New global temperature data will inform study of climate impacts on health, agriculture

by University of Minnesota

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

A seemingly small one-to-two degree change in the global climate can dramatically alter weather-related hazards. Given that such a small change can result in such big impacts, it is important to have the most accurate information possible when studying the impact of climate change. This can be especially challenging in data sparse areas like Africa, where some of the most dangerous hazards are expected to emerge.

A new data set published in the journal Scientific Data provides high-resolution, daily temperatures from around the globe that could prove valuable in studying human health impacts from heat waves, risks to agriculture, droughts, potential crop failures, and food insecurity.

Data scientists Andrew Verdin and Kathryn Grace of the Minnesota Population Center at the University of Minnesota worked with colleagues at the Climate Hazards Center at the University of California Santa Barbara to produce and validate the data set.

"It's important to have this high-resolution because of the wide-ranging impacts—to health, agriculture, infrastructure. People experiencing heat waves, crop failures, droughts—that's all local," said Verdin, the lead author.

By combining weather station data, remotely sensed infrared data and the weather simulation models, this new data set provides daily estimates of 2-meter maximum and minimum air temperatures for 1983-2016. Named CHIRTS-daily, this data provides high levels of accuracy, even in areas where on-site weather data collection is sparse. Current efforts are focused on updating the data set in near real time.

"We know that the next 20 years are going to bring more extreme heat waves that will put millions or even billions of people in harm's way. CHIRTS-daily will help us monitor, understand, and mitigate these rapidly emerging climate hazards," said Chris Funk, director of the Climate Hazards Center.

Additionally, the people who are most vulnerable are often located in areas where publicly available weather station data are deteriorating or unreliable. Areas with rapidly expanding populations and exposures (e.g. Africa, Central America, and parts of Asia) can't rely on weather observations. By combining different sources of weather information, each contributes to provide detail and context for a more accurate, global temperature dataset.

"We're really excited about the possibilities for fine-scale, community-focused climate-health data analyses that this dataset can support. We're excited to see researchers use it," said co-author Kathryn Grace.

Understanding how birds respond to extreme weather can inform conservation efforts

More information: Andrew Verdin et al. Development and validation of the CHIRTS-daily quasi-global high-resolution daily temperature data set, Scientific Data (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41597-020-00643-7

Provided by University of Minnesota

The deep sea is slowly warming

by American Geophysical Union

A new study finds temperatures in the deep sea fluctuate more than scientists previously thought. Credit: Doug White.

New research reveals temperatures in the deep sea fluctuate more than scientists previously thought and a warming trend is now detectable at the bottom of the ocean.

In a new study in AGU's journal Geophysical Research Letters, researchers analyzed a decade of hourly temperature recordings from moorings anchored at four depths in the Atlantic Ocean's Argentine Basin off the coast of Uruguay. The depths represent a range around the average ocean depth of 3,682 meters (12,080 feet), with the shallowest at 1,360 meters (4,460 feet) and the deepest at 4,757 meters (15,600 feet).

They found all sites exhibited a warming trend of 0.02 to 0.04 degrees Celsius per decade between 2009 and 2019—a significant warming trend in the deep sea where temperature fluctuations are typically measured in thousandths of a degree. According to the study authors, this increase is consistent with warming trends in the shallow ocean associated with anthropogenic climate change, but more research is needed to understand what is driving rising temperatures in the deep ocean.

"In years past, everybody used to assume the deep ocean was quiescent. There was no motion. There were no changes," said Chris Meinen, an oceanographer at the NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory and lead author of the new study. "But each time we go look we find that the ocean is more complex than we thought."

The challenge of measuring the deep

Researchers today are monitoring the top 2,000 meters (6,560 feet) of the ocean more closely than ever before, in large part due to an international program called the Global Ocean Observing System. Devices called Argo floats that sink and rise in the upper ocean, bobbing along in ocean currents, provide a rich trove of continuous data on temperature and salinity.

The deep sea, however, is notoriously difficult to access and expensive to study. Scientists typically take its temperature using ships that lower an instrument to the seafloor just once every ten years. This means scientists' understanding of the day-to-day changes in the bottom half of the ocean lag far behind their knowledge of the surface.

Meinen is part of a team at NOAA carrying out a rare long-term study at the bottom of the ocean, but until recently, the team thought the four devices they had moored at the bottom of the Argentine Basin were just collecting information on ocean currents. Then Meinen saw a study by the University of Rhode Island showcasing a feature of the device he had been completely unaware of. A temperature sensor was built into the instrument's pressure sensor used to study currents and had been incidentally collecting temperature data for the entirety of their study. All they had to do was analyze the data they already had.

"So we went back and we calibrated all of our hourly data from these instruments and put together what is essentially a continuous 10-year-long hourly record of temperature one meter off the seafloor," Meinen said.

Dynamic depths

The researchers found at the two shallower depths of 1,360 and 3,535 meters (4,460 feet and 11,600 feet), temperatures fluctuated roughly monthly by up to a degree Celsius. At depths below 4,500 meters (14,760 feet), temperature fluctuations were more minute, but changes followed an annual pattern, indicating seasons still have a measurable impact far below the ocean surface. The average temperature at all four locations went up over the course of the decade, but the increase of about 0.02 degrees Celsius per decade was only statistically significant at depths of over 4,500 meters.

According to the authors, these results demonstrate that scientists need to take the temperature of the deep ocean at least once a year to account for these fluctuations and pick up on meaningful long-term trends. In the meantime, others around the world who have used the same moorings to study deep sea ocean currents could analyze their own data and compare the temperature trends of other ocean basins.

