The Long Walk of the Situationist International

“The situationists were bent on discovering the absolute ability to criticize anyone, anywhere — without restraint, without the pull of alliances, and without self-satisfaction. And they were bent on turning that criticism into event.”

by GREIL MARCUS

MARCH 18, 2020

The Long Walk of the Situationist International: How Extreme Was It

VLS, October 11, 1982

— 1 —

I first became intrigued with the Situationist International in 1979, when I struggled through “Le Bruit et la Fureur,” one of the anonymous lead articles in the first issue of the journal Internationale Situationniste. The writer reviewed the exploits of artistic rebels in the postwar West as if such matters had real political consequences, and then said this: “The rotten egg smell exuded by the idea of God envelops the mystical cretins of the American ‘Beat Generation,’ and is not even entirely absent from the declarations of the Angry Young Men… They have simply come to change their opinions about a few social conventions without even noticing the whole change of terrain of all cultural activity so evident in every avant-garde tendency of this century. The Angry Young Men are in fact particularly reactionary in their attribution of a privileged, redemptive value to the practice of literature: they are defending a mystification that was denounced in Europe around 1920 and whose survival today is of greater counterrevolutionary significance than that of the British Crown.”

Mystical cretins… finally, I thought (forgetting the date of the publication before me), someone has cut through the suburban cul-de-sac that passed for cultural rebellion in the 1950s. But this wasn’t “finally” — it was 1958, in a sober, carefully printed magazine (oddly illustrated with captionless photos of women in bathing suits), in an article that concluded: “If we are not surrealists it is because we don’t want to be bored… Decrepit surrealism, raging and ill-informed youth, well-off adolescent rebels lacking perspective but far from lacking a cause — boredom is what they all have in common. The situationists will execute the judgment contemporary leisure is pronouncing against itself.”

RELATED

FROM THE ARCHIVES

Last Refuge of a Rock Critic: A Bicentennial Search for Patriotism

by GREIL MARCUS

Strange stuff — almost mystifying for an American — but there was a power in the prose that was even more seductive than the hard-nosed dismissal of the Beat generation. This was the situationist style — what one commentator called “a rather irritating form of hermetic terrorism,” a judgment situationist Raoul Vaneigem would quote with approval. Over the next decade it never really changed, but only became more seductive and more hard-nosed, because it discovered more seductive and hard-nosed opponents. Beginning with the notion that modern life was boring and therefore wrong, the situationists sought out every manifestation of alienation and domination and every manifestation of the opposition produced by alienation and domination. They turned out original analyses of the former (whether it was the Kennedy-era fallout shelter program in “The Geopolitics of Hibernation” — what a title! — or the Chinese cultural revolution in “The Explosion Point of Ideology in China”) and mercilessly criticized the timidity and limits of the latter. In every case they tried to link specifics to a totality — why was the world struggling to turn itself inside out, and how could it be made to do so? What were the real sources of revolution in postwar society, and how were they different from any that had come before?

The Situationist International Anthology contains pre-SI documents, 250 pages of material from the situationist journal, May 1968 documents, two filmscripts, and far more, stretching from 1953, four years before the Situationist International was formed, to 1971, a year before its formal dissolution. It is exhilarating to read this book — to confront a group that was determined to make enemies, burn bridges, deny itself the rewards of celebrity, to find and maintain its own voice in a world where, it seemed, all other voices of cultural or political resistance were either cravenly compromised or so lacking in consciousness they did not even recognize their compromises.

— 2 —

The attack on the Beat Generation and the Angry Young Men — in 1958, it is worth remembering, considered in the English-speaking world the very summa of “anti-Establishment” negation — was an opening round in a struggle the situationists thought was already going on, and a move toward a situation they meant to construct. “Our ideas are in everyone’s mind,” they would say more than once over the next 10 years. They meant that their ideas for a different world were in everyone’s mind as desires, but not yet as ideas. Their project was to expose the emptiness of everyday life in the modern world and to make the link between desire and idea real. They meant to make that link so real it would be acted upon by almost everyone, since in the modern world, in the affluent capitalist West and the bureaucratic state-capitalist East, the split between desire and idea was part of almost everyone’s life.

Throughout the next decade, the situationists argued that the alienation which in the 19th century was rooted in production had, in the 20th century, become rooted in consumption. Consumption had come to define happiness and to suppress all other possibilities of freedom and selfhood. Lenin had written that under communism everyone would become an employee of the state; that was no less capitalism than the Western version, in which everyone was first and foremost a member of an economy based in commodities. The cutting edge of the present-day contradiction — that place where the way of life almost everyone took for granted grated most harshly against what life promised and what it delivered — was as much leisure as work. This meant the concepts behind “culture” were as much at stake as the ideas behind industry.

RELATED

MUSIC

Robert Johnson: The Sound and the Fury

by GREIL MARCUS

Culture, the situationists thought, was “the Northwest Passage” to a superseding of the dominant society. This was where they started; this was the significance of their attack on the Beat generation. It was a means to a far more powerful attack on the nature of modern society itself: on the division of labor, the fragmentation of work and thought, the manner in which the material success of modern life had leaped over all questions of the quality of life, in which “the struggle against poverty… [had] overshot its ultimate goal, the liberation of man from material cares,” and produced a world in which, “faced with the alternative of love or a garbage disposal unit, young people of all countries have chosen the garbage disposal unit.”

I have presented a bare outline of the situationist perspective, but perhaps more important for a reader in 1982 is the use the situationists made of that perspective. Unlike many with whom they shared certain notions — Norman Mailer, the Marxist sociologist Henri Lefebvre, the gauchiste review Socialisme ou Barbarie — the situationists were bent on discovering the absolute ability to criticize anyone, anywhere — without restraint, without the pull of alliances, and without self-satisfaction. And they were bent on turning that criticism into events.

