CROC DRONES

Cutting-edge computer vision technologies help detect threatsby University of Technology, Sydney

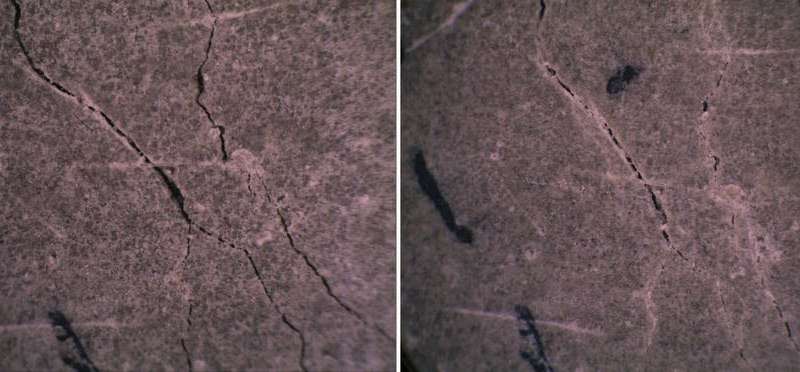

Credit: University of Technology Sydney (UTS)

It's been called "the future of warfare." Off-the-shelf unmanned aerial systems (UAS), carrying a payload of explosives or biological material, flown by terrorists or enemy armed forces into a crowded building or military base.

Now the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and Sydney ASX-listed defense tech company DroneShield have produced next-generation drone technology to better identify threats from these aggressive UAS.

In a partnership funded by the NSW and Australian Governments, UTS and DroneShield—an Australian developer of counter-UAS solutions—have produced an optical system for detection, identification and tracking of fast-moving threats such as nefarious UAS, comprised of a camera and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN).

UTS and DroneShield began working together in October 2019—just a month after one of the most recent examples of aggressive use of drones when the oil facilities at Abqaiq–Khurais in Saudi Arabia were attacked by a swarm of UAS.

The new technology was recently demonstrated at Sydney Science Park.

The NSW Minister for Jobs and Western Sydney, Stuart Ayres, said the State Government was committed to helping small businesses grow through programs such as the NSW Government-funded Defense Innovation Network (DIN).

"The collaboration between DroneShield and UTS is exactly the type of industry/university partnership the NSW Government is committed to expanding," he said. "This is a key part of how the Government is supporting growth in jobs in NSW in areas such as defense tech. And seeing the technology here in Western Sydney, just outside of the future Aerotropolis, gives us a glimpse into the type of R&D and industry activity that will take place out here in the future."

UTS Vice-Chancellor Attila Brungs said this project is a great example of the types of partnerships UTS is committed to.

"For UTS to do what we do best—develop and translate world-leading research for practical application by industry—government support is critical. Having both the NSW and Australian Governments invest in this partnership, which has produced defense technology that can be used around the world, shows what can happen when universities, government and industry work together. UTS is committed to developing more industry co-working spaces, both on our home campus in the Sydney CBD, and here in Western Sydney at the Sydney Science Park with Celestino," Professor Brungs said.

Project lead and Co-Director of UTS Intelligent Drone Lab (IDL) Dr. Nabin Sharma said UTS has both expertise and experience in collaborating with industry partners to develop and deliver innovative vision systems for UAVs. This is seen in the multi-award-winning SpotterAI suite of drones (SharkSpotter, CrocSpotter) which identify particular threats to humans and are used to safeguard swimmers, fishers and other marine species.

"We are using CNNs and deep learning to provide a solution for DroneShield to identify drones which could be of potential threat," Dr. Sharma said. "The algorithm enables the vision system to see what's happening, to collate data and process it for ultra-fast image recognition and analysis. This delivers a speedy and efficient assessment of a threat and the decision-making in response to it. The system is able to detect different types of drones and check if there is a payload," he said.

Oleg Vornik, DroneShield's CEO, said "We are pleased to add this ground-breaking technology to our systems, enabling our customers a unique camera-based detection, ID and tracking of improvised threats such as UAS. This project has been a great example of collaboration between an Australian defense SME and an educational institution, promoting development of world leading, cutting-edge defense technologies right here in Sydney."

Explore further CrocSpotter app uses AI for detection

It's been called "the future of warfare." Off-the-shelf unmanned aerial systems (UAS), carrying a payload of explosives or biological material, flown by terrorists or enemy armed forces into a crowded building or military base.

Now the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and Sydney ASX-listed defense tech company DroneShield have produced next-generation drone technology to better identify threats from these aggressive UAS.

In a partnership funded by the NSW and Australian Governments, UTS and DroneShield—an Australian developer of counter-UAS solutions—have produced an optical system for detection, identification and tracking of fast-moving threats such as nefarious UAS, comprised of a camera and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN).

UTS and DroneShield began working together in October 2019—just a month after one of the most recent examples of aggressive use of drones when the oil facilities at Abqaiq–Khurais in Saudi Arabia were attacked by a swarm of UAS.

The new technology was recently demonstrated at Sydney Science Park.

The NSW Minister for Jobs and Western Sydney, Stuart Ayres, said the State Government was committed to helping small businesses grow through programs such as the NSW Government-funded Defense Innovation Network (DIN).

"The collaboration between DroneShield and UTS is exactly the type of industry/university partnership the NSW Government is committed to expanding," he said. "This is a key part of how the Government is supporting growth in jobs in NSW in areas such as defense tech. And seeing the technology here in Western Sydney, just outside of the future Aerotropolis, gives us a glimpse into the type of R&D and industry activity that will take place out here in the future."

UTS Vice-Chancellor Attila Brungs said this project is a great example of the types of partnerships UTS is committed to.

"For UTS to do what we do best—develop and translate world-leading research for practical application by industry—government support is critical. Having both the NSW and Australian Governments invest in this partnership, which has produced defense technology that can be used around the world, shows what can happen when universities, government and industry work together. UTS is committed to developing more industry co-working spaces, both on our home campus in the Sydney CBD, and here in Western Sydney at the Sydney Science Park with Celestino," Professor Brungs said.

Project lead and Co-Director of UTS Intelligent Drone Lab (IDL) Dr. Nabin Sharma said UTS has both expertise and experience in collaborating with industry partners to develop and deliver innovative vision systems for UAVs. This is seen in the multi-award-winning SpotterAI suite of drones (SharkSpotter, CrocSpotter) which identify particular threats to humans and are used to safeguard swimmers, fishers and other marine species.

"We are using CNNs and deep learning to provide a solution for DroneShield to identify drones which could be of potential threat," Dr. Sharma said. "The algorithm enables the vision system to see what's happening, to collate data and process it for ultra-fast image recognition and analysis. This delivers a speedy and efficient assessment of a threat and the decision-making in response to it. The system is able to detect different types of drones and check if there is a payload," he said.

Oleg Vornik, DroneShield's CEO, said "We are pleased to add this ground-breaking technology to our systems, enabling our customers a unique camera-based detection, ID and tracking of improvised threats such as UAS. This project has been a great example of collaboration between an Australian defense SME and an educational institution, promoting development of world leading, cutting-edge defense technologies right here in Sydney."

Explore further CrocSpotter app uses AI for detection

Provided by University of Technology, Sydney