"There are a number of studies around the globe where this kind of data has been collected, but it's never been looked at," Meinen said. "I'm hoping that this is going to lead to a reanalysis of a number of these historical datasets to try and see what we can say about deep ocean temperature variability."

A better understanding of temperature in the deep sea could have implications that reach beyond the ocean. Because the world's oceans absorb so much of the world's heat, learning about the ocean's temperature trends can help researchers better understand temperature fluctuations in the atmosphere as well.

"We're trying to build a better Global Ocean Observing System so that in the future, we're able to do better weather predictions," Meinen said. "At the moment we can't give really accurate seasonal forecasts, but hopefully as we get better predictive capabilities, we'll be able to say to farmers in the Midwest that it's going to be a wet spring and you may want to plant your crops accordingly."

Explore further

Recent Atlantic ocean warming unprecedentedClimate scientists Nicholas Balascio and Francois Lapointe working with an ice auger to drill in the 3.5m thick ice at South Sawtooth Lake, Ellesmere Island, Nunavut Territory, Canada. An ice auger extension is needed because the ice is so thick. Coring lake sediments can only be done after this tedious work, Lapointe notes. Credit: Mark B. Abbott

Taking advantage of unique properties of sediments from the bottom of Sawtooth Lake in the Canadian High Arctic, climate scientists have extended the record of Atlantic sea-surface temperature from about 100 to 2,900 years, and it shows that the warmest interval over this period has been the past 10 years.

A team led by Francois Lapointe and Raymond Bradley in the Climate System Research Center of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Pierre Francus at University of Québec-INRS analyzed "perfectly preserved" annual layers of sediment that accumulated in the lake on northern Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, which contain titanium left over from centuries of rock weathering. By measuring the titanium concentration in the different layers, scientists can estimate the relative temperature and atmospheric pressure over time.

The newly extended record shows that the coldest temperatures were found between about 1400-1600 A.D., and the warmest interval occurred during just the past decade, the authors report. Francus adds, "Our unique data set constitutes the first reconstruction of Atlantic sea surface temperatures spanning the last 3,000 years and this will allow climatologists to better understand the mechanisms behind long-term changes in the behavior of the Atlantic Ocean."

When temperatures are cool over the North Atlantic, a relatively low atmospheric pressure pattern is found over much of the Canadian High Arctic and Greenland. This is associated with slower snow melt in that region and higher titanium levels in the sediments. The opposite is true when the ocean is warmer—atmospheric pressure is higher, snow melt is rapid and the concentration of titanium decreases.

Lapointe says, "Using these strong links, it was possible to reconstruct how Atlantic sea surface temperatures have varied over the past 2,900 years, making it the longest record that is currently available." Details appear this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers report that their newly reconstructed record is significantly correlated with several other independent sediment records from the Atlantic Ocean ranging from north of Iceland to offshore Venezuela, confirming its reliability as a proxy for the long-term variability of ocean temperatures across a broad swath of the Atlantic. The record is also similar to European temperatures over the past 2,000 years, they point out.

Fluctuations in sea surface temperatures, known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), are also linked to other major climatic upheavals such as droughts in North America and the severity of hurricanes. However, because measurements of sea surface temperatures only go back a century or so, the exact length and variability of the AMO cycle has been poorly understood.

Climate warming in the Arctic is now twice or three times faster than the rest of the planet because of greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels, warming can be amplified or dampened by natural climate variability, such as changes in the surface temperature of the North Atlantic, which appear to vary over cycles of about 60-80 years.

Lapointe, who has carried out extensive fieldwork in the Canadian Arctic over the past decade, notes that "It has been common in recent summers for atmospheric high-pressure systems—clear-sky conditions—to prevail over the region. Maximum temperatures often reached 20 degrees Celsius, 68 degrees Fahrenheit, for many successive days or even weeks, as in 2019. This has had irreversible impacts on snow cover, glaciers and ice caps, and permafrost."

Bradley adds that, "The surface waters of the Atlantic have been consistently warm since about 1995. We don't know if conditions will shift towards a cooler phase any time soon, which would give some relief for the accelerated Arctic warming. But if the Atlantic warming continues, atmospheric conditions favoring more severe melting of Canadian Arctic ice caps and the Greenland ice sheet can be expected in the coming decades."

In 2019, Greenland Ice Sheet lost more than 500 billion tons of mass, a record, and this was associated with unprecedented, persistent high pressure atmospheric conditions."

Lapointe notes, "Conditions like this are currently not properly captured by global climate models, underestimating the potential impacts of future warming in Arctic regions."

Explore further

Scientists investigate effects of marine heat wave on ocean life off southern New England

by University of Rhode Island

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

A team of scientists from the University of Rhode Island and partner institutions depart today aboard the research vessel Endeavor for a five-day cruise to investigate the implications of a marine heat wave in the offshore waters of New England.

The waters on the continental shelf—extending from the coast to about 100 miles offshore—have been 2 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than usual since July, according to URI oceanographer Tatiana Rynearson, one of the leaders of the expedition. And that warmth could have significant impacts for local fisheries and the marine ecosystem.

"The water is very warm compared to the average of the last 40 years," said Rynearson, a professor at the URI Graduate School of Oceanography who studies plankton. "The question we're asking is, how is it affecting the ecosystem and the productivity of the continental shelf waters."

The Northeast Pacific Ocean experienced a similar marine heat wave in 2014 and 2015, when what was described as a "blob" of warm water spread offshore from Alaska to California, resulting in major die-offs of fish and seabirds and closures of fisheries.

"The impacts went all the way up the food chain from that warm blob of water," Rynearson said. "Similar dramatic impacts haven't been documented for New England waters, but we're going to try to understand what's going on out there."

