Sea ice triggered the Little Ice Age, finds a new study

by University of Colorado at Boulder

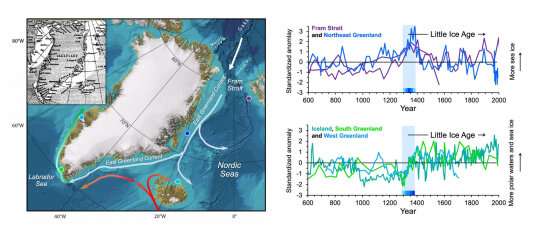

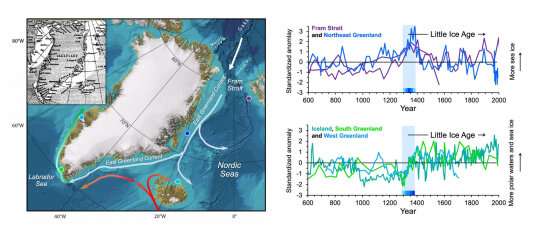

The map shows Greenland and adjacent ocean currents. Colored circles show where some of the sediment cores used in the study were obtained from the seafloor. The small historical map from the beginning of the 20th century shows the distribution of Storis, or sea ice from the Arctic Ocean, which flows down the east coast of Greenland. The graphs show the reconstructed time series of changes in the occurrence of sea ice and polar waters in the past. The colors of the curves correspond to the locations on the map. The blue shading represents the period of increased sea ice in the 1300s. Credit: The figures are modified from Miles et al., 2020.

A new study finds a trigger for the Little Ice Age that cooled Europe from the 1300s through mid-1800s, and supports surprising model results suggesting that under the right conditions sudden climate changes can occur spontaneously, without external forcing.

The study, published in Science Advances, reports a comprehensive reconstruction of sea ice transported from the Arctic Ocean through the Fram Strait, by Greenland, and into the North Atlantic Ocean over the last 1400 years. The reconstruction suggests that the Little Ice Age—which was not a true ice age but a regional cooling centered on Europe—was triggered by an exceptionally large outflow of sea ice from the Arctic Ocean into the North Atlantic in the 1300s.

While previous experiments using numerical climate models showed that increased sea ice was necessary to explain long-lasting climate anomalies like the Little Ice Age, physical evidence was missing. This study digs into the geological record for confirmation of model results.

Researchers pulled together records from marine sediment cores drilled from the ocean floor from the Arctic Ocean to the North Atlantic to get a detailed look at sea ice throughout the region over the last 1400 years.

"We decided to put together different strands of evidence to try to reconstruct spatially and temporally what the sea ice was during the past one and a half thousand years, and then just see what we found," said Martin Miles, an INSTAAR researcher who also holds an appointment with NORCE Norwegian Research Centre and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research in Norway.

The cores included compounds produced by algae that live in sea ice, the shells of single-celled organisms that live in different water temperatures, and debris that sea ice picks up and transports over long distances. The cores were detailed enough to detect abrupt (decadal scale) changes in sea ice and ocean conditions over time.

The records indicate an abrupt increase in Arctic sea ice exported to the North Atlantic starting around 1300, peaking in midcentury, and ending abruptly in the late 1300s.

"I've always been fascinated by not just looking at sea ice as a passive indicator of climate change, but how it interacts with or could actually lead to changes in the climate system on long timescales," said Miles. "And the perfect example of that could be the Little Ice Age."

"This specific investigation was inspired by an INSTAAR colleague, Giff Miller, as well as by some of the paleoclimate reconstructions of my INSTAAR colleagues Anne Jennings, John Andrews, and Astrid Ogilvie," added Miles. Miller authored the first paper to suggest that sea ice played an essential role in sustaining the Little Ice Age.

Scientists have argued about the causes of the Little Ice Age for decades, with many suggesting that explosive volcanic eruptions must be essential for initiating the cooling period and allowing it to persist over centuries. One the hand, the new reconstruction provides robust evidence of a massive sea-ice anomaly that could have been triggered by increased explosive volcanism. One the other hand, the same evidence supports an intriguing alternate explanation.

Climate models called "control models" are run to understand how the climate system works through time without being influenced by outside forces like volcanic activity or greenhouse gas emissions. A set of recent control model experiments included results that portrayed sudden cold events that lasted several decades. The model results seemed too extreme to be realistic—so-called Ugly Duckling simulations—and researchers were concerned that they were showing problems with the models.

Miles' study found that there may be nothing wrong with those models at all.

"We actually find that number one, we do have physical, geological evidence that these several decade-long cold sea ice excursions in the same region can, in fact do, occur," he said. In the case of the Little Ice Age, "what we reconstructed in space and time was strikingly similar to the development in an Ugly Duckling model simulation, in which a spontaneous cold event lasted about a century. It involved unusual winds, sea ice export, and a lot more ice east of Greenland, just as we found in here." The provocative results show that external forcing from volcanoes or other causes may not be necessary for large swings in climate to occur. Miles continued, "These results strongly suggest...that these things can occur out of the blue due to internal variability in the climate system."

The marine cores also show a sustained, far-flung pulse of sea ice near the Norse colonies on Greenland coincident with their disappearance in the 15th century. A debate has raged over why the colonies vanished, usually agreeing only that a cooling climate pushed hard on their resilience. Miles and his colleagues would like to factor in the oceanic changes nearby: very large amounts of sea ice and cold polar waters, year after year for nearly a century.

"This massive belt of ice that comes streaming out of the Arctic—in the past and even today—goes all the way around Cape Farewell to around where these colonies were," Miles said. He would like to look more closely into oceanic conditions along with researchers who study the social sciences in relation to climate.

Explore further Increasing Arctic freshwater is driven by climate change

Race to rescue animals as Brazilian wetlands burn

by Eugenia Logiuratto

An injured jaguar sits on the bank of a river in the Panatal, the Brazlian tropical wetlands hit by massive fires

Wildlife guide Eduarda Fernandes steers a speedboat up the Piquiri river in western Brazil, scanning the horizon for jaguars wounded in the wildfires ripping through the Pantanal, the world's biggest tropical wetlands.

Fernandes, 20, is part of a team of volunteers working to find and rescue jaguars wounded by the record-breaking blazes, which have burned through nearly 12 percent of the Pantanal.

"Our goal is to reduce the impact of the fires as much as we can, by leaving food and water for the animals and rescuing the wounded ones," she said.

