Our Vaccine Infrastructure Needs a Radical Overhaul

Decades-long funding cuts for pandemic preparedness hamper coordinated distribution and equitable access. We must reimagine how to make life-saving vaccines available to everyone.

November 14, 2020 Ravi Gupta BOSTON REVIE

Nearly a year into a pandemic that has killed more than a million people and laid waste to both public health systems and the global economy, many have turned their hopes to a vaccine. Optimism has been buoyed by the historic pace of development of multiple COVID-19 vaccine candidates and the recent news that Pfizer, in partnership with the small company BioNTech, has reported preliminary data on a vaccine candidate showing 90 percent effectiveness. The arrival of a vaccine in the next few months would be a remarkable feat, but fundamental questions—beyond basic assurances of safety and efficacy—remain. Will there be enough doses, and who will get them?

This is not the first time we face questions of equitably deploying a vaccine during an outbreak. Eleven years ago, as the H1N1 virus swept across the United States and 73 other countries, the World Health Organization declared the first pandemic in over forty years. H1N1 seemed deadlier and more transmissible than seasonal influenza. Recollections of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic’s colossal death toll occupied the collective psyche. An H1N1 vaccine seemed essential to prevent history from repeating, much as a COVID-19 vaccine does now.

Development of an H1N1 vaccine progressed rapidly, in large part due to existing technology and regulatory systems for seasonal influenza vaccines. But avoiding preventable deaths required ensuring the vaccine’s prompt manufacturing and equitable distribution within the U.S. and across the world. Manufacturing delays led to shortages that complicated an already halting domestic distribution plan, and by the time the vaccine supply increased, the pandemic had waned. All told, 90 of 162 million doses were utilized in the United States. The rest were donated to other countries (after broken pledges to do so earlier) or simply thrown away. A truth was illuminated that persists today: the prevailing system of vaccine production and distribution is not designed to promote equitable access.

Much has changed since the H1N1 pandemic. Technological platforms have advanced considerably. International institutions have forged partnerships to prioritize therapeutic and vaccine candidates. Financing of vaccine development has evolved, with the creation of non-profit entities like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).

Yet much remains the same. Vaccine manufacturing remains unprepared for surges and without a global entity charged with centralized financing. International legal agreements ensuring equitable access are non-enforceable. The international hoarding and price gouging for personal protective equipment early in this pandemic are harbingers for vaccine maldistribution to the highest bidder. Within the United States, in particular, decades-long funding cuts for pandemic preparedness and public health hamper coordinated distribution for efficient access. Surviving a pandemic requires extraordinary movement on these issues. We must reimagine how to make life-saving vaccines available to everyone, for pathogens both new and old.

Deployment of H1N1 vaccines faced a bottleneck that we still face today: insufficient manufacturing capacity. Coordination between manufacturers, government agencies, and universities in multiple continents led to the FDA approval of four H1N1 vaccines within six months. But enough vaccine could simply not be produced in time. Years of industry consolidation due to limited profits from vaccine development had left just three companies available to manufacture the majority of global influenza vaccines. Manufacturing capacity was dependent on well-established but time-consuming and unpredictable egg-based technology from World War II, while production lines were already occupied with seasonal flu vaccines.

Today, the leading COVID-19 vaccine candidates rely on novel technology that hasn’t yet been deployed at scale. These platforms have the potential for faster production, but they will likely face unforeseen difficulties. Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, for example—like Pfizer and BioNTech’s—require temperatures as low as -94 degrees Fahrenheit to maintain stability, whereas H1N1 vaccines were easily stored in small fridges. COVID-19 vaccines will likely require two doses, doubling the total number needed, while H1N1 vaccines required just one.

At the root of the manufacturing problem is a near exclusive reliance on the private sector, which has limited incentives for preemptive investment. As a result, funding hastily flows from public coffers to private companies to bolster manufacturing capacity once an outbreak has already begun. During the H1N1 pandemic, the U.S. government awarded contracts to manufacturers to upgrade their facilities and start vaccine production. With COVID-19, we’ve seen a dizzying number of agreements between governments and private companies to scale production, among them agreements facilitated by the U.S. public-private partnership Operation Warp Speed.

Of course, it isn’t feasible to expect immediate global availability of sixteen billion doses. But a reactive approach to vaccine production grounded in a market-based logic de-emphasizes the long-term readiness and preparation needed for efficient and equitable deployment of a vaccine in a pandemic.

