What’s behind the new push for unionization by journalists

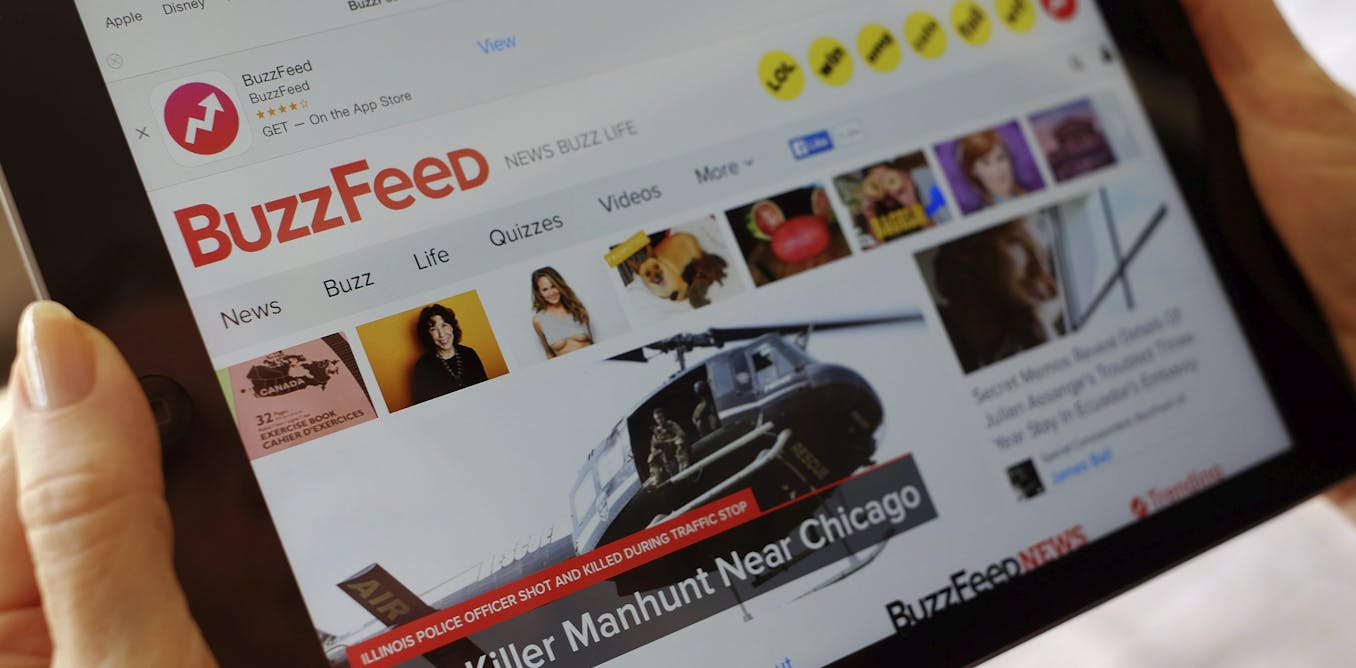

Digital news organizations like Buzzfeed and Vox are among those where journalists are unionizing. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel, File)

August 31, 2020 10.58am EDT

As Labour Day approaches, consider who’s making the news. From essential workers to gig workers and those working from home, the COVID-19 pandemic has put labour issues on journalists’ agendas.

At the same time, journalists are increasingly viewing themselves as “workers first” and forming unions to address longstanding issues in their industry.

By our count, since 2015, journalists have unionized at more than 80 digital and legacy media outlets, including at BuzzFeed, VICE Canada, Vox, Canadaland and 28 brands owned by the conglomerate Hearst Magazines.

Back to the future?

Journalists’ unions are nothing new. In the 1930s, newspaper journalists unionized to protect editorial independence and collectively negotiate working conditions. By the 2000s, legacy media unions faced big challenges: traditional newsrooms were being gutted by layoffs. And digital successors, with their tech start-up feel, seemed to be culturally off-limits to unions.

So it was surprising when staff at New York-based Gawker announced in the spring of 2015 it was unionizing, kicking off a wave of unionization in digital media. Since then, thousands of new members have joined The NewsGuild, the Writers Guild of America, East and the Communication Workers of America Canada.