The state park where she and her team are working, Encontro das Aguas, is known for having the largest jaguar population on Earth.

In normal times, it is home to at least 150 jaguars, a species classified as "near threatened" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature because of its declining numbers.

But now the fires have burned through 85 percent of the 109,000-hectare (270,000-acre) park, and many of the jaguars have disappeared.

No one knows if they are dead, wounded or have fled elsewhere.

Jaguar trapping 101

After a two hours searching by boat, the team finds a male jaguar resting on the river bank beneath a tree hanging with vines, his spots standing out against a pile of leaves left dry by the region's worst drought in decades.

Rescuers monitor an injured jaguar in the Panatal, he world's biggest tropical wetlands

They photograph it and evaluate from afar: the jaguar has an injured front paw that may need treatment.

Capturing a jaguar is no small feat. It takes tranquilizer darts, at least three boats and a lot of force.

The tranquilizer takes about 10 minutes to kick in, and during that lapse jaguars have been known to try to swim away.

They are excellent swimmers, but risk drowning when the drug takes effect.

"Everything can go wrong," said veterinarian Jorge Salomao of the charity Ampara Animal (Animal Support).

As the team assesses the situation, sweating in the hot sun and surrounded by semi-scorched vegetation, the jaguar gets up to drink from the river.

That gives the veterinarians a chance to make a more precise diagnosis: he is walking gingerly, but does not appear to be in acute pain.

"He can probably recover on his own. Better to stand down" from capturing him, said Salomao.

He will return in a few days to see how the big cat is doing.

Volunteers look for an injured jaguar in the Pantanal, a region famous for its wildlife

Animal rescue specialists

Another team is in a four-by-four traveling the dusty highway across the Pantanal, the Transpantaneira, setting out water and food for animals whose habitats have been destroyed in the fires.

These volunteers are from the Disaster Rescue Group for Animals (GRAD), which specializes in helping animals hit by man-made or natural disasters.

"The fires are a huge problem in and of themselves, but after that, the animals are left facing hunger and thirst," said veterinary student Enderson Barreto, 22, using thick gloves and shin guards to protect himself from being bitten by one of the region's many poisonous snakes.

Veterinarian Luciana Guimaraes is holding a small howler monkey that was hit by a car on the road.

"That's going to be happening a lot, because they approach the road looking for food and water," said the 41-year-old wildlife specialist.

Having traveled from Sao Paulo to volunteer here, she is trying to hold onto hope.

"Nature has a great capacity for recovery, even in a situation like this, where everything seems to have burned," she said.

"But it can take a very long time."

Explore further Battle on to save Brazil's tropical wetlands from flames

© 2020 AFP

Coffee associated with improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients

by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

In a large group of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, consumption of a few cups of coffee a day was associated with longer survival and a lower risk of the cancer worsening, researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and other organizations report in a new study.

The findings, based on data from a large observational study nested in a clinical trial, are in line with earlier studies showing a connection between regular coffee consumption and improved outcomes in patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer. The study is being published today by JAMA Oncology.

The investigators found that in 1,171 patients treated for metastatic colorectal cancer, those who reported drinking two to three cups of coffee a day were likely to live longer overall, and had a longer time before their disease worsened, than those who didn't drink coffee. Participants who drank larger amounts of coffee—more than four cups a day—had an even greater benefit in these measures. The benefits held for both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee.

The findings enabled investigators to establish an association, but not a cause-and-effect relationship, between coffee drinking and reduced risk of cancer progression and death among study participants. As a result, the study doesn't provide sufficient grounds for recommending, at this point, that people with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer start drinking coffee on a daily basis or increase their consumption of the drink, researchers say.

"It's known that several compounds in coffee have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and other properties that may be active against cancer," says Dana-Farber's Chen Yuan, ScD, the co-first author of the study with Christopher Mackintosh, MLA, of the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine. "Epidemiological studies have found that higher coffee intake was associated with improved survival in patients with stage 3 colon cancer, but the relationship between coffee consumption and survival in patients with metastatic forms of the disease hasn't been known."

The new study drew on data from the Alliance/SWOG 80405 study, a phase III clinical trial comparing the addition of the drugs cetuximab and/or bevacizumab to standard chemotherapy in patients with previously untreated, locally advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer. As part of the trial, participants reported their dietary intake, including coffee consumption, on a questionnaire at the time of enrollment. Researchers correlated this data with information on the course of the cancer after treatment.

They found that participants who drank two to three cups of coffee per day had a reduced hazard for death and for cancer progression compared to those who didn't drink coffee. (Hazard is a measure of risk.) Those who consumed more than four cups per day had an even greater benefit.

"Although it is premature to recommend a high intake of coffee as a potential treatment for colorectal cancer, our study suggests that drinking coffee is not harmful and may potentially be beneficial," says Dana-Farber's Kimmie Ng, MD, MPH, senior author of the study.

"This study adds to the large body of literature supporting the importance of diet and other modifiable factors in the treatment of patients with colorectal cancer," Ng adds. "Further research is needed to determine if there is indeed a causal connection between coffee consumption and improved outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer, and precisely which compounds within coffee are responsible for this benefit."

