Clemency director Chinonye Chukwu: ‘Society doesn’t care about black women’s humanity’

As her award-winning and chilling prison drama comes to UK screens, the writer and director tells Kuba Shand-Baptiste about creating complex female leads and why it’s time to smash the system

'We're not used to seeing black women as fully realised human beings who are not solely defined by their race and gender' ( Photo by Michael Buckner/Deadline/REX )

They say dying by lethal injection feels like being burnt alive. The deadly, usually three-drug cocktail has the highest botch rate of all the methods used to kill prisoners in the United States.

It is also the most commonly used. That’s the ugly truth we’re confronted with mere minutes into Chinonye Chukwu’s gut-punching film Clemency. We watch a prisoner die slowly and painfully, his howls at the various attempts to jab him haunting the rest of the film. As tough a watch as it is, there’s no looking away, no matter how much you, the viewer, or Bernadine, the prison warden protagonist played by Alfre Woodard, wants to.

It’s no wonder that Clemency took the Grand Jury Prize Award at Sundance last year, making Chukwu the first black woman to do so. The cast is heavyweight, with Aldis Hodge, The West Wing’s Richard Schiff, The Wire’s Wendell Pierce and Danielle Brooks of Orange Is The New Black appearing alongside Woodard. And Chukwu’s thoughtful storytelling pulls you into the punitive, unforgiving hellscape of the US prison system in a way that few film-makers have done in the past. On the phone from LA, she calls her Sundance win “bittersweet”, adding, “I wish I was the 10th black woman, you know?”

Chukwu isn’t yet a household name but she is a part of some of the most anticipated projects this year. She’s directing the first two episodes of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s long-awaited TV adaptation of Americanah, starring Lupita Nyong’o, and the biopic of Elaine Brown, the first and only woman to chair the Black Panther Party. She speaks animatedly about this all from the off, and if she’s weary about sitting through yet another interview of several that day, her cheery demeanour masks it entirely. “I feel great!” she exclaims. “It’s been an incredibly exciting time since winning but it’s also been incredibly growthful”.

For Chukwu, it’s important to stay as true to herself as the characters in her films. The 35-year-old film-maker was born in Nigeria, and moved to Alaska when she was a baby. There, she grew up navigating her experience as a black girl in a city with a tiny black population, and an even smaller Nigerian-American population. She oscillated between the two experiences of Americanness and Nigerianness, feeling ill-matched for either one at various points of her life, which she says “has really made me live in a lot of grey areas when it comes to identity”.

Read more

Viola Davis says The Help was ‘created in cesspool of systemic racism’

Those grey areas have come to inform her work, too. Her characters have a rich complexity that is no doubt partly inspired by unique experiences she had growing up – her 2012 film Alaska-Land depicted two estranged Nigerian-American siblings who reunite in their hometown of Fairbanks. “What makes some of the most compelling storytelling,” says Chukwu, “is when we’re not so binary but show the paradoxes that make up our human existence. [Those are the] areas that I tend to live in, in my filmmaking and in my storytelling. And so, my background has forced me to really live in that when I create characters.”

The story of Americanah particularly resonated with her, she says. The book follows a Nigerian woman who goes to university in the US and wakes up to an entirely new world, not just in terms of culture, but how she sees herself. Chukwu says the story in many ways parallels her childhood experiences of being othered. “I have a deep connection and passion for Americanah, for obvious reasons,” she says. “I’m so excited to bring it to the screen because [Hollywood] tends to essentialise or stereotype ‘Africa and Africans’. But Americanah explores a lot of layers and identities of self within a very specific cultural context that I think a lot of people will be able to see themselves in.”

She’s enthusiastic too about bringing the first female Black Panther leader’s story to a wider audience. “Elaine Brown’s is another story that we haven’t seen on screen,” she says, particularly “this powerful journey of self that this black woman character goes on”.

