Grist / Amelia Bates

COVER STORY

Growing Pains

Post-COVID, should countries rethink their obsession with economic growth?

By Shannon Osaka on Aug 11, 2020

In 1968, a small group of elite academics, industrialists, and government officials gathered at a Roman villa to discuss “the predicament of mankind.” They called themselves the Club of Rome, and, in a largely impenetrable document filled with bizarre flow charts and words like “problematique,” they laid out a plan to analyze the major issues facing humanity with the new technology of computer modeling.

“We proceed from the belief that problems have ‘solutions,’” they wrote. Their goal was to find them.

The result, a 200-page book called The Limits to Growth published in 1972, forever changed the contours of the burgeoning environmental movement. The thesis was simple: The planet simply could not sustain current rates of economic and population growth. “The most probable result,” the group predicted, “will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.” In other words, humanity would have to hit the brakes — or suffer the collapse of society as we know it.

The book was met with scorn and a pile-on in the mainstream media. Three economists writing in the New York Times called it “an empty and misleading work” that was “little more than polemical fiction.” Henry Wallich, an economist and columnist for Newsweek, wrote that it amounted to “a piece of irresponsible nonsense.”

Nevertheless, the ideas that sprang out of that meeting in Rome gained traction. A year later, a geologist testifying before Congress quipped, “Anyone who believes growth can go on forever is either a madman or an economist.” The environmental historian David Worster wrote in 2016 that The Limits to Growth was “the book that cried wolf. The wolf was the planet’s decline, and the wolf was real.”

Half a century after The Limits to Growth, the future of the planet certainly doesn’t look bright. Since the book was published, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has shot up, from around 327 parts per million in 1972 to 416 parts per million today. (Scientists had warned that passing 350 parts per million risked dangerous warming.) Global temperatures, meanwhile, have climbed almost 2 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1 degree Celsius, since pre-industrial times — fueling extreme weather events, catastrophic heat waves in the Arctic, and steadily rising sea levels. Last year, a United Nations report found that humans are altering the planet so thoroughly that up to 1 million species face extinction.

Firefighters fight to extinguish forest fires near the village of Batagay, Sakha Republic in Yakutia. Russian Emergency Ministry / AFP / Getty Images

One of the Club’s chief concerns — that runaway population growth would torch the environment — has fallen out of favor in recent years. (After all, birth rates in developed countries, which use the most resources and have the largest environmental footprint, are on the decline.) But economic growth is another beast entirely. For decades, environmentalists have squabbled over whether the production of more and more stuff, year after year, is to blame for the mess the planet is in. The green movement has split into those who believe growth can continue under new, more sustainable conditions, and an increasingly vocal minority who believe that “green growth” is at best an oxymoron, at worst a distracting fantasy.

These two camps have remained in an uneasy alliance, working toward common goals of conservation and clean energy. Now as the COVID-19 pandemic cripples the world’s economy — which is expected to shrink by at least 6 percent this year — the debate over growth has been thrust into the spotlight. Fifty years after Limits to Growth, many economists and environmentalists are reconsidering its lessons, questioning whether economic growth is in fact compatible with a sustainable world — and if not, how else governments can measure the success (or failure) of modern societies.

There are whole industries built on the idea that the way to save the planet is to paint the economy green. Replace plastic plates with compostable ones. Trade in a gas-guzzling Jeep for a Toyota Prius. In other words, most economists believe that the world’s economies can continue to produce more, but in a “green” way: more housing, more electronics, more cars — but also more solar panels, more wind turbines, and more electric vehicles. “Greening growth is necessary, efficient, and affordable,” declared the World Bank in a 2012 report.

These “green-growthers” argue that new low-carbon technologies, combined with a steady shift toward producing more services (think day-care centers or community theater), can make continued growth sustainable. This kind of “have your cake and eat it too” mentality has become the dominant way of thinking about how to turn the giant, fossil-fuel spewing world economy around.

But others think economic growth, no matter how green, imperils the planet. They believe governments should either purposefully shrink their economies — an idea often known as “degrowth” — or, at the very least, not grow any further. “Material growth cannot continue indefinitely because planet Earth is physically limited,” wrote the ecological economist Tim Jackson in his 2009 book Prosperity with Growth. “Living well on a finite planet cannot simply be about consuming more and more stuff.” (The Club of Rome, for its part, suggested that civilizational collapse could be averted if society came to accept “self-imposed” limits.)

