The Invention of the Police

Why did American policing get so big, so fast? The answer, mainly, is slavery.

By Jill Lepore July 13, 2020 THE NEW YORKER

The Chinatown Squad, a notoriously harsh police unit in San Francisco, in 1905.

Photograph courtesy Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

To police is to maintain law and order, but the word derives from polis—the Greek for “city,” or “polity”—by way of politia, the Latin for “citizenship,” and it entered English from the Middle French police, which meant not constables but government. “The police,” as a civil force charged with deterring crime, came to the United States from England and is generally associated with monarchy—“keeping the king’s peace”—which makes it surprising that, in the antimonarchical United States, it got so big, so fast. The reason is, mainly, slavery.

“Abolish the police,” as a rallying cry, dates to 1988 (the year that N.W.A. recorded “Fuck tha Police”), but, long before anyone called for its abolition, someone had to invent the police: the ancient Greek polis had to become the modern police. “To be political, to live in a polis, meant that everything was decided through words and persuasion and not through force and violence,” Hannah Arendt wrote in “The Human Condition.” In the polis, men argued and debated, as equals, under a rule of law. Outside the polis, in households, men dominated women, children, servants, and slaves, under a rule of force. This division of government sailed down the river of time like a raft, getting battered, but also bigger, collecting sticks and mud. Kings asserted a rule of force over their subjects on the idea that their kingdom was their household. In 1769, William Blackstone, in his “Commentaries on the Laws of England,” argued that the king, as “pater-familias of the nation,” directs “the public police,” exercising the means by which “the individuals of the state, like members of a well-governed family, are bound to conform their general behavior to the rules of propriety, good neighbourhood, and good manners; and to be decent, industrious, and inoffensive in their respective stations.” The police are the king’s men.

History begins with etymology, but it doesn’t end there. The polis is not the police. The American Revolution toppled the power of the king over his people—in America, “the law is king,” Thomas Paine wrote—but not the power of a man over his family. The power of the police has its origins in that kind of power. Under the rule of law, people are equals; under the rule of police, as the legal theorist Markus Dubber has written, we are not. We are more like the women, children, servants, and slaves in a household in ancient Greece, the people who were not allowed to be a part of the polis. But for centuries, through struggles for independence, emancipation, enfranchisement, and equal rights, we’ve been fighting to enter the polis. One way to think about “Abolish the police,” then, is as an argument that, now that all of us have finally clawed our way into the polis, the police are obsolete.

But are they? The crisis in policing is the culmination of a thousand other failures—failures of education, social services, public health, gun regulation, criminal justice, and economic development. Police have a lot in common with firefighters, E.M.T.s, and paramedics: they’re there to help, often at great sacrifice, and by placing themselves in harm’s way. To say that this doesn’t always work out, however, does not begin to cover the size of the problem. The killing of George Floyd, in Minneapolis, cannot be wished away as an outlier. In each of the past five years, police in the United States have killed roughly a thousand people. (During each of those same years, about a hundred police officers were killed in the line of duty.) One study suggests that two-thirds of Americans between the ages of fifteen and thirty-four who were treated in emergency rooms suffered from injuries inflicted by police and security guards, about as many people as the number of pedestrians injured by motor vehicles. Urban police forces are nearly always whiter than the communities they patrol. The victims of police brutality are disproportionately Black teen-age boys: children. To say that many good and admirable people are police officers, dedicated and brave public servants, which is, of course, true, is to fail to address both the nature and the scale of the crisis and the legacy of centuries of racial injustice. The best people, with the best of intentions, doing their utmost, cannot fix this system from within.

