August 26, 2020 11.39pm EDT

Everyone is planning to return to the Moon. At least 10 missions by half a dozen nations are scheduled before the end of 2021, and that’s only the beginning.

Even though there are international treaties governing outer space, ambiguity remains about how individuals, nations and corporations can use lunar resources.

In all of this, the Moon is seen as an inert object with no value in its own right.

But should we treat this celestial object, which has been part of the culture of every hominin for millions of years, as just another resource?

The Moon Village Association public forum on August 18 debated whether the Moon should have legal personhood.

Why we should think about legal personhood

In April 2020, US president Donald Trump signed an Executive Order on the use of “off-Earth resources” which made clear his government’s stance towards mining on the Moon and other celestial bodies:

Americans should have the right to engage in commercial exploration, recovery, and use of resources in outer space.

Lunar resources include helium-3 (a possible clean energy source), rare earth elements (used in electronics) and water ice. Located in shadowed craters at the poles, water ice could be used to make fuel for lunar industries and to take the next step on to Mars.

As a thought experiment in how we might regulate lunar exploitation, some have asked whether the Moon should be granted legal personhood, which would give it the right to enter into contracts, own property, and sue other persons.

Read more: Five ethical questions for how we choose to use the Moon

Legal personhood is already extended to many non-human entities: certain rivers, deities in some parts of India, and corporations worldwide. Environmental features can’t speak for themselves, so trustees are appointed to act on their behalf, as is the case for the Whanganui River in New Zealand. One proposal is to apply the New Zealand model to the Moon.

Heritage and memory

As a space archaeologist, I study artefacts and places associated with space exploration in the 20th and 21st centuries. Previously, I worked with Indigenous communities to mitigate damage to heritage sites caused by mining. So I have a keen interest in what mining means for human heritage on the Moon.

Places like Tranquility Base, where humans first landed on the Moon in 1969, could be considered heritage for the entire species. There are more than 100 artefacts left at Tranquility Base, including a television camera, experiment packages, and Buzz Aldrin’s space boots.

The Apollo 11 Landing Module, with the Solar Wind Experiment and TV camera in the background. These artefacts were left on the surface on the Moon in 1969. NASA

Objects like this are full of meaning and memory. But these objects not just made by humans – they also shape human behaviour in their own right. It’s in this context that I want to consider two aspects of lunar personhood: memory and agency.

Can we support the legal concept of personhood for the Moon with actual features of personhood?

Does the Moon remember?

The 17th-century philosopher John Locke argued that memory was a key feature of personhood. It’s now acceptable to attribute memory to environmental features on Earth, like the oceans.

There are many different types of memory, of course – think of memory foam, a space-age spin-off with terrestrial applications.

One reason scientists want to study the Moon is to retrieve the memory of how it formed after separating from Earth billions of years ago.

This memory is encoded in geological features like craters and lava fields, and the regions at the lunar poles where shadows two billion years old preserve precious water ice.

Everyone is planning to return to the Moon. At least 10 missions by half a dozen nations are scheduled before the end of 2021, and that’s only the beginning.

Even though there are international treaties governing outer space, ambiguity remains about how individuals, nations and corporations can use lunar resources.

In all of this, the Moon is seen as an inert object with no value in its own right.

But should we treat this celestial object, which has been part of the culture of every hominin for millions of years, as just another resource?

The Moon Village Association public forum on August 18 debated whether the Moon should have legal personhood.

Why we should think about legal personhood

In April 2020, US president Donald Trump signed an Executive Order on the use of “off-Earth resources” which made clear his government’s stance towards mining on the Moon and other celestial bodies:

Americans should have the right to engage in commercial exploration, recovery, and use of resources in outer space.

Lunar resources include helium-3 (a possible clean energy source), rare earth elements (used in electronics) and water ice. Located in shadowed craters at the poles, water ice could be used to make fuel for lunar industries and to take the next step on to Mars.

As a thought experiment in how we might regulate lunar exploitation, some have asked whether the Moon should be granted legal personhood, which would give it the right to enter into contracts, own property, and sue other persons.