— 3 —

The situationists thought of themselves as avant-garde revolutionaries, linked as clearly to dada as to Marx. One could trace them back to Saint-Just — the 22-year-old who arrived in Paris in 1789 with a blasphemous epic poem, Organt (an account of the raping of nuns and of endless sexual adventures), and became the coldest, most romantic, most brilliant, most tragic administrator of the Terror. Prosecutor of Louis XVI, he gave his head to the same guillotine a year later.

More directly, situationist thinking began in Paris in the early 1950s, when Guy Debord and a few other members of the Lettrist International — a group, known mostly to itself, which had split off from the Lettrists, a tiny, postwar neodada movement of anti-art intellectuals and students — devoted themselves to dérives: to drifting through the city for days, weeks, even months at a time, looking for what they called the city’s psychogeography. They meant to find signs of what lettrist Ivan Chtcheglov called “forgotten desires” — images of play, eccentricity, secret rebellion, creativity, and negation. That led them into the Paris catacombs, where they sometimes spent the night. They looked for images of refusal, or for images society had itself refused, hidden, suppressed, or “recuperated” — images of refusal, nihilism, or freedom that society had taken back into itself, co-opted or rehabilitated, isolated or discredited. Rooted in similar but intellectually (and physically!) far more limited surrealist expeditions of the 1920s, the dérives were a search, Guy Debord would write many years later, for the “supersession of art.” They were an attempt to fashion a new version of daily life — a new version of how people organized their wishes, pains, fears, hopes, ambitions, limits, social relationships, and identities, a process that ordinarily took place without consciousness.

RELATED

MUSIC

Patti Smith Exposes Herself

by GREIL MARCUS

The few members of the grandiosely named Lettrist International wanted to reshape daily life according to the desires discovered and affirmed by modern art. Dada, at the Cabaret Voltaire “a laboratory for the rehabilitation of everyday life” in which art as art was denounced and scattered, “wanted to suppress art without realizing it,” Debord wrote in 1967, in his book The Society of the Spectacle. “Surrealism wanted to realize art without suppressing it.” In other words, dada wanted to kill off the claim that art was superior to life and leave art for dead. Surrealism wanted to turn the impulses that led one to create art into a recreation of life, but it also wanted to maintain the production of art works. Thus surrealism ended up as just another debilitated, gallery-bound art movement, a fate dada avoided at the price of being almost completely ignored. The Lettrist International thought art had to be both suppressed as separate, special activity, and turned into life. That was the meaning of supersession, and that was the meaning of a group giving itself up to the pull of the city. It was also the meaning of the LI’s attack on art as art. Debord produced a film without images; with the Danish painter Asger Jorn, he created a book “ ‘composed entirely of prefabricated elements,’ in which the writing on each page runs in all directions and the reciprocal relations of the phrases are invariably uncompleted.” Not only was the book impossible to “read,” it featured a sandpaper jacket, so that when placed in a bookshelf it would eat other books.

In 1952, at the Ritz, the LI broke up a Charlie Chaplin press conference, part of the huge publicity campaign for Limelight. “We believe that the most urgent expression of freedom is the destruction of idols, especially when they present themselves in the name of freedom,” they explained. “The provocative tone of our leaflet was an attack against a unanimous, servile enthusiasm.” (Provocative was perhaps not the word. “No More Flat Feet,” the leaflet Debord and others scattered in the Ritz, read: “Because you [Chaplin] identified yourself with the weak and the oppressed, to attack you was to strike the weak and the oppressed, but in the shadow of your rattan cane some could already discern the policeman’s nightstick…”) The lettrist radicals practiced graffiti on the walls of Paris (one of their favorite mottoes, “Never work!,” would show up 15 years later during May 1968, and 13 years after that in Bow Wow Wow’s “W.O.R.K.,” written by Malcolm McLaren). They painted slogans on their ties, shoes, and pants, hoping to walk the streets as living examples of détournement — the diversion of an element of culture or everyday life (in this case, simply clothes) to a new and displacing purpose. The band “lived on the margins of the economy. It tended toward a role of pure consumption” — not of commodities, but “of time.”

From On the Passage of a Few Persons Through a Rather Brief Period of Time, Debord’s 1959 film on the group:

Voice 1: That which was directly lived reappears frozen in the distance, fit into the tastes and illusions of an era carried away with it.

Voice 2: The appearance of events we have not made, that others have made against us, obliges us from now on to be aware of the passage of time, its results, the transformation of our own desires into events. What differentiates the past from the present is precisely its out-of-reach objectivity; there is no more should-be; being is so consumed that it has ceased to exist. The details are already lost in the dust of time. Who was afraid of life, afraid of the night, afraid of being taken, afraid of being kept?

Voice 3: That which should be abolished continues, and we continue to wear away with it. Once again the fatigue of so many nights passed in the same way. It is a walk that has lasted a long time.

Voice 1: Really hard to drink more.

This was the search for that Northwest Passage, that unmarked alleyway from the world as it appeared to the world as it had never been, but which the art of the 20th century had promised it could be: a promise shaped in countless images of freedom to experiment with life and of freedom from the banality and tyranny of bourgeois order and bureaucratic rule. Debord and the others tried to practice, he said, “a systematic questioning of all the diversions and works of a society, a total critique of its idea of happiness.” “Our movement was not a literary school, a revitalization of expression, a modernism,” a Lettrist International publication stated in 1955, after some years of the pure consumption of time, various manifestos, numerous jail sentences for drug possession and drunk driving, suicide attempts, and all-night arguments. “We have the advantage of no longer expecting anything from known activities, known individuals, and known institutions.”