There are nearly seven hundred thousand police officers in the United States, about two for every thousand people, a rate that is lower than the European average. The difference is guns. Police in Finland fired six bullets in all of 2013; in an encounter on a single day in the year 2015, in Pasco, Washington, three policemen fired seventeen bullets when they shot and killed an unarmed thirty-five-year-old orchard worker from Mexico. Five years ago, when the Guardian counted police killings, it reported that, “in the first 24 days of 2015, police in the US fatally shot more people than police did in England and Wales, combined, over the past 24 years.” American police are armed to the teeth, with more than seven billion dollars’ worth of surplus military equipment off-loaded by the Pentagon to eight thousand law-enforcement agencies since 1997. At the same time, they face the most heavily armed civilian population in the world: one in three Americans owns a gun, typically more than one. Gun violence undermines civilian life and debases everyone. A study found that, given the ravages of stress, white male police officers in Buffalo have a life expectancy twenty-two years shorter than that of the average American male. The debate about policing also has to do with all the money that’s spent paying heavily armed agents of the state to do things that they aren’t trained to do and that other institutions would do better. History haunts this debate like a bullet-riddled ghost.

That history begins in England, in the thirteenth century, when maintaining the king’s peace became the duty of an officer of the court called a constable, aided by his watchmen: every male adult could be called on to take a turn walking a ward at night and, if trouble came, to raise a hue and cry. This practice lasted for centuries. (A version endures: George Zimmerman, when he shot and killed Trayvon Martin, in 2012, was serving on his neighborhood watch.) The watch didn’t work especially well in England—“The average constable is an ignoramus who knows little or nothing of the law,” Blackstone wrote—and it didn’t work especially well in England’s colonies. Rich men paid poor men to take their turns on the watch, which meant that most watchmen were either very elderly or very poor, and very exhausted from working all day. Boston established a watch in 1631. New York tried paying watchmen in 1658. In Philadelphia, in 1705, the governor expressed the view that the militia could make the city safer than the watch, but militias weren’t supposed to police the king’s subjects; they were supposed to serve the common defense—waging wars against the French, fighting Native peoples who were trying to hold on to their lands, or suppressing slave rebellions.

The government of slavery was not a rule of law. It was a rule of police. In 1661, the English colony of Barbados passed its first slave law; revised in 1688, it decreed that “Negroes and other Slaves” were “wholly unqualified to be governed by the Laws . . . of our Nations,” and devised, instead, a special set of rules “for the good Regulating and Ordering of them.” Virginia adopted similar measures, known as slave codes, in 1680:

It shall not be lawfull for any negroe or other slave to carry or arme himselfe with any club, staffe, gunn, sword or any other weapon of defence or offence, nor to goe or depart from of his masters ground without a certificate from his master, mistris or overseer, and such permission not to be granted but upon perticuler and necessary occasions; and every negroe or slave soe offending not haveing a certificate as aforesaid shalbe sent to the next constable, who is hereby enjoyned and required to give the said negroe twenty lashes on his bare back well layd on, and soe sent home to his said master, mistris or overseer . . . that if any negroe or other slave shall absent himself from his masters service and lye hid and lurking in obscure places, comitting injuries to the inhabitants, and shall resist any person or persons that shalby any lawfull authority be imployed to apprehend and take the said negroe, that then in case of such resistance, it shalbe lawfull for such person or persons to kill the said negroe or slave soe lying out and resisting.

In eighteenth-century New York, a person held as a slave could not gather in a group of more than three; could not ride a horse; could not hold a funeral at night; could not be out an hour after sunset without a lantern; and could not sell “Indian corn, peaches, or any other fruit” in any street or market in the city. Stop and frisk, stop and whip, shoot to kill.

