The Supreme Court of the United States has barely had time to gather its collective breath this last few days. Among its decisions, including those dealing with President Donald Trump’s financial records, was that of McGirt v Oklahoma. The case furnishes a detailed discussion on the extent Native American self-governance survived the assaults of the US Congress and the creation of the State of Oklahoma in 1907.

The Creek (Muscogee) Reservation itself arose from circumstances of predation and cruelty. Forcibly relocated from Georgia and Alabama, “the Creek nation,” wrote Justice Neil Gorsuch, “received reassurances that their new lands in the West would be secure forever. In ceding their land East of the Mississippi River, a pledge by the 1832 treaty was made that the “Creek country west of the Mississippi shall be solemnly guaranteed to the Creek Indians.”

By the narrowest of decisions, the court found 5-4 against the state of Oklahoma. The state authorities had claimed that the Creek Reservation did not survive the “allotment era” and had been “disestablished”. Jimcy McGirt, convicted by an Oklahoman state court of three sexual offences that had taken place on the Creek Nation Reservation in the north-eastern part of the state, had claimed otherwise. As a member of the Seminole Nation, he submitted in post-conviction proceedings that the State lacked jurisdiction to prosecute him. The relevant statute was the federal Major Crimes Act, which provided that, within “the Indian country”, any Indian committing certain offences “shall be subject to the same law and penalties as all other persons committing any of [those] offenses, within the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States”. His initial effort to seek a new trial in federal court failed, leading to the Supreme Court petition.

That period of central government nastiness in the late nineteenth century known as the “allotment era” had a purpose common to other frontier societies: the assimilation of the native intransigents through means designed to wean them off their traditional customs. As the zealous Captain Richard Pratt opined in 1892, the United States needed to “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Enough with the physical massacres; what was needed was a concerted effort to Americanize and civilise, a form of spiritual genocide. Pratt envisaged doing so through education, including the US Training and Industrial School he founded in 1879 at Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. Out with the “savage” habits: tribal language, identity and long hair; in with the new American, albeit a stunted one with his nerves extracted. Such education was to be rudimentary or, in the words of President Teddy Roosevelt, “very, very limited.”

In terms of property, the allotment era was trumpeted by the passage of the Dawes Act of 1887, also known as the General Allotment Act. This entailed breaking up tribally owned reservations and allocating them to individual households, though the process came with a nasty catch: such divided land would initially be held in trust; Native American households would have to prove their competence in exercising full “fee simple” property rights. The result, in many instances, was also the selling of Indian land to non-Indian purchasers.

In his address to Congress in 1901, Roosevelt gave his boisterous assessment of the statute. “The General Allotment Act is a mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass. It acts directly upon the family and the individual.” The Act had enabled sixty thousand Indians to become US citizens. It was now essential, Roosevelt suggested, to “break up the tribal funds, doing for them what allotment does for tribal lands; that is, they should be divided into individual holdings.”

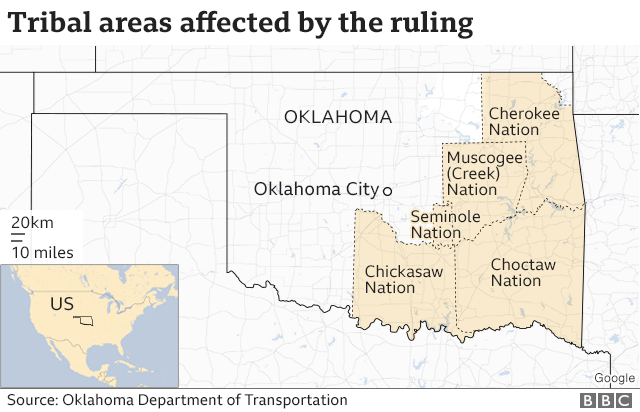

The majority, ruling in favour of McGirt, affirmed that the land in question remains a reservation that gives the federal government exclusive jurisdiction over crimes committed on it. In doing so, the court also confirmed the continuing existence of a reservation stretching some 19 million acres including eight counties and most of Tulsa.