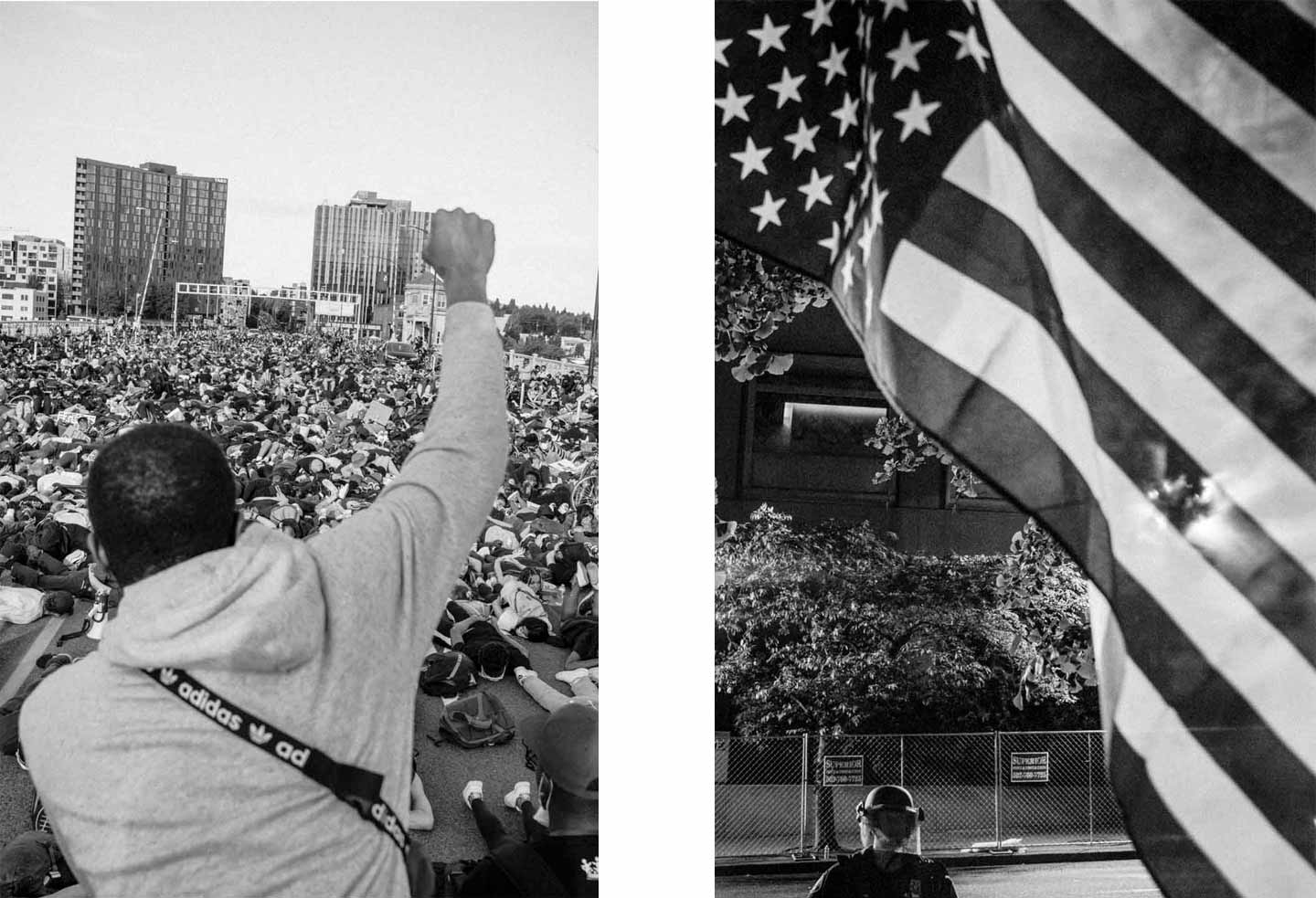

Organizing has not let up amid the pandemic. The economic fallout from COVID-19 and the demands for racial justice elevated by protests against anti-Black racism give the media union movement renewed cause.

To understand why and how journalists are unionizing, we interviewed 50 media workers and union staff involved in this organizing push for our book, New Media Unions. Three themes emerged that persist as journalists continue to organize.