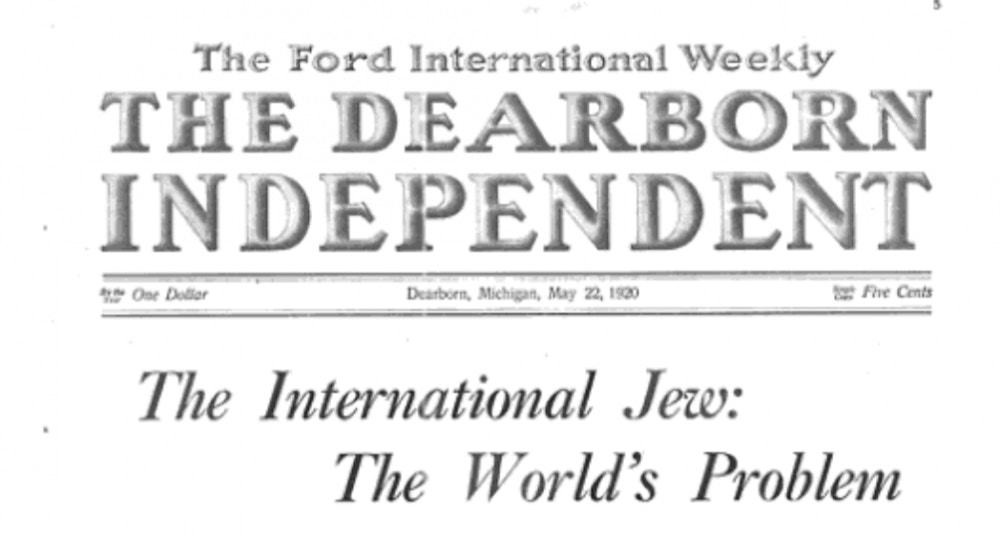

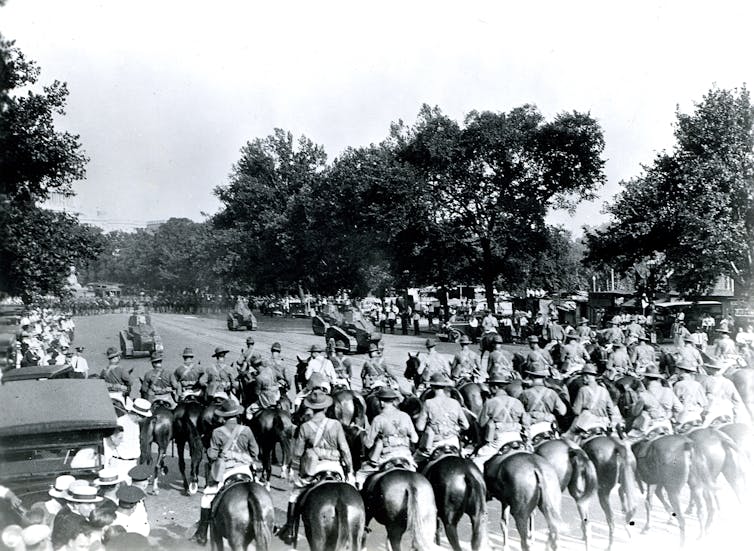

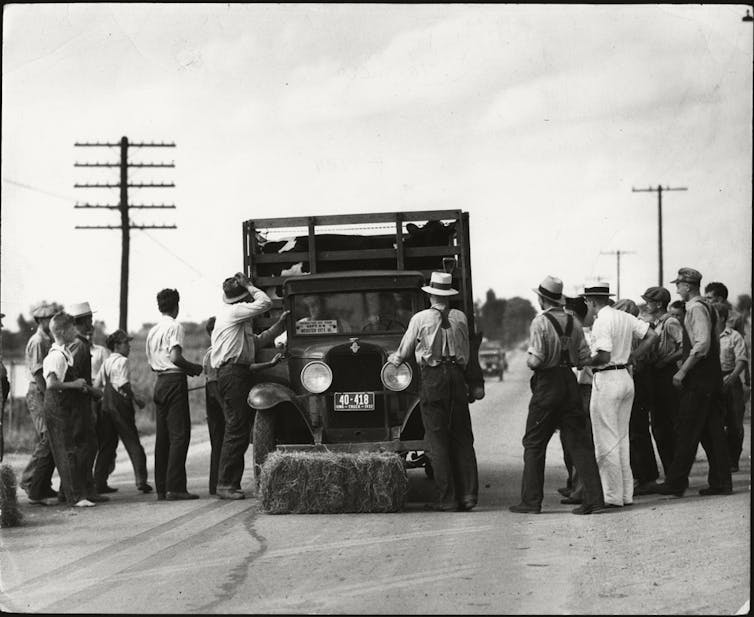

Then there were the slave patrols. Armed Spanish bands called hermandades had hunted runaways in Cuba beginning in the fifteen-thirties, a practice that was adopted by the English in Barbados a century later. It had a lot in common with England’s posse comitatus, a band of stout men that a county sheriff could summon to chase down an escaped criminal. South Carolina, founded by slaveowners from Barbados, authorized its first slave patrol in 1702; Virginia followed in 1726, North Carolina in 1753. Slave patrols married the watch to the militia: serving on patrol was required of all able-bodied men (often, the patrol was mustered from the militia), and patrollers used the hue and cry to call for anyone within hearing distance to join the chase. Neither the watch nor the militia nor the patrols were “police,” who were French, and considered despotic. In North America, the French city of New Orleans was distinctive in having la police: armed City Guards, who wore military-style uniforms and received wages, an urban slave patrol.In 1779, Thomas Jefferson created a chair in “law and police” at the College of William & Mary. The meaning of the word began to change. In 1789, Jeremy Bentham, noting that “police” had recently entered the English language, in something like its modern sense, made this distinction: police keep the peace; justice punishes disorder. (“No justice, no peace!” Black Lives Matter protesters cry in the streets.) Then, in 1797, a London magistrate named Patrick Colquhoun published “A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis.” He, too, distinguished peace kept in the streets from justice administered by the courts: police were responsible for the regulation and correction of behavior and “the prevention and detection of crimes.”It is often said that Britain created the police, and the United States copied it. One could argue that the reverse is true. Colquhoun spent his teens and early twenties in Colonial Virginia, had served as an agent for British cotton manufacturers, and owned shares in sugar plantations in Jamaica. He knew all about slave codes and slave patrols. But nothing came of Colquhoun’s ideas about policing until 1829, when Home Secretary Robert Peel—in the wake of a great deal of labor unrest, and after years of suppressing Catholic rebellions in Ireland, in his capacity as Irish Secretary—persuaded Parliament to establish the Metropolitan Police, a force of some three thousand men, headed by two civilian justices (later called “commissioners”), and organized like an army, with each superintendent overseeing four inspectors, sixteen sergeants, and a hundred and sixty-five constables, who wore coats and pants of blue with black top hats, each assigned a numbered badge and a baton. Londoners came to call these men “bobbies,” for Bobby Peel.It is also often said that modern American urban policing began in 1838, when the Massachusetts legislature authorized the hiring of police officers in Boston. This, too, ignores the role of slavery in the history of the police. In 1829, a Black abolitionist in Boston named David Walker published “An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World,” calling for violent rebellion: “One good black man can put to death six white men.” Walker was found dead within the year, and Boston thereafter had a series of mob attacks against abolitionists, including an attempt to lynch William Lloyd Garrison, the publisher of The Liberator, in 1835. Walker’s words terrified Southern slaveowners. The governor of North Carolina wrote to his state’s senators, “I beg you will lay this matter before the police of your town and invite their prompt attention to the necessity of arresting the circulation of the book.” By “police,” he meant slave patrols: in response to Walker’s “Appeal,” North Carolina formed a statewide “patrol committee.”New York established a police department in 1844; New Orleans and Cincinnati followed in 1852, then, later in the eighteen-fifties, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Baltimore. Population growth, the widening inequality brought about by the Industrial Revolution, and the rise in such crimes as prostitution and burglary all contributed to the emergence of urban