First gene knockout in cephalopod achieved

CRISPR CRITTERS

by Marine Biological Laboratory

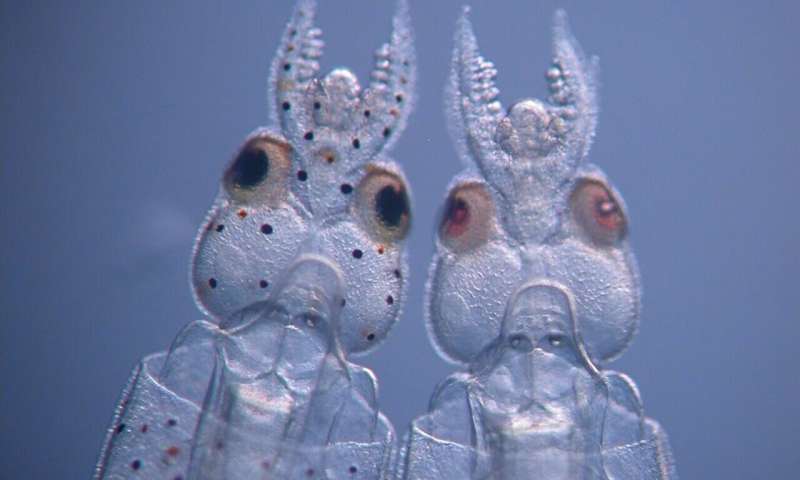

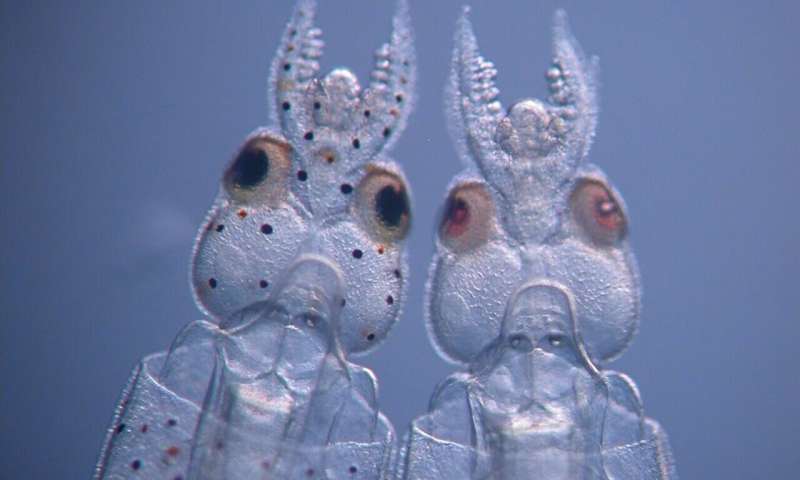

Longfin inshore squid (Doryteuthis pealeii) hatchlings. On the left is a control hatchling; note the black and reddish brown chromatophores evenly placed across its mantle, head and tentacles. In contrast, the embryo on the right was injected with CRISPR-Cas9 targeting a pigmentation gene (Tryptophan 2,3 Dioxygenase) before the first cell division ; it has very few pigmented chromatophores and light pink to red eyes. Credit: Karen Crawford

A team at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) has achieved the first gene knockout in a cephalopod using the squid Doryteuthis pealeii, an exceptionally important research organism in biology for nearly a century. The milestone study, led by MBL Senior Scientist Joshua Rosenthal and MBL Whitman Scientist Karen Crawford, is reported in the July 30 issue of Current Biology.

The team used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to knock out a pigmentation gene in squid embryos, which eliminated pigmentation in the eye and in skin cells (chromatophores) with high efficiency.

"This is a critical first step toward the ability to knock out—and knock in—genes in cephalopods to address a host of biological questions," Rosenthal says.

Cephalopods (squid, octopus and cuttlefish) have the largest brain of all invertebrates, a distributed nervous system capable of instantaneous camouflage and sophisticated behaviors, a unique body plan, and the ability to extensively recode their own genetic information within messenger RNA, along with other distinctive features. These open many avenues for study and have applications in a wide range of fields, from evolution and development, to medicine, robotics, materials science, and artificial intelligence.

The ability to knock out a gene to test its function is an important step in developing cephalopods as genetically tractable organisms for biological research, augmenting the handful of species that currently dominate genetic studies, such as fruit flies, zebrafish, and mice.