Rynearson hopes the expedition will provide a clearer understanding of how the marine ecosystem responds to short-term heat waves and how it may react to the long-term temperature increases that are expected in the ocean due to the changing climate.

"We think these heat waves will happen more frequently in the future, so it's important to understand how the ecosystem responds to them," she said. "We're also interested in whether the response to this heat wave will give us insight into the general warming trend."

The expedition—which includes scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Wellesley College, University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—is part of a long-term ecological research project funded by the National Science Foundation. Its aim is to compare how variability in the environment affects the ecosystem, from microscopic plankton to fish.

"From our ongoing study we've learned that there are two different kinds of water out there—cold, nutrient-rich water that supports a lot of fisheries production, and warm, less-productive water," Rynearson said. "We're interested in the balance between how long the waters are warm and nutrient-poor versus cold and nutrient-rich."

The researchers will collect data along a transect from Narragansett to Martha's Vineyard and then southward about 100 miles to an area at the edge of the continental shelf where the water is about 5,000 feet deep. Along the way they will take water samples at various depths to evaluate how much plankton is in the water, the rate of photosynthesis, and the rate that tiny marine animals called zooplankton are feeding upon tiny marine plants called phytoplankton.

"We'll also be looking at what species of phytoplankton and zooplankton are out there, because there seem to be differences in the community when you have cold, nutrient-rich waters versus warm, nutrient-poor waters," said Rynearson. "We'll ask, are we still seeing a summer community of marine life out there or is it too late in the year for that."

The research team also aims to gain a better understanding of the marine food web by studying the links between the tiniest creatures and the forage fish that are fed upon by the top predators in the ocean and captured in local fisheries.

"We're probing a part of the food web that's not well understood in terms of the transfer of energy or the response to climate change," Rynearson said. "That part of the food web is a bit of a black hole, and we want to shine some light in there."

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all of the participants in the expedition quarantined for two weeks prior to boarding the ship, and fewer scientists than usual will be aboard. Among the participants will be URI graduate students Victoria Fulfer and Erin Jones and postdoctoral researcher Pierre Marrec.

"A research cruise is always exciting and welcome, but during the pandemic, the cruise participants are particularly thrilled to be out at sea," Rynearson said.

Studies investigate marine heatwaves, shifting ocean currents

Data shows that advice to women to 'lean in,' be more confident doesn't help

by Leonora Risse, The Conversation

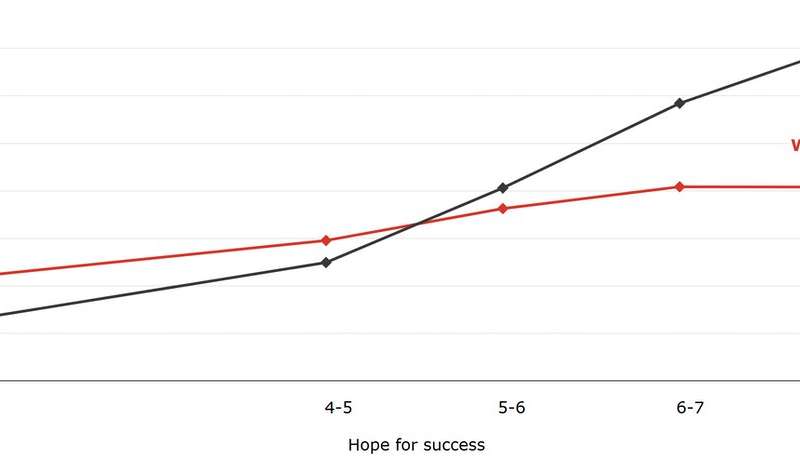

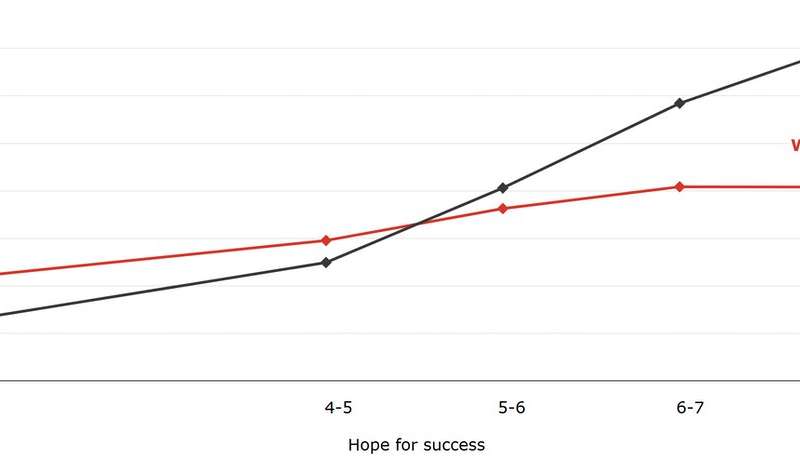

Promotion probabilities are estimated for 2013 using hope for success responses.collected in 2012. Categories at the lower levels are grouped due to small sample sizes. Credit: Source: Author’s analysis using the HILDA Survey

"Just be more confident, be more ambitious, be more like a man."

These are the words of advice given over and over to women in a bid to close the career and earnings gaps between women and men.

From self-help books to confidence coaching, the message to "lean in" and show confidence in the workplace is pervasive, propelled by Facebook Executive Sheryl Sandberg through her worldwide Lean In movement:

"Women are hindered by barriers that exist within ourselves. We hold ourselves back in ways both big and small, by lacking self-confidence, by not raising our hands, and by pulling back when we should be leaning in."

