Before the world knew what intersectionality was, the scholar, writer and activist was living it, arguing not just for Black liberation, but for the rights of women and queer and transgender people as well.

October 22, 2020

Nelson George; Photographs by John Edmonds NEW YORK TIMES

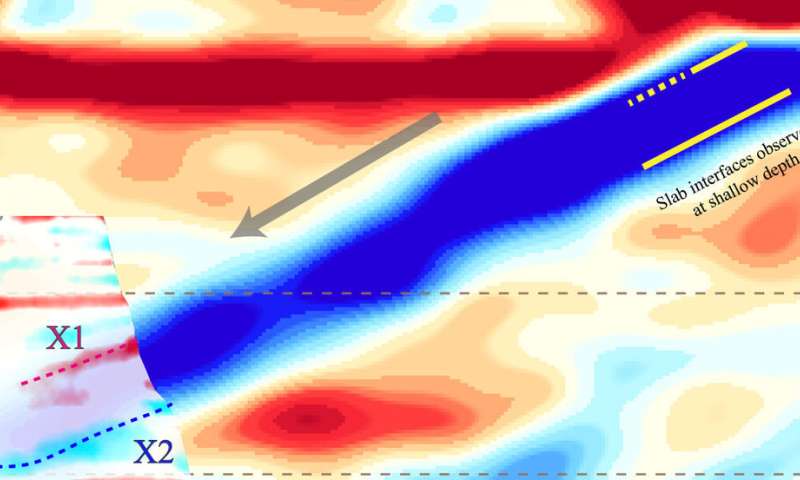

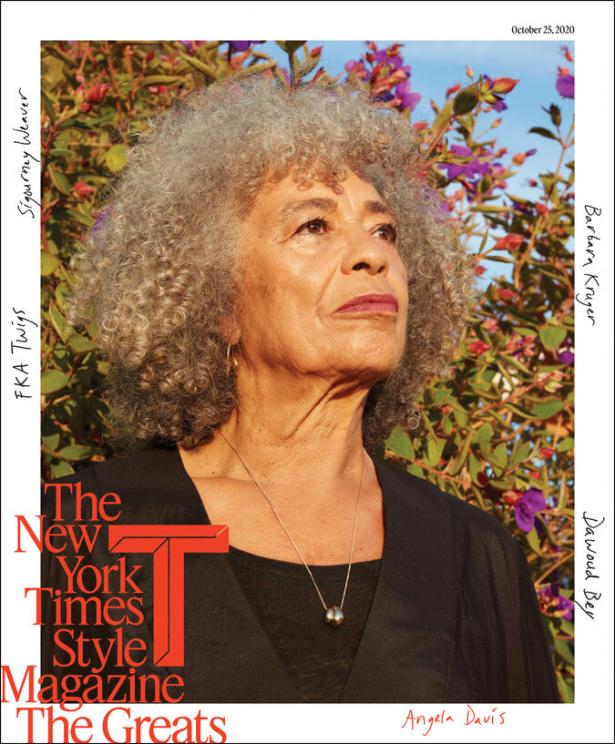

Angela Davis, Photograph by John Edmonds // New York Times

THERE’S A WALL on Throop Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, that is painted with a mural of Black icons. It begins with Bob Marley and Haile Selassie before going on to include Martin Luther King Jr., Betty Shabazz (Betty X) and Nelson Mandela. The last portrait is of Angela Yvonne Davis — scholar, activist and the only surviving hero of the global African diaspora. Davis’s image is painted from a photograph taken in the early ’70s, when she became a symbol of the struggle for Black liberation, anticapitalism and feminism. It’s a powerful portrait — she is wearing her hair in a round, black Afro, her hand curled as if she’s making a rhetorical point. Her expression is pensive, intelligent, challenging.

For the mural’s context, we have to return to the fall of 1969, when Davis, then an assistant professor in the philosophy department at the University of California, Los Angeles, was fired at the beginning of the school year for her membership in the Communist Party, and then, after a court ruled the termination illegal, fired again nine months later for using “inflammatory rhetoric” in public speeches. She had recently become close to a trio of Black inmates nicknamed the Soledad Brothers (after the California prison in which they were held) who had been charged with the murder of a white prison guard in January 1970. One, George Jackson, was an activist and writer whom Davis befriended upon joining a committee challenging the charges. In August 1970 — after Jackson’s younger brother, Jonathan, used firearms registered to Davis in a takeover of a Marin County courthouse that left four people dead — Davis immediately came under suspicion. In the aftermath of that bloody event, she was charged with three capital offenses, including murder.

Angela Davis included in a mural in Brooklyn, N.Y., along with Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