The powerful journey of self is also central to Clemency, which follows Bernadine Williams, a prison warden who carries out executions in a maximum security prison. She is tortured by her death row duty and how it infiltrates and contrasts with every aspect of her life outside her work. Her profession requires unflinching stoicism, while her humanity and personal life is every bit as gentle and fragile as the lives she’s in charge of ending. That sense of duality could easily work as an analogy for the experiences of black women in the US and beyond. Not only does society view us as unbreakable or incapable of vulnerability, it requires us to fit into those moulds, betraying the full, delicate and complicated lives we’ve always led.

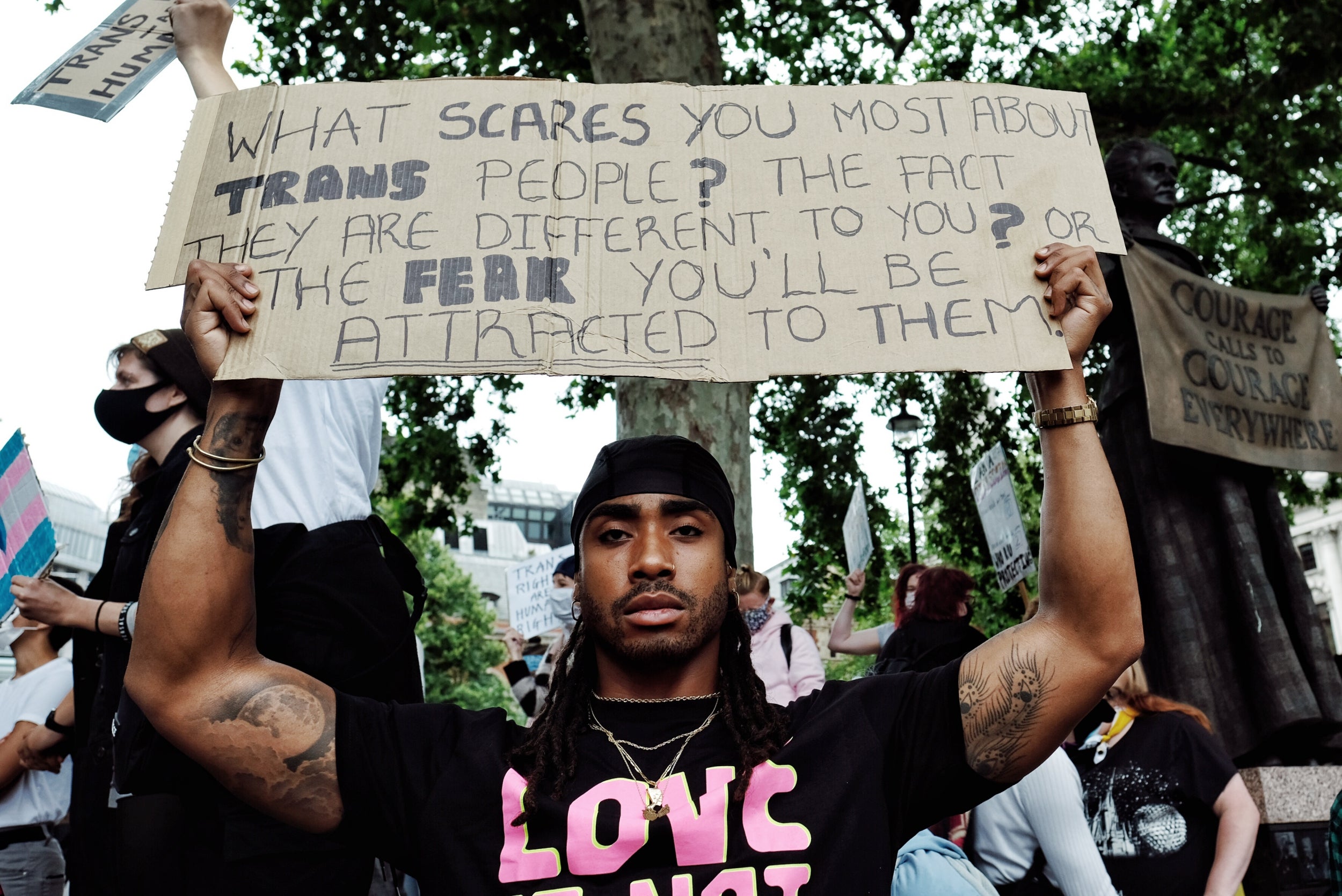

Chukwu says that casting Bernadine as a black woman “inherently complicates” Clemency’s narrative “because we’re not used to seeing black women as fully realised human beings who are not solely defined by their race and gender”, or by male characters. She says that these are “stereotypical and archetypical expectations” that audiences have developed about black female characters and Bernadine “subverts” them all. She is dutiful and professional to almost infuriating degrees. She is loved. She is loathed. She is also terrified.

Despite some recent, marginal improvement in the film industry when it comes to representation, Chukwu says that black female characters are largely still not given the space to be complex. When I ask why, she tells me, matter-of-factly, “I mean, society doesn’t regard black women. Society doesn’t care about black women’s humanity and so we see the extension of that on screen. We’re disregarded and dehumanised and discredited in real life every single day. That doesn’t stop in cinema.”

The dehumanisation of black women and people more broadly is something Chukwu has pushed back against throughout her career. After graduating from studying film at university, she made 2012 short film Bottom, about the push and pull of power between a lesbian couple. A Long Walk in 2013 followed, based on an excerpt from her former professor’s memoir about a boy who wishes to dress in feminine clothing but is punished by his father.

Clemency, however, is considered her most hard-hitting film yet. Chukwu was inspired to write the story after the execution of Troy Davis in 2011, one of many cases now thought of as a precursor to the establishment of the Black Lives Matter movement. Though it was released in the US in December 2019, she says that looking back at it now, against the backdrop of ongoing protests following numerous incidents of racist police brutality in the US and around the world, makes her film all the more urgent.

