Our energy hunger is tethered to our economic past: study

by Paul Gabrielsen, University of Utah

by Paul Gabrielsen, University of Utah

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Just as a living organism continually needs food to maintain itself, an economy consumes energy to do work and keep things going. That consumption comes with the cost of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, though. So, how can we use energy to keep the economy alive without burning out the planet in the process?

In a paper in PLOS ONE, University of Utah professor of atmospheric sciences Tim Garrett, with mathematician Matheus Grasselli of McMaster University and economist Stephen Keen of University College London, report that current world energy consumption is tied to unchangeable past economic production. And the way out of an ever-increasing rate of carbon emissions may not necessarily be ever-increasing energy efficiency—in fact it may be the opposite.

"How do we achieve a steady-state economy where economic production exists, but does not continually increase our size and add to our energy demands?" Garrett says. "Can we survive only by repairing decay, simultaneously switching existing fossil infrastructure to a non-fossil appetite? Can we forget the flame?"

Thermoeconomics

Garrett is an atmospheric scientist. But he recognizes that atmospheric phenomena, including rising carbon dioxide levels and climate change, are tied to human economic activity. "Since we model the earth system as a physical system," he says, "I wondered whether we could model economic systems in a similar way."

He's not alone in thinking of economic systems in terms of physical laws. There's a field of study, in fact, called thermoeconomics. Just as thermodynamics describe how heat and entropy (disorder) flow through physical systems, thermoeconomics explores how matter, energy, entropy and information flow through human systems.

Many of these studies looked at correlations between energy consumption and current production, or gross domestic product. Garrett took a different approach; his concept of an economic system begins with the centuries-old idea of a heat engine. A heat engine consumes energy at high temperatures to do work and emits waste heat. But it only consumes. It doesn't grow.

Now envision a heat engine that, like an organism, uses energy to do work not just to sustain itself but also to grow. Due to past growth, it requires an ever-increasing amount of energy to maintain itself. For humans, the energy comes from food. Most goes to sustenance and a little to growth. And from childhood to adulthood our appetite grows. We eat more and exhale an ever-increasing amount of carbon dioxide.

"We looked at the economy as a whole to see if similar ideas could apply to describe our collective maintenance and growth," Garrett says. While societies consume energy to maintain day to day living, a small fraction of consumed energy goes to producing more and growing our civilization.

"We've been around for a while," he adds. "So it is an accumulation of this past production that has led to our current size, and our extraordinary collective energy demands and CO2 emissions today."

Growth as a symptom

To test this hypothesis, Garrett and his colleagues used economic data from 1980 to 2017 to quantify the relationship between past cumulative economic production and the current rate at which we consume energy. Regardless of the year examined, they found that every trillion inflation-adjusted year 2010 U.S. dollars of economic worldwide production corresponded with an enlarged civilization that required an additional 5.9 gigawatts of power production to sustain itself . In a fossil economy, that's equivalent to around 10 coal-fired power plants, Garrett says, leading to about 1.5 million tons of CO2 emitted to the atmosphere each year. Our current energy usage, then, is the natural consequence of our cumulative previous economic production.

They came to two surprising conclusions. First, although improving efficiency through innovation is a hallmark of efforts to reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, efficiency has the side effect of making it easier for civilization to grow and consume more.

Second, that the current rates of world population growth may not be the cause of rising rates of energy consumption, but a symptom of past efficiency gains.

"Advocates of energy efficiency for climate change mitigation may seem to have a reasonable point," Garrett says, "but their argument only works if civilization maintains a fixed size, which it doesn't. Instead, an efficient civilization is able to grow faster. It can more effectively use available energy resources to make more of everything, including people. Expansion of civilization accelerates rather than declines, and so do its energy demands and CO2 emissions."

A steady-state decarbonized future?