They tried to practice a radical deconditioning: to demystify their environment and the expectations they had brought to it, to escape the possibility that they would themselves recuperate their own gestures of refusal. The formation of the Situationist International — at first, in 1957, including 15 or 20 painters, writers, and architects from England, France, Algeria, Denmark, Holland, Italy, and Germany — was based on the recognition that such a project, no matter bow poorly defined or mysterious, was either a revolutionary project or it was nothing. It was a recognition that the experiments of the dérives, the attempts to discover lost intimations of real life behind the perfectly composed face of modern society, had to be transformed into a general contestation of that society, or else dissolve in bohemian solipsism.

RELATED

FILM

Robert Frank and the Stones Movie You’ll Never See

by GREIL MARCUS

— 4 —

Born in Paris in 1931, Guy Debord was from beginning to end at the center of the Situationist International, and the editor of its journal. The Society of the Spectacle, the concise and remarkably cant-free (or cant-destroying, for that seems to be its effect) book of theory he published after 10 years of situationist activity, begins with these lines: “In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was lived has moved away into a representation.” Determined to destroy the claims of 20th-century social organization, Debord was echoing the first sentence of Capital: “The wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails appears as an ‘immense collection of commodities.’ ” To complain, as French Marxist critics did, that Debord misses Marx’s qualification, “appears as,” is to miss Debord’s own apparent qualification, “presents itself as” — and to miss the point of situationist writing altogether. Debord’s qualification turned out not to be a qualification at all, but rather the basis of a theory in which a society organized as appearance can be disrupted on the field of appearance.

Debord argued that the commodity — now transmuted into “spectacle,” or seemingly natural, autonomous images communicated as the facts of life — had taken over the social function once fulfilled by religion and myth, and that appearances were now inseparable from the essential processes of alienation and domination in modern society. In 1651, the cover of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan presented the manifestation of a nascent bourgeois domination: a picture of a gigantic sovereign being, whose body — the body politic — was made up of countless faceless citizens. This was presented as an entirely positive image, as a utopia. In 1967, International Situationniste #11 printed an almost identical image, “Portrait of Alienation”: countless Chinese performing a card trick which produced the gigantic face of Mao Zedong.

If society is organized around consumption, one participates in social life as a consumer; the spectacle produces spectators, and thus protects itself from questioning. It induces passivity rather than action, contemplation rather than thinking, and a degradation of life into materialism. It is no matter that in advanced societies, material survival is not at issue (except for those who are kept poor in order to represent poverty and reassure the rest of the population that they should be satisfied). The “standard of survival,” like its twin, the “standard of boredom,” is raised but the nature of the standard does not change. Desires are degraded or displaced into needs and maintained as needs. A project precisely the opposite of that of modern art, from Lautréamont and Rimbaud to dada and surrealism, is

The spectacle is not merely advertising, or propaganda, or television. It is a world. The spectacle as we experience it, but fail to perceive it, “is not a collection of images, but a social relationship between people, mediated by images.” In 1928 in One-Way Street, writing about German inflation, Walter Benjamin anticipated the argument: “The freedom of conversation is being lost. If it was earlier a matter of course to take interest in one’s partner, this is now replaced by inquiry into the price of his shoes or his umbrella. Irresistibly intruding upon any convivial exchange is the theme of the conditions of life, of money. What this theme involves is not so much the concerns and sorrows of individuals, in which they might be able to help one another, as the overall picture. It is as if one were trapped in a theater and had to follow the events on the stage whether one wanted to or not, had to make them again and again, willingly or unwillingly, the subject of one’s thought and speech.” Raoul Vaneigem defined the terrain of values such a situation produced: “Rozanov’s definition of nihilism is the best: ‘The show is over. The audience get up to leave their seats. Time to collect their coats and go home. They turn around… No more coats and no more home.’ ” “The spectator feels at home nowhere,” Debord wrote, “because the spectacle is everywhere.”

The spectacle is “the diplomatic representation of hierarchic society to itself, where all other expression is banned” — which is to say where all other expression makes no sense, appears as babble (this may be the ironic, protesting meaning of dada phonetic poems, in which words were reduced to sounds, and of lettrist poetry, in which sounds were reduced to letters). The spectacle says “nothing more than ‘that which appears is good, that which is good appears.’ ” (In a crisis, or when the “standard of survival” falls, as in our own day, hierarchic society retreats, but maintains its hegemony, the closing of questions. The spectacle “no longer promises anything,” Debord wrote in 1979, in a new preface to the fourth Italian edition of his book. “It simply says, ‘It is so.’ ”) The spectacle organizes ordinary life (consider the following in terms of making love): “The alienation of the spectator to the profit of the contemplated object is expressed in the following way: the more he contemplates the less he lives; the more he accepts recognizing himself in the dominant images of need, the less he understands his own existence and his own desires. The externality of the spectacle in relation to the active man appears in the fact that his own gestures are no longer his but those of another who represents them to him.”

Debord summed it up this way: “The first phase of the domination of the economy over social life brought into the definition of all human realization the obvious degradation of being into having. The present phase of total occupation of social life by the accumulated results of the economy” — by spectacle — “leads to a generalized sliding of having into appearing.” We are twice removed from where we want to be, the situationists argued — yet each day still seems like a natural fact.

— 5 —

This was the situationists’ account of what they, and everyone else, were up against. It was an argument from Marx’s 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, an argument that the “spectacle-commodity society,” within which one could make only meaningless choices and against which one could seemingly not intervene, had succeeded in producing fundamental contradictions between what people accepted and what, in ways they could not understand, they wanted.

This was the precise opposite of social science, developed at precisely the time when the ideology of the end of ideology was conquering the universities of the West. It was an argument about consciousness and false consciousness, not as the primary cause of domination but as its primary battleground.