We need an alternative approach that centers on maintaining public manufacturing facilities to respond to the acute needs of an outbreak before it happens. In the wake of H1N1, the U.S. government invested in developing four manufacturing sites in concert with a university and private companies. But these facilities lacked sustained development and were unequipped for rapid, mass production during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the past few months, substantial Operation Warp Speed funds have gone to the Texas A&M University System and Emergent Solutions to partner with vaccine developers to manufacture doses. It remains to be seen whether an injection of funds at this moment will help construct and maintain a sustainable, public manufacturing sector for future outbreaks. We should recognize that preparedness is not a novel concept; epidemiologists and national security experts alike have been arguing about its importance for decades. Twenty years ago, science journalist Laurie Garrett characterized the collapse of global health infrastructure as a “betrayal of trust.” We are witnessing the effects of that betrayal today.

An initial vaccine shortfall necessitates thoughtful distribution to enable equitable global access. The H1N1 pandemic exposed glaring disparities between rich and poor nations in procuring vaccines. Before a pandemic was even declared, developed countries placed large advance orders with manufacturers. The World Health Organization secured small donation commitments from developed countries and manufacturers for developing countries. The United States pledged to donate 10 percent of its vaccines, but as H1N1 cases and vaccine shortages increased, it rescinded its offer. Canada and Australia permitted exports from their domestic manufacturers only after their own citizens were immunized. Eventually, 78 million doses—an inadequate amount to begin with—were donated to 77 countries, but the worst of the pandemic had already passed.

Fears of such vaccine nationalism—countries prioritizing their own populations at the expense of a globally coordinated strategy—have materialized in the current pandemic, too. Multilateral advance market commitments, a form of payment to manufacturers predicated on proof of a successful vaccine, are meant to equitably allocate vaccines among countries. Various advance market commitments (AMCs) have been proposed and created for COVID-19 vaccines, including $2 billion in urgent funding specifically for low- and middle-income country AMCs as part of an effort by the COVAX facility—an international collaboration between the World Health Organization, CEPI, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance—to deliver 2 billion doses globally by the end of 2021. (COVAX estimates the total cost for delivering on its plan to be $18.1 billion.)

Though advance market commitments such as the Gavi-led pneumococcal vaccine fund have been used successfully (though not without criticism of its price and lack of transparency), COVID-19 is the first test of whether they can function during a pandemic affecting wealthy and poor countries simultaneously. Bilateral agreements between manufacturers and individual wealthy countries who seek to guarantee their own supply have undermined the COVAX advance market commitment and precluded efficient and equitable global allocation of potential vaccines. Pfizer and BioNTech, for instance, have yet to sign any agreements to provide developing countries with their vaccine, and the majority of their initial supply has already been claimed by wealthier countries.

An enforceable trade and investment agreement is needed. Sadly, simply beginning these discussions seems too advanced when the Trump administration has amazingly sought to withdraw funding and support from the World Health Organization and refused to join COVAX—even though more than 150 countries have joined.

The absence of a global strategy encompassing high-risk populations is morally reprehensible, but it also makes no biological or economic sense. The virus will continue to spread without coordination for vaccine allocation based on need. Elements of international integration and global travel that accelerated this pandemic will perpetuate transmission. Global trade and tourism will further suffer. COVID-19 has far surpassed H1N1’s scale, but a fundamental lesson remains: going it alone is a strategy in which no one emerges victorious.

Until enough vaccines are produced, the United States will face similar challenges of equitable allocation and distribution domestically. The availability of H1N1 vaccine within the United States was beset by distribution difficulties despite extensive planning. Autopsies of H1N1 vaccination efforts demonstrate how vaccines were distributed to states without accounting for their projected need. Ill-conceived tracking systems for vaccine administration and unclear communication about multiple vaccine formulations and target groups created misperceptions.

COVID-19 vaccine distribution promises to be even more complicated given multiple encouraging candidates, which may only be efficacious in certain populations and require multiple doses. In a recent missive, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention placed responsibility on state and local health departments to identify vaccine target groups, manage vaccination plans, and track administration. This seems reasonable, but it fails to account for the decades of inexplicable, myopic funding cuts to state and local health departments.

