black voters went for virulent racist Woodrow Wilson in 1912, attracted by his progressive economic platform, the first time since winning the right to vote that Black voters had cast it for a Democrat for president. That trend continued over the next several decades. In 1948, Harry Truman insisted on including a strong civil rights plank in the party’s platform. Southerners walked out of the Democratic National Convention in protest and ran Strom Thurmond as their “Dixiecrat” nominee.

Voters, even white ones in the South, reacted to Thurmond with a yawn. He won 2.4 percent of the vote, just over a million, which was roughly what the Populist Party’s candidate had won in the 1890s. Truman won Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Texas, and the rest of the South and border states other than the four most hardcore: South Carolina, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. The Dixiecrat revolt was crushed.

or Northern Republicans to get behind segregation and the preservation of the white Southern way of life.

Getting each to accept the other was not inevitable, nor was it easy. That’s where th

It was clear that the South couldn’t win the fight alone, and for that, needed conservative allies in the North. The problem was that the rest of the country, Northern Republican conservatives included, wanted nothing to do with the explicit, raw racism on display in the South, preferring the more subtle kind that is more familiar today.

But those Republicans did want something else: an end to the New Deal. In order to forge the alliance between the racist Democrats in the South, then, and the business wing of the Republicans in the North, they had to fuse two, unlinked political movements — the drive for segregation and the rollback of the New Deal. That required the South to go along with attacking programs that were extremely popular with the people of the South, and fe National Review comes in.

The move was made by linking the New Deal to a big, overreaching government that, yes, had electrified the country, built Social Security, dug the country out of the Depression, and so on, but also wanted to forcibly integrate society and ensure the franchise for Black voters. Buckley was primarily against all the former insults upon the Constitution, and Southern segregationists were primarily against the latter. Buckley argued to Southerners that their defense of Jim Crow through the rhetoric of states’ rights was too often “opportunistic” rather than principled — inarguably true — and that if they didn’t embrace a broader ideology of limited government, they wouldn’t find the allies they needed to succeed.

With Southerners willing to break from the New Deal, the Northern Republican elites were open to some level of compromise on segregation that would allow white supremacy to continue without party leaders needing to endorse white supremacy. They satisfied their own consciences by pretending that their new allies weren’t racist; rather, they simply deeply believed in the principle of local democracy and states rights. That game of pretend is still going on in the National Review today.

THE MAGAZINE was founded in 1955 as a project to undermine the New Deal, with the famous motto, “It stands athwart history, yelling Stop.” It invested extraordinary amounts of time and resources into building an intellectual edifice for segregation that could be bandied about in polite society.

One 1956 editorial, titled “The South Girds Its Loins,” shows how it was typically done.

Those who oppose the South’s resistance tend to rest their case, simply, on the fact that they disapprove of racial discrimination of any kind. It has been surprisingly difficult to fix their attention on the fact that, as far as the South and its sympathies are concerned, something else is at stake. Indeed, support for the Southern position rests not at all on the question of whether Negro and White children should, in fact, study geography side by side; but on whether a central or local authority should make that decision.

National Review invested extraordinary amounts of time and resources into building an intellectual edifice for segregation that could be bandied about in polite society.

What makes the earlier passage from Buckley, explicitly justifying violence to perpetuate white dominance, so startling is not that the ideas in it are unusual or surprising, but that they are so nakedly on display. It was obvious to Buckley’s colleague and co-founder, L. Brent Bozell Jr., how damaging that messaging could be to the nascent efforts at an alliance between moderate, pro-business northern Republicans and segregationist Democrats. In the next issue, he pushed back.

“This magazine,” Bozell wrote, “has expressed views on the racial question that I consider dead wrong, and capable of doing grave hurt to the conservative movement.” Bozell argued that Buckley was making a mockery of the rule of law, undermining conservative values. Buckley responded with a “clarification” that the constitutional amendments that gave Black people the right to vote and the right to equal protection of the laws “are regarded by much of the South as inorganic accretions to the original document, grafted up int by a victor-at-war by force.” But he conceded to Bozell that conservatives should be more careful in how they frame their attacks on the right to vote by “enacting [voter suppression] laws that apply equally to blacks and whites.” Buckley was anticipating the color-blind logic Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts would use to gut the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

Bozell’s framing is what allows Scully to now claim that Goldwater was “the most upright of men,” without a racist bone in his body, and therefore the project itself could never have exploited racial grievance. We don’t need to see straight into the heart of Goldwater, though, to understand how the Republican Party really evolved.