Nicholas Calcott // New York Times

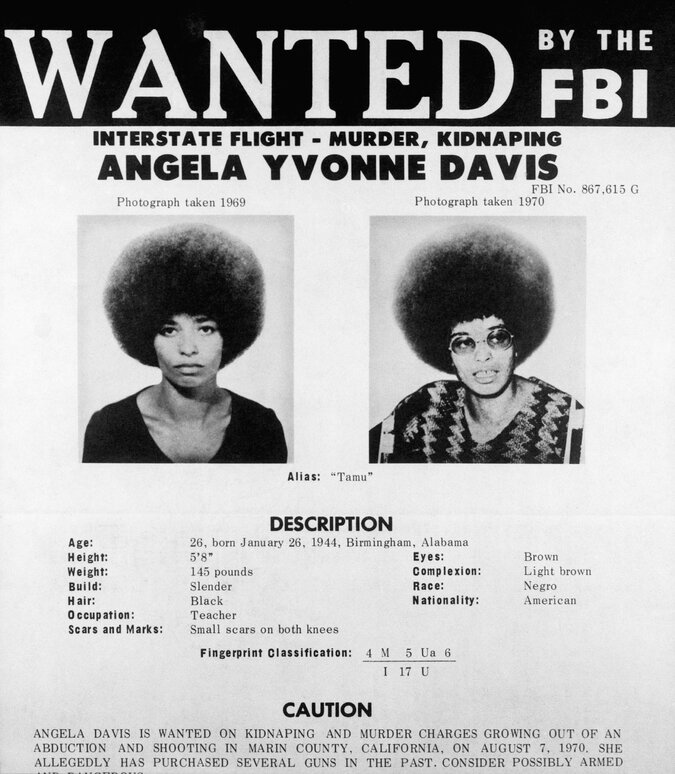

Overnight, she became an outlaw. Within two weeks of the shootout, J. Edgar Hoover placed Davis on the F.B.I.’s Ten Most Wanted list, making her the third woman ever to be included. A national manhunt ensued before she was detained two months later in a New York motel. President Nixon congratulated the bureau on capturing “the dangerous terrorist Angela Davis.” After her arrest, the chant “Free Angela!” became a global battle cry as the academic — who had studied philosophy in East and West Germany in the late ’60s and had been a vocal supporter of the Black Panthers and the anti-Vietnam War movement — became widely viewed on the left as a political prisoner. She spent 18 months in jail before being found not guilty on all charges.

During the trial, Davis’s profile transformed. Before, she had been a noted scholar. After, she became an international symbol of resistance. In a period when images of Black women in major newspapers or on network television were scarce, Davis’s was both ubiquitous and unique. Whether in journalistic photos, respectful drawings or disrespectful caricatures, her gaze was uniformly stern — as if focused on her offscreen accusers — and unbowed. No matter the platform or the publication, she radiated rebellion and intelligence. When I search her name online today, there are countless images from this period to scroll through. There’s a drawing of a bespectacled Davis that reads, “You can jail a revolutionary, but you can’t jail a revolution.” There’s a photo of her holding a microphone at a rally, her own words written beneath: “The real criminals in this society are not all of the people who populate the prisons across the state, but those who have stolen the wealth of the world from the people.” There’s a painting of her washed with the red, black and green of the Pan-African flag. There’s a poster that makes her look like a sexy saint, with the words “Free Angela” hanging above and below her face; an Ecuadorean pennant depicting Davis in shackles alongside a sickle and hammer and the phrase “Libertad Para Angela Davis” — and hundreds and hundreds more.

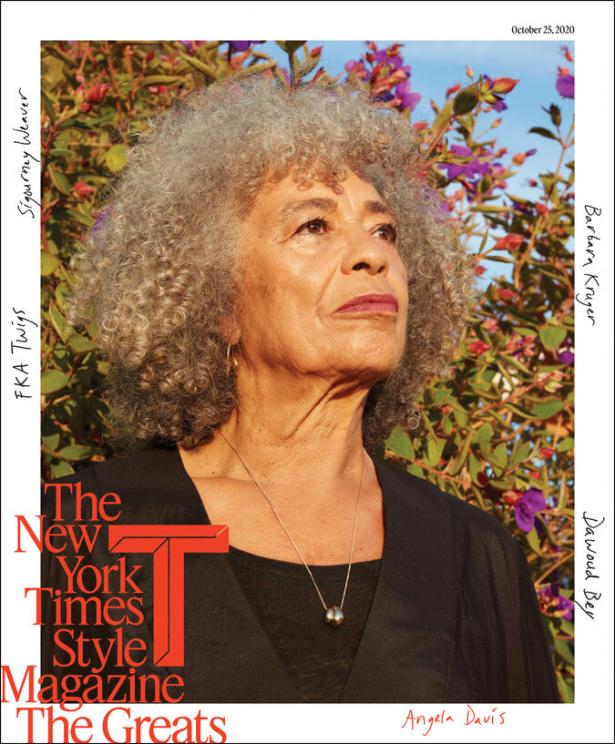

Angela Davis on the FBI’s list of “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives,” August 1970.