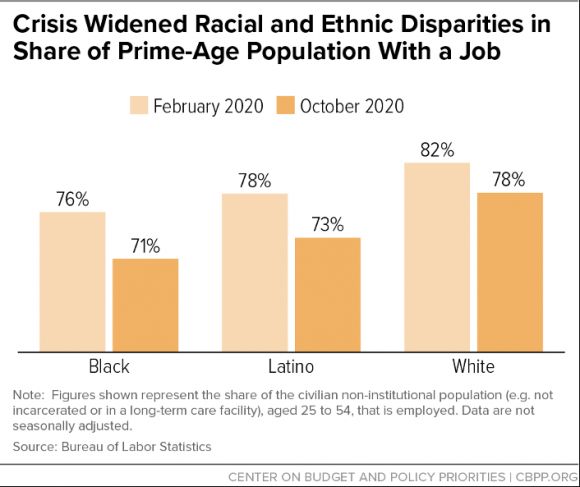

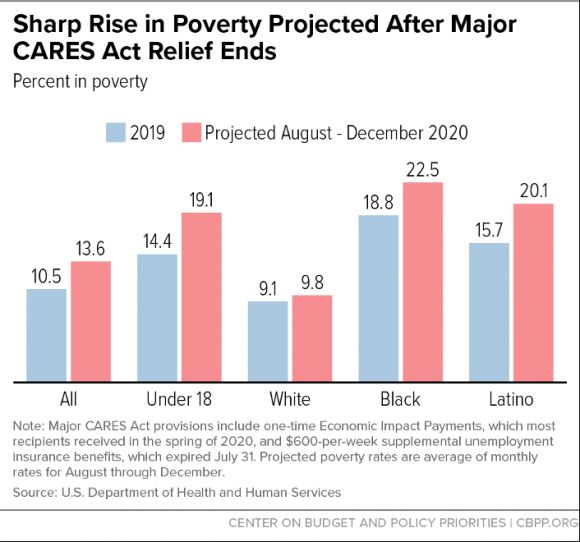

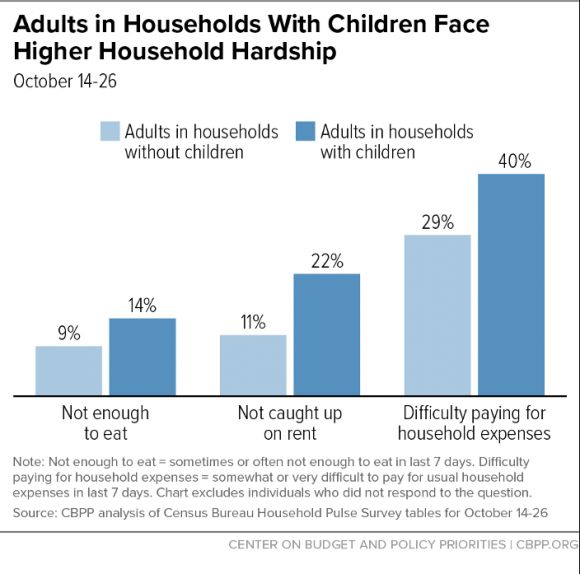

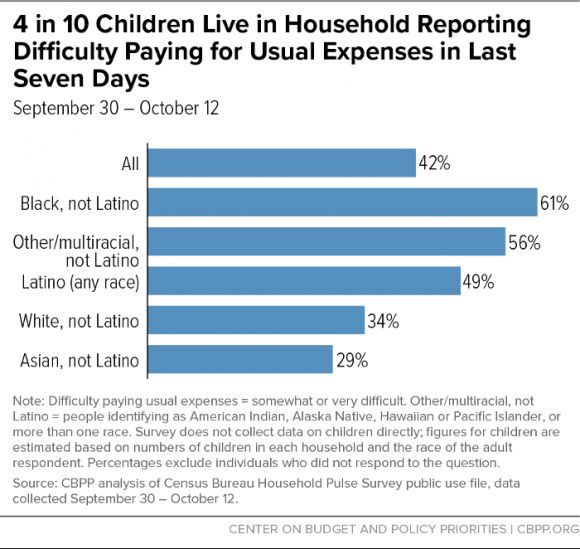

Public health departments will be hard-pressed not only to overcome existing racial and class disparities in health care access and vaccination rates but also to address inequities in infections and deaths from coronavirus due to structural racism. As with seasonal influenza vaccines, there were troubling inequities in H1N1 vaccine rates among African Americans and Hispanics, the same groups who were particularly vulnerable to infection because of poverty, chronic medical conditions, inability to socially distance, and lower health care access. Baseline disparities and underfunding of public health departments complicate efforts to avoid similar mistakes with COVID-19, which has been devastatingly concentrated among Black, Latinx, and Native American communities.

A National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine report released last month detailed a plan for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccines, and to its credit, includes an assessment of social vulnerability as an underlying principle for allocation. To the extent possible, black and brown communities, members of which constitute large proportions of essential workers unable to socially distance from home, must be prioritized for vaccine allocation.