James J. Kilpatrick, left, an editor of the Richmond, Va., News-Leader, appears with Martin Luther King Jr. before their debate on “Are Sit-In Strikes Justifiable?” which was televised Nov. 26, 1960, from NBC’s New York studios.

Photo: John Lent/AP

In 1962, regular National Review writer James Kilpatrick published a book called “The Southern Case for Segregation.” His case: “the Negro race, as a race, plainly is not equal to the white race, as a race; nor, for that matter, in the wider world beyond, by the accepted judgment of ten thousand years, has the Negro race, as a race, ever been the cultural or intellectual equal of the white race, as a race.”

The problem, he argued, was that Black leaders refuse to admit their own inferiority. “A really massive, significant change in race relations will not come until the Negro people develop leaders who will ask themselves the familiar question, ‘Why are we treated as second-class citizens?’ and return a candid answer to it: Because all too often that is what we are. … The Negro says he’s the white man’s equal; show me,” he wrote.

Kilpatrick and Buckley were close. Buckley assigned Kilpatrick to cover major segregation cases for the magazine, and once called him “the primary editorialist on our side of the fence. … In fact, I sometimes jocularly refer to him as ‘Number one,’” according to “The Fire is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate Over Race in America.”

In 1958, Kilpatrick connected Buckley with Bill Simmons, a leader of Citizens Council, an abjectly white supremacist organization, suggesting a partnership with National Review had potential. Simmons sent Buckley the organization’s mailing list, along with other offers of support. Buckley wrote back to thank him, in an anecdote relayed in “The Fire is Upon Us”: “I feel that our position on states’ rights is the same as your own and that we are therefore, as far as political decentralization is concerned, pursuing the same ends.” This was Buckley quite actively seeking an alliance with active and explicit white supremacists in order to fuse together his movement with theirs. Whatever he felt about them personally, his goal was to empower them.

Kilpatrick’s objectively white supremacist book was reviewed fondly in the pages of National Review by Bozell.

Bozell, who married Buckley’s sister (producing, among 10 children, conservative provocateur L. Brent Bozell III), would go on to ghostwrite Barry Goldwater’s defining 1960 book, “The Conscience of a Conservative,” and to serve as a top adviser to his 1964 presidential campaign — a campaign National Review helped make possible — refining the conservative language on race so that its meaning was easy to grasp but its words were slippery. “Bozell would help ensure that his would be the political course modern American conservatism would steer,” concluded Lowndes.

“I don’t like segregation,” Goldwater said in 1962. “But I don’t like the Constitution kicked around either.”

The language Bozell helped make famous was around local control. He used the concept of “interposition,” similar to “nullification,” which essentially said that a state, or group of states, was free to reject a federal law it found unconstitutional. Civil rights laws, considered unconstitutional in the South among white leaders, could therefore be ignored, and the states themselves could set the policy. Here, Goldwater would say that he personally felt that the Southern states ought to embrace civil rights, but that it was up to them. The result was the same as if he stridently opposed civil rights — and white Southern voters knew it, and flocked to Goldwater. “I don’t like segregation,” Goldwater said in 1962. “But I don’t like the Constitution kicked around either.”

The next year, National Review writer William Rusher, in an article called “Crossroads for the GOP,” argued that “Goldwater, and Goldwater alone, can carry enough Southern and Border States to offset the inevitable Kennedy conquests in the big industrial states of the North.” This could be done, Rusher suggested, without resorting to exploitation of racial grievance. But the same magazine issue, Lowndes found, included two cartoons, one of a bearded Confederate general holding aloft a GOP flag, and another of Confederate soldiers firing cannons, with the cannonballs labeled “Republican.” The cartoons are not reprinted in his book, though perhaps Scully or Lowry could dig them out of the archives. (Check the February 12, 1963 issue.)