policing. So did immigration, especially from Ireland and Germany, and the hostility to immigration: a new party, the Know-Nothings, sought to prevent immigrants from voting, holding office, and becoming citizens. In 1854, Boston disbanded its ancient watch and formally established a police department; that year, Know-Nothings swept the city’s elections.American police differed from their English counterparts: in the U.S., police commissioners, as political appointees, fell under local control, with limited supervision; and law enforcement was decentralized, resulting in a jurisdictional thicket. In 1857, in the Great Police Riot, the New York Municipal Police, run by the mayor’s office, fought on the steps of city hall with the New York Metropolitan Police, run by the state. The Metropolitans were known as the New York Mets. That year, an amateur baseball team of the same name was founded.Also, unlike their British counterparts, American police carried guns, initially their own. In the eighteen-sixties, the Colt Firearms Company began manufacturing a compact revolver called a Pocket Police Model, long before the New York Metropolitan Police began issuing service weapons. American police carried guns because Americans carried guns, including Americans who lived in parts of the country where they hunted for food and defended their livestock from wild animals, Americans who lived in parts of the country that had no police, and Americans who lived in parts of North America that were not in the United States. Outside big cities, law-enforcement officers were scarce. In territories that weren’t yet states, there were U.S. marshals and their deputies, officers of the federal courts who could act as de-facto police, but only to enforce federal laws. If a territory became a state, its counties would elect sheriffs. Meanwhile, Americans became vigilantes, especially likely to kill indigenous peoples, and to lynch people of color. Between 1840 and the nineteen-twenties, mobs, vigilantes, and law officers, including the Texas Rangers, lynched some five hundred Mexicans and Mexican-Americans and killed thousands more, not only in Texas but also in territories that became the states of California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. A San Francisco vigilance committee established in 1851 arrested, tried, and hanged people; it boasted a membership in the thousands. An L.A. vigilance committee targeted and lynched Chinese immigrants.The U.S. Army operated as a police force, too. After the Civil War, the militia was organized into seven new departments of permanent standing armies: the Department of Dakota, the Department of the Platte, the Department of the Missouri, the Department of Texas, the Department of Arizona, the Department of California, and the Department of the Columbian. In the eighteen-seventies and eighties, the U.S. Army engaged in more than a thousand combat operations against Native peoples. In 1890, at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, following an attempt to disarm a Lakota settlement, a regiment of cavalrymen massacred hundreds of Lakota men, women, and children. Nearly a century later, in 1973, F.B.I. agents, swat teams, and federal troops and state marshals laid siege to Wounded Knee during a protest over police brutality and the failure to properly punish the torture and murder of an Oglala Sioux man named Raymond Yellow Thunder. They fired more than half a million rounds of ammunition and arrested more than a thousand people. Today, according to the C.D.C., Native Americans are more likely to be killed by the police than any other racial or ethnic group.Modern American policing began in 1909, when August Vollmer became the chief of the police department in Berkeley, California. Vollmer refashioned American police into an American military. He’d served with the Eighth Army Corps in the Philippines in 1898. “For years, ever since Spanish-American War days, I’ve studied military tactics and used them to good effect in rounding up crooks,” he later explained. “After all we’re conducting a war, a war against the enemies of society.” Who were those enemies? Mobsters, bootleggers, socialist agitators, strikers, union organizers, immigrants, and Black people.To domestic policing, Vollmer and his peers adapted the kinds of tactics and weapons that had been deployed against