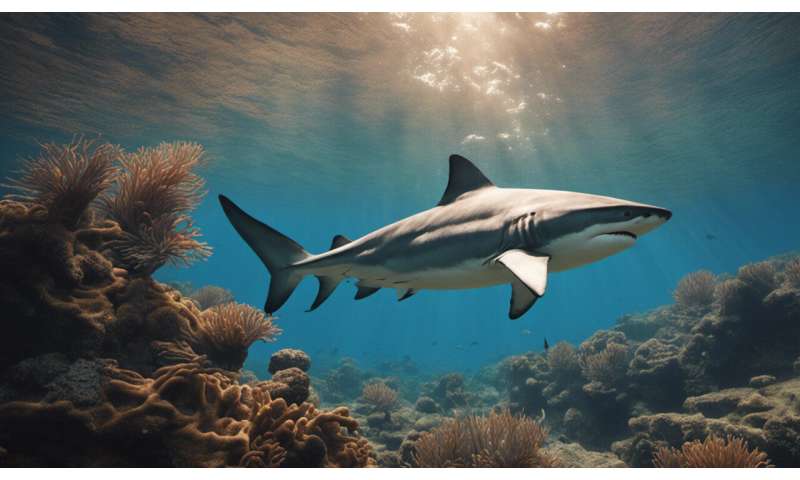

Doryteuthis pealeii, often called the Woods Hole squid. Studies with D. pealeii have led to major advances in neurobiology, including description of the fundamental mechanisms of neurotransmission. The Marine Biological Laboratory collects D. pealeii from local waters for an international community of researchers. Credit: Roger Hanlon

Doryteuthis pealeii, often called the Woods Hole squid. Studies with D. pealeii have led to major advances in neurobiology, including description of the fundamental mechanisms of neurotransmission. The Marine Biological Laboratory collects D. pealeii from local waters for an international community of researchers. Credit: Roger Hanlon

It is also a necessary step toward having the capacity to knock in genes that facilitate research, such as genes that encode fluorescent proteins that can be imaged to track neural activity or other dynamic processes.

"CRISPR-Cas9 worked really well in Doryteuthis; it was surprisingly efficient," Rosenthal says. Much more challenging was delivering the CRISPR-Cas system into the one-celled squid embryo, which is surrounded by an exceedingly tough outer layer, and then raising the embryo through hatching. The team developed micro-scissors to clip the egg's surface and a beveled quartz needle to deliver the CRISPR-Cas9 reagents through the clip.

Studies with Doryteuthis pealeii have led to foundational advances in neurobiology, beginning with description of the action potential (nerve impulse) in the 1950s, a discovery for which Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley became Nobel Prize laureates in 1963. For decades D. pealeii has drawn neurobiologists from all over the world to the MBL, which collects the squid from local waters.

Recently, Rosenthal and colleagues discovered extensive recoding of mRNA in the nervous system of Doryteuthis and other cephalopods. This research is under development for potential biomedical applications, such as pain management therapy.

D. pealeii is not, however, an ideal species to develop as a genetic research organism. It's big and takes up a lot of tank space plus, more importantly, no one has been able to culture it through multiple generations in the lab.

For these reasons, the MBL Cephalopod Program's next goal is to transfer the new knockout technology to a smaller cephalopod species, Euprymna berryi (the hummingbird bobtail squid), which is relatively easy to culture to make genetic strains.

Explore furtherThe mysterious, legendary giant squid's genome is revealed

More information: Current Biology (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.099

Journal information: Current Biology

Provided by Marine Biological Laboratory

A team at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) has achieved the first gene knockout in a cephalopod using the squid Doryteuthis pealeii, an exceptionally important research organism in biology for nearly a century. The milestone study, led by MBL Senior Scientist Joshua Rosenthal and MBL Whitman Scientist Karen Crawford, is reported in the July 30 issue of Current Biology.

The team used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to knock out a pigmentation gene in squid embryos, which eliminated pigmentation in the eye and in skin cells (chromatophores) with high efficiency.

"This is a critical first step toward the ability to knock out—and knock in—genes in cephalopods to address a host of biological questions," Rosenthal says.

