THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BEING

A CUSTODIAN OR A JANITOR

by Kim Tucker Campo, New York Institute of Technology

by Kim Tucker Campo, New York Institute of Technology

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

How can consumers be encouraged to take better care of public goods and resources? That's the question posed in a new research paper co-authored by Colleen P. Kirk, D.P.S., associate professor of marketing at New York Institute of Technology, in the Journal of Marketing.

"Caring for the Commons: Using Psychological Ownership to Enhance Stewardship Behavior for Public Goods" aims to help solve the "tragedy of the commons," the idea that when goods or resources are shared by many owners they are subject to abuse or neglect.

Sadly, the tragedy of the commons can be seen in many public spaces, such as cemeteries, public housing, fishing areas, and beaches, and has contributed to a number of environmental challenges. One commonly cited environmental issue includes ocean pollution. Because ocean waters are shared by many different nations no single authority has the power to pass laws that protect the entire ocean. Instead, nations manage and protect ocean resources along their coastlines, leaving the much larger shared waters vulnerable to contamination.

Citing available studies on the tragedy of the commons, Kirk joins Joann Peck, Ph.D., of Wisconsin-Madison School of Business; Andrea Luangrath, Ph.D., of the University of Iowa; and Suzanne Shu, Ph.D., of Cornell University in hypothesizing that increased feelings of ownership towards a public good can help ensure that individuals do their part.

Putting their theory to the test

The researchers manipulated scenarios in public settings to encourage visitors to view the spaces as their own, rather than as a shared commodity. In each scenario, the investigators found that increasing psychological ownership enhanced stewardship, causing participants to become more likely to take direct action to care for that setting, such as picking up trash, or financial stewardship, such as donating money.

For example, the researchers manipulated psychological ownership of a lake by asking a randomized group of kayak renters to think of and write down a nickname for the lake before renting their boats. Unbeknownst to the kayakers, the researchers had planted anchored floating trash in the lake to test whether naming the lake would create an increased feeling of ownership. Compared to the control group, kayakers who were not asked to name the lake, the "namers" were more likely to do their part in trying to pick up the trash, with 41 percent attempting to remove the planted litter.

In another scenario, study participants were asked to imagine that they were taking a walk in a hypothetical park called Stoneview Park. Researchers showed the control group a park entrance sign that read the generic message, "Welcome to the park." In contrast, the experimental group was shown a sign reading, "Welcome to YOUR park." Each group of "walkers" then completed a survey on how likely they were to remove litter or donate to park maintenance efforts. Once again, when compared to the control group, those exposed to the psychological ownership tactics (YOUR park group) felt a greater need to care for and contribute to maintaining the public space.

A third scenario tested yet another psychological ownership tactic aimed at cultivating stewardship. Cross country skiers and snowshoers at a public park ski rental were asked to plan a route prior to their outing. Following the completion of the park's standard liability waiver, an employee offered them a map, obtained their shoe size, and, in the control group (the "non-planners"), went on to retrieve the ski equipment. However, in the experimental group, before retrieving the skis or snowshoes, the employee asked the renters to plan a route they might take on the map. All renters were then charged for their ski equipment and asked whether they would like to add a dollar to the rental fee to help the park. Donations indicated that individuals who planned their route in advance were more likely to chip in. In addition, a participant survey also revealed that those asked to plan their route were more likely to feel ownership, volunteer, donate in the future, and promote the park to others using social media. The researchers believe that because these skiers played an active role in shaping their experience, they may have felt a greater sense of connection to the park.

Kirk, who has published significant research on psychological ownership and an op-ed in Harvard Business Review, believes the findings can assist marketers in conservation efforts.

"Maintaining the natural environment is a pressing issue facing our planet, and has become more challenging during the pandemic as park services are reduced while the number of people spending time outside has increased," she notes. "Researchers have previously shown that eliciting feelings of ownership in consumers, even in the absence of legal ownership, induces them to value a product more highly. In this research, we document, through a variety of experimental studies in the field and in the laboratory, that individual psychological ownership also motivates caring behaviors for a public good, such as picking up trash from a lake or donating time or money to a park. We encourage marketers and environmentalists alike to reflect on these findings when considering ways to maintain public spaces."

Why people go into debt: The money isn't really theirs

More information: Joann Peck et al, Caring for the Commons: Using Psychological Ownership to Enhance Stewardship Behavior for Public Goods, Journal of Marketing (2020). DOI: 10.1177/0022242920952084

Journal information: Journal of Marketing

Provided by New York Institute of Technology

How can consumers be encouraged to take better care of public goods and resources? That's the question posed in a new research paper co-authored by Colleen P. Kirk, D.P.S., associate professor of marketing at New York Institute of Technology, in the Journal of Marketing.

"Caring for the Commons: Using Psychological Ownership to Enhance Stewardship Behavior for Public Goods" aims to help solve the "tragedy of the commons," the idea that when goods or resources are shared by many owners they are subject to abuse or neglect.

Sadly, the tragedy of the commons can be seen in many public spaces, such as cemeteries, public housing, fishing areas, and beaches, and has contributed to a number of environmental challenges. One commonly cited environmental issue includes ocean pollution. Because ocean waters are shared by many different nations no single authority has the power to pass laws that protect the entire ocean. Instead, nations manage and protect ocean resources along their coastlines, leaving the much larger shared waters vulnerable to contamination.