Explore further

Do-it-yourself COVID-19 vaccines fraught with public health problems

by University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

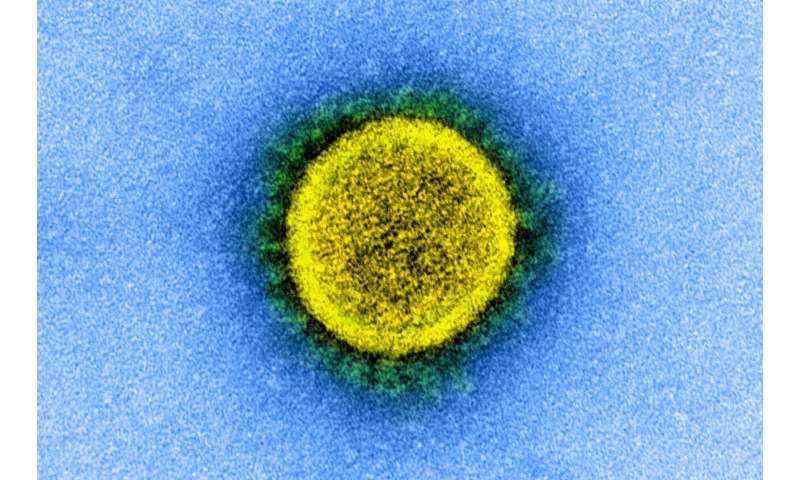

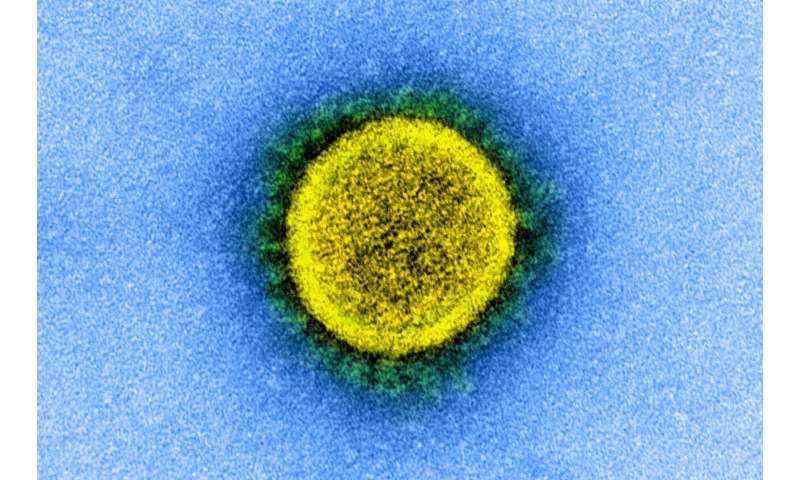

SARS-CoV-2 (shown here in an electron microscopy image). Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Well-intentioned "citizen scientists" developing homemade COVID-19 vaccines may believe they're inoculating themselves against the ongoing pandemic, but the practice of self-experimentation with do-it-yourself medical innovations is fraught with important legal, ethical and public health issues, according to a new paper in the journal Science co-written by a University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign legal expert who studies the policy implications of advanced biotechnologies.

As the novel coronavirus pandemic continues to ravage the globe, several citizen science groups outside the auspices of the pharmaceutical industry have been working to develop and self-test unproven medical interventions to combat COVID-19. Although some of the interest in a DIY approach stems from the idea that self-experimentation can't be regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other public health authorities, that belief is legally and factually incorrect, said Jacob S. Sherkow, a professor of law at Illinois.

"Citizen science" broadly describes activities having a scientific aim that invite public participation. While citizen science is important and has a strong tradition in the U.S., "a homemade COVID-19 vaccine is perhaps more dangerous than people would like to believe," Sherkow said.

"We're all sympathetic to the notion that people want to inoculate themselves against the virus," he said. "But people need to understand that every home remedy is not necessarily going to help, and some may very well be fatal."

The interest in a do-it-yourself approach stems from a mistaken belief that self-experimentation wouldn't be subject to laborious ethics board review or federal regulation. But that misunderstanding has potentially dire public health implications, said Sherkow, also an affiliate of the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology.

"People should be aware that just because they're experimenting on themselves doesn't make it legal without approval," he said. "Some self-experimentation can qualify as human subjects research that is required to undergo ethics review, by law or institutional policy. Just because it's self-experimentation doesn't give you carte blanche."

Similarly, simply publishing medical information on the internet is, generally speaking, not regulated by the FDA. But developing a possible therapeutic product using typical equipment, chemicals and reagents would likely be regulable by the FDA, Sherkow said.

"Taking information that you found in some dark corner of the internet but using it to develop your own materials and needing to ship materials or reagents across state lines—that is interstate commerce and is what triggers FDA oversight," he said. "At that point, that's essentially where the FDA can stop you."

Homemade interventions exist in stark contrast to traditional paths to vaccine development, which require randomized controlled trials with well-defined endpoints, such as demonstrated immune responses, and protocols concerning the retention and use of data. Biohackers creating and self-administering unapproved and unproven medical interventions run the risk of not only endangering public health, but also undermining public trust in all vaccines, Sherkow said.

"We're living in an age of vaccine disinformation," he said. "It's one of the reasons why we have phased clinical trials for the development of vaccines and medical treatments. It's not just a matter of figuring out whether something is effective or whether it works. It's also a matter of figuring out the gross toxicity of the treatment, and if it's been manufactured in such a way so that it's not going to harm people."

Characterizing or positioning research as self-experimentation does not eliminate risks to bystanders or the collective good.

Citizen scientists, especially those professional scientists moonlighting as homemade vaccine makers, "must take their heightened ethical responsibilities seriously when promoting DIY interventions or treatments, especially those with potentially serious public health and societal effects," Sherkow said.

"Although many citizen scientists appear to take seriously the ethical responsibilities associated with their activities, it is important to recognize that those responsibilities expand when public health is at stake, such as with COVID-19 vaccine development," he said. "But just because there's a list of instructions on the internet created by a lot of well-respected and well-trained scientists doesn't mean that something can't go wrong."

Explore further Follow the latest news on the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak

Hospitals miss mental illness diagnosis in more than a quarter of patients

by University College London

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Severe mental illness diagnoses are missed by clinicians in more than one quarter of cases when people are hospitalised for other conditions, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

People from ethnic minority groups are even more likely to have previously diagnosed mental illnesses go unnoticed by medical staff, according to the findings from hospitals in England, published in PLOS Medicine.

However, researchers found the situation is improving, as data from 2006 showed that severe mental illness diagnoses were missed in more than half of cases.

Corresponding author, Hassan Mansour (UCL Psychiatry), who led the study as part of his MSc, said: "When someone is admitted to hospital, it's important that the medical staff are aware of their other conditions, as these might affect what treatments are best for them, in order to provide holistic care.

"We found encouraging signs that clinicians are more frequently identifying severe mental illnesses in hospital patients than they were a decade ago, but there's a lot more that can be done, particularly to address disparities between ethnic groups, to ensure that everyone gets the best care available."

The large cohort study involved 13,786 adults who had diagnoses of severe mental illnesses, which included bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, from 2006 to 2017. They linked the data to 45,706 emergency hospital admissions for the same people over the same period, to see whether their previously-diagnosed mental illness was recorded when they were admitted to hospital for a physical health issue.

Across the whole study period, mental illnesses were recorded at hospitalisation 70% of the time, after a prior diagnosis. This figure rose from 48% in 2006 to 75% in 2017.

The researchers say the improvements over time may be due to NHS commitments towards whole person-centred care, financial incentives, improvements in coding practices, or expansions of liaison psychiatric services in hospitals.

