New smartphone game lets you solve real-world ecological puzzles

by Imperial College London

EcoBuilder, which is downloadable now on smartphones and tablets, teaches players how ecosystems work and aims to crowdsource solutions to unsolved ecological puzzles.

Ecosystem research looks at how animals and plants interact with each other and their environment. Climate change and other human interventions pose ongoing threats to how ecosystems function, resulting in changes to carbon flows and even extinctions of certain species.

EcoBuilder lets players build their own ecosystem of plants and animals. They throw together a bunch of species of different shapes and sizes, decide who eats who within the confines of the game, and depending on their decisions species will either survive or go extinct.

The in-game processes that decide extinction and survival are modelled using the same equations used by scientists to study real world ecosystems. This means that natural phenomena can be reproduced inside the game, creating ecosystems that behave in realistic ways to provide real-world answers.

Therefore, players' successful game strategies could make their way into the research literature and expand our understanding of ecology, potentially helping conservationists to save endangered species and conserve biodiversity.

Jonathan Zheng, who developed the game as part of his Ph.D. in the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Imperial, said: "This game presents a fun opportunity to contribute to real research that could change policy and affect our natural world. Players will learn about various ecological phenomena along the way, and their solutions could help real researchers to understand ecosystems better."

Canine inspiration

The game's designers took inspiration from a project to save the habitat of Yellowstone National Park in the U.S.. In 1926, wolves were declared extinct in the park due to a lack of hunting regulations. The lack of wolves meant that the population of elk boomed. The elk in their vast numbers ate too much vegetation and, in turn, caused smaller animals such as beavers and fish to struggle and eventually go extinct as well.

Following failed attempts to control the elk population by hunting and moving them, ecologists reintroduced 14 wolves into the park from Canada in 1995.

The new wolves suppressed the elk, triggering a chain of effects rippling through the ecosystem. Fewer elk meant plants could grow bigger and taller; more plants meant beavers could return and build dams again; the dams drew fish and more water back into the rivers and lakes. Thus, the ecosystem was saved.

However, the Yellowstone ecosystem still hasn't recovered to pre-1926 levels—a conundrum the researchers say highlights how complex and sensitive to human intervention these communities are.

In EcoBuilder, players can make the same sorts of decisions that ecologists made in Yellowstone.

Project co-supervisor Dr. Dan Goodman, also of the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Imperial, said: "Since scientific understanding informs governmental policy, perhaps one day the strategies designed by players may influence decisions made by real conservationists, just like those made to reintroduce wolves back to Yellowstone park."

The game

EcoBuilder is divided into two 'Worlds'.

The first world, 'Learning World', gradually teaches players how different sizes and biomasses of animals and plants interact with one another, using colourful graphics and characters. In the scenarios presented, the researchers already know the 'answers', or the best ways to preserve the ecosystem without extinctions.

Once players master the Learning World they move on to the Research World, which presents ecological puzzles to which the researchers are unsure of the answers, making decisions about which species to introduce and seeing who survives and who goes extinct.

The research team collects data on players' solutions within both Worlds, but hope that players in the Research World might help solve real-world ecological puzzles that are reflected in the game.

Project co-supervisor Dr. Samraat Pawar, of the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: "As well as crowdsourcing the intellectual power of the general public, the game has a powerful capacity for outreach and teaching purposes, as players learn how ecosystems function and why they may collapse from even small changes to their structure."

The researchers hope players will find interesting and unique strategies that lead to the healthiest ecosystems, which researchers can learn from—a form of 'citizen science'.

Jonathan added: "Raising awareness for environmental issues is as important as ever, especially given the fragility of many ecosystems around the world because of global warming."

What Jenga can teach us about wildlife conservation before it's too late

Provided by Imperial College London

EcoBuilder, which is downloadable now on smartphones and tablets, teaches players how ecosystems work and aims to crowdsource solutions to unsolved ecological puzzles.

Ecosystem research looks at how animals and plants interact with each other and their environment. Climate change and other human interventions pose ongoing threats to how ecosystems function, resulting in changes to carbon flows and even extinctions of certain species.

EcoBuilder lets players build their own ecosystem of plants and animals. They throw together a bunch of species of different shapes and sizes, decide who eats who within the confines of the game, and depending on their decisions species will either survive or go extinct.

The in-game processes that decide extinction and survival are modelled using the same equations used by scientists to study real world ecosystems. This means that natural phenomena can be reproduced inside the game, creating ecosystems that behave in realistic ways to provide real-world answers.

Therefore, players' successful game strategies could make their way into the research literature and expand our understanding of ecology, potentially helping conservationists to save endangered species and conserve biodiversity.