If capitalism had shifted the terms of its organization from production to consumption, and its means of control from economic misery to false consciousness, then the task of would-be revolutionaries was to bring about a recognition of the life already lived by almost everyone. Foreclosing the construction of one’s own life, advanced capitalism had made almost everyone a member of a new proletariat, and thus a potential revolutionary. Here again, the discovery of the source of revolution in what “modern art [had] sought and promise” served as the axis of the argument. Modern art, one could read in Internationale Situationniste #8, in January of 1963, had “made a clean sweep of all the values and rules of everyday behavior,” of unquestioned order and the “unanimous, servile enthusiasm” Debord and his friends had thrown up at Chaplin; but that clean sweep had been isolated in museums. Modern revolutionary impulses had been separated from the world, but “just as in the nineteenth century revolutionary theory arose out of philosophy” — out of Marx’s dictum that philosophy, having interpreted the world, must set about changing it — now one had to look to the demands of art.

At the time of the Paris Commune in 1871, workers discussed matters that had previously been the exclusive province of philosophers — suggesting the possibility that philosophy could be realized in daily life. In the 20th century, with “survival” conquered as fact but maintained as ideology, the same logic meant that just as artists constructed a version of life in words, paint, or stone, men and women could themselves begin to construct their own lives out of desire. This desire, in scattered and barely noticed ways, was shaping the 20th century, or the superseding of it (“Ours is the best effort so far toward getting out of the twentieth century,” an anonymous situationist wrote in 1963, in one of the most striking lines in the 12 issues of Internationale Situationniste). It was the desire more hidden, more overwhelmed and confused by spectacle, than any other. It had shaped the lettrist adventures. It was the Northwest Passage. If the spectacle was “both the result and the project of the existing mode of production,” then the construction of life as artists constructed art — in terms of what one made of friendship, love, sex, work, play, and suffering — was understood by the situationists as both the result and the project of revolution.

— 6 —

To pursue this revolution, it was necessary to take all the partial and isolated incidents of resistance and refusal of things as they were, and then link them. It was necessary to discover and speak the language of these incidents, to do for signs of life what the Lettrist International had tried to do for the city’s signs of “forgotten desires.” This demanded a theory of exemplary acts. Society was organized as appearance, and could be contested on the field of appearance; what mattered was the puncturing of appearance — speech and action against the spectacle that was, suddenly, not babble, but understood. The situationist project, in this sense, was a quest for a new language of action. That quest resulted in the urgent, daring tone of even the lengthiest, most solemn essays in Internationale Situationniste — the sense of minds engaged, quickened beyond rhetoric, by emerging social contradictions — and it resulted in such outrages as a six-word analysis of a leading French sociologist. (“M. GEORGES LAPASSADE,” announced almost a full page of I.S. #9, “EST UN CON.”) It led as well to a style of absurdity and play, and to an affirmation that contestation was fun: a good way to live. The situationists delighted in the discovery that dialectics caused society to produce not just contradictions but also endless self parodies. Their journal was filled with them — my favorite is a reproduction of an ad for the Peace o’ Mind Fallout Shelter Company. And the comics that illustrated I.S. led to détournement of the putative heroes of everyday life. Characters out of Steve Canyon and True Romance were given new balloons, and made to speak passionately of revolution, alienation, and the lie of culture — as if even the most unlikely people actually cared about such things. In the pages of I.S., a kiss suggested not marriage but fantasies of liberation: a sigh for the Paris Commune.

The theory of exemplary acts and the quest for a new language of action also brought the situationists’ pursuit of extremism into play. I.S #10, March 1966, on the Watts riots: “…all those who went so far as to recognize the ‘apparent justifications’ of the rage of the Los Angeles blacks… all those ‘theorists’ and ‘spokesmen’ of international Left, or rather of its nothingness, deplored the irresponsibility, the disorder, the looting (especially the fact that arms and alcohol were the first targets for plunder)… But who has defended the rioters of Los Angeles in the terms they deserve? We will.” The article continued: “The looting of the Watts district was the most direct realization of the distorted principle, ‘To each according to his false needs’… [but] real desires begin to be expressed in festival, in the potlatch of destruction… For the first time it is not poverty but material abundance which must be dominated [and of course it was the relative “affluence” of the Watts rioters, at least as compared to black Americans in Harlem, that so mystified the observers of this first outbreak of violent black rage]… Comfort will never be comfortable enough for those who seek what is not on the market.”

“The task of being more extremist than the SI falls to the SI itself,” the situationists said; that was the basis of the group’s continuation. The situationists looked for exemplary acts which might reveal to spectators that that was all they were. They cited, celebrated, and analyzed incidents which dramatized the contradictions of modern society, and contained suggestions of what forms a real contestation of that society might take. Such acts included the Watts riots; the resistance of students and workers to the Chinese cultural revolution (a struggle, the situationists wrote, of “the official owners of the ideology against the majority of the owners of the apparatus of the economy and the state”); the burning of the Koran in the streets of Baghdad in 1959; the exposure of a site meant to house part of the British government in the event of nuclear war; the “kidnapping” of art works by Caracas students, who used them to demand the release of political prisoners; the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley in 1964; the situationist-inspired disruption of classes taught by French cyberneticians in 1966 at Strasbourg, and by sociologists at Nanterre in 1967 and 1968; and the subversion of Berlin actor Wolfgang Neuss, who in 1963 “perpetrated a most suggestive act of sabotage… by placing a notice in the paper Der Abend giving away the identity of the killer in a television serial that had been keeping the masses in suspense for weeks.”

Some of these actions led nowhere; some, like the assaults on the cyberneticians and sociologists, led to May 1968, where the idea of general contestation on the plane of appearances was realized.

The situationist idea was to prevent the recuperation of such incidents by making theory out of them. Once the speech of the spectacle no longer held a monopoly, it would be heard as babble — as mystification exposed. Those who took part in wildcat strikes or practiced cultural sabotage, the situationists argued, acted out of boredom, rage, disgust — out of an inchoate but inescapable perception that they were not free and, worse, could not form a real image of freedom. Yet there were tentative images of freedom being shaped, which, if made into theory, could allow people to understand and maintain their own actions. Out of this, a real image of freedom would appear, and it would dominate: the state and society would begin to dissolve. Resistance to that dissolution would be stillborn, because workers, soldiers, and bureaucrats would act on new possibilities of freedom no less than anyone else — they would join in a general wildcat strike that would end only when society was reconstructed on new terms. When the theory matched the pieces of practice from which the theory was derived, the world would change.

