Though air pollution has declined by nearly 70 percent across much of the United States, new research showed that the most polluted places in 35 years ago are still the most polluted today. Photo by Etienne Laurent/EPA-EFE

July 31 (UPI) -- The amount of particulate matter in the air in the United States has declined significantly over the last several decades, but new research suggests disparities between the most and least polluted communities persist.

Dozens of studies have previously confirmed the reality of environmental inequity. Poorer communities and minority communities are more likely to be exposed to air pollution than those living in wealthier neighborhoods.

But until now, little analysis had been done to understand if and how those disparities change over time, researchers say.

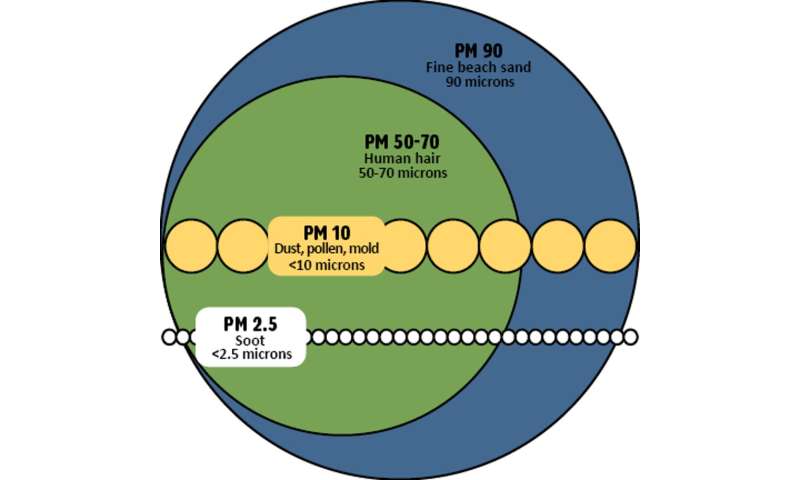

For the new study, researchers at the University of Virginia combined 36-years worth of records on fine particulate matter, particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, with U.S. census data in order to rank communities from the least to the most polluted for each year between 1981 and 2016.

The data -- detailed Friday in the journal Science -- revealed a remarkable level of continuity. Across the 36-year timeline, the most polluted places remained the most polluted places.

"Our findings call attention to the scope, scale, and remarkable persistence of air pollution disparities in the United States," lead study author Jonathan Colmer, an assistant professor of economics at UVA, told UPI.

Studies suggest that each year dirty air sends some 5.5 million people around the world to an early grave. But in the United States, the number of deaths caused by air pollution has been steadily dropping. One study determined total air pollution deaths were reduced by half between 1990 and 2010.

RELATED Air, water benefits of COVID-19 lockdowns may not last, experts say

If there is a silver lining to the latest research, it is that communities rich and poor, black and white, have shared equally in the air pollution reductions measured over the last few decades.

"We found that pollution reductions were larger in areas that were more polluted in 1981 but these locations were starting from a much higher starting point," study co-author Jay Shimshack told UPI.

"Disadvantaged neighborhoods did not experience disproportionate reductions in fine particulate matter air pollution," said Shimshack, an associate professor of public policy and economics at UVA. "Broadly speaking, everywhere experienced a 60 to 70 percent reduction between 1981 and 2016."

RELATED Small reductions in air pollution can reduce heart disease threat

While air quality is better than it used to be, particulate matter pollution remains a serious environmental problem in many parts of the country, and the latest research suggests it's still a much bigger problem in poorer communities and communities of color.

Breathing dirty air can trigger and exacerbate a variety of health problems, including asthma, diabetes, heart disease and some cancers. The health problems made worse by pollution are many of the same problems that already disproportionately impact minority communities.

The authors of the latest study don't have specific policy prescriptions, but they hope to study the impacts of political advocacy and policy reforms on pollution in the near future.

"We still don't fully understand why disparities exist, let alone why they persist," Colmer said. "Better answers to these questions will lead to sharper policy recommendations."

For now, they said they hope that by simply detailing the problem, they can begin to plot a path for progress -- and inspire others to do the same.

"Federal and state guidelines aim for all people to enjoy the same degree of protection from environmental hazards and argue that no groups should bear a disproportionate share of pollution," Shimshack said. "On this front we are falling short."

Credit: The Ohio State University

Credit: The Ohio State University