Jonathan Zheng, who developed the game as part of his Ph.D. in the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Imperial, said: "This game presents a fun opportunity to contribute to real research that could change policy and affect our natural world. Players will learn about various ecological phenomena along the way, and their solutions could help real researchers to understand ecosystems better."

Canine inspiration

The game's designers took inspiration from a project to save the habitat of Yellowstone National Park in the U.S.. In 1926, wolves were declared extinct in the park due to a lack of hunting regulations. The lack of wolves meant that the population of elk boomed. The elk in their vast numbers ate too much vegetation and, in turn, caused smaller animals such as beavers and fish to struggle and eventually go extinct as well.

Following failed attempts to control the elk population by hunting and moving them, ecologists reintroduced 14 wolves into the park from Canada in 1995.

The new wolves suppressed the elk, triggering a chain of effects rippling through the ecosystem. Fewer elk meant plants could grow bigger and taller; more plants meant beavers could return and build dams again; the dams drew fish and more water back into the rivers and lakes. Thus, the ecosystem was saved.

However, the Yellowstone ecosystem still hasn't recovered to pre-1926 levels—a conundrum the researchers say highlights how complex and sensitive to human intervention these communities are.

In EcoBuilder, players can make the same sorts of decisions that ecologists made in Yellowstone.

Project co-supervisor Dr. Dan Goodman, also of the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Imperial, said: "Since scientific understanding informs governmental policy, perhaps one day the strategies designed by players may influence decisions made by real conservationists, just like those made to reintroduce wolves back to Yellowstone park."

The game

EcoBuilder is divided into two 'Worlds'.

The first world, 'Learning World', gradually teaches players how different sizes and biomasses of animals and plants interact with one another, using colourful graphics and characters. In the scenarios presented, the researchers already know the 'answers', or the best ways to preserve the ecosystem without extinctions.

Once players master the Learning World they move on to the Research World, which presents ecological puzzles to which the researchers are unsure of the answers, making decisions about which species to introduce and seeing who survives and who goes extinct.

The research team collects data on players' solutions within both Worlds, but hope that players in the Research World might help solve real-world ecological puzzles that are reflected in the game.

Project co-supervisor Dr. Samraat Pawar, of the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: "As well as crowdsourcing the intellectual power of the general public, the game has a powerful capacity for outreach and teaching purposes, as players learn how ecosystems function and why they may collapse from even small changes to their structure."

The researchers hope players will find interesting and unique strategies that lead to the healthiest ecosystems, which researchers can learn from—a form of 'citizen science'.

Jonathan added: "Raising awareness for environmental issues is as important as ever, especially given the fragility of many ecosystems around the world because of global warming."