The efforts are well intended, because women are persistently underrepresented in senior and leadership positions.

But where is the proof they work?

Repeated advice needn't be right

As a labor economist, and a recipient of such advice throughout my own career, I wanted to find out.

So I used Australian survey data to investigate the link between confidence and job promotion for both men and women. The results have just been published in the Australian Journal of Labour Economics.

The nationally-representative Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey includes a measure of a person's confidence to take on a challenge.

The measure is called achievement motivation.

It is made up of hope for success which we measure by asking people how much they agree with statements such as

when confronted by a difficult problem, I prefer to start on it straight away

I like situations where I can find out how capable I am

I am attracted to tasks that allow me to test my abilities

And it is made up of fear of failure which is measured by a person's agreement with statements such as

I start feeling anxious if I do not understand a problem immediately

In difficult situations where a lot depends on me, I am afraid of failing

I feel uneasy about undertaking a task if I am unsure of succeeding

More than 7,500 workers provided answers to these questions in the 2013 HILDA survey.

Confidence matters, with a catch

Using a statistical technique called Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition I investigated the link between their answers and whether or not they experienced a promotion in the following year.

After controlling for a range of factors, including the job opportunities on offer, I discovered higher hope for success was clearly linked to a higher likelihood of promotion.

But there was a catch: the link was only clear for men.

For women, there was no clear evidence stronger confidence enhanced job promotion prospects.

Put differently, "leaning in" provides no guarantee of a payoff for women.

Promotion rate for men and women by hope for success

Personality traits reveal further gender patterns.

Men who display boldness and charisma, reflected by high extraversion, also experience a stronger likelihood of promotion. As do men who display the attitude that whatever happens to them in life is a result of their own choices and efforts, a trait we call "locus of control".

But again there is no link between any of these traits and the promotion prospects for women.

Collectively these findings point to a disturbing template for career success: be confident, be ambitious… and be male.

Be male and unafraid

This template for promotion also prescribes: don't show fear of failure. Among managers, though not among workers as a whole, fear of failure is linked to weaker job promotion prospects—but more profoundly for men than women.

This echoes the way society penalizes male leaders for revealing emotional weakness. Both men and women are hindered by gender norms.

So what's the harm in confidence training?

For women, it could do more harm than good. In a culture that does not value such attributes among women, contravening expected patterns carries risks.

'Fixing' women is itself a problem

Imploring women to adopt behaviors that characterize successful men creates a culture that paints women as "deficient" and devalues diverse working styles.

A fixation on fixing women—without proof it pays off—steers resources away from anti-discrimination initiatives that could actually make a difference.

In any case there is very little evidence confidence makes good workers. Overconfident workers can be liabilities.

Workplaces would be served better by basing their hiring and promotion decisions on competency and capability rather than confidence and charisma.

My study is one of a steadily growing number suggesting gender equity shouldn't be about changing women, it should be about changing workplaces.

Explore furtherWomen and men executives have differing perceptions of healthcare workplaces

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Measures for appointing more female professors prove effective

by Gertrud Lindner, ETH Zurich

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Since 2014, "equal! The Office of Equal Opportunity and Diversity" has documented the status of equal opportunities for men and women at ETH Zurich in an annual Gender Monitoring report. The latest report has been renamed "Equality Monitoring," as it also addresses the topic of diversity.

The recently published report, Equality Monitoring 2019/20, records an encouraging peak in the number of female professors at ETH Zurich. This leap forward owes much to the endeavors of the President and the Departments to appoint more women in a targeted way. In 2019, half of all new appointments to assistant professorships went to women, and 21 percent of permanent professorships. "I'm delighted to see that the bundle of measures we've taken is now having an impact on appointments. But these are just the first steps," says ETH Zurich President Joël Mesot.

Indeed, there's still much to be done: Women are still underrepresented at every academic career stage at ETH Zurich. For example, across all degree programs, just under a third of students are women—with only a tenth in some, and well over half in others. Only one in seven permanent professorships is filled by a woman.

Losses along the career path

Little has changed in the leaky pipeline. "The proportion of women declines from Master and doctorate level up to professor level, and this drop is more pronounced in some departments than others," says Renate Schubert, the ETH President's delegate for Equal Opportunities with responsibility for Equality Monitoring.

By means of the Gender Parity Index (GPI), ETH Zurich departments can be divided into three categories: those with a high overall proportion of women among students, doctoral students, academic staff, professors and technical-administrative staff, those with a medium and those with a very low overall proportion. Departments in the latter category, in particular, have now launched a raft of activities to ramp up the proportion of women. "We've noticed that the departments in the midfield are not really endeavoring to attract more women," states Schubert.

Even in departments with a high proportion of female Bachelor's and Master's students, the proportion decreases from doctoral level onwards. Nonetheless, Renate Schubert is optimistic. A growing number of female professors are proving that they are excellent and that a commitment to research, teaching and innovation is compatible with family life. This, she believes, will encourage young women to tackle the next academic level.

Diversity begets excellence

The authors of Equality Monitoring consider that a diversity strategy is crucial for universities, and it also fosters excellence. People working in a diverse research environment are more creative; they come up with unconventional research questions that generate innovative ideas, which are then transferred to practice. For students too, diverse learning environments are more stimulating and instructive, and therefore more productive than homogeneous ones.

But to achieve such diversity, the recruitment process and research and teaching evaluations must be designed to harness and develop the talent pool of very many, very different people. Maintaining and promoting diversity is costly and calls for considerable effort. It is something ETH Zurich has committed to with a number of initiatives, such as the Gender Action Plan, the Respect Code of Conduct, the Fix-the-Leaky-Pipeline Program, the creation of Gender and Diversity Advocates in appointment committees, and the implementation of the concerns of LGBTIQIA+ and other groups. These activities are to be consolidated and enhanced.