Not all of the recordings included the specific diagnosis, as the figures include any recording of a psychiatric illness. Specific recording of schizophrenia occurred in only 56% of people with this condition and, for bipolar disorder, the specific condition was recorded in only 50%, meaning that conditions may be mis-diagnosed as another, possibly less severe, mental illness.

The researchers found that people from ethnic minority backgrounds were more likely to have missed diagnoses, particularly those from Black African or Caribbean backgrounds who were 38% more likely to have their diagnosis unrecorded compared to those from white ethnic backgrounds. The researchers say this may have been due to clinicians being less able to detect these conditions in people from other ethnic and cultural groups, or perhaps language barriers, or stigma felt by patients.

Hassan Mansour said: "The disparities we found between ethnic groups are concerning because previous studies have identified particularly poor health outcomes for people from minority ethnic groups with severe mental illnesses. Training in culturally-sensitive diagnosis may be needed to reduce inequalities in medical care."

Doctors also missed diagnoses more frequently for married people, which the researchers say could be due to stigma, if spouses providing information to hospital staff are reluctant to mention a mental illness diagnosis, or are unaware of it.

Co-author Dr. Christoph Mueller (King's College London Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust) said: "Knowing that a patient has a severe mental illness can be important for their treatment, as they might benefit from additional support after being discharged, and they may also need to continue taking their psychiatric medications, or even make changes to these, while in hospital."

Senior author Dr. Andrew Sommerlad (UCL Psychiatry and Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust) said: "If someone with a severe mental illness comes to hospital physically unwell, it might be an indicator that their mental health is getting worse. It could be a critical time to identify issues with mental and physical health, and an opportunity to access support for their mental illness."

The researchers are calling for better sharing of data between health services.

Dr. Sommerlad said: "It's important to understand that physical and mental health are interlinked, and should not be seen as separate entities. Both can impact the other, so more needs to be done to bridge the gap and achieve truly integrated care that's accessible to everyone."

Explore further Hospitals often missing dementia despite prior diagnosis

Tweets show vapers rarely use e-cigarettes to quit smoking or improve health

by Doug Dollemore, University of Utah Health Sciences

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

The vast majority of Twitter users who vape with JUUL e-cigarettes are not using the devices to stop smoking or to improve their health, according to a research team led by University of Utah Health scientists. The researchers say this finding, which challenges JUUL's stated mission of improving smokers' lives, could help hone anti-smoking and vaping efforts targeted at Twitter users, particularly underage teens.

Based on their manual analysis of more than 4,000 tweets, the scientists concluded that only 1% of Twitter users mentioned JUUL as a smoking cessation method and scarcely 7% referred to any potential health benefits of using the vaping devices.

The study, which was conducted in conjunction with the University of Washington School of Medicine and the University of California, San Diego, appears in the Journal of Medical Internet Research—Public Health & Surveillance.

"Some people thought that my generation was going to end smoking," says Ryzen Benson, lead author of the study and a graduate student in the U of U Health Department of Biomedical Informatics. "For a while, we did see a large decline in smoking among teens and younger adults. But then JUUL and other electronic nicotine delivery systems became popular."

"This emergence is reflected in what we found being posted on Twitter," Benson says. "Based on what we saw in people's tweets, they are clearly not using JUUL as a smoking cessation tool or as a healthier alternative to traditional cigarettes."

Use of e-cigarettes—devices that heat liquid to produce a vapor that users inhale into their lungs—has skyrocketed since they were first introduced in 2007. Between 2017 and 2019, the percentage of high school students who vape rose almost 2.5 times, from 11.7% to 27.5%, according to the Centers for Disease Control. In 2020, that percentage has dipped to about 20%, perhaps due in part to vaping being linked to more than 2,500 hospitalizations nationwide—and 55 deaths, including one in Utah—before the end of 2019.

Previous studies have suggested that social media, including Twitter, could be driving the popularity of e-cigarette usage as well as providing a forum for misinformation about the risks of using these devices. Intrigued, the researchers involved in the current study sought to find out what Twitter users, particularly teens, are posting about JUUL, the most popular e-cigarette brand, which accounts for 76% of the vaping market.

Using vaping-related keywords such as "JUUL," "vaping pod," and "pod mod," the researchers accessed a free Twitter application that allowed them to collect 29,590 relevant tweets posted nationwide from July 2018 to August 2019. After eliminating duplicates, they used both manual and computational machine learning techniques to analyze the remaining 11,556 unique English language tweets.

Of the 4,000 tweets that were manually analyzed, the researchers found that 3,152 (79%) specifically mentioned JUUL or JUUL-related products and accessories. Of these, 1,792 (57%) referred to first-person usage such as, "I left my JUUL at the party last night." Overall sentiment was more positive ("I love JUUL") than negative ("I will never touch JUUL again!"). Only 45 tweets (1%) mentioned JUUL as a means of smoking cessation; 216 (7%) referred to possible health benefits or concerns.

"I was expecting that few tweets would mention smoking cessation but wasn't expecting only 1%", says Mike Conway, Ph.D., senior author of the study and assistant professor of biomedical informatics at U of U Health. "I was also expecting there to be more discussion of health-related issues, which turned out to be largely absent from our dataset."

The researchers manually identified more than 200 tweets that likely were from underage users ("For my 16th birthday, I want mango JUUL pods"). They then used machine-learning algorithms to see if computers could identify these underage tweets faster and more accurately among 7,356 tweets that were not manually analyzed. They did.

"By developing machine-learning algorithms, we can identify underage tweets with 99% accuracy in just minutes or even seconds," Benson says

The study only analyzed a small number of the total available tweets stored on Twitter. The keyword list was not exhaustive and didn't include all e-cigarette devices used in the United States. The researchers also note that Twitter users may not be representative of the general U.S. population.

Moving forward, the researchers hope this information can be used to generate tailored health messages. The messages, based on keywords that appear in social media exchanges, could be automatically delivered to JUUL users who use Twitter and other sites, Conway says.