Cephalopods (squid, octopus and cuttlefish) have the largest brain of all invertebrates, a distributed nervous system capable of instantaneous camouflage and sophisticated behaviors, a unique body plan, and the ability to extensively recode their own genetic information within messenger RNA, along with other distinctive features. These open many avenues for study and have applications in a wide range of fields, from evolution and development, to medicine, robotics, materials science, and artificial intelligence.

The ability to knock out a gene to test its function is an important step in developing cephalopods as genetically tractable organisms for biological research, augmenting the handful of species that currently dominate genetic studies, such as fruit flies, zebrafish, and mice.

Doryteuthis pealeii, often called the Woods Hole squid. Studies with D. pealeii have led to major advances in neurobiology, including description of the fundamental mechanisms of neurotransmission. The Marine Biological Laboratory collects D. pealeii from local waters for an international community of researchers. Credit: Roger Hanlon

Doryteuthis pealeii, often called the Woods Hole squid. Studies with D. pealeii have led to major advances in neurobiology, including description of the fundamental mechanisms of neurotransmission. The Marine Biological Laboratory collects D. pealeii from local waters for an international community of researchers. Credit: Roger HanlonIt is also a necessary step toward having the capacity to knock in genes that facilitate research, such as genes that encode fluorescent proteins that can be imaged to track neural activity or other dynamic processes.

"CRISPR-Cas9 worked really well in Doryteuthis; it was surprisingly efficient," Rosenthal says. Much more challenging was delivering the CRISPR-Cas system into the one-celled squid embryo, which is surrounded by an exceedingly tough outer layer, and then raising the embryo through hatching. The team developed micro-scissors to clip the egg's surface and a beveled quartz needle to deliver the CRISPR-Cas9 reagents through the clip.

Studies with Doryteuthis pealeii have led to foundational advances in neurobiology, beginning with description of the action potential (nerve impulse) in the 1950s, a discovery for which Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley became Nobel Prize laureates in 1963. For decades D. pealeii has drawn neurobiologists from all over the world to the MBL, which collects the squid from local waters.

Recently, Rosenthal and colleagues discovered extensive recoding of mRNA in the nervous system of Doryteuthis and other cephalopods. This research is under development for potential biomedical applications, such as pain management therapy.

D. pealeii is not, however, an ideal species to develop as a genetic research organism. It's big and takes up a lot of tank space plus, more importantly, no one has been able to culture it through multiple generations in the lab.

For these reasons, the MBL Cephalopod Program's next goal is to transfer the new knockout technology to a smaller cephalopod species, Euprymna berryi (the hummingbird bobtail squid), which is relatively easy to culture to make genetic strains.

Explore furtherThe mysterious, legendary giant squid's genome is revealed

More information: Current Biology (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.099

Journal information: Current Biology

Provided by Marine Biological Laboratory

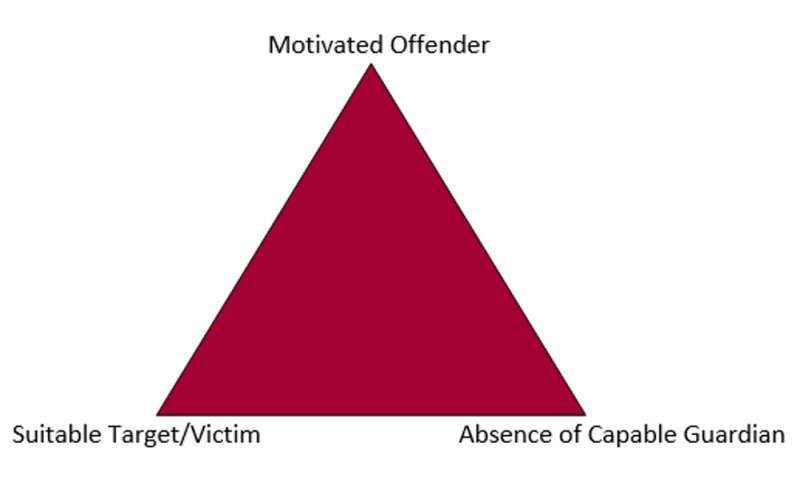

Routine activity theory (or the crime triangle). Credit: UN Office on Drugs and Crime

Routine activity theory (or the crime triangle). Credit: UN Office on Drugs and Crime