“One of my intentions with making Clemency was to inspire audiences to question the prison industrial complex and specifically capital punishment,” she says. “What we’re [seeing] now is that same thing. We’re interrogating criminal legal practices and wondering: are they really forms of justice, or are they an extension of white supremacist capitalist systems that are connected to enslavement?”

The answer to the latter, at least in Chukwu’s opinion, is yes. It’s the same when it comes to police abolition. “Part of what the call for defunding the police is rooted in,” she continues, emphatically, “is also this larger abolitionist framework where we need to rethink what the function and the necessity of policing is and realise that the historical roots of policing came from enslavement.”

Those grey areas have come to inform her work, too. Her characters have a rich complexity that is no doubt partly inspired by unique experiences she had growing up – her 2012 film Alaska-Land depicted two estranged Nigerian-American siblings who reunite in their hometown of Fairbanks. “What makes some of the most compelling storytelling,” says Chukwu, “is when we’re not so binary but show the paradoxes that make up our human existence. [Those are the] areas that I tend to live in, in my filmmaking and in my storytelling. And so, my background has forced me to really live in that when I create characters.”

The story of Americanah particularly resonated with her, she says. The book follows a Nigerian woman who goes to university in the US and wakes up to an entirely new world, not just in terms of culture, but how she sees herself. Chukwu says the story in many ways parallels her childhood experiences of being othered. “I have a deep connection and passion for Americanah, for obvious reasons,” she says. “I’m so excited to bring it to the screen because [Hollywood] tends to essentialise or stereotype ‘Africa and Africans’. But Americanah explores a lot of layers and identities of self within a very specific cultural context that I think a lot of people will be able to see themselves in.”

She’s enthusiastic too about bringing the first female Black Panther leader’s story to a wider audience. “Elaine Brown’s is another story that we haven’t seen on screen,” she says, particularly “this powerful journey of self that this black woman character goes on”.