Explore further 1 in 4 JUULvapor tweeps is underage

More information: Ryzen Benson et al, Investigating the Attitudes of Adolescents and Young Adults Towards JUUL: Computational Study Using Twitter Data, JMIR Public Health and Surveillance (2020). DOI: 10.2196/19975

GM Ultium Drives to power new generation of e-vehicles

by Peter Grad , Tech Xplore

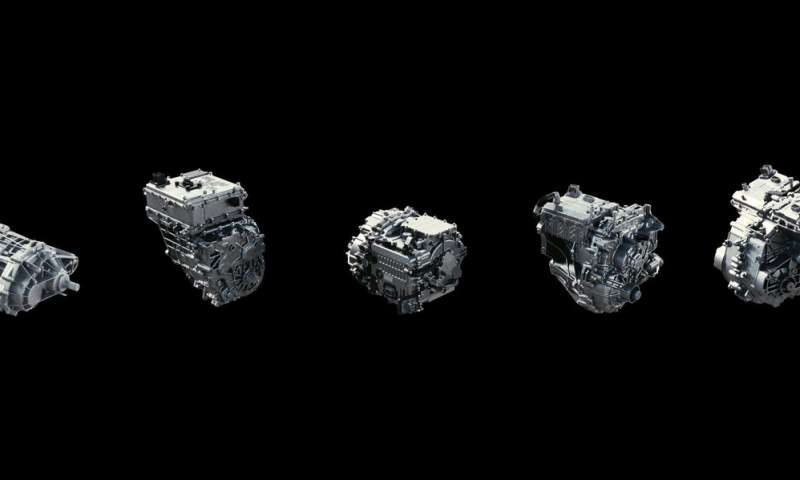

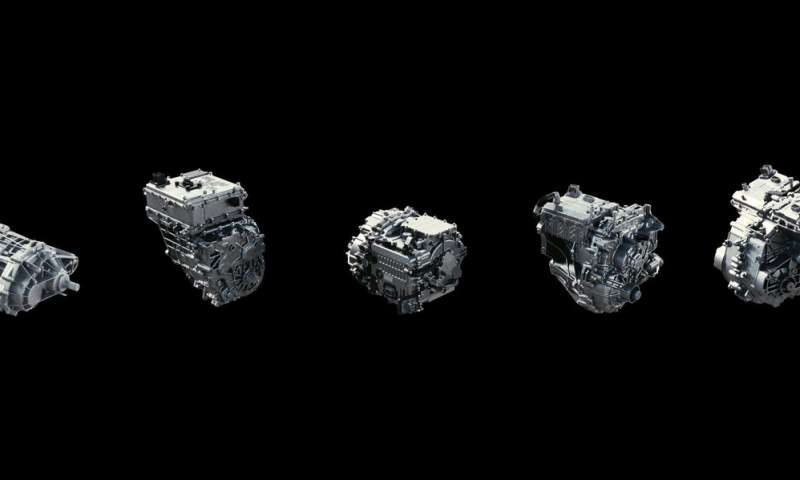

General Motors’ next-generation EVs are expected to be powered by a family of five interchangeable drive units and three motors, known collectively as “Ultium Drive.”. Credit: GM

General Motors on Wednesday announced plans for the production of a family of electric motors and drive units for its next generation of electric cars and trucks.

It will design and manufacture five interchangeable electric powertrains and three electric motors under the name Ultium Drive. The electric drive systems will be used across a spectrum of vehicles, from passenger cars to pickup trucks to high performance autos.

As it transitions to a complete electric lineup, GM vehicles will have better integration between the engine and electrical system and the car's other components and achieve greater efficiencies with Ultium Drive.

Adam Kwiatkowski, executive chief engineer for GM's global electrical propulsion, said "more of the battery energy now goes to the road" with Ultium Drive. "There is very very little, totally imperceptible motor lag, so as soon as you touch the accelerator pedal the vehicle responds in a very smooth fashion."

Kwiatkowski explained the new electric drive systems, also referred to as e-drives, combine gear, motor and power electronics into a single system that will more efficiently convert energy to drive the vehicle. By building the power electronics into the drive assemblies, greater power is attained in roughly half the space. And the system is lighter.

That means GM vehicles can achieve greater driving ranges, or carry fewer or smaller batteries and allow for even more passenger space. It also means cars that are priced lower.

GM "designed these drive units simultaneously with a full gambit of electric vehicles that fill out our portfolio," said Kwiatkowski. "They become synergistic and make them a really efficient package that's good for the performance of the vehicle, good for driving customer enthusiasm, and most importantly it's good for cost efficiency."

Earlier this year, GM unveiled its Ultium battery technology that will produce 200 kilowatt hours worth of energy and will ride up to 400 miles on a single charge.

The move comes at a critical time for GM as a formidable EV competitor, Tesla, sees its share prices soaring by more than 400 percent in recent months. Two factors driving Tesla's success are its powerful engine systems and energy efficiencies. Tesla's permanent magnet reluctance motors achieve a 97 percent level of efficiency.

GM will not totally abandon its relationships with other manufacturers. It is currently partnering with Nikola in the production of the Badger pickup truck. That deal may be shaky, however, as Nikola recently became engulfed in controversy over claims it made misleading statements about the capabilities of its first truck, Nikola One.

But GM officials said they want to push forward with the design and development of the new e-drive technology on their own, even though other established manufacturers could offer greater scale and lower costs for some parts.

The powertrain systems are expected to be seen in the new Lyriq luxury SUV, the Hummer EV due in October, the new generation Bolt EV (whose production has been delayed until 2021) and the crossover Bolt EUV slated for arrival next summer.

Explore further GM to make electric vehicle, supply batteries for Nikola

Wildfire on the rise since 1984 in Northern California's coastal ranges

by Kat Kerlin, UC Davis

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

High-severity wildfires in northern coastal California have been increasing by about 10 percent per decade since 1984, according to a study from the University of California, Davis, that associates climate trends with wildfire.

The study, published online in Environmental Research Letters, shows that the drought of 2012-2016 nearly quadrupled the area burned severely, compared to the relatively cooler drought of 1987-1992.

"The severity of wildfires has been increasing over the past four decades," said lead author Yuhan Huang, a graduate student researcher at UC Davis. "We found that fires were much bigger and more severe during dry and hot years compared to other climatic conditions."

Heat Wave Fans Flames

The study area includes coastal foothills and mountains surrounded by Central Valley lowlands to the east and stretching north to the Klamath Mountains. Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument resides in the southeast portion. It and several areas described in the study have been impacted by wildfire in recent months during a heat wave and the largest wildfire season recorded in California.

"Most of the fires occurring now are exacerbated by this heat wave," said co-leading author Yufang Jin, an associate professor in the UC Davis Department of Land, Air and Water Resources. "Our study shows how prolonged and historic dry conditions lead to extreme behaviors of wildfires, especially when they coincide with warmer temperature."

