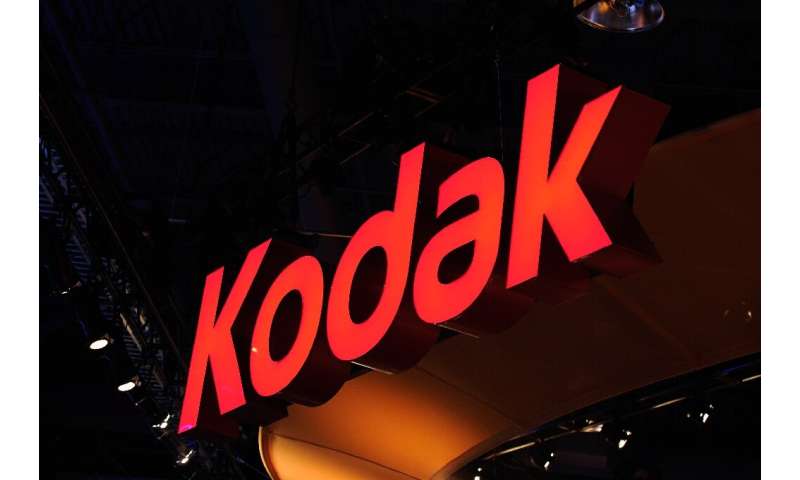

Shares of Eastman Kodak plunged after a US agency suspended activity on a $765 million loan to support the company's shift into pharmaceuticals

Shares of Kodak plunged Monday after a US agency suspended a loan intended to support the former photo giant's launch of a new pharmaceutical venture.

The US International Development Finance Corporation's (DFC) said Friday it will halt further action following controversy that has surrounded its July 28 announcement of a $765 million loan to Kodak.

The loan is part of a program to boost US pharmaceutical capacity in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Shares of Eastman Kodak dove 28.3 percent to $10.67 in afternoon trading.

The Wall Street Journal has reported that the Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating Kodak's disclosures about the loans and is expected to probe the company's awarding of stock option grants to executives on July 27.

Trading volumes in Kodak surged the day before the DFC announcement and shares rocketed up as much as 500 percent on July 28 after the loan's announcement.

"On July 28, we signed a letter of interest with Eastman Kodak," DFC said on Twitter on Friday. "Recent allegations of wrongdoing raise serious concerns.

"We will not proceed any further unless these allegations are cleared."

Kodak on Friday appointed a special committee to oversee an internal review "of recent activity by the Company and related parties" connected to the DFC announcement.

The DFC loan to Kodak would be the first to be made after President Donald Trump in May signed an executive order aimed at encouraging domestic production of materials needed to fight COVID-19.

Senior House Democrats have also questioned the loan.

A group of lawmakers including Maxine Waters, chairwoman of the financial services committee, and Eliot Engel, chairman of the foreign affairs committee, sent a letter last week to the DFC noting that Kodak's prior attempt at pharmaceutical manufacturing was "unsuccessful."

Explore further Kodak lands loan to bolster US-produced drug supply

Shares of Kodak plunged Monday after a US agency suspended a loan intended to support the former photo giant's launch of a new pharmaceutical venture.

The US International Development Finance Corporation's (DFC) said Friday it will halt further action following controversy that has surrounded its July 28 announcement of a $765 million loan to Kodak.

The loan is part of a program to boost US pharmaceutical capacity in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Shares of Eastman Kodak dove 28.3 percent to $10.67 in afternoon trading.

The Wall Street Journal has reported that the Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating Kodak's disclosures about the loans and is expected to probe the company's awarding of stock option grants to executives on July 27.

Trading volumes in Kodak surged the day before the DFC announcement and shares rocketed up as much as 500 percent on July 28 after the loan's announcement.

"On July 28, we signed a letter of interest with Eastman Kodak," DFC said on Twitter on Friday. "Recent allegations of wrongdoing raise serious concerns.

"We will not proceed any further unless these allegations are cleared."

Kodak on Friday appointed a special committee to oversee an internal review "of recent activity by the Company and related parties" connected to the DFC announcement.

The DFC loan to Kodak would be the first to be made after President Donald Trump in May signed an executive order aimed at encouraging domestic production of materials needed to fight COVID-19.

Senior House Democrats have also questioned the loan.

A group of lawmakers including Maxine Waters, chairwoman of the financial services committee, and Eliot Engel, chairman of the foreign affairs committee, sent a letter last week to the DFC noting that Kodak's prior attempt at pharmaceutical manufacturing was "unsuccessful."

Explore further Kodak lands loan to bolster US-produced drug supply