Native Americans in the West and against colonized peoples in other parts of the world, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, as the sociologist Julian Go has demonstrated. Vollmer instituted a training model imitated all over the country, by police departments that were often led and staffed by other veterans of the United States wars of conquest and occupation. A “police captain or lieutenant should occupy exactly the same position in the public mind as that of a captain or lieutenant in the United States army,” Detroit’s commissioner of police said. (Today’s police officers are disproportionately veterans of U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, many suffering from post-traumatic stress. The Marshall Project, analyzing data from the Albuquerque police, found that officers who are veterans are more likely than their non-veteran counterparts to be involved in fatal shootings. In general, they are more likely to use force, and more likely to fire their guns.)Vollmer-era police enforced a new kind of slave code: Jim Crow laws, which had been passed in the South beginning in the late eighteen-seventies and upheld by the Supreme Court in 1896. William G. Austin became Savannah’s chief of police in 1907. Earlier, he had earned a Medal of Honor for his service in the U.S. Cavalry at Wounded Knee; he had also fought in the Spanish-American War. By 1916, African-American churches in the city were complaining to Savannah newspapers about the “whole scale arrests of negroes because they are negroes—arrests that would not be made if they were white under similar circumstances.” African-Americans also confronted Jim Crow policing in the Northern cities to which they increasingly fled. James Robinson, Philadelphia’s chief of police beginning in 1912, had served in the Infantry during the Spanish-American War and the Philippine-American War. He based his force’s training on manuals used by the U.S. Army at Leavenworth. Go reports that, in 1911, about eleven per cent of people arrested were African-American; under Robinson, that number rose to 14.6 per cent in 1917. By the nineteen-twenties, a quarter of those arrested were African-Americans, who, at the time, represented just 7.4 per cent of the population.Progressive Era, Vollmer-style policing criminalized Blackness, as the historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad argued in his 2010 book, “The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America.” Police patrolled Black neighborhoods and arrested Black people disproportionately; prosecutors indicted Black people disproportionately; juries found Black people guilty disproportionately; judges gave Black people disproportionately long sentences; and, then, after all this, social scientists, observing the number of Black people in jail, decided that, as a matter of biology, Black people were disproportionately inclined to criminality.More recently, between the New Jim Crow and the criminalization of immigration and the imprisonment of immigrants in detention centers, this reality has only grown worse. “By population, by per capita incarceration rates, and by expenditures, the United States exceeds all other nations in how many of its citizens, asylum seekers, and undocumented immigrants are under some form of criminal justice supervision,” Muhammad writes in a new preface to his book. “The number of African American and Latinx people in American jails and prisons today exceeds the entire populations of some African, Eastern European, and Caribbean countries.”Policing grew harsher in the Progressive Era, and, with the emergence of state-police forces, the number of police grew, too. With the rise of the automobile, some, like California’s, began as “highway patrols.” Others, including the state police in Nevada, Colorado, and Oregon, began as the private paramilitaries of industrialists which employed the newest American immigrants: Hungarians, Italians, and Jews. Industrialists in Pennsylvania established the Iron and Coal Police to end strikes and bust unions, including the United Mine Workers; in 1905, three years after an anthracite-coal strike, the Pennsylvania State Police started operations. “One State Policeman should be able to handle one hundred foreigners,” its new chief said.ANTI ITALIAN HYSTERIA ABOUT ANARCHISTS ARREST OF SACCO AND VANZETTI