So what do those conclusions mean for the future, particularly in relation to climate change? We can't just stop consuming energy today any more than we can erase the past, Garrett says. "We have inertia. Pull the plug on energy consumption and civilization stops emitting but it also becomes worthless. I don't think we could accept such starvation."

But is it possible to undo the economic and technological progress that have brought civilization to this point? Can we, the species who harnessed the power of fire, now "forget the flame," in Garrett's words, and decrease efficient growth?

"It seems unlikely that we will forget our prior innovations, unless collapse is imposed upon us by resource depletion and environmental degradation," he says, "which, obviously, we hope to avoid."

So what kind of future, then, does Garrett's work envision? It's one in which the economy manages to hold at a steady state—where the energy we use is devoted to maintaining our civilization and not expanding it.

It's also one where the energy of the future can't be based on fossil fuels. Those have to stay in the ground, he says.

"At current rates of growth, just to maintain carbon dioxide emissions at their current level will require rapidly constructing renewable and nuclear facilities, about one large power plant a day. And somehow it will have to be done without inadvertently supporting economic production as well, in such a way that fossil fuel demands also increase."

It's a "peculiar dance," he says, between eliminating the prior fossil-based innovations that accelerated civilization expansion, while innovating new non-fossil fuel technologies. Even if this steady-state economy were to be implemented immediately, stabilizing CO2 emissions, the pace of global warming would be slowed—not eliminated. Atmospheric levels of CO2 would still reach double their pre-industrial level before equilibrating, the research found.

By looking at the global economy through a thermodynamic lens, Garrett acknowledges that there are unchangeable realities. Any form of an economy or civilization needs energy to do work and survive. The trick is balancing that with the climate consequences.

"Climate change and resource scarcity are defining challenges of this century," Garrett says. "We will not have a hope of surviving our predicament by ignoring physical laws."

Future work

This study marks the beginning of the collaboration between Garrett, Grasselli and Keen. They're now working to connect the results of this study with a full model for the economy, including a systematic investigation of the role of matter and energy in production.

"Tim made us focus on a pretty remarkable empirical relationship between energy consumption and cumulative economic output," Grasselli says. "We are now busy trying to understand what this means for models that include notions that are more familiar to economists, such as capital, investment and the always important question of monetary value and inflation."

Explore further

Just as a living organism continually needs food to maintain itself, an economy consumes energy to do work and keep things going. That consumption comes with the cost of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, though. So, how can we use energy to keep the economy alive without burning out the planet in the process?

In a paper in PLOS ONE, University of Utah professor of atmospheric sciences Tim Garrett, with mathematician Matheus Grasselli of McMaster University and economist Stephen Keen of University College London, report that current world energy consumption is tied to unchangeable past economic production. And the way out of an ever-increasing rate of carbon emissions may not necessarily be ever-increasing energy efficiency—in fact it may be the opposite.

"How do we achieve a steady-state economy where economic production exists, but does not continually increase our size and add to our energy demands?" Garrett says. "Can we survive only by repairing decay, simultaneously switching existing fossil infrastructure to a non-fossil appetite? Can we forget the flame?"

Thermoeconomics

Garrett is an atmospheric scientist. But he recognizes that atmospheric phenomena, including rising carbon dioxide levels and climate change, are tied to human economic activity. "Since we model the earth system as a physical system," he says, "I wondered whether we could model economic systems in a similar way."

He's not alone in thinking of economic systems in terms of physical laws. There's a field of study, in fact, called thermoeconomics. Just as thermodynamics describe how heat and entropy (disorder) flow through physical systems, thermoeconomics explores how matter, energy, entropy and information flow through human systems.

Many of these studies looked at correlations between energy consumption and current production, or gross domestic product. Garrett took a different approach; his concept of an economic system begins with the centuries-old idea of a heat engine. A heat engine consumes energy at high temperatures to do work and emits waste heat. But it only consumes. It doesn't grow.