Painting a clearer picture

The Equality Monitoring report documents the degree of internationalization and the gender and age structure of ETH members. Other aspects of diversity, such as religion, sexual identity, or physical and mental disabilities, are sensitive data that is not currently collected at ETH Zurich. "It would be great if these aspects could be recorded in staff and student surveys in the future," says Renate Schubert. Such information would be provided voluntarily. For ultimately, "only if we have pertinent data can we grasp the crux of the diversity issue," she asserts.

Valuing diversity will create great opportunities, and ETH Zurich is right on track here. But there's still potential to increase diversity in all areas of the university; the Office of Equal Opportunity and Diversity will not be short of work any time soon.

Explore furtherTargets bring more women on boards, but they still don't reach the top

More information: ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/assoc … eport_19-20_engl.pdf

Provided by ETH Zurich

1 shares

Facebook

Twi

Young women who suffer a heart attack have worse outcomes than men

by European Society of Cardiology

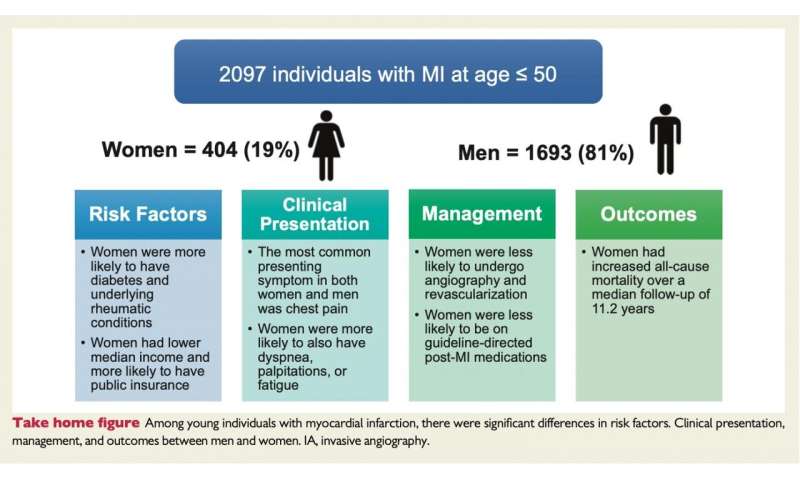

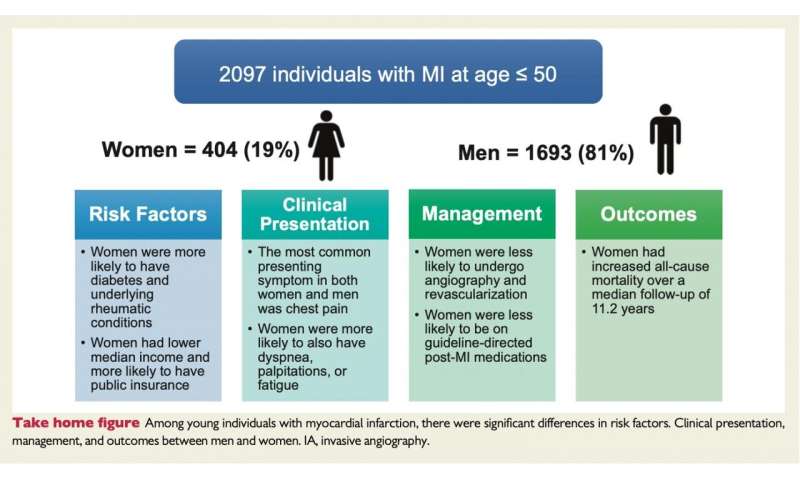

Figure showing risk factors, and clinical presentation, management and outcomes for men and women Credit: European Heart Journal

Figure showing risk factors, and clinical presentation, management and outcomes for men and women Credit: European Heart Journal

Women aged 50 or younger who suffer a heart attack are more likely than men to die over the following 11 years, according to a new study published today (Wednesday) in the European Heart Journal.

The study found that compared to men, women were less likely to undergo therapeutic invasive procedures after admission to hospital with a heart attack or to be treated with certain medical therapies upon discharge, such as aspirin, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors and statins.

The researchers, led by Ron Blankstein, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a preventive cardiologist at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, U.S., found no statistically significant differences between men and women for deaths while in hospital, or from heart-related deaths during an average of more than 11 years' follow-up. However, women had a 1.6-fold increased risk of dying from other causes during the follow-up period.

Prof. Blankstein said: "It's important to note that overall most heart attacks in people under the age of 50 occur in men. Only 19% of the people in this study were women. However, women who experience a heart attack at a young age often present with similar symptoms as men, are more likely to have diabetes, have lower socioeconomic status and ultimately are more likely to die in the longer term."

The researchers looked at 404 women and 1693 men who had a first heart attack (a myocardial infarction) between 2000 and 2016 and were treated at the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in the US. During a myocardial infarction the blood supply to the heart is blocked suddenly, usually by a clot, and the lack of blood can seriously damage the heart muscle. Treatments can include coronary angiography, in which a catheter is inserted into a blood vessel to inject dye so that an X-ray image can show if any blood vessels are narrowed or blocked, and coronary revascularisation, in which blood flow is restored by inserting a stent to keep the blood vessel open or by bypassing the blocked segment with surgery.