Bettmann/Getty Images // New York Times

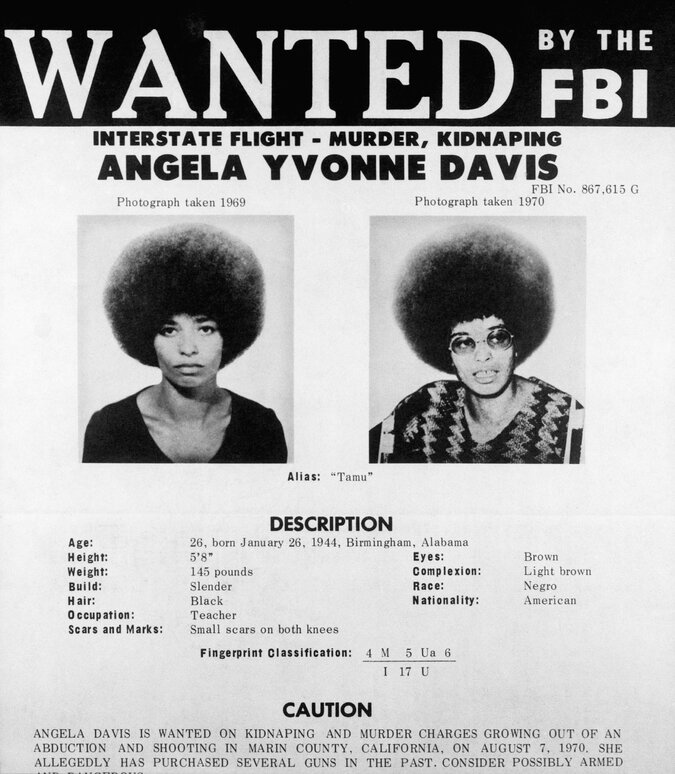

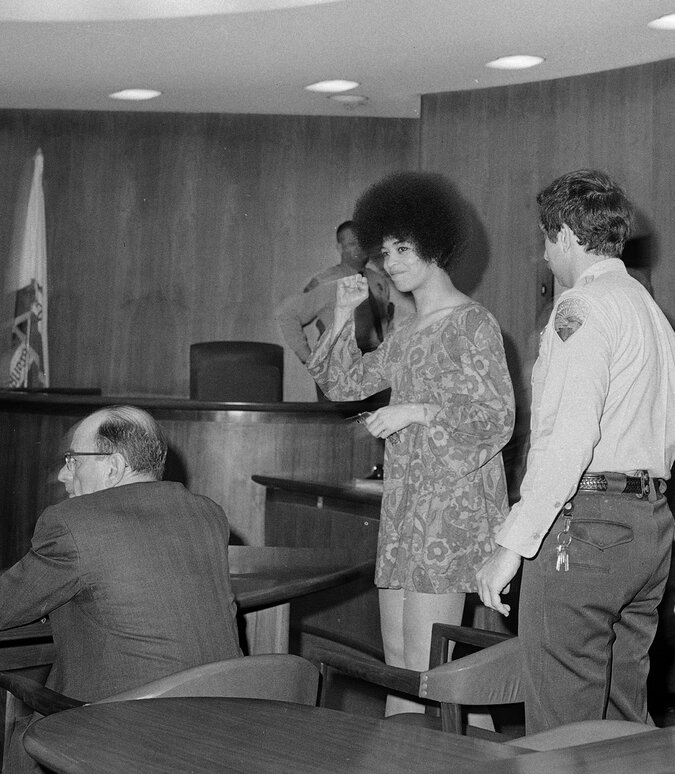

Davis gives the Black Power salute as she enters court in San Rafael, Calif., following her extradition from New York, Dec. 23, 1970. (John Abt, one of the early defense lawyers is seated on her left.)

Associated Press // New York Times

The consistent theme is a woman both radical and chic. Davis was more likely to be seen than read or heard at the time, but her very existence complicated the white and Black male gaze of what Black women could be. The impact of this representation has lingered in the culture. Consider this: For 50 years, Davis has existed as a pop-cultural reference point as well as a serious academic, one whose ideas were once thought of as extreme but are now part of the popular discourse. Both the Rolling Stones as well as John Lennon and Yoko Ono recorded songs about her in the early ’70s (“Sweet Black Angel” and “Angela,” respectively). In 1977, the great Vonetta McGee portrayed a watered-down version of Davis in the little-seen prison drama “Brothers,” based on her relationship with Jackson. Davis’s niece, Eisa, wrote and performed a critically acclaimed autobiographical play, “Angela’s Mixtape,” in 2009 about having a radical star as her aunt. A long-lost jailhouse interview with Davis was the highlight of the 2011 documentary “The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975,” and a year later, the director Shola Lynch’s “Free Angela and All Political Prisoners,” which was executive produced by Jay-Z, Will Smith, Jada Pinkett Smith and James Lassiter, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. All of these projects have celebrated, even fetishized, that brief, electric period in Davis’s life.

Angela Davis, Photograph by John Edmonds // New York Times

THERE’S A WALL on Throop Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, that is painted with a mural of Black icons. It begins with Bob Marley and Haile Selassie before going on to include Martin Luther King Jr., Betty Shabazz (Betty X) and Nelson Mandela. The last portrait is of Angela Yvonne Davis — scholar, activist and the only surviving hero of the global African diaspora. Davis’s image is painted from a photograph taken in the early ’70s, when she became a symbol of the struggle for Black liberation, anticapitalism and feminism. It’s a powerful portrait — she is wearing her hair in a round, black Afro, her hand curled as if she’s making a rhetorical point. Her expression is pensive, intelligent, challenging.

For the mural’s context, we have to return to the fall of 1969, when Davis, then an assistant professor in the philosophy department at the University of California, Los Angeles, was fired at the beginning of the school year for her membership in the Communist Party, and then, after a court ruled the termination illegal, fired again nine months later for using “inflammatory rhetoric” in public speeches. She had recently become close to a trio of Black inmates nicknamed the Soledad Brothers (after the California prison in which they were held) who had been charged with the murder of a white prison guard in January 1970. One, George Jackson, was an activist and writer whom Davis befriended upon joining a committee challenging the charges. In August 1970 — after Jackson’s younger brother, Jonathan, used firearms registered to Davis in a takeover of a Marin County courthouse that left four people dead — Davis immediately came under suspicion. In the aftermath of that bloody event, she was charged with three capital offenses, including murder.

Angela Davis included in a mural in Brooklyn, N.Y., along with Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

Nicholas Calcott // New York Times

Overnight, she became an outlaw. Within two weeks of the shootout, J. Edgar Hoover placed Davis on the F.B.I.’s Ten Most Wanted list, making her the third woman ever to be included. A national manhunt ensued before she was detained two months later in a New York motel. President Nixon congratulated the bureau on capturing “the dangerous terrorist Angela Davis.” After her arrest, the chant “Free Angela!” became a global battle cry as the academic — who had studied philosophy in East and West Germany in the late ’60s and had been a vocal supporter of the Black Panthers and the anti-Vietnam War movement — became widely viewed on the left as a political prisoner. She spent 18 months in jail before being found not guilty on all charges.

During the trial, Davis’s profile transformed. Before, she had been a noted scholar. After, she became an international symbol of resistance. In a period when images of Black women in major newspapers or on network television were scarce, Davis’s was both ubiquitous and unique. Whether in journalistic photos, respectful drawings or disrespectful caricatures, her gaze was uniformly stern — as if focused on her offscreen accusers — and unbowed. No matter the platform or the publication, she radiated rebellion and intelligence. When I search her name online today, there are countless images from this period to scroll through. There’s a drawing of a bespectacled Davis that reads, “You can jail a revolutionary, but you can’t jail a revolution.” There’s a photo of her holding a microphone at a rally, her own words written beneath: “The real criminals in this society are not all of the people who populate the prisons across the state, but those who have stolen the wealth of the world from the people.” There’s a painting of her washed with the red, black and green of the Pan-African flag. There’s a poster that makes her look like a sexy saint, with the words “Free Angela” hanging above and below her face; an Ecuadorean pennant depicting Davis in shackles alongside a sickle and hammer and the phrase “Libertad Para Angela Davis” — and hundreds and hundreds more.