Now envision a heat engine that, like an organism, uses energy to do work not just to sustain itself but also to grow. Due to past growth, it requires an ever-increasing amount of energy to maintain itself. For humans, the energy comes from food. Most goes to sustenance and a little to growth. And from childhood to adulthood our appetite grows. We eat more and exhale an ever-increasing amount of carbon dioxide.

"We looked at the economy as a whole to see if similar ideas could apply to describe our collective maintenance and growth," Garrett says. While societies consume energy to maintain day to day living, a small fraction of consumed energy goes to producing more and growing our civilization.

"We've been around for a while," he adds. "So it is an accumulation of this past production that has led to our current size, and our extraordinary collective energy demands and CO2 emissions today."

Growth as a symptom

To test this hypothesis, Garrett and his colleagues used economic data from 1980 to 2017 to quantify the relationship between past cumulative economic production and the current rate at which we consume energy. Regardless of the year examined, they found that every trillion inflation-adjusted year 2010 U.S. dollars of economic worldwide production corresponded with an enlarged civilization that required an additional 5.9 gigawatts of power production to sustain itself . In a fossil economy, that's equivalent to around 10 coal-fired power plants, Garrett says, leading to about 1.5 million tons of CO2 emitted to the atmosphere each year. Our current energy usage, then, is the natural consequence of our cumulative previous economic production.

They came to two surprising conclusions. First, although improving efficiency through innovation is a hallmark of efforts to reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, efficiency has the side effect of making it easier for civilization to grow and consume more.

Second, that the current rates of world population growth may not be the cause of rising rates of energy consumption, but a symptom of past efficiency gains.

"Advocates of energy efficiency for climate change mitigation may seem to have a reasonable point," Garrett says, "but their argument only works if civilization maintains a fixed size, which it doesn't. Instead, an efficient civilization is able to grow faster. It can more effectively use available energy resources to make more of everything, including people. Expansion of civilization accelerates rather than declines, and so do its energy demands and CO2 emissions."

A steady-state decarbonized future?

So what do those conclusions mean for the future, particularly in relation to climate change? We can't just stop consuming energy today any more than we can erase the past, Garrett says. "We have inertia. Pull the plug on energy consumption and civilization stops emitting but it also becomes worthless. I don't think we could accept such starvation."

But is it possible to undo the economic and technological progress that have brought civilization to this point? Can we, the species who harnessed the power of fire, now "forget the flame," in Garrett's words, and decrease efficient growth?

"It seems unlikely that we will forget our prior innovations, unless collapse is imposed upon us by resource depletion and environmental degradation," he says, "which, obviously, we hope to avoid."

So what kind of future, then, does Garrett's work envision? It's one in which the economy manages to hold at a steady state—where the energy we use is devoted to maintaining our civilization and not expanding it.

It's also one where the energy of the future can't be based on fossil fuels. Those have to stay in the ground, he says.

"At current rates of growth, just to maintain carbon dioxide emissions at their current level will require rapidly constructing renewable and nuclear facilities, about one large power plant a day. And somehow it will have to be done without inadvertently supporting economic production as well, in such a way that fossil fuel demands also increase."

It's a "peculiar dance," he says, between eliminating the prior fossil-based innovations that accelerated civilization expansion, while innovating new non-fossil fuel technologies. Even if this steady-state economy were to be implemented immediately, stabilizing CO2 emissions, the pace of global warming would be slowed—not eliminated. Atmospheric levels of CO2 would still reach double their pre-industrial level before equilibrating, the research found.

By looking at the global economy through a thermodynamic lens, Garrett acknowledges that there are unchangeable realities. Any form of an economy or civilization needs energy to do work and survive. The trick is balancing that with the climate consequences.

"Climate change and resource scarcity are defining challenges of this century," Garrett says. "We will not have a hope of surviving our predicament by ignoring physical laws."

Future work

This study marks the beginning of the collaboration between Garrett, Grasselli and Keen. They're now working to connect the results of this study with a full model for the economy, including a systematic investigation of the role of matter and energy in production.