RELATED

MUSIC

Bob Dylan: Positively Main Street

by TOBY THOMPSON

— 7 —

The situationist program — as opposed to the situationist project, the situationist practice — came down to Lautréamont and workers’ councils. On one side, the avant-garde saint of negation, who had written that poetry “must be made by all”; on the other, the self-starting, self-managing organs of direct democracy that had appeared in almost every revolutionary moment of the 20th century, bypassing the state and allowing for complete participation (the soviets of Petrograd in 1905 and 1917, the German Räte of 1919, the anarchist collectives of Barcelona in 1936, the Hungarian councils of 1956). Between those poles, the situationists thought, one would find the liberation of everyday life, the part of experience that was omitted from the history books.

These were the situationist touchstones — and, oddly, they were left unexamined. The situationists’ use of workers’ councils reminds me of those moments in D.W. Griffith’s Abraham Lincoln when, stumped by how to get out of a scene, he simply had Walter Huston gaze heavenward and utter the magic words, “The Union!” It is true that the direct democracy of workers’ councils — where anyone was allowed to speak, where representation was kept to a minimum and delegates were recallable at any moment — was anathema both to the Bolsheviks and to the Right. It may also have been only the crisis of a revolutionary situation that produced the energy necessary to sustain council politics. The situationists wrote that no one had tried to find out how people had actually lived during those brief moments when revolutionary contestation had found its form — a form that would shape the new society — but they did not try either. They spoke endlessly about “everyday life,” but ignored work that examined it both politically and in its smallest details (James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Foucault’s Madness and Civilization, the books of the Annale school, Walter Benjamin’s One-Way Street and A Berlin Chronicle, the writing of Larissa Reissner, a Pravda correspondent who covered Weimar Germany), and produced nothing to match it.

But if Lautréamont, workers’ councils, and everyday life were more signposts than true elements of a theory, they worked as signposts. The very distance of such images from the world as it was conventionally understood helped expose what that the world concealed. What appeared between the signposts of Lautréamont and workers’ councils was the possibility of critique.

RELATED

MUSIC

A Sid Vicious Story

by LESTER BANGS

Pursued without compromise or self-censorship, that critique liberated the situationists from the reassurances of ideology as surely as the experiments of the Lettrist International had liberated its members from the seductions of the bourgeois art world. It opened up a space of freedom, and was a necessary preface to the new language of action the situationists were after. A single example will do: the situationist analysis of Vietnam, published in I.S. #11 in March 1967 — almost frightening in its prescience, and perhaps even more frightening in its clarity.

“It is obviously impossible to seek, at the moment, a revolutionary solution to the Vietnam war,” said the anonymous writer. “It is first of all necessary to put an end to the American aggression in order to allow the real social struggle in Vietnam to develop in a natural way; that is to say, to allow the Vietnamese workers and peasants to rediscover their enemies at home; the bureaucracy of the North and all the propertied and ruling strata of the South. The withdrawal of the Americans will mean that the Stalinist bureaucracy will immediately seize control of the whole country: this is the unavoidable conclusion. Because the invaders cannot indefinitely sustain their aggression; ever since Talleyrand it has been a commonplace that one can do anything with a bayonet except sit on it. The point, therefore, is not to give unconditional (or even conditional) support to the Vietcong, but to struggle consistently and without any concessions against American imperialism… The Vietnam war is rooted in America and it is from there that it must be rooted out.” This was a long way from the situationists’ rejection of the Beat generation, but the road had been a straight one.

If the situationists were fooled, it was only by themselves; they were not fooled by the world. They understood, as no one else of their time did, why major events — May 1968, the Free Speech Movement, or, for that matter, Malcolm McLaren’s experiment with what Simon Frith has called the politicization of consumption — arise out of what are, seemingly, the most trivial provocations and the most banal repressions. They understood why the smallest incidents can lead, with astonishing speed, to a reopening of all questions. Specific, localized explanations tied to economic crises and political contexts never work, because the reason such events developed as they did was what the situationists said it was: people were bored, they were not free, they did not know how to say so. Given the chance, they would say so. People could not form a real image of freedom, and they would seize any opportunity that made the construction of such an image possible.

RELATED

Punk ’77: A Cult Explodes, and a Movement Is Born

by ROBERT CHRISTGAU

— 8 —

Leaving the 20th Century, edited and translated by former British situationist Christopher Gray, published only in the UK and long out of print, was until Ken Knabb’s book the best representation of situationist writing in English, and it was not good. Translations were messy and inaccurate, the selection of articles erratic and confusing, the commentary often mushy.

With the exception of a good edition of The Society of the Spectacle put out by Black & Red of Detroit in 1977, other situationist work in English was far worse. A few pieces — “The Decline and Fall of the Spectacle-Commodity Society” (on Watts), “On the Poverty of Student Life” (the SI’s most famous publication, which caused a scandal in France in 1966 and prefigured the May 1968 revolt), “The Beginning of an Era” (on May 1968) — appeared as smudgy, sometimes gruesomely typeset and translated pamphlets. Most were put out by the short-lived British or American sections of the SI, or by small situationist-inspired groups in New York or Berkeley.

The situationist journal, and the situationist books as they were originally published in Paris, could not have been more different. Wonderfully illustrated with photos, comics, reproductions of advertisements, drawings, and maps, Internationale Situationniste had an elegant, straightforward design: flat, cool, and direct. It made a simple point: what we have written is meant seriously and should be read seriously.