Protection and voice

Journalists organized to improve their livelihoods, including low pay and precarious employment. Unionizing enables media workers to negotiate legally binding collective bargaining agreements with employers. Contracts have raised labour standards, introducing salary minimums, increased benefits and a process for converting freelancers to full-time employees, for example.

Less than two months into the pandemic, 36,000 U.S. news workers had lost their jobs, been temporarily laid off or had their pay cut, according to The New York Times. Although news sites’ traffic soared as an anxious public sought information about the health crisis, companies’ ad revenue plunged and many outlets closed.

In hindsight, unionizing was a form of emergency preparedness. Before the pandemic, journalists acted to protect their livelihoods in a volatile industry where closures and cuts were commonplace. Severance packages became a bargaining priority. As union drives continue to launch, the pandemic has not diminished journalists’ resolve to build a safety net.

Journalists are unionizing to protect journalism, too. Contracts strengthen divisions between editorial and marketing departments, for example. And as local outlets are bought up by cost-cutting private equity firms, staff are organizing not just to preserve jobs but also local news, whose role as an essential service has been reaffirmed during the pandemic.

Having a formal mechanism to negotiate with management has given many journalists a say in how their employers respond to the pandemic. The L.A. Times Guild proposed pay cuts rather than layoffs, for example, which the Buzzfeed News Union used as a model to save jobs in their newsroom.

Diversity and equity

Racial and gender divides have also been an impetus to organize. Journalists we interviewed classified their workplaces on a narrow diversity spectrum, from “pretty white” to “mostly white” to “overwhelmingly white.”

Journalists are unionizing to change this composition to better reflect the communities they cover. Strategies including reforming informal recruitment practices — hiring from editors’ existing networks, for example — that perpetuate the industry’s homogeneity.

Research and first-person accounts show that women and especially racialized journalists are undervalued and often unable to sustain media careers. Journalists organized for pay equity and have negotiated contracts with salary scales by job title, which close pay gaps.

Beyond contract language that addresses discrimination and harassment, new media unions have negotiated the creation of union-management committees, formal channels where workers can push companies on equity, including retention and promotion of racialized journalists.

When Black Lives Matter protests intensified this summer, journalists’ struggles for racial justice went public. Journalists at the Los Angeles Times, for example, have pressured management to hire more racialized journalists and used the #BlackatLAT hashtag to document the mistreatment of Black journalists.

And after the The New York Times published an op-ed that called for a military response to Black Lives Matter protests, staffers organized a public response, tweeting: “Running this puts Black @nytimes staff in danger.” It led to the resignation of a senior editor.

Care and solidarity

The new media union movement has prioritized an ethic of care. Journalists care deeply about the work that they do, and statements announcing union drives declare workers’ commitment to producing journalism for their communities.

Drives have also been based on friendship.

Many union drives stemmed from friends in newsroom discussing disparities. (Piqsels)

Many campaigns emerged from friends in newsrooms discussing working conditions. They expanded as journalists in secure positions learned that colleagues were paid less for doing the same work, or were unable to pay rent or access health care. Organizing involves making deep personal connections as journalists have one-on-one discussions about problems at work and what a union could achieve.

As journalists were laid off during the pandemic, this care translated into union members setting up relief funds. The Florida Times-Union Guild, for example, has raised more than $15,000 for colleagues in need.

Organizing can blunt the competitive nature of journalism. Workers at outlets that compete for readers now share organizing and bargaining strategies and support union drives with tweets of solidarity. Unions also amplify journalists’ voices in the discussions of wider policy responses to the media crisis, as illustrated by the NewsGuild’s Save the News campaign.

For several journalists we spoke to, union organizing is a way to care for oneself in a job that can take a toll. As one journalist told us:

“Organizing has been good for my mental health. A lot of the time, we as journalists look at the state of the world and get very depressed. One of the cures for me has been to stand up for our newsroom and for other newsrooms. It has given me renewed hope in the industry.”

Unionizing will not fix all the problems facing journalism. But a union remains journalists’ best collective tool to sustain media workers in times of crisis and beyond.

Authors

Nicole Cohen

Associate Professor, Communication, University of Toronto

Greig de Peuter

Associate Professor of Communication Studies, Wilfrid Laurier University

Disclosure statement

Nicole Cohen receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Greig de Peuter receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Partners