Angela Davis on the FBI’s list of “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives,” August 1970.

Bettmann/Getty Images // New York Times

Davis gives the Black Power salute as she enters court in San Rafael, Calif., following her extradition from New York, Dec. 23, 1970. (John Abt, one of the early defense lawyers is seated on her left.)

Associated Press // New York Times

The consistent theme is a woman both radical and chic. Davis was more likely to be seen than read or heard at the time, but her very existence complicated the white and Black male gaze of what Black women could be. The impact of this representation has lingered in the culture. Consider this: For 50 years, Davis has existed as a pop-cultural reference point as well as a serious academic, one whose ideas were once thought of as extreme but are now part of the popular discourse. Both the Rolling Stones as well as John Lennon and Yoko Ono recorded songs about her in the early ’70s (“Sweet Black Angel” and “Angela,” respectively). In 1977, the great Vonetta McGee portrayed a watered-down version of Davis in the little-seen prison drama “Brothers,” based on her relationship with Jackson. Davis’s niece, Eisa, wrote and performed a critically acclaimed autobiographical play, “Angela’s Mixtape,” in 2009 about having a radical star as her aunt. A long-lost jailhouse interview with Davis was the highlight of the 2011 documentary “The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975,” and a year later, the director Shola Lynch’s “Free Angela and All Political Prisoners,” which was executive produced by Jay-Z, Will Smith, Jada Pinkett Smith and James Lassiter, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. All of these projects have celebrated, even fetishized, that brief, electric period in Davis’s life.

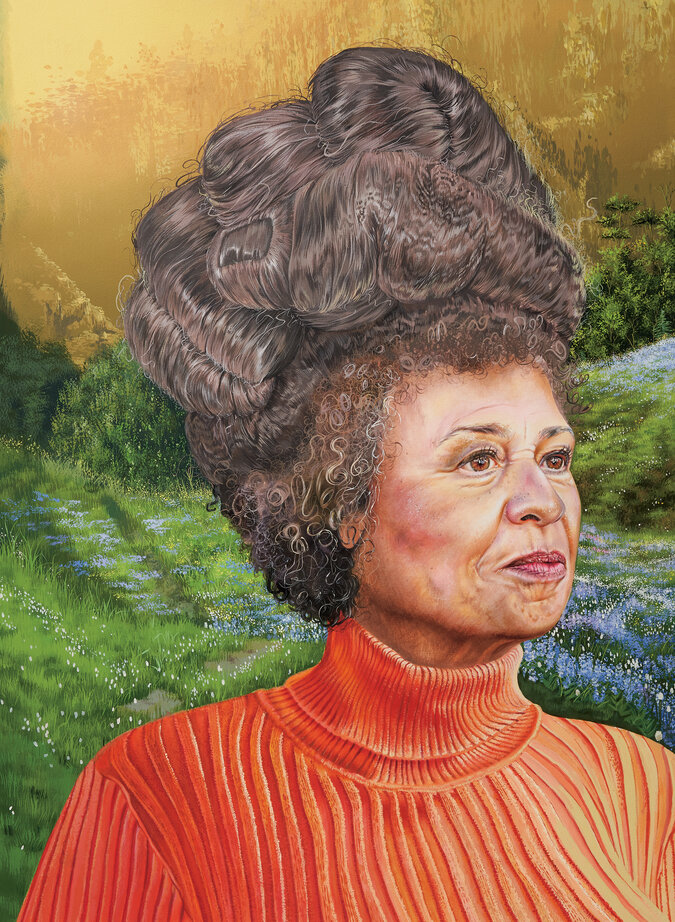

In the ’70s, before the world fully understood who Davis was, they knew her face. She became, in a way very few public intellectuals ever do, an icon, a powerful image of Black femalehood in a culture that often reduced Black women to stereotypes. It’s in celebration of Davis’s ongoing visual impact and presence that T Magazine asked three young Black American artists to create portraits of Davis for this issue. “When I was in high school, I had an Afro,” says the Fresno, Calif.-based artist Kezia Harrell, 27, of the influence Davis — who has worn her own hair in an Afro since the late ’60s — has had on her life. “I had the world on top of my head.” Harrell painted Davis in an orange sweater she wore in 1972, and “imagined her gazing at freedom — a theme of such far distance.”

Kezia Harrell’s “Angela As Black Divinity” (2020).

Photograph by Weichia Huang // New York Times

BUT DAVIS, now 76, is not just an image on a wall or a talking head in a documentary. She remains a vital presence in the world, lecturing at major universities and advising young activists, like the Dream Defenders, a group founded in 2012 after the killing of Trayvon Martin. For most of the last 30 years, she has worked as a public intellectual, teaching at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and other universities, and embodying the kind of left-wing professor who drives conservatives crazy. She spoke out against the war on terror after 9/11, blamed the devastation in New Orleans caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 on structural racism and spoke at Occupy Wall Street rallies in Philadelphia and New York in 2011. In 2018, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Alabama invited her to receive an award, which was rescinded three months later after unnamed members of the community complained to the board about her support for Palestinian rights and a boycott of Israel. (The institute eventually reversed its decision and issued Davis a public apology.) Because of her personal history, ongoing engagement and career as a scholar, Davis is in a distinct position to connect the radical traditions of the ’60s to Trump-era activism.

Yet Davis is distinct in another way as well. Over the years, I’ve come in contact with a great many people who were activists during the Black Power era. Some are nested in academia. Quite a few have retired to the South. What unites them are the scars they carry: from being persecuted by the police and F.B.I., from being challenged on their more radical views by integrationist parents and friends, from the profound sadness they share over the fact that the revolution they fought for has yet to materialize. Davis is their peer, but she has shrugged off defeat — she still believes that America can be transformed into a more equitable society. She has kept her fire while relishing what she can learn from younger generations. Hers is a kind of openness and generosity that makes her not just an elder but a still-active participant in change.