Moreover, state Medicaid programs, which provide insurance coverage for nearly a third of the Black and a third of the Latinx nonelderly U.S. population, also face barriers to equitably delivering vaccines. Low Medicaid reimbursement rates for providers preclude their ability to vaccinate individuals fully and rapidly. During H1N1, states were left to determine their own reimbursement rates, but for COVID-19, federal support is needed to help increase providers’ ability to reach communities of color.

In so many ways, we are in unprecedented territory. But though the players have changed—a novel coronavirus, innovative vaccine technologies, newly formed international organizations—the game is in many other ways the same: constantly playing catchup, rewarding those with influence, unable to collectively share the fruits of human ingenuity. Nothing about this is immutable.

There are signs of progress, and lawmakers have taken notice. Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Jan Schakowsky proposed the COVID-19 Emergency Manufacturing Act of 2020, which seeks to establish a public system for manufacturing medicines and vaccines. If enacted, the legislation would require COVID-19 products be made available for free domestically and at cost internationally. Congresswoman Schakowsky also introduced the Make Medications Affordable by Preventing Pandemic Price-gouging Act, which prohibits monopolies on new, taxpayer-funded COVID-19 drugs and waives exclusive licenses for any drugs during a public health emergency.

The key is to extend these early steps beyond this pandemic. COVID-19 has been hailed as a once in a generation pandemic. But in this century alone we have experienced outbreaks with the potential to convert into a pandemic every few years. Old diseases spread unabated and new, more lethal viruses lie tentatively dormant. Without any changes to the underlying drivers—climate change, unchecked deforestation, increasing global travel—why should we expect that this pattern will change?

A pandemic exacerbates chronic, vexing problems, but it also sharpens our understanding of them. Crises offer rare opportunities to fundamentally change the paradigm of producing and delivering life-saving vaccines to everyone. While vaccines are far from a cure-all when it comes to fighting outbreaks, they are undeniably important. The arrival of a COVID-19 vaccine may return us to normal, but we must do better than normal—both for this pandemic and the inevitable next one.

Decades-long funding cuts for pandemic preparedness hamper coordinated distribution and equitable access. We must reimagine how to make life-saving vaccines available to everyone.

November 14, 2020 Ravi Gupta BOSTON REVIE

Nearly a year into a pandemic that has killed more than a million people and laid waste to both public health systems and the global economy, many have turned their hopes to a vaccine. Optimism has been buoyed by the historic pace of development of multiple COVID-19 vaccine candidates and the recent news that Pfizer, in partnership with the small company BioNTech, has reported preliminary data on a vaccine candidate showing 90 percent effectiveness. The arrival of a vaccine in the next few months would be a remarkable feat, but fundamental questions—beyond basic assurances of safety and efficacy—remain. Will there be enough doses, and who will get them?

This is not the first time we face questions of equitably deploying a vaccine during an outbreak. Eleven years ago, as the H1N1 virus swept across the United States and 73 other countries, the World Health Organization declared the first pandemic in over forty years. H1N1 seemed deadlier and more transmissible than seasonal influenza. Recollections of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic’s colossal death toll occupied the collective psyche. An H1N1 vaccine seemed essential to prevent history from repeating, much as a COVID-19 vaccine does now.

Development of an H1N1 vaccine progressed rapidly, in large part due to existing technology and regulatory systems for seasonal influenza vaccines. But avoiding preventable deaths required ensuring the vaccine’s prompt manufacturing and equitable distribution within the U.S. and across the world. Manufacturing delays led to shortages that complicated an already halting domestic distribution plan, and by the time the vaccine supply increased, the pandemic had waned. All told, 90 of 162 million doses were utilized in the United States. The rest were donated to other countries (after broken pledges to do so earlier) or simply thrown away. A truth was illuminated that persists today: the prevailing system of vaccine production and distribution is not designed to promote equitable access.

Much has changed since the H1N1 pandemic. Technological platforms have advanced considerably. International institutions have forged partnerships to prioritize therapeutic and vaccine candidates. Financing of vaccine development has evolved, with the creation of non-profit entities like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).

Yet much remains the same. Vaccine manufacturing remains unprepared for surges and without a global entity charged with centralized financing. International legal agreements ensuring equitable access are non-enforceable. The international hoarding and price gouging for personal protective equipment early in this pandemic are harbingers for vaccine maldistribution to the highest bidder. Within the United States, in particular, decades-long funding cuts for pandemic preparedness and public health hamper coordinated distribution for efficient access. Surviving a pandemic requires extraordinary movement on these issues. We must reimagine how to make life-saving vaccines available to everyone, for pathogens both new and old.

