Taiwan in Time: Resting in stone

Prehistoric slate coffins found in countless archaeological sites across Taiwan were often tailor-made to fit the size of the deceased, including miniature ones for miscarried fetuses

Sept. 28 to Oct . 4

A large number of 3000-year-old slate coffins were unearthed on a hill near Nanhe Village (南和村) in Pingtung County on Sept. 30, 1985. Unfortunately, the United Daily News (聯合報) noted that they had been seriously damaged by construction, and no artifacts or human remains were found.

Although the newspaper called the find a “significant discovery,” little information can be gleaned about this specific site because it’s just one of countless locations where stone sarcophagi have been unearthed across southern and eastern Taiwan, and as north as Yilan County.

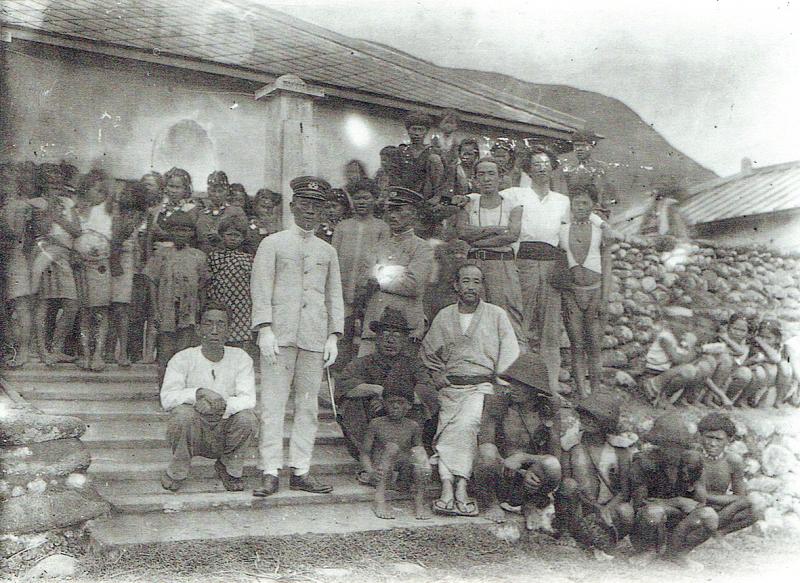

Nenozo Utsurikawa, front row in kimono, former head of Taihoku Imperial University’s Institute of Ethnology, was the first anthropologist to discover slate coffins in Taiwan in 1930.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

These stone receptacles for the dead were first found in 1930 at a site in Kenting (墾丁) by a Japanese team led by anthropologist Utsurikawa Nenozo, who unearthed 31 coffins after four excavations. They contained abundant artifacts such as jade and pottery shards, and this venture is considered Taiwan’s first academic archeological excavation. According to contemporary research by Kenting National Park Headquarters, human activity in the area can be traced back to over 6,500 years, encompassing over 70 archaeological sites.

The best-known mass stone coffin site is the Beinan site (卑南遺址) in Taitung County, which was revealed in 1980 during a railroad rerouting project. It is Taiwan’s largest known prehistoric settlement with a sophisticated culture that included indoor burials, teeth extraction and a social hierarchy, and boasting about 2,000 coffins with many more either destroyed or still buried. It’s the largest prehistoric stone graveyard ever found around the Pacific Rim.

Throughout the years, coffins continued to be found at various construction projects, the latest coming in 2011 when three, 4,000-year-old sarcophagi were found in Taitung.

Replica stone coffins are on display at Beinan Cultural Park in Taitung County.

Photo: CNA

FIRST FINDS

After receiving his PhD in anthropology from Harvard University, Utsurikawa became the head of the newly established Institute of Ethnology at Taihoku Imperial University (today’s National Taiwan University), where he conducted extensive field research on the island’s various Aboriginal groups.

According to the National Taiwan Museum of History, Utsurikawa’s dig at the Kenting site was by no means up to modern standards and techniques, but it still paved the way for future endeavors. In 1935, the colonial government deemed the site a National Historic Site and put it under protection. But war soon broke out between Japan and China and the findings at the site remained unpublished until the 1990s.

A member of an archeological team dusts off the top of a slate coffin during a dig.

Photo: Tung Chen-kuo, Taipei Times

Later research determined that the site was up to 4,000 years old, and may have belonged to the neolithic Niuchoutzu (牛稠子) culture, of which there are about 15 sites alone within the national park. Rice grain imprints were found in some of the pottery at one of the sites, which is the earliest evidence of cultivation in the Hengchun peninsula. From the human remains, they determined that the inhabitants practiced teeth extraction and chewed betel nuts.

Due to the rapid development of the area, the Kenting site has been seriously damaged over the years, and by 2004, anthropologist Lien Chao-mei (連照美) lamented its condition. Lien collected and edited the Japanese findings into a book that was published in 2007.

EQUALITY IN DEATH

This stone coffin contained multiple corpses.

Photo: Huang Ming-tang, Taipei Times

Long before the stone coffins were unearthed at the Beinan site, the location was already known to Japanese scholars, who had examined two large stone pillars in 1896. Later archaeologists found that there were numerous such pillars in the area. Japanese-era research mostly focused on these monoliths, and only in 1945 did two archaeologists conduct a brief dig despite American airstrikes across the island. They found pottery and the remains of old slate dwellings.

No further excavations were conducted until the site was damaged by the railway project in 1980, which drew public attention, which forced the government to preserve the artifacts. Lien and Sung Wen-hsun (宋文薰) were in charge of the efforts, which took 13 phases over nine years to complete. It was determined that the Beinan culture began about 5,300 years ago and reached its peak between 3,500 and 2,300 years ago.

The stone coffins found at this site were all positioned along a north-south axis, which was also how the inhabitants arranged their dwellings. The dead were placed lying down with their toes pointed northward toward Dulan Mountain (都蘭山), which is believed to be their sacred mountain and the resting place of their souls.

Several miniature slate coffins, the smallest one measuring 40cm long, were found in Taitung in 2007.

Photo: CNA

Although most coffins only held one corpse, there were larger ones that held at least five. These were usually the resting places for powerful families as they contained precious burial objects. One 183-cm long coffin contained a whopping 4,449 artifacts, from jade to weapons and all manner of tool.

Archaeologists also found tiny 18-cm ones that probably held miscarried fetuses. Infants and children were usually buried in their own small sarcophagi, and those under 130cm long made up roughly one-third of the 2,000 odd coffins found on site — indicating a high child mortality rate. The fact that coffins were made for even miscarriages, shows how equally the Beinan people treated all deaths, states a National Museum of Prehistory report, although the underage corpses were seldom buried with any artifacts. Child coffins have also been found at other sites across Taiwan.

Many sarcophagi were buried inside the house, “to accompany those who were still alive,” the report states, showing a close attachment between the dead and the living.

There is still no concrete evidence that these “rock coffins” were used for corpses.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Aside from slate coffins, experts have also discovered “rock coffins,” which are directly carved onto the surface of a large volcanic tuff. These were found mostly on the east coast, and, with only 16 discovered so far, are quite rare.

Although the sizes of the rectangular depressions are almost all large enough to fit a fully-grown human, there’s still no concrete evidence that they were actually used to contain corpses.

Amis Aborigines once chipped pieces off of these ancient “coffins” during droughts to pray for rain, but their original purpose remains a mystery.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.