by Massachusetts General Hospital

One of the of the most important questions in managing a hospital's response to the COVID-19 pandemic is determining when healthcare workers infected with COVID-19 can return to the job. Recently, investigators from Mass General Brigham (MGB) assessed the experience of using a test-based protocol in over 1,000 infected health care workers.

Their research was published in the latest edition of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology.

The "test-based" approach involves repeat testing after resolution of symptoms until two consecutive negative tests are obtained 24 hours apart. In the alternative time-plus-symptoms approach, healthcare workers return to work after a set period of time since their symptom onset (or in the case of asymptomatic infection, the date of their positive test) has elapsed and symptoms, if present, have improved or resolved.

"We've learned a lot throughout the pandemic," explains Erica S. Shenoy, MD, Ph.D., associate chief of the Infection Control Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the study's lead author. "For example, we now know from multiple published studies that individuals can have repeat positive tests for weeks and those positive test do not reflect infectivity after their initial illness has resolved." These findings have led to modifications in how public health and healthcare facilities determine how long individuals need to be isolated to prevent transmission to others, Shenoy says.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)'s April guidance advised either repeat "test-based" strategy to determine when workers could return to their healthcare jobs or "time-plus-symptoms" approach. Under the test-based strategy, healthcare workers had to have two negative back-to-back PCR tests to return to work.

For this study, conducted between March 7 and April 22, 2020, employees from across Mass General Brigham (MGB) health system who showed symptoms of COVID-19 were referred to its Occupational Health Services department for evaluation and a nasopharyngeal (NP) sample test using viral RNA nucleic acid amplification methods.

Return to work criteria at that time required: resolution of fever without fever-reducing medications, improvement in respiratory symptoms, and at least two consecutive negative nasopharyngeal tests collected longer than or equal to 24 hours apart. There was no minimum interval of time from resolution of symptoms to first test of clearance specified.

The researchers then analyzed the data to evaluate results of the two strategies and found that using resolution of symptoms and passage of time would have averted more than 4,000 days of lost worktime, or a mean of 7.2 additional days of work lost per employee compared to using a time-plus-symptom approach. Both approaches are options per public health recommendations, though more recently, the time-plus-symptom approach is now the preferred strategy per the CDC the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, and has replaced the prior test-based approach at MGB. One additional potential benefit of moving away from test-based approaches, though not assessed in this study, was the psychological impact on employees of repeat testing. "We've had employees who tested positive repeatedly but had recovered for weeks and they were frustrated we couldn't bring them back to work," Shenoy says. About 70 percent of participants had at least one negative test result during the study, and of those, about 62 percent had a two negative test results in a row, she adds.

A substantial number of healthcare workers diagnosed and treated for COVID-19 had repeatedly positive PCR tests. Such long duration of PCR positivity has been seen in other studies as well.

Determining when workers can return to work is a process that can affect many aspects of hospital operations, Shenoy says. "Patient and worker safety, flow of resources, speed and access to care, are some of the things impacted."

Based on the studies findings, and evolving public health guidance to prefer time-plus-symptom over test-based strategies, MGB moved to the latter over the summer. "Moving to a time+symptom approach was a vast improvement over past reliance on a less predictable test-based approach. Employees are now able to anticipate when they will be allowed to return to work, and it has reduced the strain on our testing capacity. This revision in testing strategy is consistent with our evolving medical understanding of test results and in keeping with our high commitment to workplace safety," said Dean Hashimoto, MD, chief medical officer of MGB Occupational Health Services.

Explore further Follow the latest news on the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak

More information: Erica S. Shenoy et al, Healthcare worker infection with SARS-CoV-2 and test-based return to work, Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology (2020).

Provided by Massachusetts General Hospital

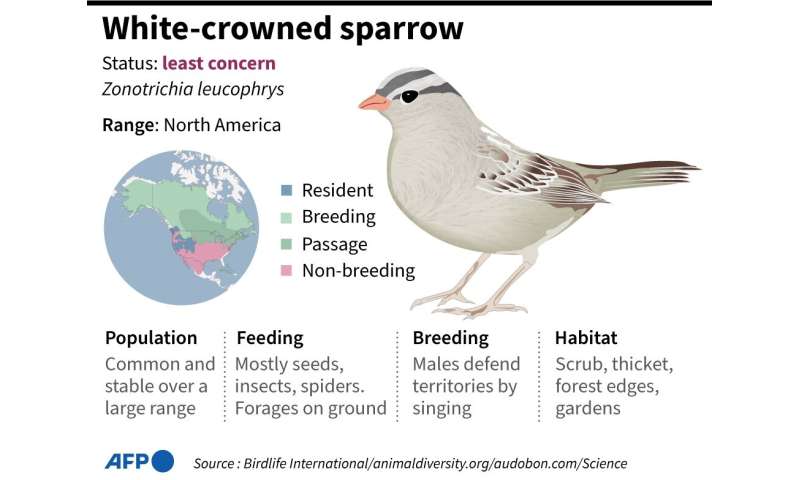

Species factfile on the white-capped sparrows.

Species factfile on the white-capped sparrows.