Deployment of H1N1 vaccines faced a bottleneck that we still face today: insufficient manufacturing capacity. Coordination between manufacturers, government agencies, and universities in multiple continents led to the FDA approval of four H1N1 vaccines within six months. But enough vaccine could simply not be produced in time. Years of industry consolidation due to limited profits from vaccine development had left just three companies available to manufacture the majority of global influenza vaccines. Manufacturing capacity was dependent on well-established but time-consuming and unpredictable egg-based technology from World War II, while production lines were already occupied with seasonal flu vaccines.

Today, the leading COVID-19 vaccine candidates rely on novel technology that hasn’t yet been deployed at scale. These platforms have the potential for faster production, but they will likely face unforeseen difficulties. Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, for example—like Pfizer and BioNTech’s—require temperatures as low as -94 degrees Fahrenheit to maintain stability, whereas H1N1 vaccines were easily stored in small fridges. COVID-19 vaccines will likely require two doses, doubling the total number needed, while H1N1 vaccines required just one.

At the root of the manufacturing problem is a near exclusive reliance on the private sector, which has limited incentives for preemptive investment. As a result, funding hastily flows from public coffers to private companies to bolster manufacturing capacity once an outbreak has already begun. During the H1N1 pandemic, the U.S. government awarded contracts to manufacturers to upgrade their facilities and start vaccine production. With COVID-19, we’ve seen a dizzying number of agreements between governments and private companies to scale production, among them agreements facilitated by the U.S. public-private partnership Operation Warp Speed.

Of course, it isn’t feasible to expect immediate global availability of sixteen billion doses. But a reactive approach to vaccine production grounded in a market-based logic de-emphasizes the long-term readiness and preparation needed for efficient and equitable deployment of a vaccine in a pandemic.

We need an alternative approach that centers on maintaining public manufacturing facilities to respond to the acute needs of an outbreak before it happens. In the wake of H1N1, the U.S. government invested in developing four manufacturing sites in concert with a university and private companies. But these facilities lacked sustained development and were unequipped for rapid, mass production during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the past few months, substantial Operation Warp Speed funds have gone to the Texas A&M University System and Emergent Solutions to partner with vaccine developers to manufacture doses. It remains to be seen whether an injection of funds at this moment will help construct and maintain a sustainable, public manufacturing sector for future outbreaks. We should recognize that preparedness is not a novel concept; epidemiologists and national security experts alike have been arguing about its importance for decades. Twenty years ago, science journalist Laurie Garrett characterized the collapse of global health infrastructure as a “betrayal of trust.” We are witnessing the effects of that betrayal today.

An initial vaccine shortfall necessitates thoughtful distribution to enable equitable global access. The H1N1 pandemic exposed glaring disparities between rich and poor nations in procuring vaccines. Before a pandemic was even declared, developed countries placed large advance orders with manufacturers. The World Health Organization secured small donation commitments from developed countries and manufacturers for developing countries. The United States pledged to donate 10 percent of its vaccines, but as H1N1 cases and vaccine shortages increased, it rescinded its offer. Canada and Australia permitted exports from their domestic manufacturers only after their own citizens were immunized. Eventually, 78 million doses—an inadequate amount to begin with—were donated to 77 countries, but the worst of the pandemic had already passed.

Fears of such vaccine nationalism—countries prioritizing their own populations at the expense of a globally coordinated strategy—have materialized in the current pandemic, too. Multilateral advance market commitments, a form of payment to manufacturers predicated on proof of a successful vaccine, are meant to equitably allocate vaccines among countries. Various advance market commitments (AMCs) have been proposed and created for COVID-19 vaccines, including $2 billion in urgent funding specifically for low- and middle-income country AMCs as part of an effort by the COVAX facility—an international collaboration between the World Health Organization, CEPI, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance—to deliver 2 billion doses globally by the end of 2021. (COVAX estimates the total cost for delivering on its plan to be $18.1 billion.)

Though advance market commitments such as the Gavi-led pneumococcal vaccine fund have been used successfully (though not without criticism of its price and lack of transparency), COVID-19 is the first test of whether they can function during a pandemic affecting wealthy and poor countries simultaneously. Bilateral agreements between manufacturers and individual wealthy countries who seek to guarantee their own supply have undermined the COVAX advance market commitment and precluded efficient and equitable global allocation of potential vaccines. Pfizer and BioNTech, for instance, have yet to sign any agreements to provide developing countries with their vaccine, and the majority of their initial supply has already been claimed by wealthier countries.