The Situationist International Anthology does not present the complete text of the situationist journal, and it has no illustrations. But the translations are clear and readable — sometimes too literal, sometimes inspired. Entirely self-published, the anthology is a better job of book-making than most of the books published today by commercial houses. There are virtually no typos; it is well indexed, briefly but usefully annotated, and the design, binding, and printing are all first class.

In other words, Knabb has, unlike most other publishers of situationist material in English, taken the material seriously, and allowed it to speak with something like its original authority. One can follow the development of a group of writers which devoted itself to living up to one of its original prescriptions: “The task of an avant-garde is to keep abreast of reality.”

The situationist journal was never copyrighted. Rather, it bore this legend: “All the texts published in International Situationniste may be freely reproduced, translated, or adapted, even without indication of origin.” Knabb’s book carries an equivalent notation.

RELATED

THE CULTURE

William S. Burroughs Talks With Tennessee Williams

by THE VILLAGE VOICE ARCHIVES

— 9 —

The role of the Situationist International, its members wrote, was not to act as any sort of vanguard party. The situationists “had to know how to wait,” and to be ready to disappear in a common festival of revolt. Their job was not to “build” the SI, as the job of a Trotskyist or Bolshevik militant is to build his or her organization, trimming all thoughts and all pronouncements to that goal, careful not to offend anyone who might be seduced or recruited. Their job was to think and speak as clearly as possible — not to get people to listen to speeches, they said, but to get people to think for themselves.

Rather than expanding their group, the situationists worked to make it smaller, expelling careerist, backsliding, or art-as-politics (as opposed to politics-as-art) members almost from the day the group was formed. By the time of the May 1968 revolt, the Situationist International was composed mostly of Parisians hardly more numerous — perhaps less numerous — than those who walked the streets as the Lettrist International. Behind them they had 11 numbers of their journal, more than a decade of fitting theory to fragments of practice, and the scandals of Strasbourg and Nanterre, both of which gained them a far wider audience than they had ever had before. And so, in May, they made a difference. They defined the mood and the spirit of the event: almost all of the most memorable graffiti from that explosion came, as inspiration or simply quotation, from situationist books and essays. “Those who talk about revolution and class struggle, without understanding what is subversive about love and positive in the refusal of constraints,” ran one apparently spontaneous slogan, in fact a quote from Raoul Vaneigem, “such people have corpses in their mouths.”

At the liberated Sorbonne and later in their own Council for Maintaining the Occupations, the situationists struggled against reformism, working to define the most radical possibilities of the May revolt — “[This] is now a revolutionary movement,” read their “Address to All Workers” of May 30, 1968, “a movement which lacks nothing but the consciousness of what it has already done in order to triumph” — which meant, in the end, that the situationists would leave behind the most radical definition of the failure of that revolt. It was an event the situationists had constructed, in the pages of their journal, long before it took place. One can look back to January 1963 and read in I.S. #8: “We will only organize the detonation.”

RELATED

SPORTS

Ishmael Reed on Muhammad Ali

by ISHMAEL REED

— 10 —

What to make of this strange mix of post-surrealist ideas about art, Marxian concepts of alienation, an attempt to recover a forgotten revolutionary tradition, millenarianism, and plain refusal of the world combined with a desire to smash it? Nothing, perhaps. The Situationist International cannot even be justified by piggy-backing it onto official history, onto May 1968, not because that revolt failed, but because it disappeared. If 300 books on May 1968 were published within a year of the event, as I.S. #12 trumpeted, how many were published in the years to follow? If the situationist idea of general contestation was realized in May 1968, the idea also realized its limits. The theory of the exemplary act — and May was one great, complex, momentarily controlling exemplary act — may have gone as far as such a theory or such an act can go.

What one can make of the material in the Situationist International Anthology is perhaps this: out of the goals and the perspectives the situationists defined for themselves came a critique so strong it forces one to try to understand its sources and its shape, no matter how much of it one might see through. In an attack on the Situationist International published in 1978, Jean Barrot wrote that it had wound up “being used as literature.” This is undoubtedly true, and it is as well a rather bizarre dismissal of the way in which people might use literature. “An author who teaches a writer nothing,” Walter Benjamin wrote in “The Author as Producer,” “teaches nobody anything. The determining factor is the exemplary character of a production that enables it, first, to lead other producers to this production, and secondly to present them with an improved apparatus for their use. And this apparatus is better to the degree that it leads consumers to production, in short that it is capable of making co-workers out of readers or spectators.” The fact is that the writing in the Situationist International Anthology makes almost all present-day political and aesthetic thinking seem cowardly, self-protecting, careerist, and satisfied. The book is a means to the recovery of ambition.

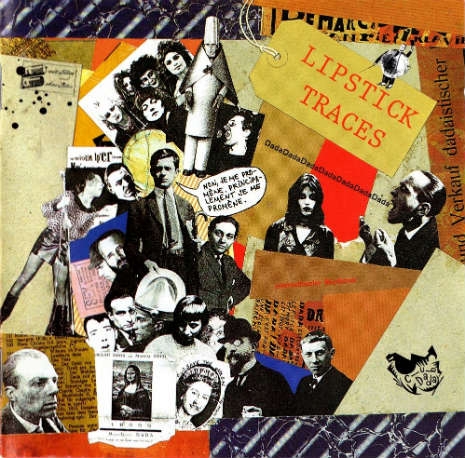

FROM HIS PHENOMENAL BOOK ON THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL,

ANARCHY AND PUNK

Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century,

Twentieth Anniversary Edition

https://www.pdfdrive.com/lipstick-traces-a-secret-history-of-the-twentieth-century-twentieth-anniversary-edition-e165956022.htm

[PDF]

GREIL MARCUS Preface from Lipstick Traces - Sites at Penn ...

https://sites.psu.edu › punk › files › 2016/05 › Marcus-Preface_to_Lipstick...

