Researchers find that the benefits of inhalers for asthma sufferers outweigh the risks of contracting coronavirus, following concerns raised after WHO warned that steroids could reduce immunity.

Date:July 9, 2020 Source:University of Huddersfield

The benefits of using inhalers and nebulisers containing steroids outweigh the risks despite warnings to the contrary during the COVID-19 pandemic, a study by University of Huddersfield researchers has found.

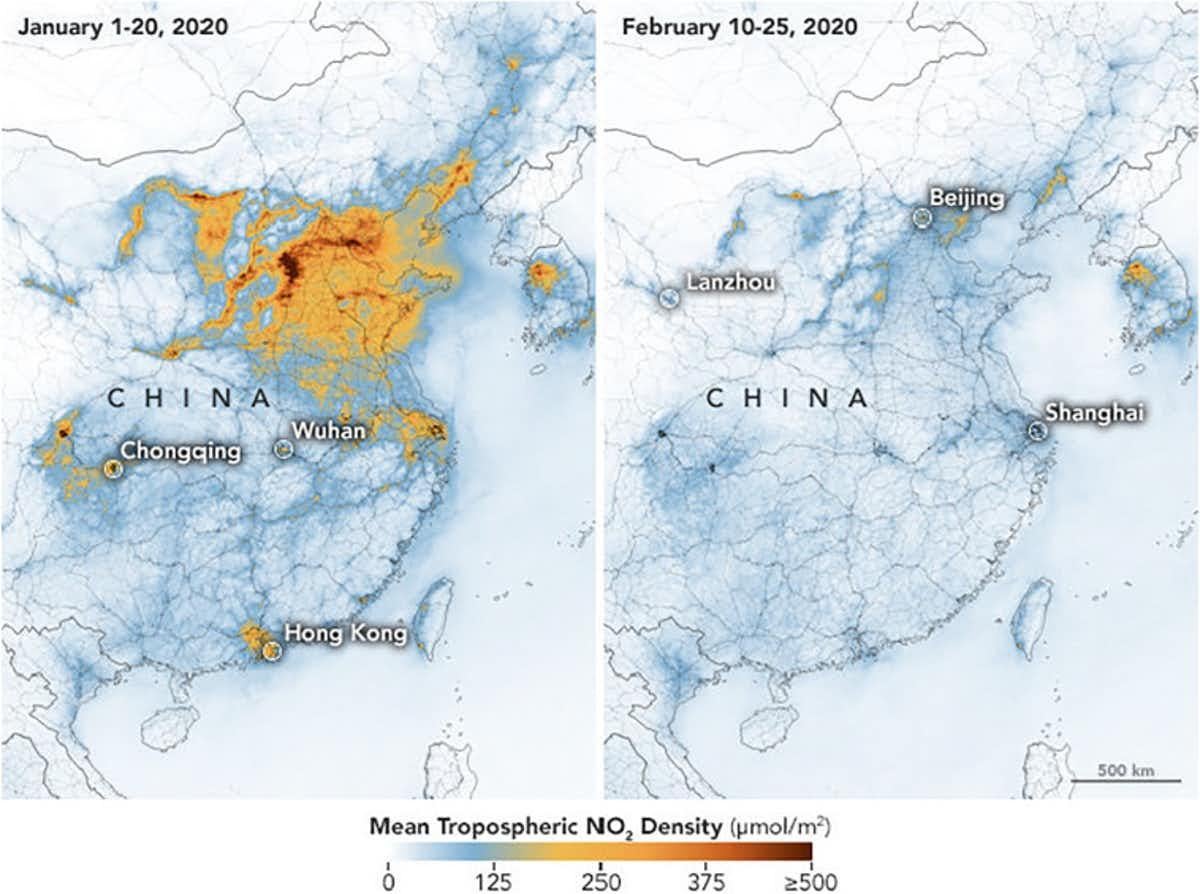

A warning issued by WHO in March advised that steroids used in inhalers and nebulisers could have a negative effect on a user's immunity system, leaving them more susceptible to COVID-19. The concern was that regular steroid use could leave users vulnerable to contracting the virus, or developing a more severe version than non-users.