"Tim made us focus on a pretty remarkable empirical relationship between energy consumption and cumulative economic output," Grasselli says. "We are now busy trying to understand what this means for models that include notions that are more familiar to economists, such as capital, investment and the always important question of monetary value and inflation."

Explore further

How energy-intensive economies can survive and thrive as the globe ramps up climate action

More information: PLOS ONE (2020). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237672

Journal information: PLoS ONE

Provided by University of Utah

Civilization may need to 'forget the flame' to reduce CO2 emissions

More information: PLOS ONE (2020). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237672

Journal information: PLoS ONE

Provided by University of Utah

Civilization may need to 'forget the flame' to reduce CO2 emissions

Date:August 27, 2020

Source:University of Utah

Summary:Current world energy consumption is tied to unchangeable past economic production. And the way out of an ever-increasing rate of carbon emissions may not necessarily be ever-increasing energy efficiency -- in fact it may be the opposite.Share:

Just as a living organism continually needs food to maintain itself, an economy consumes energy to do work and keep things going. That consumption comes with the cost of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, though. So, how can we use energy to keep the economy alive without burning out the planet in the process?

In a paper in PLOS ONE, University of Utah professor of atmospheric sciences Tim Garrett, with mathematician Matheus Grasselli of McMaster University and economist Stephen Keen of University College London, report that current world energy consumption is tied to unchangeable past economic production. And the way out of an ever-increasing rate of carbon emissions may not necessarily be ever-increasing energy efficiency -- in fact it may be the opposite.

"How do we achieve a steady-state economy where economic production exists, but does not continually increase our size and add to our energy demands?" Garrett says. "Can we survive only by repairing decay, simultaneously switching existing fossil infrastructure to a non-fossil appetite? Can we forget the flame?"

Thermoeconomics

Garrett is an atmospheric scientist. But he recognizes that atmospheric phenomena, including rising carbon dioxide levels and climate change, are tied to human economic activity. "Since we model the earth system as a physical system," he says, "I wondered whether we could model economic systems in a similar way."

He's not alone in thinking of economic systems in terms of physical laws. There's a field of study, in fact, called thermoeconomics. Just as thermodynamics describe how heat and entropy (disorder) flow through physical systems, thermoeconomics explores how matter, energy, entropy and information flow through human systems.

Many of these studies looked at correlations between energy consumption and current production, or gross domestic product. Garrett took a different approach; his concept of an economic system begins with the centuries-old idea of a heat engine. A heat engine consumes energy at high temperatures to do work and emits waste heat. But it only consumes. It doesn't grow.

Now envision a heat engine that, like an organism, uses energy to do work not just to sustain itself but also to grow. Due to past growth, it requires an ever-increasing amount of energy to maintain itself. For humans, the energy comes from food. Most goes to sustenance and a little to growth. And from childhood to adulthood our appetite grows. We eat more and exhale an ever-increasing amount of carbon dioxide.

"We looked at the economy as a whole to see if similar ideas could apply to describe our collective maintenance and growth," Garrett says. While societies consume energy to maintain day to day living, a small fraction of consumed energy goes to producing more and growing our civilization.

"We've been around for a while," he adds. "So it is an accumulation of this past production that has led to our current size, and our extraordinary collective energy demands and CO2 emissions today."

Growth as a symptom

To test this hypothesis, Garrett and his colleagues used economic data from 1980 to 2017 to quantify the relationship between past cumulative economic production and the current rate at which we consume energy. Regardless of the year examined, they found that every trillion inflation-adjusted year 2010 U.S. dollars of economic worldwide production corresponded with an enlarged civilization that required an additional 5.9 gigawatts of power production to sustain itself . In a fossil economy, that's equivalent to around 10 coal-fired power plants, Garrett says, leading to about 1.5 million tons of CO2 emitted to the atmosphere each year. Our current energy usage, then, is the natural consequence of our cumulative previous economic production.