The degrowth camp has largely stayed on the fringes of environmental thought. In recent years, however, as the climate crisis has intensified, its critique has crept into the mainstream, with degrowth-focused books, journals, and conferences. The idea has also found a home in activist circles: It’s popular among members of the U.K.-based group Extinction Rebellion, who brought the city of London to a halt in October with protests against the government’s sluggish response to climate change. You can hear its influence in speeches by Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish activist. “We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth,” she said during a United Nations climate summit last year. “How dare you!”

Extinction Rebellion environmental activists stage a loud demonstration in July outside the Bank of England to protest against the distribution of funds to carbon-intensive industries. Wiktor Szymanowicz / NurPhoto / Getty Images

The most radical members of this group think wealthy, developed countries should shrink their economies to fit within ecological limits — curbing consumption and energy use enough to save huge swaths of the planet from destruction and prevent runaway climate change. “Degrowth signifies a desired direction, one in which societies will use fewer natural resources and will organize and live differently than today,” writes Giorgos Kallis, an ecological economist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, in Degrowth: A New Vocabulary.

How such a transition could be made politically palatable, or managed without impoverishing millions and setting off widespread unrest in the United States, Europe, and China, is largely left to the imagination.

Others within the movement take a moderate approach, calling for a re-balancing of priorities (health care and education instead of corporate profit) as opposed to throwing the economy into reverse. Tim Jackson, the author of Prosperity without Growth and a professor of sustainable development at the University of Surrey in England, considers himself a supporter of “post-growth,” which suggests turning away from growth, instead of actively trying to suppress it. “Would it not be better,” he writes, “to halt the relentless pursuit of growth in the advanced economies and concentrate instead on sharing out the available resources more equitably?”

At the heart of debates between green-growthers and degrowthers lies a simple question: Can the global economy — that giant engine which has spent centuries sucking down fossil fuels and spitting up material goods — be separated from environmental destruction?

Historically, big industries have relied on coal and oil — and so pollution, especially carbon emissions, has followed the economy’s lead. During downturns, like the Great Recession, emissions drop — sometimes precipitously, only to resurge when the economy turns around. Take the COVID-19 pandemic: As shutdowns put millions out of work in April, worldwide carbon emissions plunged by 17 percent. By mid-June, however, as cars returned to city streets and businesses cautiously reopened, emissions were nearly back to their pre-pandemic levels.

In April, during the COVID-19 lockdown, light traffic passes on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles during what would normally be the evening rush hour. Mario Tama / Getty Images

Green-growthers argue that technology and innovation can break this pattern — that is, growth can be “decoupled” from rising emissions. There have been a few promising examples in recent decades: Between 2000 and 2014, the United States and 20 other countries saw their gross domestic product rise even as their carbon emissions fell. In the U.S., the decline was thanks to a dramatic shift from coal to natural gas and renewables; in Europe, carbon taxes and a move away from heavy industry dragged down emissions. On a larger scale, the world economy grew around 3 percent per year from 2014 to 2016, yet global carbon emissions didn’t budge.

Critics of economic growth, however, see these as exceptions that prove the rule. Splitting emissions from growth is “totally outside historical experience,” Jackson told Grist. “That doesn’t mean it can’t be done, technically — but it does mean that it’s incredibly difficult, and that it’s very different from anything that we’ve done before.”

Jackson said that even though countries like the United States and the United Kingdom have temporarily separated emissions from growth, the bigger picture hasn’t changed much. In the roughly two-and-a-half decades since industrialized countries signed the Kyoto Protocol to slash carbon emissions, fossil fuel pollution has risen by a staggering 50 percent. And since that two-year breather ended in 2016, carbon emissions have been creeping up again. “Absolute decoupling,” Jackson wrote in Prosperity without Growth, “is nowhere to be seen.”