The U.S. Border Patrol began in 1924, the year that Congress restricted immigration from southern Europe. At the insistence of Southern and Western agriculturalists, Congress exempted Mexicans from its new immigration quotas in order to allow migrant workers to enter the United States. The Border Patrol began as a relatively small outfit responsible for enforcing federal immigration law, and stopping smugglers, at all of the nation’s borders. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, it grew to a national quasi-military focussed on policing the southern border in campaigns of mass arrest and forced deportation of Mexican immigrants, aided by local police like the notoriously brutal L.A.P.D., as the historian Kelly Lytle Hernández has chronicled. What became the Chicano movement began in Southern California, with Mexican immigrants’ protests of the L.A.P.D. during the first half of the twentieth century, even as a growing film industry cranked out features about Klansmen hunting Black people, cowboys killing Indians, and police chasing Mexicans. More recently, you can find an updated version of this story in L.A. Noire, a video game set in 1947 and played from the perspective of a well-armed L.A.P.D. officer, who, driving along Sunset Boulevard, passes the crumbling, abandoned sets from D. W. Griffith’s 1916 film “Intolerance,” imagined relics of an unforgiving age.

Two kinds of police appeared on mid-century American television. The good guys solved crime on prime-time police procedurals like “Dragnet,” starting in 1951, and “Adam-12,” beginning in 1968 (both featured the L.A.P.D.). The bad guys shocked America’s conscience on the nightly news: Arkansas state troopers barring Black students from entering Little Rock Central High School, in 1957; Birmingham police clubbing and arresting some seven hundred Black children protesting segregation, in 1963; and Alabama state troopers beating voting-rights marchers at Selma, in 1965. These two faces of policing help explain how, in the nineteen-sixties, the more people protested police brutality, the more money governments gave to police departments.