Citing available studies on the tragedy of the commons, Kirk joins Joann Peck, Ph.D., of Wisconsin-Madison School of Business; Andrea Luangrath, Ph.D., of the University of Iowa; and Suzanne Shu, Ph.D., of Cornell University in hypothesizing that increased feelings of ownership towards a public good can help ensure that individuals do their part.

Putting their theory to the test

The researchers manipulated scenarios in public settings to encourage visitors to view the spaces as their own, rather than as a shared commodity. In each scenario, the investigators found that increasing psychological ownership enhanced stewardship, causing participants to become more likely to take direct action to care for that setting, such as picking up trash, or financial stewardship, such as donating money.

For example, the researchers manipulated psychological ownership of a lake by asking a randomized group of kayak renters to think of and write down a nickname for the lake before renting their boats. Unbeknownst to the kayakers, the researchers had planted anchored floating trash in the lake to test whether naming the lake would create an increased feeling of ownership. Compared to the control group, kayakers who were not asked to name the lake, the "namers" were more likely to do their part in trying to pick up the trash, with 41 percent attempting to remove the planted litter.

In another scenario, study participants were asked to imagine that they were taking a walk in a hypothetical park called Stoneview Park. Researchers showed the control group a park entrance sign that read the generic message, "Welcome to the park." In contrast, the experimental group was shown a sign reading, "Welcome to YOUR park." Each group of "walkers" then completed a survey on how likely they were to remove litter or donate to park maintenance efforts. Once again, when compared to the control group, those exposed to the psychological ownership tactics (YOUR park group) felt a greater need to care for and contribute to maintaining the public space.

A third scenario tested yet another psychological ownership tactic aimed at cultivating stewardship. Cross country skiers and snowshoers at a public park ski rental were asked to plan a route prior to their outing. Following the completion of the park's standard liability waiver, an employee offered them a map, obtained their shoe size, and, in the control group (the "non-planners"), went on to retrieve the ski equipment. However, in the experimental group, before retrieving the skis or snowshoes, the employee asked the renters to plan a route they might take on the map. All renters were then charged for their ski equipment and asked whether they would like to add a dollar to the rental fee to help the park. Donations indicated that individuals who planned their route in advance were more likely to chip in. In addition, a participant survey also revealed that those asked to plan their route were more likely to feel ownership, volunteer, donate in the future, and promote the park to others using social media. The researchers believe that because these skiers played an active role in shaping their experience, they may have felt a greater sense of connection to the park.

Kirk, who has published significant research on psychological ownership and an op-ed in Harvard Business Review, believes the findings can assist marketers in conservation efforts.

"Maintaining the natural environment is a pressing issue facing our planet, and has become more challenging during the pandemic as park services are reduced while the number of people spending time outside has increased," she notes. "Researchers have previously shown that eliciting feelings of ownership in consumers, even in the absence of legal ownership, induces them to value a product more highly. In this research, we document, through a variety of experimental studies in the field and in the laboratory, that individual psychological ownership also motivates caring behaviors for a public good, such as picking up trash from a lake or donating time or money to a park. We encourage marketers and environmentalists alike to reflect on these findings when considering ways to maintain public spaces."

Why people go into debt: The money isn't really theirs

More information: Joann Peck et al, Caring for the Commons: Using Psychological Ownership to Enhance Stewardship Behavior for Public Goods, Journal of Marketing (2020). DOI: 10.1177/0022242920952084

Journal information: Journal of Marketing

Provided by New York Institute of Technology

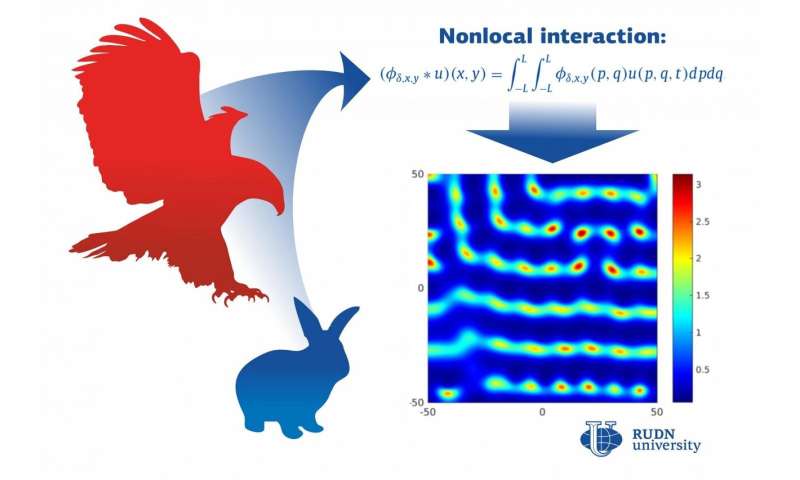

The traditional mathematical model of predator-prey relations in the wild does not take into account indirect nonlocal interactions. However, according to a mathematician from RUDN University, they affect the dynamics of predators and prey in a system, and the nature of this effect is sensitive to the initial conditions. Credit: RUDN University

The traditional mathematical model of predator-prey relations in the wild does not take into account indirect nonlocal interactions. However, according to a mathematician from RUDN University, they affect the dynamics of predators and prey in a system, and the nature of this effect is sensitive to the initial conditions. Credit: RUDN University