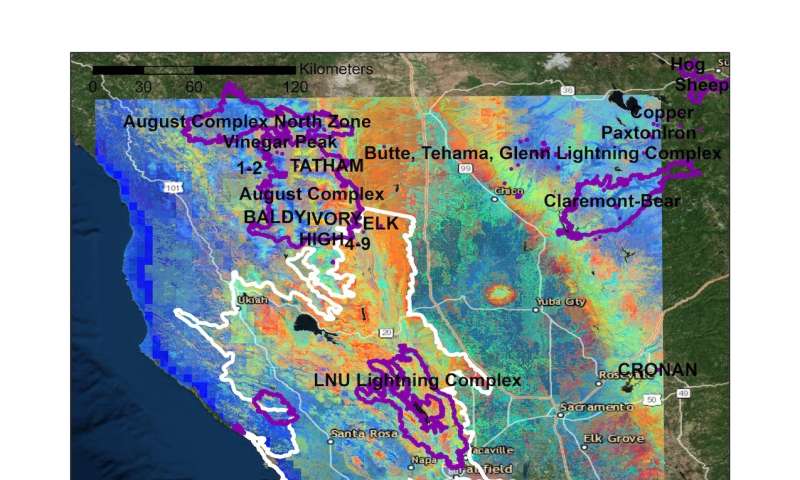

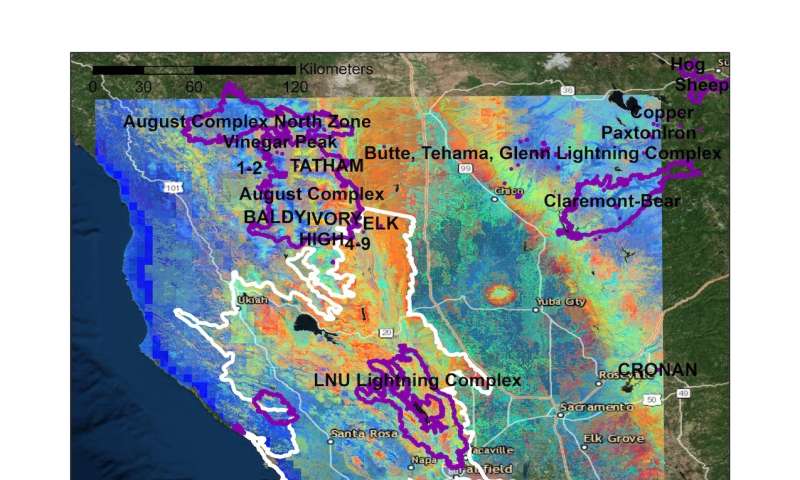

This map overlays the probability of burn severity in California's northern coastal mountains, as forecasted in a UC Davis study, with burn perimeters of wildfires burning in September 2020. Credit: UC Davis

The Hot And Dry Difference

The scientists used a machine-learning model that enables near real-time prediction of the likelihood of different levels of fire severity, given ignition. The model shows that during dry years, the northwest and southern parts of the study area are particularly at risk of high-severity fires, although the entire area is susceptible.

According to the historical data, about 36 percent of all fires between 1984 and 2017 in the mapped area burned at high severity, with dry years experiencing much higher burn severity. During wet years, however, only about 20 percent of burns were considered high-severity fires, while the remainder burned at moderate or low severity. Higher temperature further amplified the severity of wildfires.

The research highlights the importance of careful land-use planning and fuel management in the state's most vulnerable areas to reduce the risk of large, severe fires as the climate becomes drier and warmer.

"Those are things we can control in the short-term," Jin said. "Prioritizing high-risk areas is something more practical to reduce the damages."

Explore further

More information: Yuhan Huang et al, Intensified burn severity in California's northern coastal mountains by drier climatic condition, Environmental Research Letters (2020). DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/aba6af

Researchers discover effective pathway to convert carbon dioxide into ethylene

by University of California, Los Angeles

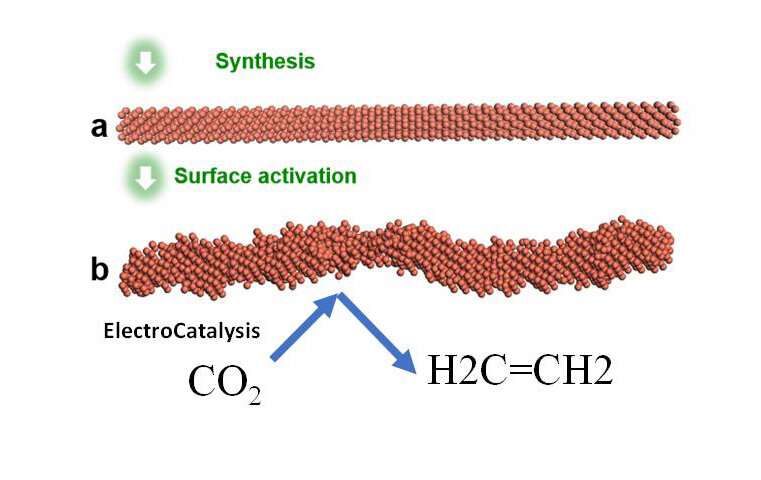

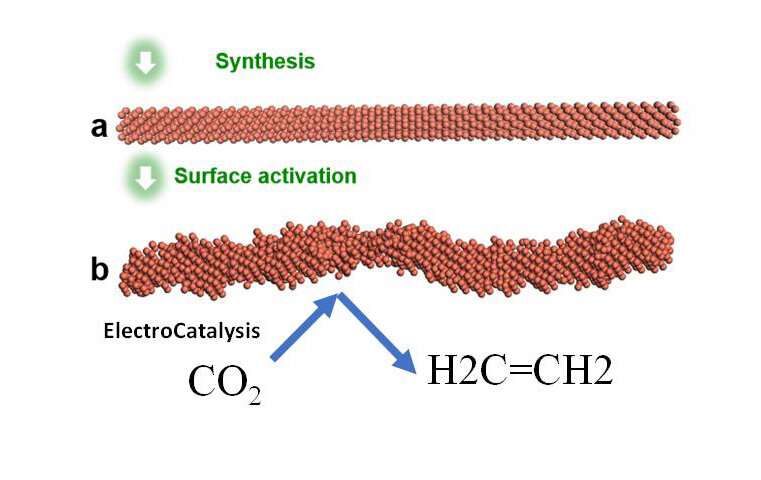

Illustration of the ElectroCatalysis system which synthesized the smooth nanowire and then activated it by applying a voltage to get the rough stepped surface that is highly selective for CO2 reduction to ethylene. Credit: Yu Huang and William A. Goddard III

A research team from Caltech and the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering has demonstrated a promising way to efficiently convert carbon dioxide into ethylene—an important chemical used to produce plastics, solvents, cosmetics and other important products globally.