WHO's cautionary note caused worry for people with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), leaving them unsure about whether they could keep using inhalers and nebulisers or not. The British Thoracic Society had reported that demand for inhalers had jumped by 400%, leading to shortages in the UK, following WHO's announcement.

However, Dr Hamid Merchant and Dr Syed Shahzad Hasan from the University of Huddersfield commissioned research into the use of steroids and risk of infections, especially viral infections of the upper respiratory tract. That included previous outbreaks of SARS, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic.

"It confused a lot of people," says Dr Hasan. "After the WHO advice, people thought that continuous use of steroids would leave them at a greater risk of contracting the virus or developing more than a mild version of CoViD-19."

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and oral corticosteroids (OCS) are prescribed to help asthma sufferers and those with COPD, with inhalers used to prevent attacks.

The study has been published in Respiratory Medicine, having assessed evidence and findings from a range of bodies including the British Thoracic Society and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The other authors in the study included Toby Capstick (a consultant pharmacist on respiratory medicine at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust), Syed Tabish Zaidi (Associate Professor in Pharmacy at the University of Leeds) and Chia Siang Kow (a clinical pharmacist from Malaysia).

"We found there is strong evidence that the benefits of continuing with steroids outweighs the risk," declares Dr Merchant.

"There is a risk that the immune system goes down, and there is a chance of acquiring infections but the benefits of continuing with steroids throughout were higher than the risks. We concluded by saying that the patients should continue their regular medicines including steroids."

Journal Reference:

Syed Shahzad Hasan, Toby Capstick, Syed Tabish Razi Zaidi, Chia Siang Kow, Hamid A. Merchant. Use of corticosteroids in asthma and COPD patients with or without COVID-19. Respiratory Medicine, 2020; 170: 106045 DOI: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106045

A warning issued by WHO in March advised that steroids used in inhalers and nebulisers could have a negative effect on a user's immunity system, leaving them more susceptible to COVID-19. The concern was that regular steroid use could leave users vulnerable to contracting the virus, or developing a more severe version than non-users.

WHO's cautionary note caused worry for people with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), leaving them unsure about whether they could keep using inhalers and nebulisers or not. The British Thoracic Society had reported that demand for inhalers had jumped by 400%, leading to shortages in the UK, following WHO's announcement.

However, Dr Hamid Merchant and Dr Syed Shahzad Hasan from the University of Huddersfield commissioned research into the use of steroids and risk of infections, especially viral infections of the upper respiratory tract. That included previous outbreaks of SARS, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic.

"It confused a lot of people," says Dr Hasan. "After the WHO advice, people thought that continuous use of steroids would leave them at a greater risk of contracting the virus or developing more than a mild version of CoViD-19."

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and oral corticosteroids (OCS) are prescribed to help asthma sufferers and those with COPD, with inhalers used to prevent attacks.

The study has been published in Respiratory Medicine, having assessed evidence and findings from a range of bodies including the British Thoracic Society and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The other authors in the study included Toby Capstick (a consultant pharmacist on respiratory medicine at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust), Syed Tabish Zaidi (Associate Professor in Pharmacy at the University of Leeds) and Chia Siang Kow (a clinical pharmacist from Malaysia).

"We found there is strong evidence that the benefits of continuing with steroids outweighs the risk," declares Dr Merchant.

"There is a risk that the immune system goes down, and there is a chance of acquiring infections but the benefits of continuing with steroids throughout were higher than the risks. We concluded by saying that the patients should continue their regular medicines including steroids."

Journal Reference:

Syed Shahzad Hasan, Toby Capstick, Syed Tabish Razi Zaidi, Chia Siang Kow, Hamid A. Merchant. Use of corticosteroids in asthma and COPD patients with or without COVID-19. Respiratory Medicine, 2020; 170: 106045 DOI: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106045