After the ’64 convention — in which the civil rights plank, Scully neglects to mention, was watered down by removing the word “enforcement” — none other than Strom Thurmond rallied to Goldwater’s banner. He made a television announcement early in the fall that he was leaving the Democratic Party (again). “The Democratic Party,” he said, “has forsaken the people to become the party of minority groups, power-hungry union leaders, political bosses and big businessmen looking for government contracts and favors.” His indictment continued: The party “has rammed through Congress unconstitutional, unworkable and oppressive legislation which invades inalienable personal and property rights of the individual.”

He said that he’d be joining the “Goldwater Republican Party,” joining him in the fight “to make the Republican Party a party which supports freedom, justice and constitutional government.”

He was already a reader of the National Review, having been gifted a subscription by Buckley’s father who assured him that his son “is for segregation and backs it in every issue.”

Buckley, in a column in July 1963, warned that if Democrats tried to paint Goldwater’s movement as racist, it might “resignedly” just become that.

If the Democrats, in their anxiety to discredit Goldwater and the conservative wing of the Republican Party, hammer away at the themes that such sentiments as Goldwater’s add up to an anti-Negro policy, then those who side with Goldwater may begin reconstructing their habits of thought and argument; and eventual their policies. Thereafter, they might proceed, resignedly, on the assumption that what is anti-Negro and what is traditionally American are apparently the same thing. And that therefore one must now choose between staying free and trucking to the Negro vote.

That same year, conservative reporter Robert Novak attended an annual RNC meeting in Denver, concluding that “a good many, perhaps a majority of the party’s leaders, envisioned substantial political gold to be mined in the racial crisis by becoming in fact, though not in name, the White Man’s Party.”

William F. Buckley Jr. left, talks with former California Gov. Ronald Reagan at the South Carolina Governor’s Mansion in Columbia, S.C., on Jan. 13, 1978.

Photo: Lou Krasky/AP

Six years earlier, Buckley had made the forceful argument in the pages of National Review that “the White community is so entitled [to block Blacks from voting] because, for the time being, it is the advanced race.” Now Goldwater, with the enthusiastic support of Thurmond, was running on a platform that would legally allow such white supremacy to continue in the South. He lost badly to Lyndon B. Johnson, but Richard Nixon implemented the strategy in 1968, and the parties were realigned.

The GOP was now the White Man’s Party — courtesy of Goldwater, Buckley, and National Review.

The tragedy of Buckley is that he did personally evolve on questions of Jim Crow. The civil rights movement and the white violence that met it did help Buckley genuinely evolve. He came around to support federal enforcement of civil rights laws, the rights of Black people to vote, and even affirmative action to right years of injustice. He attacked the John Birch Society and warred with anti-Semites. When Kilpatrick eventually gave up defending segregation, Buckley cheered him.

But like so many too-clever operatives before him and since, the forces he empowered became too powerful for him and his magazine. Buckley may have thought he was exploiting the Citizens Council for his own movement’s gain, but it worked the other way around.

Today, it’s unfolding as farce. In January 2016, National Review dedicated an entire issue to taking down Trump, making a full-throated conservative case against him.

One of the columns is drafted by Bozell’s son, L. Brent Bozell III. “Trump might be the greatest charlatan of them all,” Bozell III suggested, comparing him unfavorably to Ronald Reagan, who, Bozell III noted, was a devoted reader of National Review and “supported Barry Goldwater when the GOP mainstream turned its back on him.”

National Review has since been brought around, and is four-square behind Trump. He has the right instincts and enemies, the magazine argues, even if his language could use some greater sophistication. But now that Buckley’s ghost has bent the knee to the Citizens’ Council, nobody in Trump’s world cares what National Review thinks. The magazine’s faux-intellectual discourse is no longer needed by the forces that Buckley — resignedly or not — built up. All that’s left to do for the magazine is hug closer to Trump, and celebrate each new lifetime judicial confirmation. After all, there may be some differences, but, in the words of Buckley, both partners are “pursuing the same ends.” What could go wrong?