The scientists developed nanoscale copper wires with specially shaped surfaces to catalyze a chemical reaction that reduces greenhouse gas emissions while generating ethylene—a valuable chemical simultaneously. Computational studies of the reaction show the shaped catalyst favors the production of ethylene over hydrogen or methane. A study detailing the advance was published in Nature Catalysis.

"We are at the brink of fossil fuel exhaustion, coupled with global climate change challenges," said Yu Huang, the study's co-corresponding author, and professor of materials science and engineering at UCLA. "Developing materials that can efficiently turn greenhouse gases into value-added fuels and chemical feedstocks is a critical step to mitigate global warming while turning away from extracting increasingly limited fossil fuels. This integrated experiment and theoretical analysis presents a sustainable path towards carbon dioxide upcycling and utilization."

Currently, ethylene has a global annual production of 158 million tons. Much of that is turned into polyethylene, which is used in plastic packaging. Ethylene is processed from hydrocarbons, such as natural gas.

"The idea of using copper to catalyze this reaction has been around for a long time, but the key is to accelerate the rate so it is fast enough for industrial production," said William A. Goddard III, the study's co-corresponding author and Caltech's Charles and Mary Ferkel Professor of Chemistry, Materials Science, and Applied Physics. "This study shows a solid path towards that mark, with the potential to transform ethylene production into a greener industry using CO2 that would otherwise end up in the atmosphere."

Using copper to kick start the carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction into ethylene reaction (C2H4) has suffered two strikes against it. First, the initial chemical reaction also produced hydrogen and methane—both undesirable in industrial production. Second, previous attempts that resulted in ethylene production did not last long, with conversion efficiency tailing off as the system continued to run.

To overcome these two hurdles, the researchers focused on the design of the copper nanowires with highly active "steps"—similar to a set of stairs arranged at atomic scale. One intriguing finding of this collaborative study is that this step pattern across the nanowires' surfaces remained stable under the reaction conditions, contrary to general belief that these high energy features would smooth out. This is the key to both the system's durability and selectivity in producing ethylene, instead of other end products.

The team demonstrated a carbon dioxide-to-ethylene conversion rate of greater than 70%, much more efficient than previous designs, which yielded at least 10% less under the same conditions. The new system ran for 200 hours, with little change in conversion efficiency, a major advance for copper-based catalysts. In addition, the comprehensive understanding of the structure-function relation illustrated a new perspective to design highly active and durable CO2 reduction catalyst in action.

Huang and Goddard have been frequent collaborators for many years, with Goddard's research group focusing on the theoretical reasons that underpin chemical reactions, while Huang's group has created new materials and conducted experiments. The lead author on the paper is Chungseok Choi, a graduate student in materials science and engineering at UCLA Samueli and a member of Huang's laboratory.

Explore further Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to ethanol

More information: Chungseok Choi et al, Highly active and stable stepped Cu surface for enhanced electrochemical CO2 reduction to C2H4, Nature Catalysis (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41929-020-00504-x