They came to two surprising conclusions. First, although improving efficiency through innovation is a hallmark of efforts to reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, efficiency has the side effect of making it easier for civilization to grow and consume more.

Second, that the current rates of world population growth may not be the cause of rising rates of energy consumption, but a symptom of past efficiency gains.

"Advocates of energy efficiency for climate change mitigation may seem to have a reasonable point," Garrett says, "but their argument only works if civilization maintains a fixed size, which it doesn't. Instead, an efficient civilization is able to grow faster. It can more effectively use available energy resources to make more of everything, including people. Expansion of civilization accelerates rather than declines, and so do its energy demands and CO2 emissions."

A steady-state decarbonized future?

So what do those conclusions mean for the future, particularly in relation to climate change? We can't just stop consuming energy today any more than we can erase the past, Garrett says. "We have inertia. Pull the plug on energy consumption and civilization stops emitting but it also becomes worthless. I don't think we could accept such starvation."

But is it possible to undo the economic and technological progress that have brought civilization to this point? Can we, the species who harnessed the power of fire, now "forget the flame," in Garrett's words, and decrease efficient growth?

"It seems unlikely that we will forget our prior innovations, unless collapse is imposed upon us by resource depletion and environmental degradation," he says, "which, obviously, we hope to avoid."

So what kind of future, then, does Garrett's work envision? It's one in which the economy manages to hold at a steady state -- where the energy we use is devoted to maintaining our civilization and not expanding it.

It's also one where the energy of the future can't be based on fossil fuels. Those have to stay in the ground, he says.

"At current rates of growth, just to maintain carbon dioxide emissions at their current level will require rapidly constructing renewable and nuclear facilities, about one large power plant a day. And somehow it will have to be done without inadvertently supporting economic production as well, in such a way that fossil fuel demands also increase."

It's a "peculiar dance," he says, between eliminating the prior fossil-based innovations that accelerated civilization expansion, while innovating new non-fossil fuel technologies. Even if this steady-state economy were to be implemented immediately, stabilizing CO2 emissions, the pace of global warming would be slowed -- not eliminated. Atmospheric levels of CO2 would still reach double their pre-industrial level before equilibrating, the research found.

By looking at the global economy through a thermodynamic lens, Garrett acknowledges that there are unchangeable realities. Any form of an economy or civilization needs energy to do work and survive. The trick is balancing that with the climate consequences.

"Climate change and resource scarcity are defining challenges of this century," Garrett says. "We will not have a hope of surviving our predicament by ignoring physical laws."

Future work

This study marks the beginning of the collaboration between Garrett, Grasselli and Keen. They're now working to connect the results of this study with a full model for the economy, including a systematic investigation of the role of matter and energy in production.

"Tim made us focus on a pretty remarkable empirical relationship between energy consumption and cumulative economic output," Grasselli says. "We are now busy trying to understand what this means for models that include notions that are more familiar to economists, such as capital, investment and the always important question of monetary value and inflation."

Journal Reference:

Timothy J. Garrett, Matheus Grasselli, Stephen Keen. Past world economic production constrains current energy demands: Persistent scaling with implications for economic growth and climate change mitigation. PLOS ONE, 2020; 15 (8): e0237672 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237672

University of Utah. "Civilization may need to 'forget the flame' to reduce CO2 emissions." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 27 August 2020.

Just as a living organism continually needs food to maintain itself, an economy consumes energy to do work and keep things going. That consumption comes with the cost of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, though. So, how can we use energy to keep the economy alive without burning out the planet in the process?

In a paper in PLOS ONE, University of Utah professor of atmospheric sciences Tim Garrett, with mathematician Matheus Grasselli of McMaster University and economist Stephen Keen of University College London, report that current world energy consumption is tied to unchangeable past economic production. And the way out of an ever-increasing rate of carbon emissions may not necessarily be ever-increasing energy efficiency -- in fact it may be the opposite.