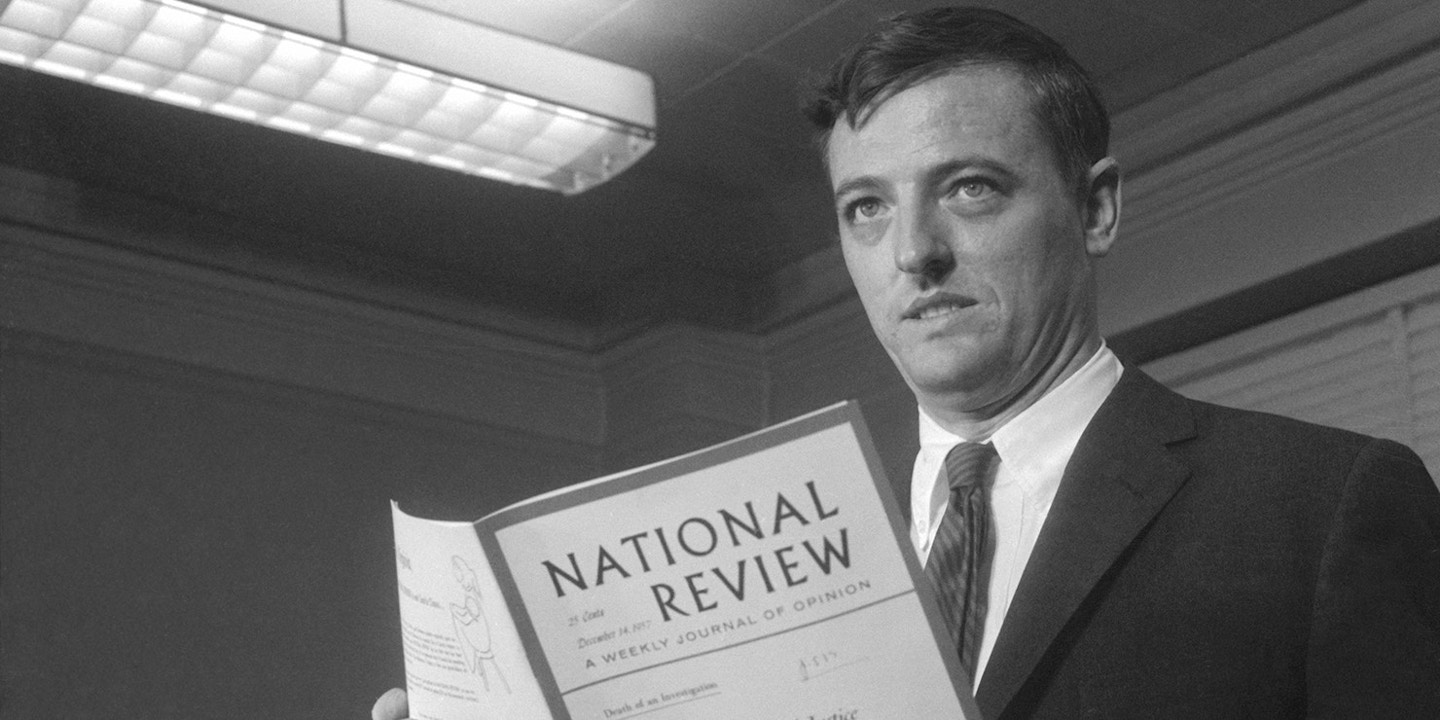

TOP PHOTO Magazine editor William F. Buckley Jr., editor of the National Review, holds a copy of the magazine as he makes a statement on the steps of the U.S. Courthouse on May 13, 1958. Bettmann Archive

National Review invested extraordinary amounts of time and resources into building an intellectual edifice for segregation that could be bandied about in polite society.

What makes the earlier passage from Buckley, explicitly justifying violence to perpetuate white dominance, so startling is not that the ideas in it are unusual or surprising, but that they are so nakedly on display. It was obvious to Buckley’s colleague and co-founder, L. Brent Bozell Jr., how damaging that messaging could be to the nascent efforts at an alliance between moderate, pro-business northern Republicans and segregationist Democrats. In the next issue, he pushed back.

“This magazine,” Bozell wrote, “has expressed views on the racial question that I consider dead wrong, and capable of doing grave hurt to the conservative movement.” Bozell argued that Buckley was making a mockery of the rule of law, undermining conservative values. Buckley responded with a “clarification” that the constitutional amendments that gave Black people the right to vote and the right to equal protection of the laws “are regarded by much of the South as inorganic accretions to the original document, grafted up int by a victor-at-war by force.” But he conceded to Bozell that conservatives should be more careful in how they frame their attacks on the right to vote by “enacting [voter suppression] laws that apply equally to blacks and whites.” Buckley was anticipating the color-blind logic Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts would use to gut the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

Bozell’s framing is what allows Scully to now claim that Goldwater was “the most upright of men,” without a racist bone in his body, and therefore the project itself could never have exploited racial grievance. We don’t need to see straight into the heart of Goldwater, though, to understand how the Republican Party really evolved.