Photograph by Weichia Huang // New York Times

BUT DAVIS, now 76, is not just an image on a wall or a talking head in a documentary. She remains a vital presence in the world, lecturing at major universities and advising young activists, like the Dream Defenders, a group founded in 2012 after the killing of Trayvon Martin. For most of the last 30 years, she has worked as a public intellectual, teaching at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and other universities, and embodying the kind of left-wing professor who drives conservatives crazy. She spoke out against the war on terror after 9/11, blamed the devastation in New Orleans caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 on structural racism and spoke at Occupy Wall Street rallies in Philadelphia and New York in 2011. In 2018, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Alabama invited her to receive an award, which was rescinded three months later after unnamed members of the community complained to the board about her support for Palestinian rights and a boycott of Israel. (The institute eventually reversed its decision and issued Davis a public apology.) Because of her personal history, ongoing engagement and career as a scholar, Davis is in a distinct position to connect the radical traditions of the ’60s to Trump-era activism.

Yet Davis is distinct in another way as well. Over the years, I’ve come in contact with a great many people who were activists during the Black Power era. Some are nested in academia. Quite a few have retired to the South. What unites them are the scars they carry: from being persecuted by the police and F.B.I., from being challenged on their more radical views by integrationist parents and friends, from the profound sadness they share over the fact that the revolution they fought for has yet to materialize. Davis is their peer, but she has shrugged off defeat — she still believes that America can be transformed into a more equitable society. She has kept her fire while relishing what she can learn from younger generations. Hers is a kind of openness and generosity that makes her not just an elder but a still-active participant in change.

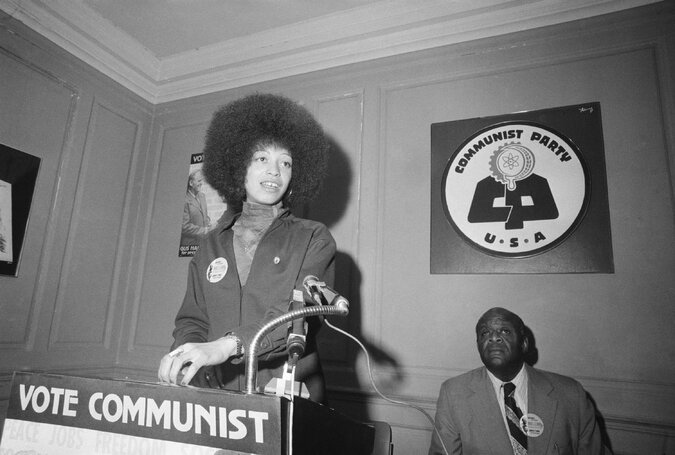

Davis speaking at a press conference in 1976 at the Communist Party U.S.A.’s National Party Headquarters, in New York City. She was the Party’s nomination for vice president in 1980 and 1984. (Seated is Henry Winston, then National Chairman of the CPUSA.)

Bettmann/Getty Images // New York Times

Icons of the nonviolent civil rights movement — people such as the late congressman John Lewis — are rightfully revered for their sacrifices in the face of violent white resistance to integration. But, as former President Bill Clinton’s dismissive reference to Kwame Ture (née Stokely Carmichael, who ousted Lewis as head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1966 by advocating for Black political autonomy) at Lewis’s funeral earlier this year suggests, there’s no love lost between mainstream liberalism and the more so-called radical voices that arose in the ’70s. There are no monuments for the many who died in targeted police shootings or annual tributes to the people incarcerated because of the F.B.I.’s counterintelligence program (Cointelpro), partly aimed at destroying more aggressive Black agitation. There are no statues or memorials in Oakland, Calif., honoring the Black Panthers (though there are quite a few murals). Angela Davis survived that dangerous time with her reputation intact, her spirit unbroken and her critical vision of the American free-enterprise system unchanged. She may not be a very comfortable connection to America’s period of “We Shall Overcome,” but she is to a piercing and radical tradition of struggle in the Black community that has never, as the kids say, “been given their flowers.” As a bridge between the past and present eras of protest, Davis can explain both what went right and wrong while also helping to shape the future. Her face may be on a mural, but it is also out in the world.

TODAY, DAVIS’S HAIR is gray, though it still circles her head like a crown. From the garden of her modest eucalyptus-tree-shaded second home in Mendocino, Calif., she expresses a relaxed optimism about the country’s direction. As befits a professor who has taught history of consciousness, critical theory and feminist studies for five decades, her speech is peppered with references to scholars and activists such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Stuart Hall, historical figures such as Prudence Crandall (a white Quaker who opened a school for Black girls in Connecticut in 1833) and the white writer and civil rights activist Anne Braden, whom she considers a mentor. In on-camera interviews from the ’70s, Davis’s voice is melodic yet tart, with a clipped precision she used to scold naïve and hostile reporters. Decades later, the melody is still there, but it’s now manifested in a smooth, almost instructional flow, the result of years of delivering lectures.

“The orange in her hands is illumination,” says the New Haven, Conn.-based artist Tschabalala Self, 30, of her portrait. “It speaks to passing on a message that has something of value, an aura.” Self, who wanted Davis to look regal and powerful, imagined the activist orating to young Black people, referencing silhouettes from the time she came to prominence in the 1970s.

Tschabalala Self’s “Angela” (2020).

Photograph by Weichia Huang // New York Times

Davis — who has written or edited nine books and retired from teaching at U.C. Santa Cruz in 2008 — is still very much defined by the iconography of her past. It hasn’t always been easy. “For a long time, I felt somewhat intimidated,” she acknowledges. “I felt that there was no way that I, as an individual, could actually live up to the expectations incorporated in that image. There came a point when I realized I didn’t have to. The image does not reflect who I am as an individual, it reflects the work of the movement.”