An enforceable trade and investment agreement is needed. Sadly, simply beginning these discussions seems too advanced when the Trump administration has amazingly sought to withdraw funding and support from the World Health Organization and refused to join COVAX—even though more than 150 countries have joined.

The absence of a global strategy encompassing high-risk populations is morally reprehensible, but it also makes no biological or economic sense. The virus will continue to spread without coordination for vaccine allocation based on need. Elements of international integration and global travel that accelerated this pandemic will perpetuate transmission. Global trade and tourism will further suffer. COVID-19 has far surpassed H1N1’s scale, but a fundamental lesson remains: going it alone is a strategy in which no one emerges victorious.

Until enough vaccines are produced, the United States will face similar challenges of equitable allocation and distribution domestically. The availability of H1N1 vaccine within the United States was beset by distribution difficulties despite extensive planning. Autopsies of H1N1 vaccination efforts demonstrate how vaccines were distributed to states without accounting for their projected need. Ill-conceived tracking systems for vaccine administration and unclear communication about multiple vaccine formulations and target groups created misperceptions.

COVID-19 vaccine distribution promises to be even more complicated given multiple encouraging candidates, which may only be efficacious in certain populations and require multiple doses. In a recent missive, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention placed responsibility on state and local health departments to identify vaccine target groups, manage vaccination plans, and track administration. This seems reasonable, but it fails to account for the decades of inexplicable, myopic funding cuts to state and local health departments.

Public health departments will be hard-pressed not only to overcome existing racial and class disparities in health care access and vaccination rates but also to address inequities in infections and deaths from coronavirus due to structural racism. As with seasonal influenza vaccines, there were troubling inequities in H1N1 vaccine rates among African Americans and Hispanics, the same groups who were particularly vulnerable to infection because of poverty, chronic medical conditions, inability to socially distance, and lower health care access. Baseline disparities and underfunding of public health departments complicate efforts to avoid similar mistakes with COVID-19, which has been devastatingly concentrated among Black, Latinx, and Native American communities.

A National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine report released last month detailed a plan for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccines, and to its credit, includes an assessment of social vulnerability as an underlying principle for allocation. To the extent possible, black and brown communities, members of which constitute large proportions of essential workers unable to socially distance from home, must be prioritized for vaccine allocation.

Moreover, state Medicaid programs, which provide insurance coverage for nearly a third of the Black and a third of the Latinx nonelderly U.S. population, also face barriers to equitably delivering vaccines. Low Medicaid reimbursement rates for providers preclude their ability to vaccinate individuals fully and rapidly. During H1N1, states were left to determine their own reimbursement rates, but for COVID-19, federal support is needed to help increase providers’ ability to reach communities of color.

In so many ways, we are in unprecedented territory. But though the players have changed—a novel coronavirus, innovative vaccine technologies, newly formed international organizations—the game is in many other ways the same: constantly playing catchup, rewarding those with influence, unable to collectively share the fruits of human ingenuity. Nothing about this is immutable.

There are signs of progress, and lawmakers have taken notice. Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Jan Schakowsky proposed the COVID-19 Emergency Manufacturing Act of 2020, which seeks to establish a public system for manufacturing medicines and vaccines. If enacted, the legislation would require COVID-19 products be made available for free domestically and at cost internationally. Congresswoman Schakowsky also introduced the Make Medications Affordable by Preventing Pandemic Price-gouging Act, which prohibits monopolies on new, taxpayer-funded COVID-19 drugs and waives exclusive licenses for any drugs during a public health emergency.

The key is to extend these early steps beyond this pandemic. COVID-19 has been hailed as a once in a generation pandemic. But in this century alone we have experienced outbreaks with the potential to convert into a pandemic every few years. Old diseases spread unabated and new, more lethal viruses lie tentatively dormant. Without any changes to the underlying drivers—climate change, unchecked deforestation, increasing global travel—why should we expect that this pattern will change?

A pandemic exacerbates chronic, vexing problems, but it also sharpens our understanding of them. Crises offer rare opportunities to fundamentally change the paradigm of producing and delivering life-saving vaccines to everyone. While vaccines are far from a cure-all when it comes to fighting outbreaks, they are undeniably important. The arrival of a COVID-19 vaccine may return us to normal, but we must do better than normal—both for this pandemic and the inevitable next one.