In their skirt through the legislative record, the majority found no statute “evincing anything like the ‘present and total surrender of all tribal interests’.” The transfer of individual plots, whether to Native Americans or others, “did not disestablish the reservation”. A body of statutes and treaties over time confirmed the legal standing of the Creek Reservation. The majority rebuked the argument that States had claimed powers “to reduce federal reservations within their borders”. To imagine such a power would enable States to “encroach on the tribal boundaries or legal rights Congress provided, and, with enough time and patience, nullify the promises made in the name of the United States.” Despite various efforts by Congress to intrude upon Creek self-governance, these were not sufficient to suggest disestablishment. “Oklahoma and the dissent have cited no case in which this Court has found a reservation disestablished without first concluding that a statute first required that result.”

Chief Justice John Roberts, who managed to avoid being in the majority in all 5-4 court decisions this term, was glum about the consequences. The decision was a torch taken to state governance. “Across the vast area, the State’s ability to prosecute serious crimes will be hobbled and decades of past convictions could well be thrown out. On top of that, the Court has profoundly destabilized the governance of eastern Oklahoma.” The majority judgement had also created “significant uncertainty for the State’s continuing authority over any area that touches Indian affairs, ranging from zoning and taxation to family and environmental law.”

Roberts further bristled at the idea that Congress needed to be wordily explicit in terminating a reservation, having “made abundantly clear its intent to disestablish the Creek territory”. Just look at the historical record, the chief justice urged. Congress “supplanted the Creek legal system with a legal code and court system that applied equally to Indians and non-Indians.” It “systematically dismantled the governmental authority of the Creek Nation, targeting all three branches.” It “destroyed the foundation of sovereignty by stripping the Creek Nation of its territory.”

Justice Gorsuch, in his judgment for the majority, had little time for such worries. To suggest an army of inmates rushing to seek new trials in federal courts was “admittedly speculative, because many defendants may choose to finish their state sentences rather than risk prosecution in federal court where sentences can be graver”. Besides, no actual intention to terminate the legal standing of the Creek Reservation could ever be found.

In all the excitement, it would have been easy to have overlooked the predecessor case of Sharp v Murphy, in which the court heard argument on the same question as that of McGirt. The case stalled in its tracks in 2018 as Gorsuch had recused himself, having served on the 10th circuit of the US Circuit Court of Appeals, comprising Oklahoma. Instead of going through re-arguments there, Sharp was restored to this calendar term and duly decided in favour of the inmate Patrick Murphy “for the reasons stated in” McGirt. Murphy had also committed his crime within the boundaries of the Creek Nation.

Having anticipated the decision, somewhat, Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter, along with all Five Tribes affected by the decision, including the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole Nations, issued a statement committing the parties “to ensuring that Jimcy McGirt, Patrick Murphy, and all other offenders face justice for crimes for which they are accused. We have a shared commitment to maintaining public safety and long-term economic prosperity for the Nations and Oklahoma.”

The decision of McGirt masks the crude realities of institutional, colonial violence. It perpetuates an illusion, a discredited understanding between Native American nations and the US federal government. That was the lingering “promise”, as Gorsuch claims, “[o]n the far end of the Trail of Tears”, one that was never kept. Chief Justice Roberts was very much on to it. In letting the cat out of the bag on Native American-Indian relations, he suggested that Congress had acted in a manner entirely inconsistent with preserving any semblance of Creek sovereignty. We are left with the Native American Indian in confused legal dress, trampled, abused, deceived by history but with only a symbolic heartbeat.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com

Democratic Anarchy will Build the Best Life Possible

Why on Earth a Country of Laws and Borders?

Reconciling Mutual Aid With Revolutionary Violence: The Case of Peter Kropotkin

Human Potential: The Case of Peter Kropotkin

Propaganda By Deed And The Glory Of Self-Sacrifice: The Case of Peter Kropotkin