"How do we achieve a steady-state economy where economic production exists, but does not continually increase our size and add to our energy demands?" Garrett says. "Can we survive only by repairing decay, simultaneously switching existing fossil infrastructure to a non-fossil appetite? Can we forget the flame?"

Thermoeconomics

Garrett is an atmospheric scientist. But he recognizes that atmospheric phenomena, including rising carbon dioxide levels and climate change, are tied to human economic activity. "Since we model the earth system as a physical system," he says, "I wondered whether we could model economic systems in a similar way."

He's not alone in thinking of economic systems in terms of physical laws. There's a field of study, in fact, called thermoeconomics. Just as thermodynamics describe how heat and entropy (disorder) flow through physical systems, thermoeconomics explores how matter, energy, entropy and information flow through human systems.

Many of these studies looked at correlations between energy consumption and current production, or gross domestic product. Garrett took a different approach; his concept of an economic system begins with the centuries-old idea of a heat engine. A heat engine consumes energy at high temperatures to do work and emits waste heat. But it only consumes. It doesn't grow.

Now envision a heat engine that, like an organism, uses energy to do work not just to sustain itself but also to grow. Due to past growth, it requires an ever-increasing amount of energy to maintain itself. For humans, the energy comes from food. Most goes to sustenance and a little to growth. And from childhood to adulthood our appetite grows. We eat more and exhale an ever-increasing amount of carbon dioxide.

"We looked at the economy as a whole to see if similar ideas could apply to describe our collective maintenance and growth," Garrett says. While societies consume energy to maintain day to day living, a small fraction of consumed energy goes to producing more and growing our civilization.

"We've been around for a while," he adds. "So it is an accumulation of this past production that has led to our current size, and our extraordinary collective energy demands and CO2 emissions today."

Growth as a symptom

To test this hypothesis, Garrett and his colleagues used economic data from 1980 to 2017 to quantify the relationship between past cumulative economic production and the current rate at which we consume energy. Regardless of the year examined, they found that every trillion inflation-adjusted year 2010 U.S. dollars of economic worldwide production corresponded with an enlarged civilization that required an additional 5.9 gigawatts of power production to sustain itself . In a fossil economy, that's equivalent to around 10 coal-fired power plants, Garrett says, leading to about 1.5 million tons of CO2 emitted to the atmosphere each year. Our current energy usage, then, is the natural consequence of our cumulative previous economic production.

They came to two surprising conclusions. First, although improving efficiency through innovation is a hallmark of efforts to reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, efficiency has the side effect of making it easier for civilization to grow and consume more.

Second, that the current rates of world population growth may not be the cause of rising rates of energy consumption, but a symptom of past efficiency gains.

"Advocates of energy efficiency for climate change mitigation may seem to have a reasonable point," Garrett says, "but their argument only works if civilization maintains a fixed size, which it doesn't. Instead, an efficient civilization is able to grow faster. It can more effectively use available energy resources to make more of everything, including people. Expansion of civilization accelerates rather than declines, and so do its energy demands and CO2 emissions."

A steady-state decarbonized future?

So what do those conclusions mean for the future, particularly in relation to climate change? We can't just stop consuming energy today any more than we can erase the past, Garrett says. "We have inertia. Pull the plug on energy consumption and civilization stops emitting but it also becomes worthless. I don't think we could accept such starvation."

But is it possible to undo the economic and technological progress that have brought civilization to this point? Can we, the species who harnessed the power of fire, now "forget the flame," in Garrett's words, and decrease efficient growth?

"It seems unlikely that we will forget our prior innovations, unless collapse is imposed upon us by resource depletion and environmental degradation," he says, "which, obviously, we hope to avoid."

So what kind of future, then, does Garrett's work envision? It's one in which the economy manages to hold at a steady state -- where the energy we use is devoted to maintaining our civilization and not expanding it.