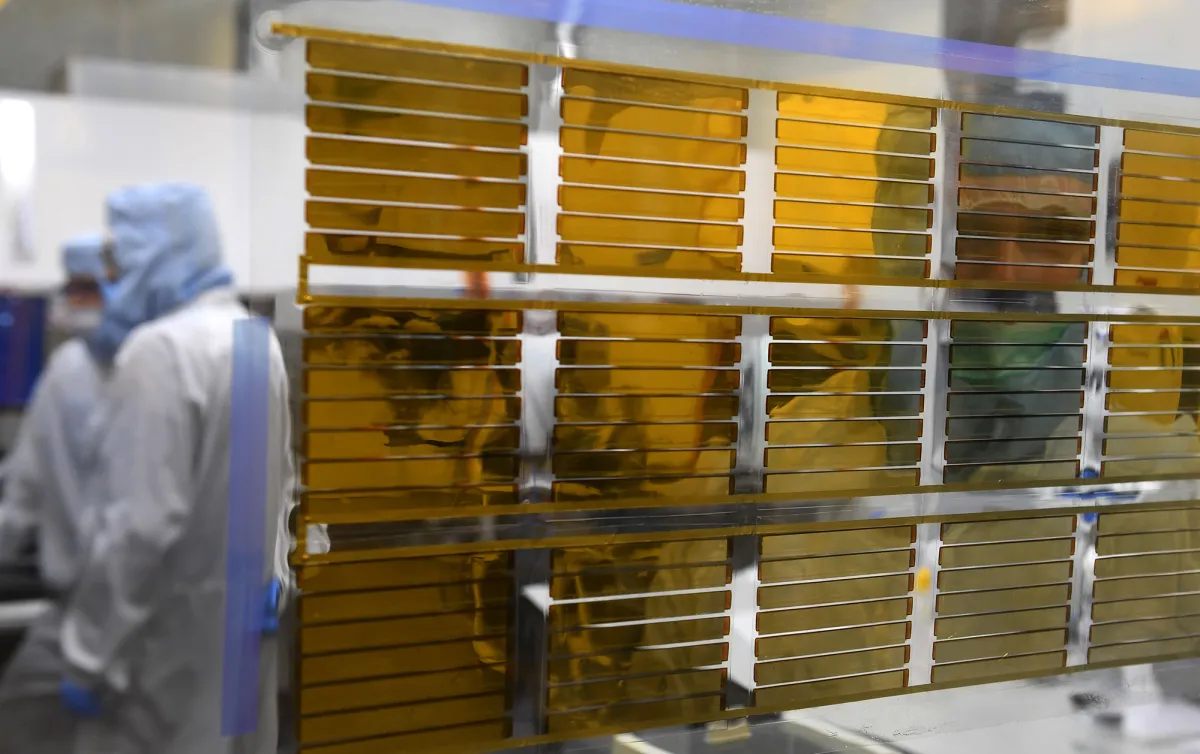

But what if setting growth free from CO2 emissions will just take more time, and more technology — bigger batteries, for example, and cheaper solar panels? Cameron Hepburn, a professor of environmental economics at the University of Oxford, points out that there have been many instances in history where society has replaced a heavily polluting technology with a more efficient, cleaner technology — shifting from, say, kerosene lamps to incandescent lights to LED bulbs — without sacrificing growth. Why should the quest for fossil fuel-free energy be any different? “The thing I object to most is the idea that, just because it hasn’t been done yet, it can’t be done,” Hepburn said. He points out that degrowth hasn’t been tried, either — and so the hypothetical choice for governments is between two relatively unproven pathways.