The powerful journey of self is also central to Clemency, which follows Bernadine Williams, a prison warden who carries out executions in a maximum security prison. She is tortured by her death row duty and how it infiltrates and contrasts with every aspect of her life outside her work. Her profession requires unflinching stoicism, while her humanity and personal life is every bit as gentle and fragile as the lives she’s in charge of ending. That sense of duality could easily work as an analogy for the experiences of black women in the US and beyond. Not only does society view us as unbreakable or incapable of vulnerability, it requires us to fit into those moulds, betraying the full, delicate and complicated lives we’ve always led.

Chukwu says that casting Bernadine as a black woman “inherently complicates” Clemency’s narrative “because we’re not used to seeing black women as fully realised human beings who are not solely defined by their race and gender”, or by male characters. She says that these are “stereotypical and archetypical expectations” that audiences have developed about black female characters and Bernadine “subverts” them all. She is dutiful and professional to almost infuriating degrees. She is loved. She is loathed. She is also terrified.

Despite some recent, marginal improvement in the film industry when it comes to representation, Chukwu says that black female characters are largely still not given the space to be complex. When I ask why, she tells me, matter-of-factly, “I mean, society doesn’t regard black women. Society doesn’t care about black women’s humanity and so we see the extension of that on screen. We’re disregarded and dehumanised and discredited in real life every single day. That doesn’t stop in cinema.”

The dehumanisation of black women and people more broadly is something Chukwu has pushed back against throughout her career. After graduating from studying film at university, she made 2012 short film Bottom, about the push and pull of power between a lesbian couple. A Long Walk in 2013 followed, based on an excerpt from her former professor’s memoir about a boy who wishes to dress in feminine clothing but is punished by his father.

Clemency, however, is considered her most hard-hitting film yet. Chukwu was inspired to write the story after the execution of Troy Davis in 2011, one of many cases now thought of as a precursor to the establishment of the Black Lives Matter movement. Though it was released in the US in December 2019, she says that looking back at it now, against the backdrop of ongoing protests following numerous incidents of racist police brutality in the US and around the world, makes her film all the more urgent.

“One of my intentions with making Clemency was to inspire audiences to question the prison industrial complex and specifically capital punishment,” she says. “What we’re [seeing] now is that same thing. We’re interrogating criminal legal practices and wondering: are they really forms of justice, or are they an extension of white supremacist capitalist systems that are connected to enslavement?”

The answer to the latter, at least in Chukwu’s opinion, is yes. It’s the same when it comes to police abolition. “Part of what the call for defunding the police is rooted in,” she continues, emphatically, “is also this larger abolitionist framework where we need to rethink what the function and the necessity of policing is and realise that the historical roots of policing came from enslavement.”

Alfre Woodard as prison officer Bernadine in ‘Clemency’ (Neon)

She says she opened Clemency with a scene that questions the ethics of the death penalty because she “wanted to set up the stakes from the beginning” and it’s a chilling reminder of another practice that she says is in desperate need of dismantling.

Are people coming around to that possibility these days?

“Slowly but surely,” she says. “I think that some states are questioning it more on economic grounds because it’s incredibly expensive to maintain. But I also think morally, more and more people are starting to go against it, or at least question if it really does help provide any form of justice in our society.”

Chukwu’s films certainly make you question everything about society: the systems we unreservedly accept as gospel; the atrocities we ignore; the identities and communities we fail time and time again. But the film has more poetic moments, too. The part of the film that particularly stayed with me was a passage from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, read by Wendell Pierce as Bernadine’s school teacher husband Jonathan:

“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allen Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fibre and liquids – and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, because people refuse to see me…”

Those words encapsulate the film’s themes, says Chukwu, because “we invisibilise people who are incarcerated. We invisibilise black people, poor people, marginalised groups of people.” For now, at least, Chukwu is making the task of being invisible in cinema that much harder.