James J. Kilpatrick, left, an editor of the Richmond, Va., News-Leader, appears with Martin Luther King Jr. before their debate on “Are Sit-In Strikes Justifiable?” which was televised Nov. 26, 1960, from NBC’s New York studios.

Photo: John Lent/AP

In 1962, regular National Review writer James Kilpatrick published a book called “The Southern Case for Segregation.” His case: “the Negro race, as a race, plainly is not equal to the white race, as a race; nor, for that matter, in the wider world beyond, by the accepted judgment of ten thousand years, has the Negro race, as a race, ever been the cultural or intellectual equal of the white race, as a race.”

The problem, he argued, was that Black leaders refuse to admit their own inferiority. “A really massive, significant change in race relations will not come until the Negro people develop leaders who will ask themselves the familiar question, ‘Why are we treated as second-class citizens?’ and return a candid answer to it: Because all too often that is what we are. … The Negro says he’s the white man’s equal; show me,” he wrote.

Kilpatrick and Buckley were close. Buckley assigned Kilpatrick to cover major segregation cases for the magazine, and once called him “the primary editorialist on our side of the fence. … In fact, I sometimes jocularly refer to him as ‘Number one,’” according to “The Fire is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate Over Race in America.”

In 1958, Kilpatrick connected Buckley with Bill Simmons, a leader of Citizens Council, an abjectly white supremacist organization, suggesting a partnership with National Review had potential. Simmons sent Buckley the organization’s mailing list, along with other offers of support. Buckley wrote back to thank him, in an anecdote relayed in “The Fire is Upon Us”: “I feel that our position on states’ rights is the same as your own and that we are therefore, as far as political decentralization is concerned, pursuing the same ends.” This was Buckley quite actively seeking an alliance with active and explicit white supremacists in order to fuse together his movement with theirs. Whatever he felt about them personally, his goal was to empower them.

Kilpatrick’s objectively white supremacist book was reviewed fondly in the pages of National Review by Bozell.

Bozell, who married Buckley’s sister (producing, among 10 children, conservative provocateur L. Brent Bozell III), would go on to ghostwrite Barry Goldwater’s defining 1960 book, “The Conscience of a Conservative,” and to serve as a top adviser to his 1964 presidential campaign — a campaign National Review helped make possible — refining the conservative language on race so that its meaning was easy to grasp but its words were slippery. “Bozell would help ensure that his would be the political course modern American conservatism would steer,” concluded Lowndes.

“I don’t like segregation,” Goldwater said in 1962. “But I don’t like the Constitution kicked around either.”

The language Bozell helped make famous was around local control. He used the concept of “interposition,” similar to “nullification,” which essentially said that a state, or group of states, was free to reject a federal law it found unconstitutional. Civil rights laws, considered unconstitutional in the South among white leaders, could therefore be ignored, and the states themselves could set the policy. Here, Goldwater would say that he personally felt that the Southern states ought to embrace civil rights, but that it was up to them. The result was the same as if he stridently opposed civil rights — and white Southern voters knew it, and flocked to Goldwater. “I don’t like segregation,” Goldwater said in 1962. “But I don’t like the Constitution kicked around either.”

The next year, National Review writer William Rusher, in an article called “Crossroads for the GOP,” argued that “Goldwater, and Goldwater alone, can carry enough Southern and Border States to offset the inevitable Kennedy conquests in the big industrial states of the North.” This could be done, Rusher suggested, without resorting to exploitation of racial grievance. But the same magazine issue, Lowndes found, included two cartoons, one of a bearded Confederate general holding aloft a GOP flag, and another of Confederate soldiers firing cannons, with the cannonballs labeled “Republican.” The cartoons are not reprinted in his book, though perhaps Scully or Lowry could dig them out of the archives. (Check the February 12, 1963 issue.)

