New global study shows 'best of the last' tropical forests urgently need protection

by Northern Arizona University

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Credit: CC0 Public DomainThe world's 'best of the last' tropical forests are at significant risk of being lost, according to a paper released today in Nature Ecology and Evolution. Of these pristine forests that provide key services—including carbon storage, prevention of disease transmission and water provision—only a mere 6.5 percent are formally protected.

In the study, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Wildlife Conservation Society and scientists from eight leading research institutions—including professor Scott Goetz, research professor Patrick Jantz and research associate Pat Burns of Northern Arizona University' School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems—identified significant omissions in international forest conservation strategies. Current global targets focus solely on forest extent and fail to acknowledge the importance of forest intactness, or structural condition, creating a critical gap in action to safeguard ecosystems essential for human and planetary well-being.

New targets that recognize forest quality are urgently needed to safeguard the Earth's precious humid tropical forests. Of the 1.9 million hectares of humid tropical forests globally, the study advocated for new protections in 41 percent of these areas, active restoration in 7 percent and reduction of human pressure in 19 percent to promote coordinated strategies to sustain forests of high ecological value.

"By serving as a convener to bring together the world's best scientists with governments, UNDP plays a critical role in ensuring that cutting-edge research is relevant for the development of key international agreements and implementation at the national level," commented Haoliang Xu, UN Assistant Secretary-General and UNDP Director of Bureau for Policy and Programme Support.

Collaborating with UNDP Country Offices and key stakeholders in Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ecuador, Indonesia, Peru, and Viet Nam, researchers mapped the location of high-quality forests using recently developed high-resolution maps of forest structure and human pressure across the global humid tropics.

The paper reveals that the Earth's humid tropical forests, only half of which have high ecological integrity, are largely limited to the Amazon and Congo Basins. The vast majority of these forests have no formal protection and, given recent rates of loss, are at significant risk.

With the rapid disappearance of these 'best of the last' forests at stake, the paper provides a policy-driven framework for their conservation and restoration, recommending locations to maintain protections, add new protections, restore forest structure, and mitigate human pressure.

The coming year is a so-called 'super year' for biodiversity, in which the world will agree on a new deal for nature that will shape global action for the next 30 years. Countries will also have a final chance to revise their contributions to reduce carbon emissions before the Paris Climate Agreement goes into effect. Both these milestones will impact efforts to advance the nature-based Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda.

"The work reported in this paper is the result of a long process assessing the condition of the world's tropical forests," said Goetz, a co-author of the paper. "The breakthrough here was being able to use spaceborne satellite data to provide the first robust estimates of the structural condition of forests in three dimensions, not just forest canopy cover."

"Advances in earth observation instruments and methodologies developed by NASA and partner institutions, coupled with the use of incredibly powerful computing systems like NAU's Monsoon and Google Earth Engine, enabled a near-global mapping of tropical forest quality. We synthesized the best available earth observation datasets to map the changing condition of the Earth's tropical forests, finding that only 6.5 percent of the highest quality tropical forests are formally protected. We hope that the conservation strategies proposed as part of this international effort will be a step towards conserving high quality forests and restoring those that have been degraded," said Burns.

"Every year, research reveals new ways that old, structurally complex forests contribute to biodiversity, carbon storage, water resources, and many other ecosystem services. That we can now map such forests in great detail is an important step forward in efforts to conserve them," said Jantz.

Explore further Saving Africa's biggest trees to help Earth breathe

More information: Hansen, A.J., Burns, P., Ervin, J. et al. A policy-driven framework for conserving the best of Earth's remaining moist tropical forests. Nat Ecol Evol (2020). doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1274-7

Journal information: Nature Ecology & Evolution

Provided by Northern Arizona University

Schoolgirls in Sulawesi, Indonesia: is the language divide also a class divide? Credit: Shutterstock

Schoolgirls in Sulawesi, Indonesia: is the language divide also a class divide? Credit: Shutterstock

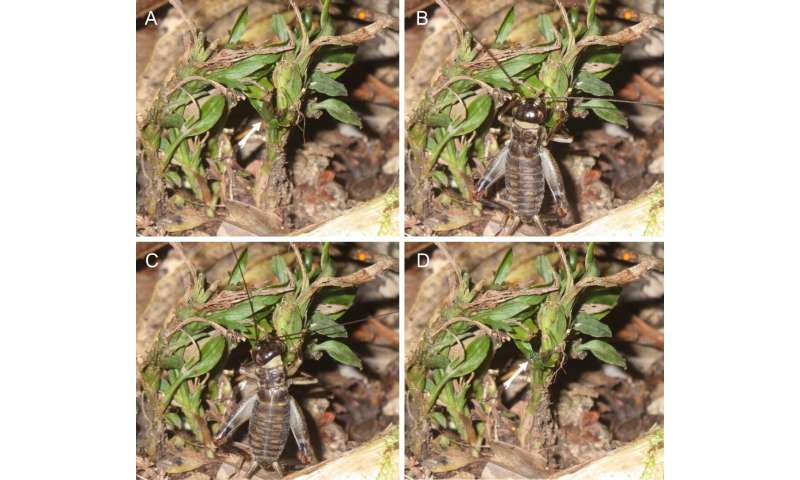

Sequential photographs of the cricket Eulandrevus ivani consuming an Apostasia nipponica fruit (indicated by arrows). An entire fruit was consumed during a single visit by the cricket. Credit: Kenji Suetsugu

Sequential photographs of the cricket Eulandrevus ivani consuming an Apostasia nipponica fruit (indicated by arrows). An entire fruit was consumed during a single visit by the cricket. Credit: Kenji Suetsugu