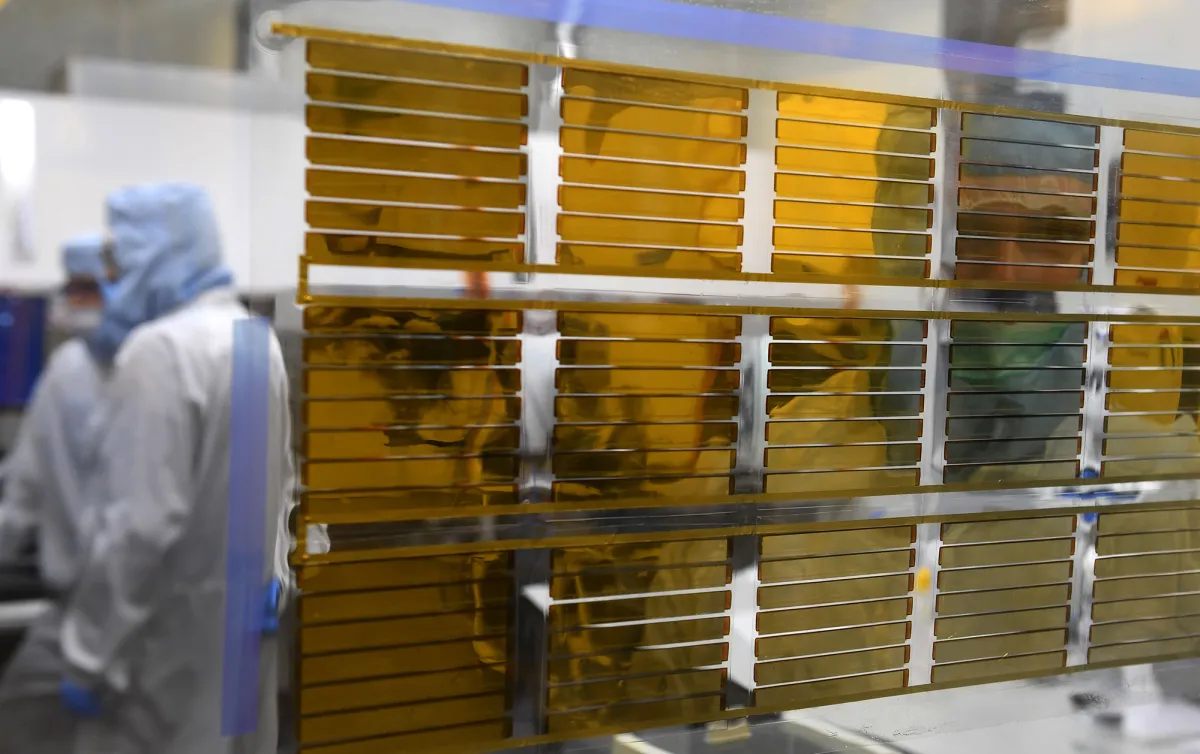

Experimental solar panels hang in the window of a Saule company laboratory in Wroclaw, Poland. Janek Skarzynski / AFP / Getty Images

Still, Hepburn’s argument makes some environmentalists uncomfortable. Sure, green growth sounds great — why not have more of everything, and save the planet at the same time? — but the transformation from the current economy to a new, cleaner one, would have to take place at a breakneck pace to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. This year, the coronavirus pandemic will likely cut global carbon emissions somewhere between 5 and 8 percent, the biggest drop since World War II. But to keep warming below 1.5 degrees C (or 2.7 degrees F) — widely considered by scientists as the point at which climate impacts go from bad to terrible — the world would have to decrease emissions by 7.6 percent every year from now until 2030. Nothing like that has ever happened before.

While decoupling growth from emissions seems to some like a pipe dream, slashing growth to stem emissions presents other problems. Some 1.9 billion people live on less than $3.20 a day, and around a third of them, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, try to survive on just $1.90 a day. It’s easy to talk about the problems that come with a growing economy when you live in a relatively affluent, developed country. Given the large numbers of people impoverished worldwide and the ever-present threat of climate change, Hepburn argues that green growth is the only way out.

Degrowth advocates, of course, aren’t oblivious to global poverty. In fact, many think that developing countries should continue to grow to lift their populations out of poverty, even if it means their emissions rise. To balance the impact on the overall planet, Jason Hickel, an anthropologist at the London School of Economics, makes the case that richer countries would have to do more with less. The United States, for instance, produces around $65,000 of economic goods and services per person. “Imagine cutting the GDP per capita of the U.S. down to less than half its present size, in real terms,” Hickel wrote in a blog post, referring to gross domestic product, the preeminent measure of economic activity. That would put Americans roughly on par with Europeans. “I live in Europe,” Hickel added. “It’s hardly a dystopia.”

Of course, chopping an economy in half doesn’t sound appealing when you’re already struggling to get by. Forty percent of households in the U.S. make less than $40,000 a year, and 15 percent earn less than $20,000. It’s hard to imagine telling those households to cut back when America’s one-percenters earn at least half a million every year — and own around 40 percent of the country’s wealth.

Members of National Nurses United union wave “Medicare for All” signs during a 2019 rally in front of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America in Washington. Bill Clark / CQ Roll Call / Getty Images

A cadre of ecological economists has suggested that a stronger safety net could help people in wealthier countries learn to get by with less. In a 2011 paper, Peter Victor, a professor emeritus at Toronto’s York University, used computer modeling to demonstrate that if Canada cut its economy by half over three decades, while also expanding adult education, anti-poverty programs, and other benefits, the country could reduce poverty and unemployment even while producing much, much less.

The majority of economists and politicians say, “‘There is no alternative; we have to go for growth in a market economy,’” Victor told Grist. “Well, that’s such a mind-numbing perspective. We try to make these models available so that people can get a better idea of what the alternatives are.”