After the ’64 convention — in which the civil rights plank, Scully neglects to mention, was watered down by removing the word “enforcement” — none other than Strom Thurmond rallied to Goldwater’s banner. He made a television announcement early in the fall that he was leaving the Democratic Party (again). “The Democratic Party,” he said, “has forsaken the people to become the party of minority groups, power-hungry union leaders, political bosses and big businessmen looking for government contracts and favors.” His indictment continued: The party “has rammed through Congress unconstitutional, unworkable and oppressive legislation which invades inalienable personal and property rights of the individual.”

He said that he’d be joining the “Goldwater Republican Party,” joining him in the fight “to make the Republican Party a party which supports freedom, justice and constitutional government.”

He was already a reader of the National Review, having been gifted a subscription by Buckley’s father who assured him that his son “is for segregation and backs it in every issue.”

Buckley, in a column in July 1963, warned that if Democrats tried to paint Goldwater’s movement as racist, it might “resignedly” just become that.

If the Democrats, in their anxiety to discredit Goldwater and the conservative wing of the Republican Party, hammer away at the themes that such sentiments as Goldwater’s add up to an anti-Negro policy, then those who side with Goldwater may begin reconstructing their habits of thought and argument; and eventual their policies. Thereafter, they might proceed, resignedly, on the assumption that what is anti-Negro and what is traditionally American are apparently the same thing. And that therefore one must now choose between staying free and trucking to the Negro vote.

That same year, conservative reporter Robert Novak attended an annual RNC meeting in Denver, concluding that “a good many, perhaps a majority of the party’s leaders, envisioned substantial political gold to be mined in the racial crisis by becoming in fact, though not in name, the White Man’s Party.”

William F. Buckley Jr. left, talks with former California Gov. Ronald Reagan at the South Carolina Governor’s Mansion in Columbia, S.C., on Jan. 13, 1978.

Photo: Lou Krasky/AP

Six years earlier, Buckley had made the forceful argument in the pages of National Review that “the White community is so entitled [to block Blacks from voting] because, for the time being, it is the advanced race.” Now Goldwater, with the enthusiastic support of Thurmond, was running on a platform that would legally allow such white supremacy to continue in the South. He lost badly to Lyndon B. Johnson, but Richard Nixon implemented the strategy in 1968, and the parties were realigned.

The GOP was now the White Man’s Party — courtesy of Goldwater, Buckley, and National Review.

The tragedy of Buckley is that he did personally evolve on questions of Jim Crow. The civil rights movement and the white violence that met it did help Buckley genuinely evolve. He came around to support federal enforcement of civil rights laws, the rights of Black people to vote, and even affirmative action to right years of injustice. He attacked the John Birch Society and warred with anti-Semites. When Kilpatrick eventually gave up defending segregation, Buckley cheered him.

But like so many too-clever operatives before him and since, the forces he empowered became too powerful for him and his magazine. Buckley may have thought he was exploiting the Citizens Council for his own movement’s gain, but it worked the other way around.

Today, it’s unfolding as farce. In January 2016, National Review dedicated an entire issue to taking down Trump, making a full-throated conservative case against him.

One of the columns is drafted by Bozell’s son, L. Brent Bozell III. “Trump might be the greatest charlatan of them all,” Bozell III suggested, comparing him unfavorably to Ronald Reagan, who, Bozell III noted, was a devoted reader of National Review and “supported Barry Goldwater when the GOP mainstream turned its back on him.”

National Review has since been brought around, and is four-square behind Trump. He has the right instincts and enemies, the magazine argues, even if his language could use some greater sophistication. But now that Buckley’s ghost has bent the knee to the Citizens’ Council, nobody in Trump’s world cares what National Review thinks. The magazine’s faux-intellectual discourse is no longer needed by the forces that Buckley — resignedly or not — built up. All that’s left to do for the magazine is hug closer to Trump, and celebrate each new lifetime judicial confirmation. After all, there may be some differences, but, in the words of Buckley, both partners are “pursuing the same ends.” What could go wrong?

TOP PHOTO Magazine editor William F. Buckley Jr., editor of the National Review, holds a copy of the magazine as he makes a statement on the steps of the U.S. Courthouse on May 13, 1958. Bettmann Archive