Read more: Five ethical questions for how we choose to use the Moon

Legal personhood is already extended to many non-human entities: certain rivers, deities in some parts of India, and corporations worldwide. Environmental features can’t speak for themselves, so trustees are appointed to act on their behalf, as is the case for the Whanganui River in New Zealand. One proposal is to apply the New Zealand model to the Moon.

Heritage and memory

As a space archaeologist, I study artefacts and places associated with space exploration in the 20th and 21st centuries. Previously, I worked with Indigenous communities to mitigate damage to heritage sites caused by mining. So I have a keen interest in what mining means for human heritage on the Moon.

Places like Tranquility Base, where humans first landed on the Moon in 1969, could be considered heritage for the entire species. There are more than 100 artefacts left at Tranquility Base, including a television camera, experiment packages, and Buzz Aldrin’s space boots.

The Apollo 11 Landing Module, with the Solar Wind Experiment and TV camera in the background. These artefacts were left on the surface on the Moon in 1969. NASA

Objects like this are full of meaning and memory. But these objects not just made by humans – they also shape human behaviour in their own right. It’s in this context that I want to consider two aspects of lunar personhood: memory and agency.

Can we support the legal concept of personhood for the Moon with actual features of personhood?

Does the Moon remember?

The 17th-century philosopher John Locke argued that memory was a key feature of personhood. It’s now acceptable to attribute memory to environmental features on Earth, like the oceans.

There are many different types of memory, of course – think of memory foam, a space-age spin-off with terrestrial applications.

One reason scientists want to study the Moon is to retrieve the memory of how it formed after separating from Earth billions of years ago.

This memory is encoded in geological features like craters and lava fields, and the regions at the lunar poles where shadows two billion years old preserve precious water ice.

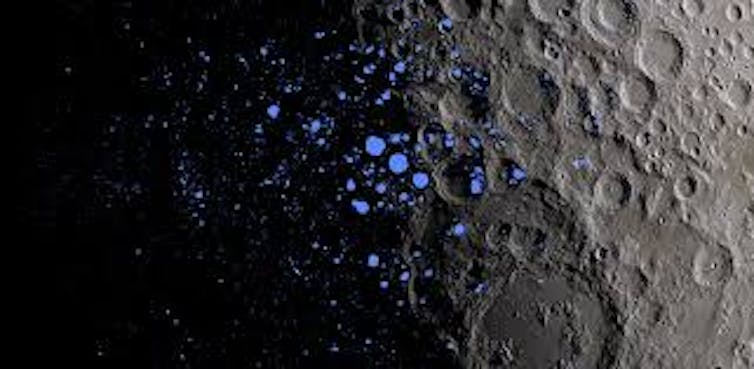

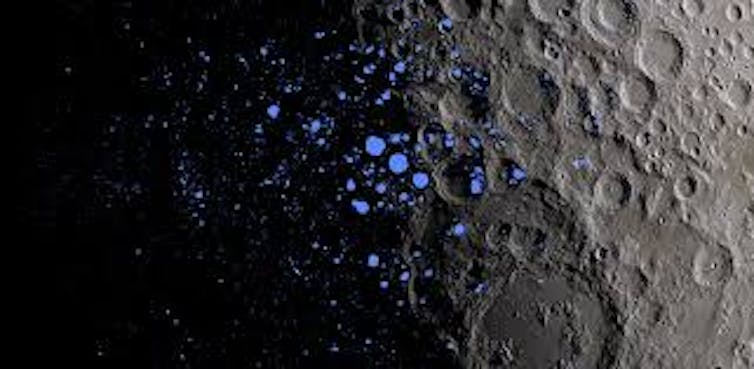

Permanently Shadowed Regions at the lunar South Pole in blue, captured by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. These unique regions only occur in two other locations in the solar system, Ceres and Mercury. NASA/GFSC

These are like archives storing information about past events. The most recent layer of memory records 60 years of human interventions, sitting lightly on the surface. This belongs to human heritage and memory, but it is now lunar memory too.