GREIL MARCUS. Preface from Lipstick Traces (1989). From inside a London tea room,

two well-dressed women look with mild disdain at a figure in the rain ...

“Creeping through time…” (1989 interview re: 'Lipstick Traces ...

https://greilmarcus.net › 2018/10/26 › creeping-through-time-1989-intervi...

Oct 26, 2018 - ... of Midnight, 1989, feat. GM discussing Lipstick Traces. ... This entry was posted in Interviews with Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces. Bookmark the .

LIPSTICK TRACES: A SECRET HISTORY OF THE 20TH CENTURY, THE SOUNDTRACK

03.15.2011

If I had to sit down and compile a list of my top favorite books—which would be difficult for me to do—there would most assuredly be a spot in the top fifty for Greil Marcus’s sprawling, idiosyncratic and essential, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century.

This book is about a single serpentine fact: late in 1976 a record called Anarchy in the U.K. was issued in London, and this event launched a transformation of pop music all over the world. Made by a four-man rock ‘n’ roll band called the Sex Pistols, and written by singer Johnny Rotten, the song distilled, in crudely poetic form, a critique of modern society once set out by a small group of Paris-based intellectuals.

Lipstick Traces, well, traces the critique of capitalism from the Dada art movement through the Situationist International and the May 1968 uprisings in Paris, through to the Sex Pistols and the punk rock explosion. In other words, it is the hidden history of the artistic opposition to capitalist society. It was heavily influenced by the revolutionary avant-garde punk zine “Vague” (a parody of Vogue, if that’s not obvious). I was reading “Vague” from my late teens—I still have most issues—and it had a great deal to do with shaping how I see the world. Marcus cribbed a lot from Tom Vague for Lipstick Traces, which is not to take anything away from Greil Marcus at all, but to simply give credit where its due.

Although I can recall a lot of criticism that was leveled at Lipstick Traces by reviewers when it first came out, the book’s thesis was, in my opinion, on pretty firm ground. It has certainly stood the test of time and has remained in print to this day. I’m told that it’s often used in college courses, which is unsurprising. A twentieth anniversary edition of Lipstick Traces was published by Harvard Press in 2009

But what many ardent admirers of the book don’t know, it that Rough Trade released a companion “soundtrack” CD to Lipstick Traces that came out in 1993. Like the book, it’s always had pride of place in my vast collection of “stuff.” The CD was rarely encountered in a world prior to Amazon.com (there’s not even a listing for it on Amazon today, either) but now, thanks to the fine folks at Ubuweb, these rare audio documents, lovingly assembled by Marcus, can be heard again. The selection runs the gamut of weird old hillbilly folk, doo-wop, to punk rock from the Slits, Buzzcocks. Gang of Four, The Adverts, Kleenex/Liliput, The Raincoats, The Mekons, a recording of the audience at a Clash gig, and best of all, the blistering mutant be-bop of Essential Logic’s “Wake Up.” Interspersed between the music is spoken word material from French philosopher Guy Debord, Triatan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck and even Marie Osmond reciting a brain-damaged version of Hugo Ball’s nonsense poem “Karawane” that must be heard to be believed.

Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century

Greil Marcus

Published 1989

Art

Greil Marcus, author of "Mystery Train", widely acclaimed as the best book ever written about America as seen through its music, began work on this new book out of a fascination with the Sex Pistols: that scandalous antimusical group, invented in London in 1975 and dead within two years, which sparked the emergence of the culture called punk. 'I am an antichrist!' shouted singer Johnny Rotten - where in the world of pop music did that come from? Looking for an answer, with a high sense of the drama of the journey, Marcus takes us down the dark paths of counterhistory, a route of blasphemy, adventure, and surprise. This is no mere search for cultural antecedents. Instead, what Marcus so brilliantly shows is that various kinds of angry, absolute demands - demands on society, art, and all the governing structures of everyday life - seem to be coded in phrases, images, and actions passed on invisibly, but inevitably, by people quite unaware of each other. Marcus lets us hear strange yet familiar voices: of such heretics as the Brethren of the Free Spirit in medieval Europe and the Ranters in seventeenth-century England; the dadaists in Zurich in 1916 and Berlin in 1918, wearing death masks, chanting glossolalia; one Michel Mourre, who in 1950 took over Easter Mass at Notre-Dame to proclaim the death of God; the Lettrist International and the Situationist International, small groups of Paris-based artists and writers surrounding Guy Debord, who produced blank-screen films, prophetic graffiti, and perhaps the most provocative social criticism of the 1950s and '60s; the rioting students and workers of May '68, scrawling cryptic slogans on city walls and bringing France to a halt; and, the Sex Pistols in London, recording the savage "Anarchy in the U.K.", and "God Save the Queen". Although the Sex Pistols shape the beginning and the end of the story, "Lipstick Traces" is not a book about music; it is about a common voice, discovered and transmitted in many forms. Working from scores of previously unexamined and untranslated essays, manifestos, and filmscripts, from old photographs, dada sound poetry, punk songs, collages, and classic texts from Marx to Henri Lefebvre, Marcus takes us deep behind the acknowledged events of our era, into a hidden tradition of moments that would seem imaginary except for the fact that they are real: a tradition of shared utopias, solitary refusals, impossible demands, and unexplained disappearances. Written with grace and force, humor and an insistent sense of tragedy and danger, "Lipstick Traces" tells a story as disruptive and compelling as the century itself.

A Review «LIPSTICK TRACES: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century» by Greil Marcus

Article (PDF Available) · April 1989

Kevin Anthony Brown

5.17

City University of New York

“Creeping through time…” (1989 interview re: 'Lipstick Traces ...

https://greilmarcus.net › 2018/10/26 › creeping-through-time-1989-intervi...

Oct 26, 2018 - ... of Midnight, 1989, feat. GM discussing Lipstick Traces. ... This entry was posted in Interviews with Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces. Bookmark the .