The turning point occurred a few years ago, when she met a young woman in a foster-care program who was visiting U.C. Santa Cruz. “She had on a T-shirt with my image on it,” Davis recalls. “My usual stance had been, whenever I would see people wearing T-shirts with my image, I didn’t really know how to act. I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know how to respond. But this time, I asked her, ‘Why are you wearing that T-shirt? What does that image mean to you?’ She didn’t know a great deal about me at all, but she said, ‘Whenever I wear this, I feel like I can accomplish anything. It makes me feel empowered.’ From that moment, I realized it really was not about me as an individual. It was about the fact that my image was a stand-in for the work that masses are able to do in terms of changing the world.”

IN 1974, JOAN LITTLE, a 20-year-old Black inmate in a North Carolina jail, killed her rapist, the corrections officer Clarence Alligood, and pleaded self-defense after being indicted on a charge of murder. Davis wrote a piece on the case for Ms. magazine, which had been launched three years earlier, that focused on the underreported history of white male rape of Black women as a tool of social control. Later, she became an adviser to the defense. The underlying assumption of the prosecution (and of many white Southerners) was that a white man couldn’t rape a Black woman, that she had to have seduced her jailer, and that the case was open-and-shut. Little’s trial united the civil rights, the feminist and the jail-reform movements in what was then an unusual confluence of progressive forces. In a stunning victory, Little was found not guilty of murder — a ruling that, at the time, astonished both Black and white residents in the still de facto segregated South and sounds almost like science fiction to folks raised in the current era, when law enforcement misconduct is rarely punished and Black victims are rarely believed.

Davis published “Women, Race & Class” in 1981, inspired both by her time in jail and Little’s case, as well as by her work championing the cases of other unfairly incarcerated Black women and men. “That book represents a number of positions of people who had a broader, more — the term we use now is ‘intersectional’ — analysis of what it means to struggle for gender equality,” she says. “At the time that I wrote it, I was interested in pointing out that gender did not have to be seen in competition with race. That women’s issues did not belong to middle-class white women. In many ways, that research was about uncovering the contributions of women who were completely marginalized by histories of the women’s movement, especially Black women, but also Latino women and working-class women.”

For many contemporary African-American activists, race has been a blind spot for white feminists and for the feminist movement at large. The second-wave feminism of the ’70s was — much like its forerunner, the suffrage movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries — driven by white women seeking equality with men in terms of opportunity, legal protections and control of their bodies. But the numerous issues of inequality facing working-class and poor Black women — in addition to destroying the cartoonish sexualization of Black men as threats to white women — had never been very vital to the mainstream feminist agenda. These are problems Davis identified when she was trying to grow support for Delbert Tibbs, a Black man falsely accused of rape and murder in Florida in the mid-70s. “He was facing the death penalty,” she recalls. “We were appealing to these white feminists to support him as well as Little, and there was reluctance. Some white feminists did, but by and large that appeal fell flat. So how is it possible to develop the kinds of arguments that will allow people to recognize that one cannot effectively struggle for gender equality without racial equality?” Although she’s an essential figure in modern feminism, Davis remains a sympathetic skeptic of much feminist orthodoxy. She believes narrow definitions of any progressive movement feed a self-centeredness that limits its ability to unify with other groups. In other words, she understood the necessity of intersectionality before the term was even invented.

Davis has kept her fire while relishing what she can learn from younger generations.

“Intersectionality” is a neologism introduced in 1989 by the Black law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, who teaches at U.C.L.A. and Columbia University. The concept invites us to see various forms of inequality as a prism. Its original organizing principle — that Black women are subject to discrimination based not just on race, class or sex but the interaction of all of them — has since been applied to other groups and animates much of today’s progressive political conversations and activity. Yet as Davis knows from her work in the ’70s, asking various advocacy groups to embrace this philosophy is easier to demand from a podium than to write into policy, where efforts have been stymied by self-interest and personal prejudices. But as we discuss her past, I detect no cynicism, no despair nor frustration — this despite decades of glacial progress and the current White House occupant’s vision of America as white nirvana. In America’s deepening income inequality, Davis sees a chance for us to re-examine capitalism, which she views as irredeemably flawed. Her optimism is particularly remarkable when you consider how long she’s believed that America could change. No, her generation did not get their revolution. And yet in so much of what they did accomplish — with civil rights, women’s rights, L.G.B.T.Q. rights, the environment and scores of other issues — they have radically shifted America’s expectations and norms.

Along with coalition building, Davis has long been passionate about radically changing the criminal justice system. While defunding the police has become a philosophical touchstone for Black Lives Matter and other activists, a reimagining of policing and incarceration has been essential to her vision for decades. In 1997, she was one of the founders of Critical Resistance, an organization dedicated to abolishing the prison system. In “Are Prisons Obsolete?” (2003), she argued that “the most difficult and urgent challenge today is that of creatively exploring new terrains of justice, where the prison no longer serves as our major anchor.” Today, Davis uses the phrase “the abolitionist imagination” to describe the mentality needed to see beyond how law enforcement works versus how it should. (She is currently collaborating with three other authors on a new book on the topic, tentatively titled “Abolition. Feminism. Now.”)

“The abolitionist imagination delinks us from that which is,” Davis tells me. “It allows us to imagine other ways of addressing issues of safety and security. Most of us have assumed in the past that when it comes to public safety, the police are the ones who are in charge. When it comes to issues of harm in the community, prisons are the answer. But what if we imagined different modes of addressing harm, different modes of addressing security and safety?”

Earlier this year, on March 23, Daniel Prude, a 41-year-old Black man with a history of mental-health issues, ran naked through the streets of Rochester, N.Y. He was subdued by several police officers, who placed a spit hood (a restraining mesh hood) over his head and held him down for two minutes until he stopped breathing. Prude was treated more like a criminal than a person in need of psychiatric care and would die a week after his encounter with police. Over these past months, I have thought often of Davis’s ideas on law enforcement, especially around issues involving the mentally ill. “What if we ask ourselves, ‘Why is it that whenever an issue arises in the community that involves, say, a person who is intellectually disabled or mentally challenged, the first impulse is to call an officer with a gun?’” she asks. “Why do we assume that the police are the ones who will be able to recreate order and safety for us? In those instances, there have been so many cases of people being killed by the police simply because of their mental health. This is especially the case with Black people.”