The median (average) age was 45 and 53% (1121) had ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), a type of heart attack where there is a long interruption to the blood supply caused by a total blockage of the coronary artery. Despite being a similar age, women were less likely than men to have STEMI (46.3% versus 55.2%), but more likely to have non-obstructive coronary disease. The most common symptom for both sexes was chest pain, which occurred in nearly 90% of patients, but women were more likely to have other symptoms as well, such as difficulty breathing, palpitations and fatigue.

Prof. Blankstein said: "Among patients who survived to hospital discharge, there was no significant difference in deaths from cardiovascular problems between men and women. Cardiovascular deaths occurred in 73 men and 21 women, 4.4% versus 5.3% respectively, over a median follow-up time of 11.2 years. However, when excluding deaths that occurred in hospital, there were 157 deaths in men and 54 death in women from all causes during the follow-up period: 9.5% versus 13.5% respectively, which is a significant difference, and a greater proportion of women died from causes other than cardiovascular problems, 8.4% versus 5.4% respectively, 30 women and 68 men. After adjusting for factors that could affect the results, this represents a 1.6-fold increased risk of death from any cause in women."

Women were less likely to undergo invasive coronary angiography (93.5% versus 96.7%) or coronary vascularisation (82.1% versus 92.6%). They were less likely to be discharged with aspirin (92.2% versus 95%), beta-blockers (86.6% versus 90.3%), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) or angiotensin receptor blockers (53.4% versus 63.7%) and statins (82.4% versus 88.4%).

The study is the first to examine outcomes following heart attack in young men and women over such a long follow-up period. It shows that even after adjusting for differences in risk factors and treatments, women are more likely to die from any cause in the longer term. The researchers are unsure why this could be. Despite finding no significant difference in the overall number of risk factors, they wonder whether some factors, such as smoking, diabetes and psychosocial risk factors might have stronger adverse effects on women than on men, which overcome the protective effect of the estrogen hormone in women.

Prof. Blankstein added: "As fewer women had STEMI and more had non-obstructive myocardial infarction, they are less likely to undergo coronary revascularisation or to be given medications such as dual anti-platelet therapy, which is essential after invasive heart procedures. Also, the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease may raise uncertainty regarding the diagnosis and whether such individuals truly had a myocardial infarction or have elevated enzymes due to other causes.

"While further studies will be required to evaluate the underlying reasons for these differences, clinicians need to evaluate and, if possible treat, all modifiable risk factors that may affect deaths from both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular events. This could lead to improved prevention, ideally before, but in some cases, after a heart attack. We plan further research to assess underlying sex-specific risk factors that may account for the higher risk to women in this group, and which may help us understand why they had a heart attack at a young age."

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Marysia Tweet, assistant professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Minnesota, U.S., writes that "it is essential to aggressively address traditional cardiovascular risk factors in young AMI [acute myocardial infarction] patients, especially among young women with AMI and a high burden of comorbidities. Assessing clinical risk and implementing primary prevention is imperative, and non-traditional risk factors require attention, although not always addressed". Examples include a history of pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes and ovary removal and she points out that depression was twice as common among women in this study compared to men; "young women with depression are six times more likely to have coronary heart disease than women without depression."

She concludes: "This study . . . demonstrates the continued need—and obligation—to study and improve the incidence and mortality trajectory of cardiovascular disease in the young, especially women. We can each work towards this goal by increasing awareness of heart disease and 'heart healthy' lifestyles within our communities; engaging with local policy makers, promoting primary or secondary prevention efforts within our clinical practices; designing studies that account for sex differences; facilitating recruitment of women into clinical trials; requesting sex-based data when reviewing manuscripts; and reporting sex differences in published research."

Limitations of the research include: the researchers were unable to account for some potential factors that might be associated with patient outcomes or management, such as patient preferences or psychosocial factors; there were no data about whether patients continued to take their prescribed medications, or on sex-specific risk factors, such as problems relating to pregnancy; the small number of women in the study may have affected the results; and deaths before reaching hospital were not counted.

Explore further Study provides hope for young women after heart attack

More information: Ersilia M DeFilippis et al, Women who experience a myocardial infarction at a young age have worse outcomes compared with men: the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI registry, European Heart Journal (2020).

First results from new study examining the impact of COVID-19 on working-class women in the UK published today

by Sheila Kiggins, University of Warwick

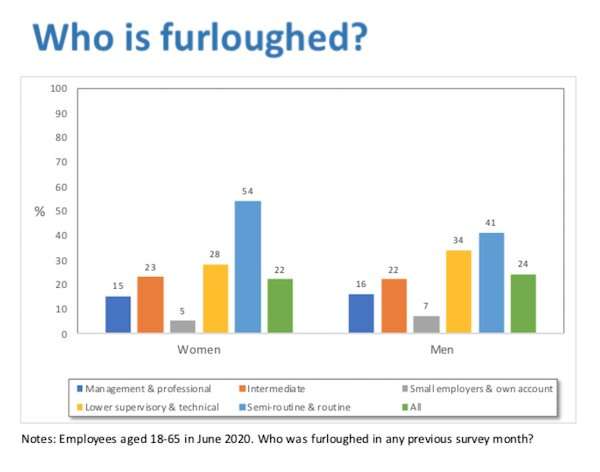

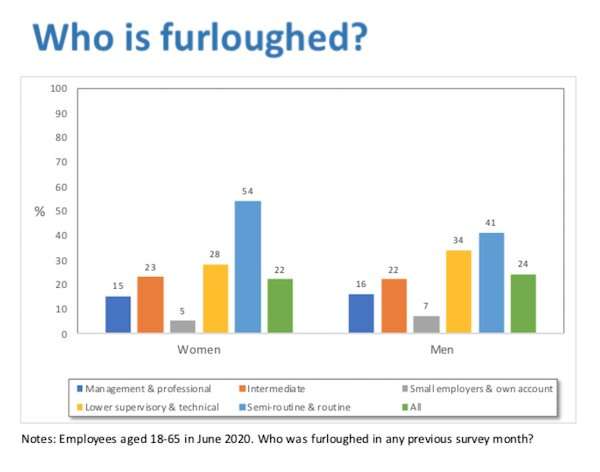

Working class women have borne the brunt of the cuts to working hours as employers struggle to ride out the pandemic, according to new findings published today by social inequality researchers.

