He helped galvanise the US civil rights movement, and today sparks intense debate about cultural dominance and the musical canon. In his 250th anniversary year can we listen to Beethoven and what he represents with fresh ears?

Philip Clark

Mon 7 Sep 2020 11.47 BST

Exactly 80 years after Beethoven’s death, in 1907, the British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor began speculating that Beethoven was black. Colderidge-Taylor was mixed race – with a white English mother and a Sierra Leonean father - and said that he couldn’t help noticing remarkable likenesses between his own facial features and images of Beethoven’s. Having recently returned from the segregated US, Coleridge-Taylor projected his experiences there onto the German composer. “If the greatest of all musicians were alive today, he would find it impossible to obtain hotel accommodation in certain American cities.”

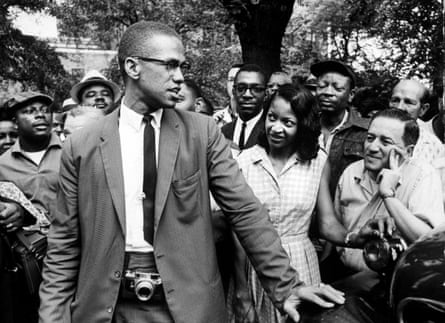

His words would prove prophetic. During the 1960s, the mantra “Beethoven was black” became part of the struggle for civil rights. By then Coleridge-Taylor had been dead for 50 years and was all but forgotten, but as campaigner Stokely Carmichael raged against the deeply ingrained assumption that white European culture was inherently superior to black culture, the baton was passed. “Beethoven was as black as you and I,” he told a mainly black audience in Seattle, “but they don’t tell us that.” A few years earlier, Malcolm X had given voice to that same idea when he told an interviewer that Beethoven’s father had been “one of the blackamoors that hired themselves out in Europe as professional soldiers”.

“Beethoven was black” became a refrain chanted on a San Francisco soul music radio station and, in 1969, hit mass consciousness when Rolling Stone magazine ran a story headlined: “Beethoven was black and proud!” In 1988, two white students at Stanford University in California, following a heated discussion about music and race, defaced a poster of Beethoven, giving him crude stereotypical African American features, an act reported in the press as an act of racism.

Beethoven: where to start with his music

Read more

Itchiness about Beethoven’s cultural dominance would continue to bring classical music out in occasional hives, and in 2007 Nadine Gordimer published a collection of short stories called Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black. But the issue of race laid largely dormant until this year – the 250th anniversary of his birth – when against the backdrop of Covid-19 becoming inextricably linked with the Black Lives Matter movement, echoes of Carmichael and X were voiced, coming from directions nobody expected.

William Gibbons, a musicologist at the College of Fine Arts in Forth Worth, Texas, had already put a bomb under classical music Twitter with a thread that began: “As 2019 winds down, here’s a short thread about one of my big resolutions for 2020: spending a full year avoiding Beethoven.” Then the pandemic struck and swept all the Beethoven celebrations aside anyway. With Europe heading towards lockdown, the composer Charlotte Seither, debating at the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, caused a stir when she spoke of Beethoven fatigue and of his “toxic cult of genius” and “thinking in categories of dominance”. Andrea Moore – assistant professor of music at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts – writing in the Chicago Tribune, called for a “year-long moratorium” on Beethoven performances. His music is ubiquitous, she reasoned – so how about using the “Beethoven-sized hole” left to commission new music, then return to the composer with fresh ears in 12 months’ time?

Malcolm X at a civil rights demonstration in 1963. Photograph: Bob Henriques/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image

Malcolm X at a civil rights demonstration in 1963. Photograph: Bob Henriques/Time & Life Pictures/Getty ImageMoore’s proposal would end positively at least: we get Beethoven back, plus a stack of new compositions. But the truth is Beethoven is like Michael Rosen’s bear hunt – you can’t go over him, you can’t go under him, you have to go through him. Academics manufacturing a culture war, in which there can be no winners, is a very 21st-century way of dealing with a figure perceived as a problem: you turn him into a straw man and complain about being triggered. Carmichael and Malcolm X were far wiser. They didn’t advocate cancelling Beethoven, nor did they deal in easy gesture politics – the stakes were too high.

Was Beethoven black? The evidence is scant and inconclusive. The case rests on two possibilities: that Beethoven’s Flemish ancestors married Spanish “blackamoors” of African descent, or that Beethoven’s mother had an affair. But the truth Carmichael and Malcolm X sought was not scientific. “Beethoven was black” was a grand metaphor designed to unsettle and shake certainty.

Had Beethoven been black, would he have been classed as a canonical composer? And what about other black composers lost in history?

Metaphors ran right through black music. Edward Ellington and William Basie were ennobled to the status of a Duke and a Count, and the most intricate metaphor of all was spun by the Alabama-born bandleader Herman Blount who had begun to perform as Sun Ra. Blount – like Malcolm X, originally Malcolm Little – rejected his given surname as a “slave name”, and created an elaborate metaphorical backstory about Sun Ra, an alien from Saturn, who descended to Earth to preach peace and togetherness.

Corey Mwamba – musician, researcher and presenter of BBC Radio 3’s contemporary jazz programme Freeness – thinks that the metaphor has retained its potency. “The statement ‘Beethoven was black’ was a disruption of a very canonical way of thinking,” he tells me. “It makes us think again about a culture that gives his music so much visibility. Had Beethoven been black, would he have been classed as a canonical composer? And what about other black composers lost in history?”

Among many black composers whose work has disappeared from history, the story of Julius Eastman is perhaps most telling. As composer, singer and pianist Eastman was a vital part of the 1960s and 70s New York music scene, his open-form scores fusing the loops of minimalism with the grooves of popular music – a volatile synthesis that often detonated into free improvisation. Before his death on the streets and homeless in 1990, he loaded his pieces with deliberately provocative titles that pushed the spirit of “Beethoven was black” from slogan towards something that actually happened in sound.

In his recent book, A Hidden Landscape Once a Week, Mark Sinker reported his conversation with the photographer and writer, Val Wilmer, about when she interviewed Steve Reich, who had recently completed his landmark piece Drumming, based on drum patterns he heard in Ghana. Talking about an African American musician of mutual acquaintance, Reich said “he’s one of the only blacks you can talk to,” before adding “blacks are getting ridiculous in the States now”. Wilmer was shocked and enraged. “Wouldn’t you become politicised?” she concluded. The wider pressures on black composers in 1970s America can never be doubted.

“Radicals like James Baldwin and Angela Davis took time to think about what they were doing, then produced change,” Mwamba adds, “We actually need a deeper understanding of Beethoven, to understand why we love this music. It’s important we present this music from a position of love, rather than hierarchy or power, or as ‘something we’ve always done’.”

•The Aurora Orchestra perform Beethoven’s 7th symphony at the Proms on Radio 3 and BBC4 on 10 September alongside the world premiere of Richard Ayres’ No. 52 (Three pieces about Ludwig van Beethoven, dreaming, hearing loss, and saying goodbye)

Image:An artist's impression of Assange in the dock at the Old Bailey on Monday

Image:An artist's impression of Assange in the dock at the Old Bailey on Monday