“You get the wine.”

Cartoon by Pia Guerra and Ian Boothby

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson declared a “war on crime,” and asked Congress to pass the Law Enforcement Assistance Act, under which the federal government would supply local police with military-grade weapons, weapons that were being used in the war in Vietnam. During riots in Watts that summer, law enforcement killed thirty-one people and arrested more than four thousand; fighting the protesters, the head of the L.A.P.D. said, was “very much like fighting the Viet Cong.” Preparing for a Senate vote just days after the uprising ended, the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee said, “For some time, it has been my feeling that the task of law enforcement agencies is really not much different from military forces; namely, to deter crime before it occurs, just as our military objective is deterrence of aggression.”

As Elizabeth Hinton reported in “From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America,” the “frontline soldiers” in Johnson’s war on crime—Vollmer-era policing all over again—spent a disproportionate amount of time patrolling Black neighborhoods and arresting Black people. Policymakers concluded from those differential arrest rates that Black people were prone to criminality, with the result that police spent even more of their time patrolling Black neighborhoods, which led to a still higher arrest rate. “If we wish to rid this country of crime, if we wish to stop hacking at its branches only, we must cut its roots and drain its swampy breeding ground, the slum,” Johnson told an audience of police policymakers in 1966. The next year, riots broke out in Newark and Detroit. “We ain’t rioting agains’ all you whites,” one Newark man told a reporter not long before being shot dead by police. “We’re riotin’ agains’ police brutality.” In Detroit, police arrested more than seven thousand people.

Johnson’s Great Society essentially ended when he asked Congress to pass the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act, which had the effect of diverting money from social programs to policing. This magazine called it “a piece of demagoguery devised out of malevolence and enacted in hysteria.” James Baldwin attributed its “irresponsible ferocity” to “some pale, compelling nightmare—an overwhelming collection of private nightmares.” The truth was darker, as the sociologist Stuart Schrader chronicled in his 2019 book, “Badges Without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing.” During the Cold War, the Office of Public Safety at the U.S.A.I.D. provided assistance to the police in at least fifty-two countries, and training to officers from nearly eighty, for the purpose of counter-insurgency—the suppression of an anticipated revolution, that collection of private nightmares; as the O.P.S. reported, it contributed “the international dimension to the Administration’s War on Crime.” Counter-insurgency boomeranged, and came back to the United States, as policing.