The New Haven-based artist Tajh Rust, 31, wanted his painting of Davis to be a “tribute to her decades of work.” Rust remembers seeing her in person for the first time as an undergraduate at Cooper Union in 2008 but being “too shy to thank her personally. I stood a few feet away from her while other students thanked her and posed for pictures with her.”

Tajh Rust’s “Angela Davis” (2020).

Photograph by Weichia Huang // New York Times

AS THE WORLD has caught up to her, Davis has found herself impressed with not just the fact of today’s current progressive organizations but also their leadership models — and in particular, how they have avoided the pitfalls of their predecessors: primarily, a cultish fixation on a charismatic male leader. Whether it was Huey P. Newton with the Black Panthers in Oakland or Mark Rudd with the Students for a Democratic Society at Columbia, most left-of-center organizations opposed to the American status quo in the ’60s suffered from some version of the Great Man syndrome, where women were either relegated to support roles or their contributions to the organizations were minimized. (I recently came across a vintage broadcast from 1973 of a 90-minute panel organized by PBS’s “Black Journal,” of which only two of the 12 panelists were women — Davis and the civil rights firebrand Fannie Lou Hamer — a composition inconceivable on any panel today.) “[Younger activists] know so much more than we did at their age,” she says. “They don’t take male supremacy for granted. One aspect of this shift in leadership models has to do with a critique of patriarchy and a critique of male supremacy.” She points to Black Lives Matter, the most influential U.S.-based protest movement in generations, which was founded by three Black women — Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi — all of whom have prevented a cult of personality developing around themselves. “Inevitably,” says Davis, “when one asks who is the leader of this movement, one imagines a charismatic male figure: the Martin Luther Kings, the Malcolm Xs, the Marcus Garveys. All of these men have made absolutely important contributions, but we can also work with other models of leadership that are rooted in our struggles of the past.”

As she reminds us, women have always been central to the history of American protest. She cites the 1955 to ’56 Montgomery bus boycott, which ignited the civil rights movement. Aside from Rosa Parks, whose arrest for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a bus in Montgomery, Ala., was the inciting action, the activist E.D. Nixon, former president of the local branch of the N.A.A.C.P., and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. are most often named as the boycott’s leaders. Yet “[the boycott] took place because Black women — domestic workers — had the collective imagination to believe that it was possible to change the world, and they were the ones who refused to ride the bus,” Davis says. “The collective leadership we see today dates back to the unacknowledged work of Rosa Parks and Ella Baker and many others, who did so much to create the basis for radical movements against racism.”

An Angela Davis-inspired poster is displayed above the entrance to the Seattle Police Department’s East Precinct, vacated June 8, 2020.

Jason Redmond/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images // New York Times

But the Montgomery bus boycott is not simply a historical reference for Davis. She grew up in Alabama, in nearby Birmingham, in a neighborhood called Dynamite Hill because of the racist bomb attacks on the homes of middle-class Black residents there. Two of the four young girls who were murdered in the 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing by members of the Ku Klux Klan lived near the Davis family home.

But the Davises were not intimidated. Her parents — Sallye, a schoolteacher, and Frank, a former teacher who owned a service station — made sure Angela, the eldest, her sister, Fania, and her brothers, Ben and Reggie, had a well-rounded childhood that included spending time on their uncle’s farm outside Birmingham and taking vacations up north in New York. Davis was a stellar student, regularly attended Sunday school and was active in the Girl Scouts. Crucial to her intellectual development was her mother’s participation with the Southern Negro Youth Congress; several of the organization’s leaders were members of the Communist Party. Formed in 1937 and highly active until 1949, the S.N.Y.C. boycotted businesses, registered Black voters and educated rural African-Americans about their legal rights long before the more celebrated work of the 1950s and ’60s civil rights movement. Though sanitized from many histories of the civil rights movement, the Communist Party supported the struggle against segregation from the 1930s until the Red Scare in the 1950s forced their participation underground. (It’s widely known, for example, that Bayard Rustin, a gay activist and former Communist, was a leading tactician of the 1963 March on Washington. What is less well remembered is how much the party supported the grass-roots organizing of the S.N.Y.C., along with many activist groups across the nation.)

Davis spent two of her high school years attending an integrated school in New York thanks to a Quaker-run program that placed promising Black Southerners in Northern schools. Upon graduating, she won a scholarship to Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., where she studied under the philosopher Herbert Marcuse, whose career as an intellectual and activist became a model for Davis. Marcuse belonged to the Frankfurt School, an ideology whose articulation of philosophy and critical theory would greatly influence much of Davis’s work. From 1965 to 1967, she studied in Europe, learning several languages, deepening her understanding of German philosophy and participating in rallies for the Socialist German Student Union. It was during these expatriate years that Davis began to see the racism she’d experienced growing up as a byproduct of an economy predicated on cheap, exploited labor, identifying institutional racism as a systemic problem long before the phrase came into vogue. She began to see herself not just as an academic but a participant in political change.

After returning to the United States in 1967, Davis affirmed her commitment to Communism, a key reason that she became associated with the Marxist-influenced Black Panthers. Because of her training and time spent abroad, Davis offered a more international vision as she attempted to build connections between oppressed groups, choosing not to separate the African-American struggle from that of other marginalized peoples, such as the Hmong, caught in the violence of the Vietnam War, and the battle against apartheid in South Africa. It’s why, in part, her arrest so resonated across the world. Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, as the Communist Party U.S.A.’s presence dwindled, and Communist regimes worldwide became increasingly totalitarian, Davis remained a staunch supporter of the party’s ideas, twice running as its candidate for vice president in the ’80s. In 1991, she stepped away, along with a number of other members, because the party refused to engage in processes of democratization; they formed a new organization, the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism. Today, she describes herself as a “small c” communist, remaining enthusiastic about the ideology but not beholden to any single organization.