Read more: Friday essay: shadows on the Moon - a tale of ephemeral beauty, humans and hubris

These are like archives storing information about past events. The most recent layer of memory records 60 years of human interventions, sitting lightly on the surface. This belongs to human heritage and memory, but it is now lunar memory too.

Read more: Friday essay: shadows on the Moon - a tale of ephemeral beauty, humans and hubris

Does the Moon have agency?

The international Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) maintains the Planetary Protection Policy. This policy aims to prevent harm to potential life on other planets and moons. The Moon requires little protection because it is considered a dead world.

Recently, social media went wild with a story that self-described TikTok witches had hexed the Moon. More experienced WitchTokkers reacted with fury at their hubris in meddling with powers they didn’t understand.

Despite its apparent irrationality, there was something delightful about this story. It showed how the Moon is thought to interact with human life on its own terms. The “witches” took the Moon seriously as an agent in human affairs.

When humans return to the Moon, they will not find it a dead world. It is a very active landscape shaped by dust, shadows and light.

The Moon reacts to human disturbance by mobilising dust that irritates lungs, breaks down seals and prevents equipment from working. This is neither passive nor hostile – just the Moon being itself.

The Moon as an equal partner

Australian philosopher Val Plumwood would see the Moon as a co-participant in human affairs, rather than formless, dead matter:

When the other’s agency is treated as background or denied, we give the other less credit than it is due. We can easily come to take for granted what they provide for us, and to starve them of the resources they need to survive.

So this leaves me with a question: if the Moon is a legal person, what does it need from us to sustain its memory and agency? How can we achieve what Plumwood calls a “mutual flourishing”?

The answers might lie in our attitudes.

We could abandon the idea that our moral obligations only cover living ecologies. We should consider the Moon as an entity beyond the resources it might hold for humans to use.

In practice, this might mean trustees would determine how much of the water ice deposits or other geological features can be used, or set conditions on activities which alter the qualities of the Moon irreversibly.

The record of human activities we leave on the Moon should reflect respect, as we are contributing to what it remembers. In this sense, the TikTok witches had the right idea.

This article is based on a presentation at a Moon Village Association public forum organised by the Office of Other Spaces, Catapult UK and the Space Junk Podcast, and supported by Inspiring NSW and the Hunter Innovation and Science Hub.

Author

Alice Gorman

Alice Gorman is a Friend of The Conversation.

Associate Professor in Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University

Disclosure statement

Alice Gorman is a member of the Moon Village Association, For All Moonkind, and the Advisory Council of the Space Industry Association of Australia.

Partners

Flinders University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

You might also like

The Moon and stars are a compass for nocturnal animals – but light pollution is leading them astray

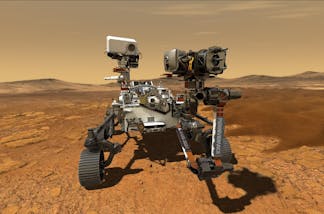

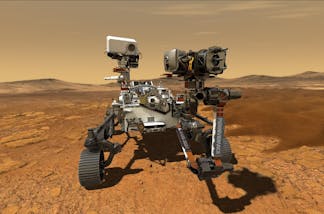

Mars 2020: the hunt for life on the red planet is about to get serious

SpaceX: Crew Dragon is returning to Earth – here’s when to hold your breath

Perseverance: the Mars rover searching for ancient life, and the Aussie scientists who helped build it

Copyright © 2010–2020, Academic Journalism Society

Alice Gorman is a Friend of The Conversation.

Associate Professor in Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University

Disclosure statement

Alice Gorman is a member of the Moon Village Association, For All Moonkind, and the Advisory Council of the Space Industry Association of Australia.

Partners

Flinders University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

You might also like

The Moon and stars are a compass for nocturnal animals – but light pollution is leading them astray

Mars 2020: the hunt for life on the red planet is about to get serious

SpaceX: Crew Dragon is returning to Earth – here’s when to hold your breath

Perseverance: the Mars rover searching for ancient life, and the Aussie scientists who helped build it

Copyright © 2010–2020, Academic Journalism Society