While the idea of purposefully shrinking the economy is still a fringe position, more and more thinkers are getting on board with the idea of “post-growth,” or shifting away from growth as a dominant measure of human and societal well-being. Jackson, for example, wants to focus on “prosperity,” which could include growing food and making clothing, as well as even walking, reading, and building relationships. “I just kept coming back to the fact that, at the end of the day, GDP was trumping everything,” Jackson said. “All the decisions you might want to make about the quality of people’s working lives or doing something about climate change — they were all just being trumped by the pursuit of GDP.”

And he’s not the only one. University of Oxford economist Kate Raworth, for example, argues that the ideal economy should incorporate the ecological limits of the earth, providing shelter, health care, education, food, etc., while not compromising clean water, air, or soil. Herman Daly, a professor of economics at the University of Maryland, has proposed a “steady-state” economy that neither grows nor shrinks. (It’s akin to John Stuart Mill’s idea of a “stationary state” that could support “moral and social progress” and “room for improving the Art of Living.”)

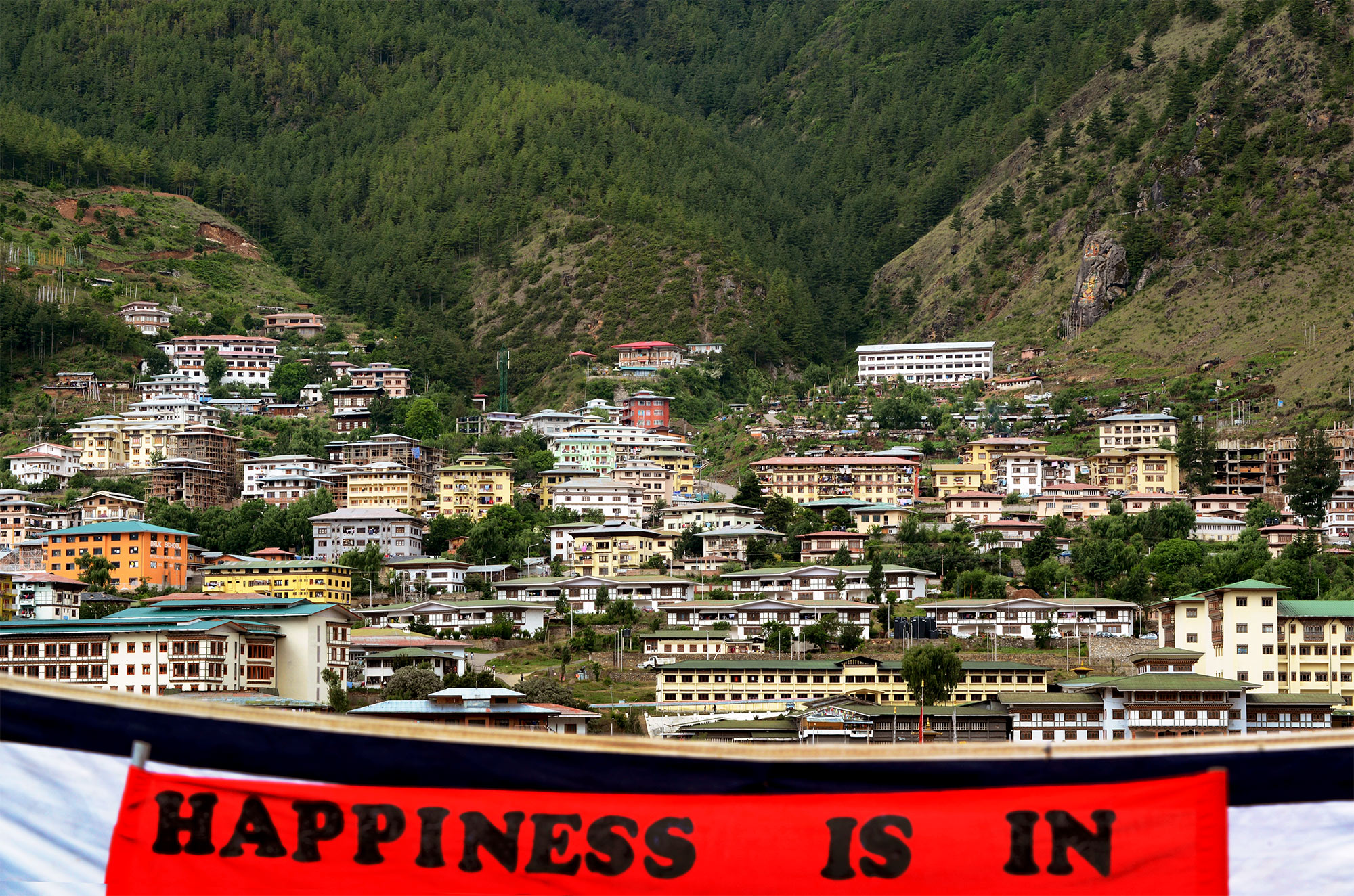

And some countries are getting on board with alternative views of successful societies. Under Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, who has lately become famous for eliminating COVID-19, New Zealand has created a “well-being budget” to complement GDP, which includes 61 indicators such as trust in government, water quality, general life satisfaction, and the unemployment rate. The South Asian country of Bhutan has been measuring “gross national happiness” since the 1970s, assessing living standards, health, education, and psychological well-being.

A banner making a reference to Gross National Happiness hangs in a field during a cultural event to celebrate the birth date of Bhutan’s fourth king at a local school in Thimphu on June 2, 2013. Roberto Schmidt / AFP / Getty Images

There may be another reason that these alternatives are gaining popularity, at least among academics: Despite the best efforts of the world’s governments, growth has in recent decades been sluggish, especially for developed countries. The highest rate of global growth ever recorded was 4.15 percent in 1964. Since 2006, it has rarely topped 2 percent.

“It’s incredible,” said Danny Dorling, a professor of geography at the University of Oxford: “Every decade there’s less growth from the decade before. And every time it happens, people go, ‘Oh, that’s due to the oil shock, or, that’s due to the crash of 2008 and 2009.’ But I think we’ve been heading for a long time towards zero growth.”