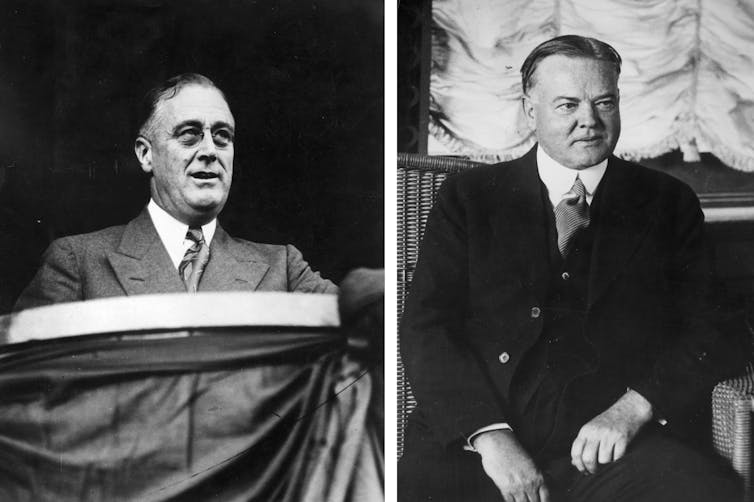

In 1968, Johnson’s new crime bill established the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, within the Department of Justice, which, in the next decade and a half, disbursed federal funds to more than eighty thousand crime-control projects. Even funds intended for social projects—youth employment, for instance, along with other health, education, housing, and welfare programs—were distributed to police operations. With Richard Nixon, any elements of the Great Society that had survived the disastrous end of Johnson’s Presidency were drastically cut, with an increased emphasis on policing, and prison-building. More Americans went to prison between 1965 and 1982 than between 1865 and 1964, Hinton reports. Under Ronald Reagan, still more social services were closed, or starved of funding until they died: mental hospitals, health centers, jobs programs, early-childhood education. By 2016, eighteen states were spending more on prisons than on colleges and universities. Activists who today call for defunding the police argue that, for decades, Americans have been defunding not only social services but, in many states, public education itself. The more frayed the social fabric, the more police have been deployed to trim the dangling threads.

The blueprint for law enforcement from Nixon to Reagan came from the Harvard political scientist James Q. Wilson between 1968, in his book “Varieties of Police Behavior,” and 1982, in an essay in The Atlantic titled “Broken Windows.” On the one hand, Wilson believed that the police should shift from enforcing the law to maintaining order, by patrolling on foot, and doing what came to be called “community policing.” (Some of his recommendations were ignored: Wilson called for other professionals to handle what he termed the “service functions” of the police—“first aid, rescuing cats, helping ladies, and the like”—which is a reform people are asking for today.) On the other hand, Wilson called for police to arrest people for petty crimes, on the theory that they contributed to more serious crimes. Wilson’s work informed programs like Detroit’s stress (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets), begun in 1971, in which Detroit police patrolled the city undercover, in disguises that included everything from a taxi-driver to a “radical college professor,” and killed so many young Black men that an organization of Black police officers demanded that the unit be disbanded. The campaign to end stress arguably marked the very beginnings of police abolitionism. stress defended its methods. “We just don’t walk up and shoot somebody,” one commander said. “We ask him to stop. If he doesn’t, we shoot.”

For decades, the war on crime was bipartisan, and had substantial support from the Congressional Black Caucus. “Crime is a national-defense problem,” Joe Biden said in the Senate, in 1982. “You’re in as much jeopardy in the streets as you are from a Soviet missile.” Biden and other Democrats in the Senate introduced legislation that resulted in the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984. A decade later, as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Biden helped draft the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, whose provisions included mandatory sentencing. In May, 1991, two months after the Rodney King beating, Biden introduced the Police Officers’ Bill of Rights, which provided protections for police under investigation. The N.R.A. first endorsed a Presidential candidate, Reagan, in 1980; the Fraternal Order of Police, the nation’s largest police union, first endorsed a Presidential candidate, George H. W. Bush, in 1988. In 1996, it endorsed Bill Clinton.

Partly because of Biden’s record of championing law enforcement, the National Association of Police Organizations endorsed the Obama-Biden ticket in 2008 and 2012. In 2014, after police in Ferguson, Missouri, shot Michael Brown, the Obama Administration established a task force on policing in the twenty-first century. Its report argued that police had become warriors when what they really should be is guardians. Most of its recommendations were never implemented.

In 2016, the Fraternal Order of Police endorsed Donald Trump, saying that “our members believe he will make America safe again.” Police unions are lining up behind Trump again this year. “We will never abolish our police or our great Second Amendment,” Trump said at Mt. Rushmore, on the occasion of the Fourth of July. “We will not be intimidated by bad, evil people.”

Trump is not the king; the law is king. The police are not the king’s men; they are public servants. And, no matter how desperately Trump would like to make it so, policing really isn’t a partisan issue. Out of the stillness of the shutdown, the voices of protest have roared like summer thunder. An overwhelming majority of Americans, of both parties, support major reforms in American policing. And a whole lot of police, defying their unions, also support those reforms.

Those changes won’t address plenty of bigger crises, not least because the problem of policing can’t be solved without addressing the problem of guns. But this much is clear: the polis has changed, and the police will have to change, too.

Published in the print edition of the July 20, 2020, issue, with the headline “The Long Blue Line.”

Jill Lepore is a professor of history at Harvard and the host of the podcast “The Last Archive.” Her fourteenth book, “If Then,” will be published in September