What Jenga can teach us about wildlife conservation before it's too late

Provided by Imperial College London

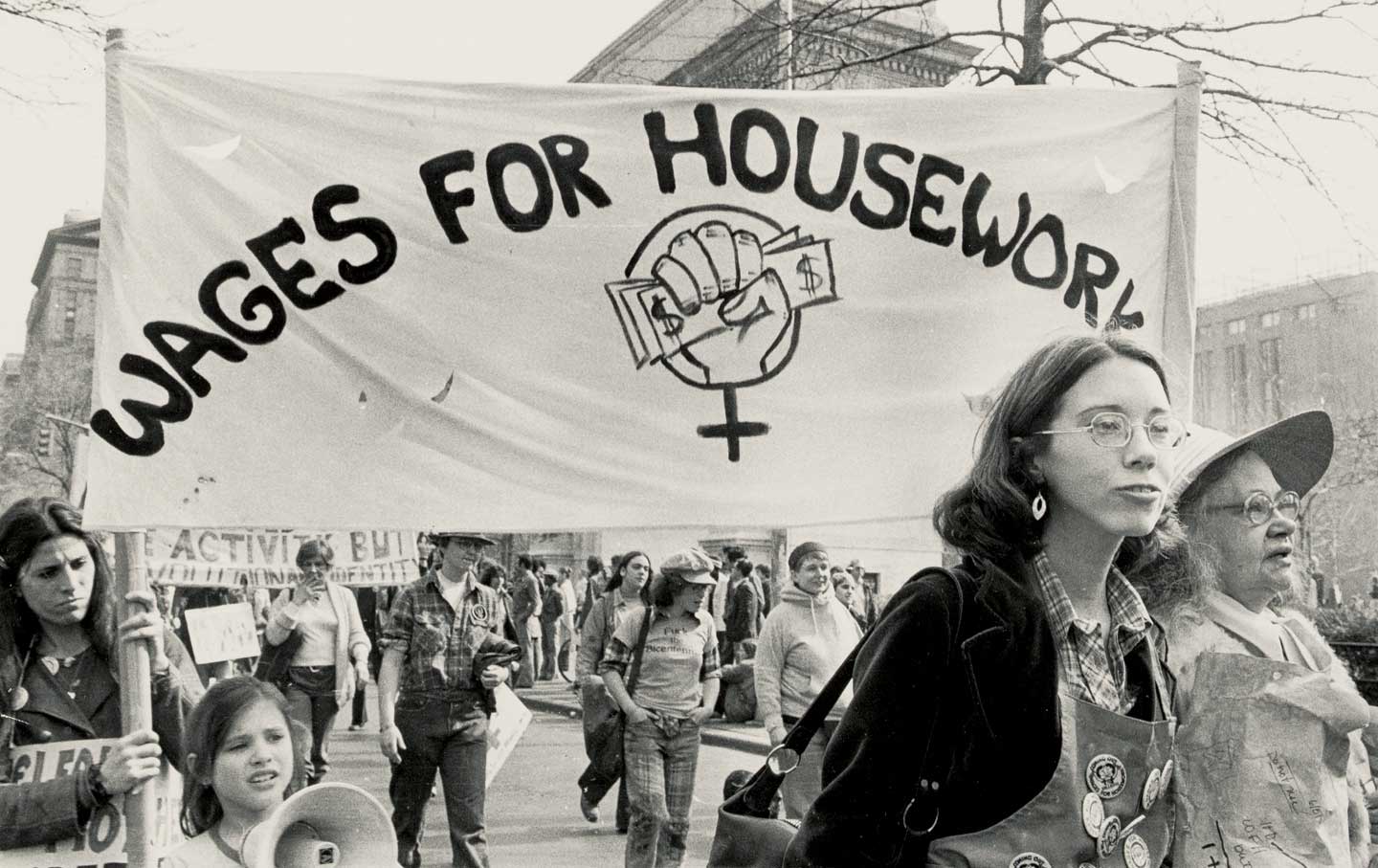

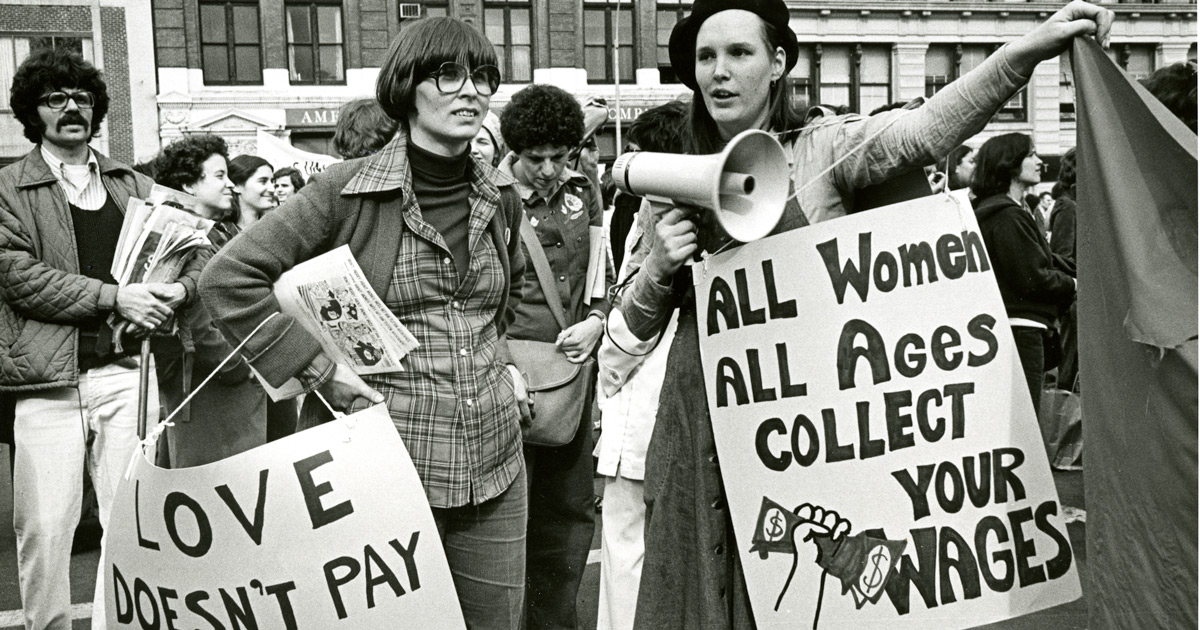

Impacted by the pandemic, many women are trading present and future earnings and putting a costly gap in their resumes, says Dr. Foster. Credit: Thought Catalog

Impacted by the pandemic, many women are trading present and future earnings and putting a costly gap in their resumes, says Dr. Foster. Credit: Thought Catalog