Almost half of working class women (43 percent) did no hours of work in April compared to just 20 percent of women in professional or managerial roles. By June fewer than half of all women in work (48 percent) were still working full-time hours.

Professor Tracey Warren (University of Nottingham) and Professor Clare Lyonette (University of Warwick) are working with the Women's Budget Group to understand how working-class women are responding in real-time to the pressures imposed by the virus.

Today's briefing paper—"Carrying the work burden of the COVID-19 pandemic: working class women in the UK: Employment and Mental Health"—focuses on patterns of employment and mental health in the first three months of lockdown, as revealed by data from the monthly Understanding Society COVID-19 UK survey, and explores to what extent the experience of working class women differs from middle class women and from men.

The first wave of results reveals that many more working class women than men or women in middle class jobs saw their hours cut to zero in the first months of lockdown, with potentially severe financial consequences.

Those working class women still at work are far less likely to be working from the relative safety of home than women in managerial or professional roles—80 percent of working class women said they were "never" working from home in June.

Working class women are also the most likely to be keyworkers in roles with close contact with customers, clients and patients—such as undertaking personal care in care homes and looking after children—with greater potential to be exposed to the virus.

Professor Tracey Warren said, "Our research shows that working-class women are disproportionately furloughed compared to men and other women—and if they are working, there is a greater potential for women to be exposed to health risks due to the nature of their roles as key workers.

"We know these women also care for children and relatives, so with the added stress of worrying about if they were to contract coronavirus or how their household will cope with the loss of 20% of their salary due to furlough, it is no wonder their mental health is suffering."

Professor Lyonette added, "Although the very high levels of psychological distress among working class women in particular have dropped slightly since lockdown restrictions were lifted, they are still much higher than before the pandemic.

"The government announced yesterday a 3-tier system of local restrictions for England, with many working class areas included in the higher tier groups. The effects of a Tier 3 lockdown, could be far-reaching and extremely damaging for working class women who provide vital work, both paid and unpaid."

Dr. Mary-Ann Stephenson, director of the UK Women's Budget Group, said, "Working class women have been more likely to be furloughed and are at high risk of redundancy as the furlough scheme is rolled back.

"The Government's national replacement scheme creates little incentives for employers to keep these women on. Low paid women in areas where lock down is being re-imposed will be entitled to additional help if they are in a closed down sector, but for workers on the minimum wage or just above, two thirds of current earnings is likely to mean poverty.

"At the same time the increase in universal credit introduced at the start of lockdown is due to end in March so low paid workers and those who lose their jobs will be worse off. If the Government is serious about building back better, it needs to take urgent action to protect the employment and incomes of working class women."

Key findings:

Keyworkers

60% of women in semi-routine and routine jobs are keyworkers, in roles that have a high level of social contact.

Keyworking is highest among working class women—60% of women in semi-routine and routine jobs are keyworkers

Women keyworkers are concentrated in face-to-face roles such as health and social care, child care and education. These are roles with high levels of social interaction and possible virus exposure.

Working from Home

Working class women are very unlikely to be working from home:

Only 9% of working class women said they were "always" working from home in June, compared to the average for all women of 30%. 80% were working outside of the home.

44% of women in professional or managerial roles said they "always" worked from home in June.

Furlough and working hours

Working class women were more likely to be furloughed than women in middle class jobs and men.

Almost half of working class women (43%) did no hours of work in April compared to just 20% of women in professional or managerial roles.

In April less than half of all women in work (43%) were working full-time hours. 58% of men were still in full time work.

Mental heath

Across all classes, more women than men reported feeling psychological distress.

Levels of distress for men and women dropped between April and June

In April 41% of working class women were experiencing distress, the highest proportion across classes. This fell in June to 30%.

Future Briefing Notes will explore housework and childcare, and changes in employment and financial impacts.

Explore further COVID-19 has hit women hard, especially working mothers

More information: warwick.ac.uk/newsandevents/pr … _note_1_13-10-20.pdf

Provided by University of Warwick

Maltreatment tied to higher inflammation in girls

by Allyson Mann, University of Georgia

Katherine Ehrlich. Credit: University of Georgia

New research by a University of Georgia scientist reveals that girls who are maltreated show higher levels of inflammation at an early age than boys who are maltreated or children who have not experienced abuse. This finding may forecast chronic mental and physical health problems in midlife.

Led by psychologist Katherine Ehrlich, the study is the first to examine the link between abuse and low-grade inflammation during childhood.

Inflammation plays a role in many chronic diseases of aging—diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, obesity—as well as mental health outcomes, and the findings suggest that maltreatment's association with inflammation does not lie dormant before emerging in adulthood. Instead, the study shows that traumatic experiences have a much more immediate impact.

"We and others have speculated that there's something about the immune system that's getting calibrated, particularly during childhood, that might be setting people up on long-term trajectories toward accelerated health problems," said Ehrlich, assistant professor in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. "What I'm struck by is just how early in development we can see these effects. What our study highlights is that, even as early as childhood, we can see that a substantial portion of the children have levels of inflammation that the American Heart Association considers 'moderate risk' for heart disease. This is concerning from a public health perspective and suggests that these children may be at risk for significant health problems at an earlier age than their nonmaltreated peers."