It's also one where the energy of the future can't be based on fossil fuels. Those have to stay in the ground, he says.

"At current rates of growth, just to maintain carbon dioxide emissions at their current level will require rapidly constructing renewable and nuclear facilities, about one large power plant a day. And somehow it will have to be done without inadvertently supporting economic production as well, in such a way that fossil fuel demands also increase."

It's a "peculiar dance," he says, between eliminating the prior fossil-based innovations that accelerated civilization expansion, while innovating new non-fossil fuel technologies. Even if this steady-state economy were to be implemented immediately, stabilizing CO2 emissions, the pace of global warming would be slowed -- not eliminated. Atmospheric levels of CO2 would still reach double their pre-industrial level before equilibrating, the research found.

By looking at the global economy through a thermodynamic lens, Garrett acknowledges that there are unchangeable realities. Any form of an economy or civilization needs energy to do work and survive. The trick is balancing that with the climate consequences.

"Climate change and resource scarcity are defining challenges of this century," Garrett says. "We will not have a hope of surviving our predicament by ignoring physical laws."

Future work

This study marks the beginning of the collaboration between Garrett, Grasselli and Keen. They're now working to connect the results of this study with a full model for the economy, including a systematic investigation of the role of matter and energy in production.

"Tim made us focus on a pretty remarkable empirical relationship between energy consumption and cumulative economic output," Grasselli says. "We are now busy trying to understand what this means for models that include notions that are more familiar to economists, such as capital, investment and the always important question of monetary value and inflation."

Journal Reference:

Timothy J. Garrett, Matheus Grasselli, Stephen Keen. Past world economic production constrains current energy demands: Persistent scaling with implications for economic growth and climate change mitigation. PLOS ONE, 2020; 15 (8): e0237672 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237672

University of Utah. "Civilization may need to 'forget the flame' to reduce CO2 emissions." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 27 August 2020.

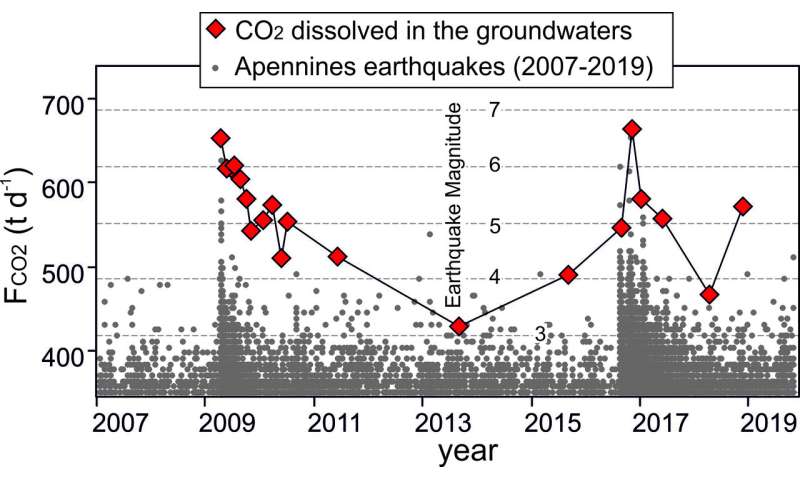

The amount of CO2 dissolved in groundwater is so large that, in some cases, strong free CO2 emissions are associated with the water discharges. The emission in the picture is located at San Vittorino plain (Rieti) about 30 km far from the epicenter of the April 2009 L’Aquila earthquake. Credit: Giovanni Chiodini - INGV (first author)

The amount of CO2 dissolved in groundwater is so large that, in some cases, strong free CO2 emissions are associated with the water discharges. The emission in the picture is located at San Vittorino plain (Rieti) about 30 km far from the epicenter of the April 2009 L’Aquila earthquake. Credit: Giovanni Chiodini - INGV (first author)