NO MOVEMENT IS static. Contemporary Black activism has also largely been informed by the concurrent agitation surrounding trans and queer rights, both forces that have pushed back against the staunchly cis and heteronormative values that have dominated mainstream Black politics. It’s a shift that dovetails with Davis’s own biography. Though briefly married to a man in the early ’80s, Davis came out as a lesbian in 1997 and now openly lives with her partner, the academic Gina Dent. Her public announcement represented both a personal declaration and made more urgent her belief that racial and gender issues are deeply interconnected. “We didn’t include gender issues in [earlier] struggles,” she says. “There would have been no way to imagine that trans movements would effectively demonstrate to people that it is possible to effectively challenge what counts as normal in so many different areas of our lives.” She smiles. “A part of me is glad that we didn’t win the revolution we were fighting for back then, because there would still be male supremacy. There would still be hetero-patriarchy. There would be all of these things that we had not yet come to consciousness about.”

Davis at a Juneteenth rally and dockworker shutdown at the Port of Oakland, in Oakland, Calif., June 19, 2020.

Yalonda M. James/San Francisco Chronicle/Associated Press // New York Times

There’s a tendency to define racial progress in America by the upward mobility of various “minority groups” — to count and celebrate how many members have entered the middle class, have graduated from college or have multimillion-dollar deals with streaming services. Davis, however, finds those signifiers meaningless. Racism, she believes, will continue to exist as long as capitalism remains our secular religion. “The elephant in the room is always capitalism,” she says. “Even when we fail to have an explicit conversation about capitalism, it is the driving force of so much when we talk about racism. Capitalism has always been racial capitalism.” Davis cites the Covid-19 pandemic as “a crisis of global capitalism,” adding that “we do need free health care. We do need free education. Why is it that people pay fifty, sixty, seventy thousand dollars a year to study in a university? Housing: That’s something sort of just basic. At a time when we need access to these services more than ever before, the wealth of the world has shifted into the hands of a very small number of people.” She believes we need to imagine a “future that will allow us to begin to move beyond capitalism” but refuses to endorse any existing government as a model for the kind of America she envisions. It may be easy to be cynical about Communism and claim that America won the Cold War, but it’s also impossible to deny that this country’s financial system breeds income inequality, homelessness and divides us into warring camps separated by class, sex and race.

Because of this, many people were surprised by Davis’s support of Joe Biden’s campaign, but her reasoning is quite pragmatic: “We cannot allow Donald Trump to remain in power. The damage he’s done to the federal court system with his appointments will take several generations to correct.” Does she think the Democratic Party could be a vehicle for transforming America? “To be frank, no,” she says, but then adds, “I think it’s important to push the Democrats further to the left,” expressing great enthusiasm for the four progressive female congresswomen — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib — elected in 2018.

Here again, Davis is ultimately optimistic: this time about the future of progressive activism, viewing the current agitation in America as a continuation of the work that occurred during the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 and has grown over the last decade with the prominence of the Black Lives Matter movement. From her perspective, this is a moment many years in the making, based in grass-roots organizing that’s been happening outside the world of party politics and thus underrecognized by the mainstream media. It’s also the kind of organizing that doesn’t always bear fruit quickly. “When we do this work of organizing against racism, hetero-patriarchy, capitalism — organizing to change the world — there are no guarantees, to use Stuart Hall’s phrase, that our work will have an immediate effect,” she says. “But we have to do it as if it were possible.”

Angela Davis, photographed outside her home in Oakland, Calif., on July 25, 2020.

Photograph by John Edmonds // New York Times

She’s heartened, too, by the diversity of participants in Black Lives Matter marches and the willingness of white protesters to embrace the battle against white supremacy. “‘Structural racism,’ ‘white supremacy,’ all of these terms that have been used for decades in the ranks of our movements have now become a part of popular discourse,” she observes. “As we looked at the damage that the pandemic was doing, people began to realize the extent to which Black communities, brown communities and Indigenous communities were sustaining the effect of a pandemic in ways that pointed to the existence of structural racism. Then there was the fact that we were all sheltered in place; in a sense, we were compelled to be the witnesses of police lynching. That allowed people to make connections with the whole history of policing and the history of lynching and the extent to which slavery is still very much a part of the influences in our society today.”

AMERICANS ARE TERRIBLE at understanding history. We buy all too easily into the jingoism of Hollywood movies and our politicians’ pious platitudes. We possess an unjustified sense of self-regard. The effects of an inflated ego are pernicious; they stifle our ability to clearly see the world outside of ourselves, or our own role in it. Davis, though, has never accepted the myth of American exceptionalism. Rather, she has consistently argued that our triumphant narrative of Manifest Destiny is simply a cover for an exploitive financial system that corrupts our public life and represses our humanity.

These days, Davis uses social media to curate her own image. The photo at the top of her Facebook page is a favorite of mine. It was taken in Oakland on Juneteenth, June 19 of this year, as longshoremen along the West Coast shut down ports in support of Black Lives Matter. Davis, right fist held high, salutes (and is saluted by) a sea of young people. It is an image of defiance that connects labor organizing, activist politics and Black history. That Davis and the people around her are all wearing masks indelibly dates it to our present moment.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that our work as activists is always to prepare the next generation,” she says. “To create new terrains so that those who come after us will have a better opportunity to get up and engage in even more radical struggles. And I think we’re seeing this now.” She plans to be around to see it through.

[Nelson George is an American author, columnist, music and culture critic, journalist, and filmmaker. He has been nominated twice for the National Book Critics Circle Award.]

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21984560/George_Hutcheson___Lauren_Southern._Courtesy_The_Atlantic__1_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21984581/Mike_Cernovich._Courtesy_The_Atlantic.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21984586/Lauren_Southern___Gavin_McInnes._Courtesy_The_Atlantic.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21984608/674157310.jpg.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21984622/644207442.jpg.jpg)

Credit: David Clode, Unsplash

Credit: David Clode, Unsplash