Participants in the study included 155 children aged 8-12 from low-income backgrounds who attended a weeklong day camp. The sample was racially diverse and included maltreated and nonmaltreated children.

Researchers captured detailed information on children's exposure to abuse by utilizing Department of Human Services records about maltreatment experiences in families. The children-documented experiences included neglect (55%), emotional maltreatment (67%), physical abuse (35%) and sexual abuse (8%). Many children experienced more than one type of abuse, and 35% of children experienced abuse across multiple developmental periods.

The team measured five biomarkers of low-grade inflammation using non-fasting blood samples from the children.

Results revealed that childhood maltreatment—for girls—was associated with higher levels of low-grade inflammation in late childhood. Girls who had been abused over multiple periods or had multiple kinds of exposures had the highest levels of inflammation. Girls' greatest risk for elevated inflammation emerged when they were abused early in life, before the age of 5.

For boys in the study, exposure to maltreatment was not reflected in higher levels of inflammation, but Ehrlich cautioned against drawing conclusions without additional research targeted to boys.

"One question is, are these variations due to developmental timing differences?" she said. "We know that girls mature faster than boys in terms of their biological and physical development. If we tested these same boys two years later, would we find the same patterns of inflammation that we found for the girls?"

Explore further

Major study shows waterbirths as safe as traditional births

by Allina Health

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

A new U.S. study of waterbirths found that hospital-based births involving water immersion had no higher risk of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or special care nursery admission than comparable deliveries in the control group without water immersion. The primary purpose of the study is to address the lack of methodologically sound research regarding maternal and neonatal outcomes for waterbirths. The study has been published in the journal, Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the professional organization that sets standards for obstetric practice, previously concluded that water immersion during the first stage of labor (when a woman is in labor but is not fully dilated) is safe for women with full-term, uncomplicated pregnancies. In fact, water immersion during labor provides benefits of pain relief, reduced analgesic need, shorter labor, and increased patient satisfaction. However, ACOG also identified an absence of well-designed studies to aid in the determination of the risks and benefits of water immersion during the second stage of labor (when a woman is fully dilated and can actively push during contractions).

"This study demonstrates that the system we put in place provides waterbirth in the context of a strong clinical program that ensures safety," said Dr. Lisa Saul, a perinatologist, president of Allina Health's Mother Baby service line and study coauthor. "As a health system, we want to offer women as many choices as possible to help them manage pain during labor. Our primary focus is always on the safety of mothers and newborns so we need to ensure we are basing our practices on the best evidence available."

In order to address the lack of quality research on waterbirth outcomes during the second stage, Allina Health led a multi-site study. The study includes data from 583 births over 4-years (2014-2018) from eight hospitals in the Allina Health and HealthPartners systems and a matched comparison group of 583 births to women who met the criteria for waterbirth but did not have water immersion during labor. As waterbirth has become more popular in the United States, it is important for practitioners to be able to inform their practices and guidelines in the context of U.S. clinical standards. Prior to this study, there were only a few studies examining waterbirth outcomes in the US, and those mostly focused on deliveries outside of a hospital setting (such as home births or birth centers).

Prior studies on waterbirths, conducted primarily in Europe, had varied clinical protocols that were often not described making it hard to understand how outcomes might be affected by clinical protocols. Additionally, prior studies often lacked strong study designs and thus were subject to potential sources of bias. The current study brings new methodological strengths not found in many prior studies, such as a large sample size and matching techniques used to ensure comparability between the women delivering in water and the comparison group. In alignment with ACOG recommendations, Allina and HealthPartners, established rigorous protocols for candidate selection, tub maintenance and cleaning, monitoring of women and fetuses, and moving women from tubs if maternal or fetal concerns or complications develop. The sites also developed rigorous training program to credential providers for water immersion deliveries, and a quality assurance process.

"Women and families deserve safe and evidence based care regardless of their birth preferences," said Kathrine Simon, study coauthor, a certified nurse midwife and Midwifery Lead for Allina Health who conducts provider training for water immersion deliveries. "This study demonstrates that waterbirth is a safe option for women during labor in addition to supporting provider and nursing training and support."

The study found that the proportion of deliveries with NICU or special care nursery admission was significantly lower for women with second-stage immersion (2.9%) than the control group (8.3%). There was no difference in NICU or special care nursery admissions for deliveries with first-stage immersion only. Of the secondary neonatal outcomes examined (i.e., respiratory distress, anemia, sepsis, asphyxia, or death), there were no significant differences between the water immersion groups and matched deliveries in the control group.

A possible benefit identified in the study for women was reduced likelihood of lacerations during delivery. Women in the second stage water immersion group were half as likely as women in the comparison group to experience any perineal lacerations. This measure did not differ for women who had first-stage only immersion cases.

"Women are often grateful for the opportunity for labor and birth in the water. Many are surprised by the lack of pelvic pressure and a sense of the baby gliding out," said Simon. "This study confirms that waterbirths, conducted in alignment with a strong clinical protocol, are at least as safe as traditional birthing methods."

Explore further Birthing pool not the place to deliver, new guidelines say

More information: Abbey C. Sidebottom et al, Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes in Hospital-Based Deliveries With Water Immersion, Obstetrics & Gynecology (2020). DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003956

Journal information: Obstetrics and Gynecology , Obstetrics & Gynecology

Provided by Allina Health

Figure showing risk factors, and clinical presentation, management and outcomes for men and women Credit: European Heart Journal

Figure showing risk factors, and clinical presentation, management and outcomes for men and women Credit: European Heart Journal