A scientific first: How psychedelics bind to key brain cell receptor

by University of North Carolina Health Care

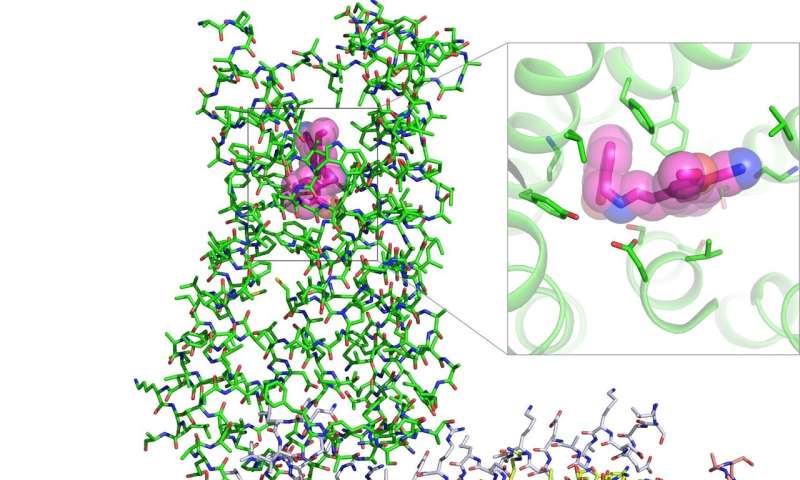

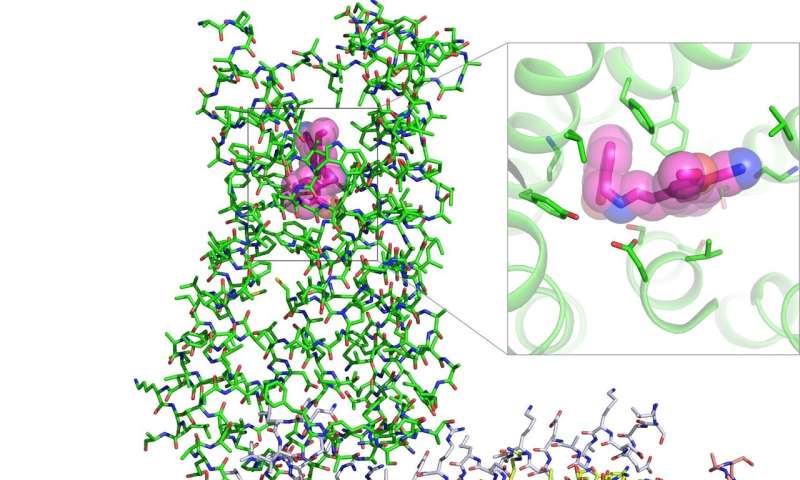

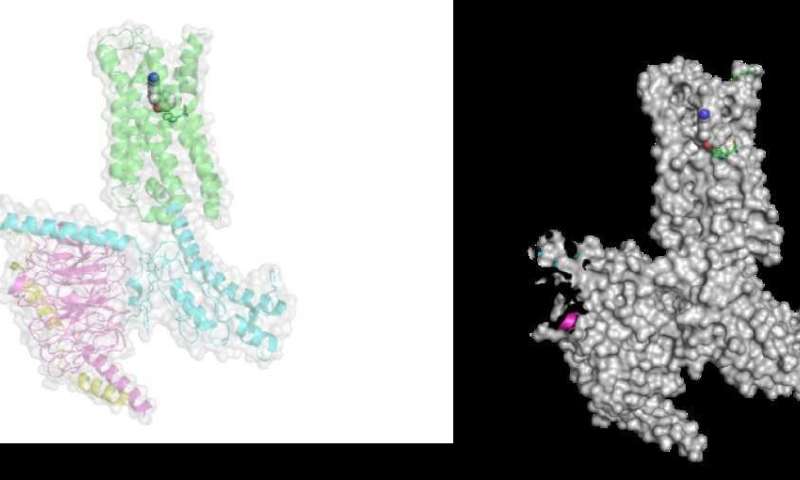

This illustration shows the chemical architecture of amino acids that make up the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor complex bound to a psychedelic compound (pink, top) Credit: Roth Lab (UNC School of Medicine)

Psychedelic drugs such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline cause severe and often long-lasting hallucinations, but they show great potential in treating serious psychiatric conditions, such as major depressive disorder. To fully investigate this potential, scientists need to know how these drugs interact with brain cells at the molecular level to cause their dramatic biological effects. Scientists at UNC-Chapel Hill and Stanford have just taken a big step in that direction.

For the first time, scientists in the UNC lab of Bryan L. Roth, MD, Ph.D., and the Stanford lab of Georgios Skiniotis, Ph.D., solved the high-resolution structure of these compounds when they are actively bound to the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor (HTR2A) on the surface of brain cells.

This discovery, published in Cell, is already leading to the exploration of more precise compounds that could eliminate hallucinations but still have strong therapeutic effects. Also, scientists could effectively alter the chemical composition of drugs such as LSD and psilocybin—the psychedelic compound in mushrooms that has been granted breakthrough status by the FDA to treat depression.

"Millions of people have taken these drugs recreationally, and now they are emerging as therapeutic agents," said co-senior author Bryan L. Roth, MD, Ph.D., the Michael Hooker Distinguished Professor of Pharmacology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. "Gaining this first glimpse of how they act at the molecular level is really important, a key to understanding how they work. Given the remarkable efficacy of psilocybin for depression (in Phase II trials), we are confident our findings will accelerate the discovery of fast-acting antidepressants and potentially new drugs to treat other conditions, such as severe anxiety and substance use disorder."

Scientists believe that activation of HTR2A, which is expressed at very high levels in the human cerebral cortex, is key to the effects of hallucinogenic drugs. "When activated, the receptors cause neurons to fire in an asynchronous and disorganized fashion, putting noise into the brain's system," said Roth, who holds a joint faculty appointment at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. "We think this is the reason these drugs cause a psychedelic experience. But it isn't at all clear how these drugs exert their therapeutic actions."

In the current study, Roth's lab collaborated with Skiniotis, a structural biologist at the Stanford University School of Medicine. "A combination of several different advances allowed us to do this research," Skiniotis said. "One of these is better, more homogeneous preparations of the receptor proteins. Another is the evolution of cryo-electron microscopy technology, which allows us to view very large complexes without having to crystalize them."

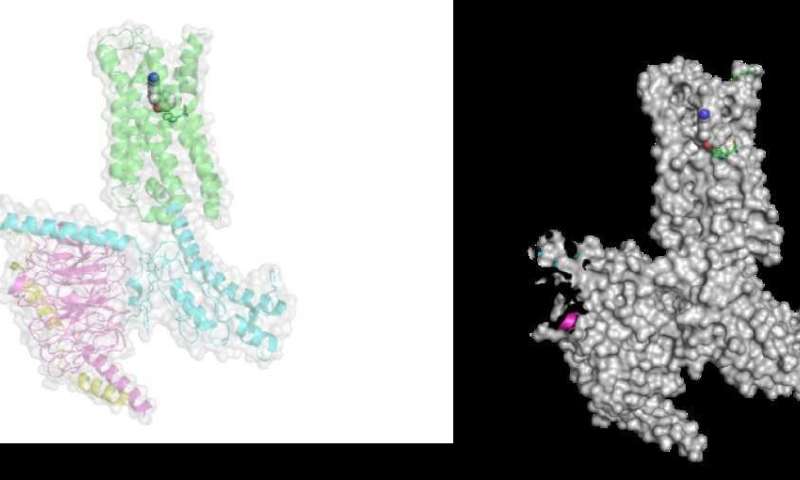

On left, a cryo-electron microscopy image of the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor complex; on right, an illustration of the receptor complex bound to a psychedelic compound. Credit: Skiniotis Lab, Stanford / Roth Lab, UNC-Chapel Hill

Roth credits co-first author Kuglae Kim, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in his lab, for steadfastly exploring various experimental methods to purify and stabilize the very delicate serotonin receptors.

"Kuglae was amazing," Roth said. "I'm not exaggerating when I say what he accomplished is among the most difficult things to do. Over three years in a deliberate, iterative, creative process, he was able to modify the serotonin protein slightly so that we could get sufficient quantities of a stable protein to study."

The research team used Kim's work to reveal the first X-ray crystallography structure of LSD bound to HTR2A. Importantly, Stanford investigators then used cryo-EM to uncover images of a prototypical hallucinogen, called 25-CN-NBOH, bound together with the entire receptor complex, including the effector protein Gαq. In the brain, this complex controls the release of neurotransmitters and influences many biological and neurological processes.

The cryo-EM image is like a map of the complex, which Kim used to illustrate the exact structure of HTR2A at the level of amino acids—the basic building blocks of proteins such as serotonin receptors.

Roth, a psychiatrist and biochemist, leads the Psychoactive Drug Screening Program, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. This gives his lab access to hallucinogenic drugs for research purposes. Normally, these compounds are difficult to study in the lab because they are regulated by the Drug Enforcement Agency as Schedule 1 drugs.

Roth and colleagues are now applying their findings to structure-based drug discovery for new therapeutics. One of the goals is to discover potential candidates that may be able offer therapeutic benefit without the psychedelic effects.

"The more we understand about how these drugs bind to the receptors, the better we'll understand their signaling properties," Skiniotis says. "This work doesn't give us the whole picture yet, but it's a fairly large piece of the puzzle."

Explore further Scientists reveal host- SARS-CoV-2 protein targets for drug repurposing