LIPSTICK TRACES: A SECRET HISTORY OF THE 20TH CENTURY, THE SOUNDTRACK

03.15.2011

If I had to sit down and compile a list of my top favorite books—which would be difficult for me to do—there would most assuredly be a spot in the top fifty for Greil Marcus’s sprawling, idiosyncratic and essential, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century.

This book is about a single serpentine fact: late in 1976 a record called Anarchy in the U.K. was issued in London, and this event launched a transformation of pop music all over the world. Made by a four-man rock ‘n’ roll band called the Sex Pistols, and written by singer Johnny Rotten, the song distilled, in crudely poetic form, a critique of modern society once set out by a small group of Paris-based intellectuals.

Lipstick Traces, well, traces the critique of capitalism from the Dada art movement through the Situationist International and the May 1968 uprisings in Paris, through to the Sex Pistols and the punk rock explosion. In other words, it is the hidden history of the artistic opposition to capitalist society. It was heavily influenced by the revolutionary avant-garde punk zine “Vague” (a parody of Vogue, if that’s not obvious). I was reading “Vague” from my late teens—I still have most issues—and it had a great deal to do with shaping how I see the world. Marcus cribbed a lot from Tom Vague for Lipstick Traces, which is not to take anything away from Greil Marcus at all, but to simply give credit where its due.

Although I can recall a lot of criticism that was leveled at Lipstick Traces by reviewers when it first came out, the book’s thesis was, in my opinion, on pretty firm ground. It has certainly stood the test of time and has remained in print to this day. I’m told that it’s often used in college courses, which is unsurprising. A twentieth anniversary edition of Lipstick Traces was published by Harvard Press in 2009

But what many ardent admirers of the book don’t know, it that Rough Trade released a companion “soundtrack” CD to Lipstick Traces that came out in 1993. Like the book, it’s always had pride of place in my vast collection of “stuff.” The CD was rarely encountered in a world prior to Amazon.com (there’s not even a listing for it on Amazon today, either) but now, thanks to the fine folks at Ubuweb, these rare audio documents, lovingly assembled by Marcus, can be heard again. The selection runs the gamut of weird old hillbilly folk, doo-wop, to punk rock from the Slits, Buzzcocks. Gang of Four, The Adverts, Kleenex/Liliput, The Raincoats, The Mekons, a recording of the audience at a Clash gig, and best of all, the blistering mutant be-bop of Essential Logic’s “Wake Up.” Interspersed between the music is spoken word material from French philosopher Guy Debord, Triatan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck and even Marie Osmond reciting a brain-damaged version of Hugo Ball’s nonsense poem “Karawane” that must be heard to be believed.

Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century

Greil Marcus

Published 1989

Art

Greil Marcus, author of "Mystery Train", widely acclaimed as the best book ever written about America as seen through its music, began work on this new book out of a fascination with the Sex Pistols: that scandalous antimusical group, invented in London in 1975 and dead within two years, which sparked the emergence of the culture called punk. 'I am an antichrist!' shouted singer Johnny Rotten - where in the world of pop music did that come from? Looking for an answer, with a high sense of the drama of the journey, Marcus takes us down the dark paths of counterhistory, a route of blasphemy, adventure, and surprise. This is no mere search for cultural antecedents. Instead, what Marcus so brilliantly shows is that various kinds of angry, absolute demands - demands on society, art, and all the governing structures of everyday life - seem to be coded in phrases, images, and actions passed on invisibly, but inevitably, by people quite unaware of each other. Marcus lets us hear strange yet familiar voices: of such heretics as the Brethren of the Free Spirit in medieval Europe and the Ranters in seventeenth-century England; the dadaists in Zurich in 1916 and Berlin in 1918, wearing death masks, chanting glossolalia; one Michel Mourre, who in 1950 took over Easter Mass at Notre-Dame to proclaim the death of God; the Lettrist International and the Situationist International, small groups of Paris-based artists and writers surrounding Guy Debord, who produced blank-screen films, prophetic graffiti, and perhaps the most provocative social criticism of the 1950s and '60s; the rioting students and workers of May '68, scrawling cryptic slogans on city walls and bringing France to a halt; and, the Sex Pistols in London, recording the savage "Anarchy in the U.K.", and "God Save the Queen". Although the Sex Pistols shape the beginning and the end of the story, "Lipstick Traces" is not a book about music; it is about a common voice, discovered and transmitted in many forms. Working from scores of previously unexamined and untranslated essays, manifestos, and filmscripts, from old photographs, dada sound poetry, punk songs, collages, and classic texts from Marx to Henri Lefebvre, Marcus takes us deep behind the acknowledged events of our era, into a hidden tradition of moments that would seem imaginary except for the fact that they are real: a tradition of shared utopias, solitary refusals, impossible demands, and unexplained disappearances. Written with grace and force, humor and an insistent sense of tragedy and danger, "Lipstick Traces" tells a story as disruptive and compelling as the century itself.

A Review «LIPSTICK TRACES: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century» by Greil Marcus

Article (PDF Available) · April 1989

Kevin Anthony Brown

5.17

City University of New York

Abstract

The title here, taken from the 1962 hit lyrics "Lipstick traces/On a cigarette," aptly sums up Marcus' (Village Voice columnist; Mystery Train, 1975) paradoxical project--which amounts to fashioning a text on the enduring aspects of the "hidden history" of modernism as revealed in that imprint of the ephemeral, pop music.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338912438_A_Review_LIPSTICK_TRACES_A_Secret_History_of_the_Twentieth_Century_by_Greil_Marcus

Below, Benny Spellman: “Lipstick Traces (On A Cigarette)”

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338912438_A_Review_LIPSTICK_TRACES_A_Secret_History_of_the_Twentieth_Century_by_Greil_Marcus

Below, Benny Spellman: “Lipstick Traces (On A Cigarette)”

__

__