Dorling thinks that we are reaching the end of “the Great Acceleration” — that period of rising prosperity and population growth that followed World War II. Similarly, Princeton University economist Robert Gordon writes in The Rise and Fall of American Growth that the period from 1870 to 1970 constituted a “special century” in which rapid technological innovation (electric lights, flushing toilets, the birth of the automobile) and new energy sources fast-tracked economic growth. That century, Gordon argued, was thrilling and unique — there was virtually no economic growth for thousands of years before 1770 — and is unrepeatable.

Dorling doesn’t think the end of growth is necessarily a bad thing. “If you think that economic growth can and should rise year after year,” Dorling writes in his new book Slowdown, “then you will find the synchronized slowdown of today as frightening as the screak of the sharp slamming on of the brakes of a train.”

But it could offer opportunities to live and work differently. It’s “not the end of history,” Dorling continues, “just the end of the roller coaster.”

The coronavirus pandemic, now resurgent across much of the world, has injected a sense of urgency around discussions of economic growth. In May, a group of more than 1,100 degrowth advocates signed a manifesto calling on governments to seize the moment to shift toward a “radically different kind of society, rather than desperately trying to get the destructive growth machine running again.”

When everything seems to be falling apart, the question of how to rebuild becomes more pressing than ever. In the United States alone, nearly 33 million people are now claiming unemployment benefits, with another 8 million falling out of the workforce. According to recent reports, the country’s GDP shrank by 9.2 percent between April and June, the worst contraction on record. Meanwhile, the World Bank projects that COVID-19 could force 71 million people into extreme poverty.

In June, hundreds of unemployed Kentucky residents wait in long lines outside the Kentucky Career Center in Frankfort for help with their unemployment claims. John Sommers II / Getty Images

For some, the virus has reinforced a conviction that ideas that first sprung from the Club of Rome were wrong: Zeroing out economic growth won’t solve the world’s biggest problems. Hepburn, the Oxford environmental economist, pointed out that even deep recessions couldn’t slow carbon emissions for long. “Look at the rebounds that are happening already,” he said. “Chinese emissions are now above pre-corona.” What’s more, the difficulty of enforcing and maintaining lockdowns shows the challenges of overhauling an entire society to live with less. “The idea that we would just voluntarily dial back in order to get environmental outcomes is just fantasy,” he said. “People don’t want to give up the things that they enjoy.”

But for others, COVID-19’s complete devastation of the economy, combined with its (very) brief reprieve from pollution, points to much deeper problems. After all, some of the richest countries in the world — including the United States — have failed miserably to protect their poorest and most vulnerable from a highly infectious disease. “There already is a tendency to want to rush back to normal,” Jackson said. “But there’s also a very narrow window of being able to say: ‘Is normal really what we want to rush back to?’